Potential benefits

Easier specimen extraction

Easy conversion if cancer

Better cosmesis

Decreased pain

Better exposure for fascial closure

Potential drawbacks

Difficult learning curve

Instrument clashing

Possible increased rupture risk

Increased operative time (initial)

Table 10.2

Potential etiologies of adnexal masses

Benign etiologies |

Ovarian cysts |

Ovarian torsion |

Hemorrhagic cyst |

Theca lutein cyst |

Benign ovarian neoplasms |

Epithelial |

Germ cell |

Sex-cord/stromal |

Infectious/inflammatory |

Tubo-ovarian abscess |

Appendiceal abscess |

Diverticular abscess |

Endometrioma |

Fallopian tube lesions |

Hydrosalpinx |

Paratubal cyst |

Ectopic pregnancy |

Other masses |

Peritoneal inclusion cyst |

Leiomyomas |

Malignant etiologies |

Ovarian malignancy |

Epithelial carcinoma |

Germ cell tumors |

Sex cord/stromal tumors |

Sarcomas |

Fallopian tube carcinoma |

Low malignant potential tumors |

Metastatic lesions of adnexa |

Carcinomas |

Gastrointestinal |

Breast |

Pancreatic |

Pseudomyxoma/appendiceal tumors |

Sarcomas |

Table 10.3

SGO/ACOG guidelines for referral to a gynecologic oncologist

Postmenopausal | Premenopausal |

|---|---|

Elevated CA-125 | CA-125 >200 U/mLa |

Ascites | Ascites |

Nodular or fixed pelvic mass | – |

Evidence of metastasis | Evidence of metastasis |

Family history of one or more first-degree relatives with ovarian or breast cancer | Family history of one or more first-degree relatives with ovarian or breast cancer |

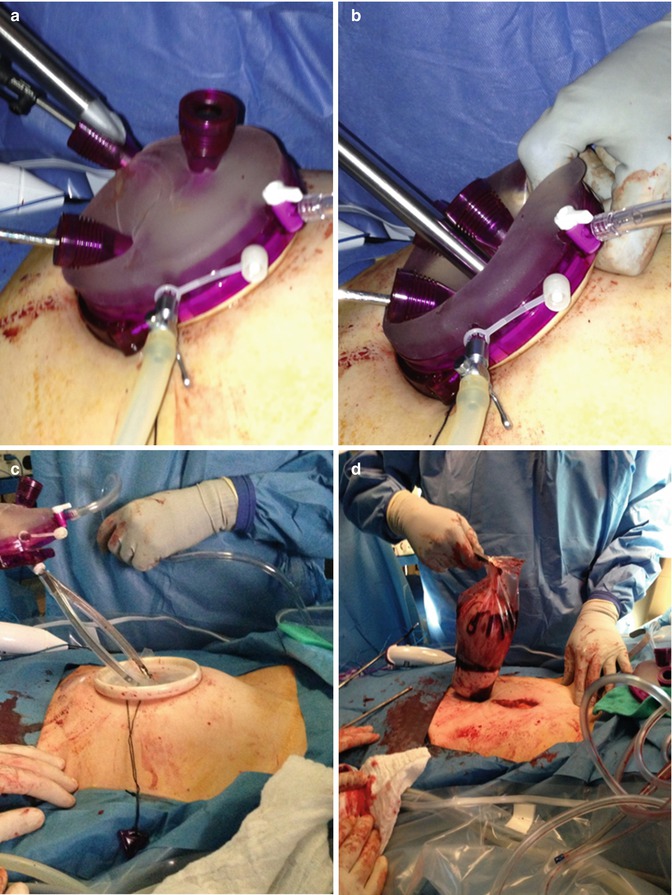

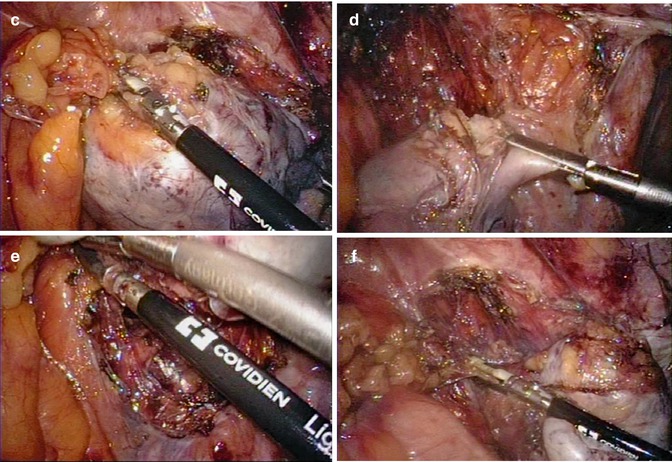

Fig. 10.1

Direct insertion of a large Endocatch bag through a Gel Point™ device (Applied Medical; Rancho Santa Margarita, CA). (a) The tip of the metal ring is advanced. (b) The bag is inserted directly through the gel. (c) Bag is cinched and metallic ring is withdrawn. (d) String is cut, gel cap removed, and specimen retrieved from the abdomen within the bag. Note that the incision in this case was extended to retrieve a very large, solid mass

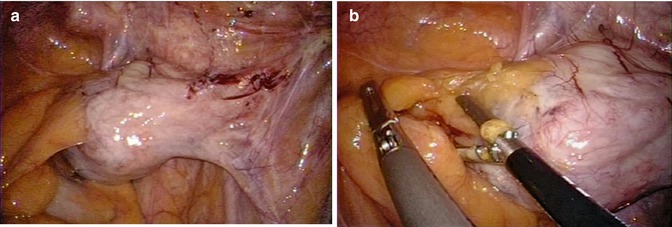

Fig. 10.2

Lysis of adhesions to expose adnexal mass using bowel grasper and endoscopic shears. (a) Lysis of filmy small bowel adhesions. (b) Cauterization of thick band and continued lysis of filmy adhesions. (c) Final lysis of small bowel adhesions. (d) Dissection of colon off of side wall to expose infundibulopelvic ligament

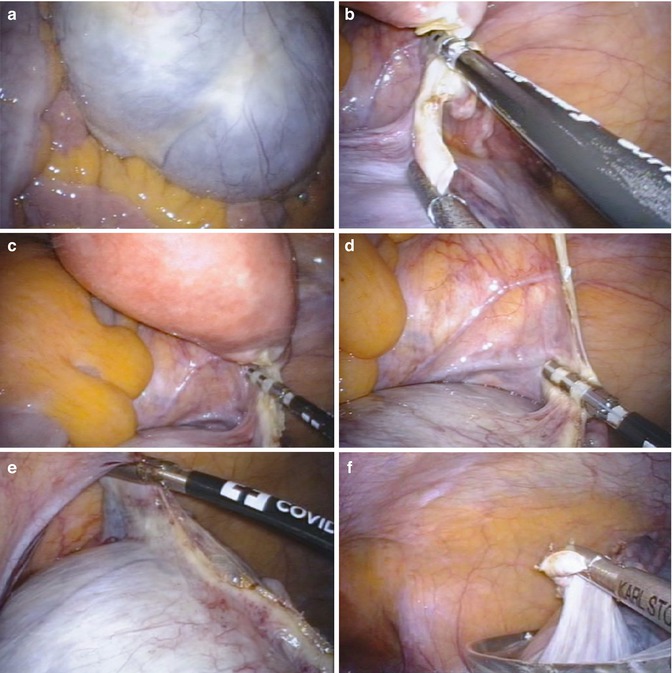

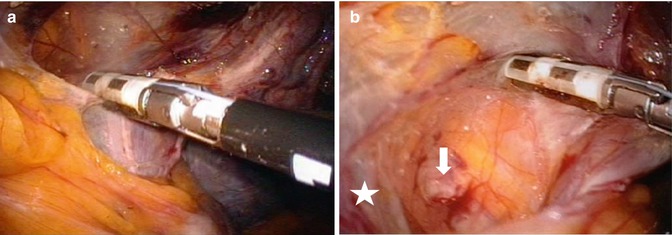

Fig. 10.3

Lysis of adhesions and excision of right ovarian fibroma. (a) Fibroma attached to sigmoid epiploica and side wall. Note ureter running posterior to anterior. (b) Lysis of epiploica adhesions. (c) Side wall open laterally and lower pole adhesions lysed. (d) Transection of infundibulopelvic ligament. (e) Mobilization away from the side wall. (f) Retrograde transection of inferior side wall attachments

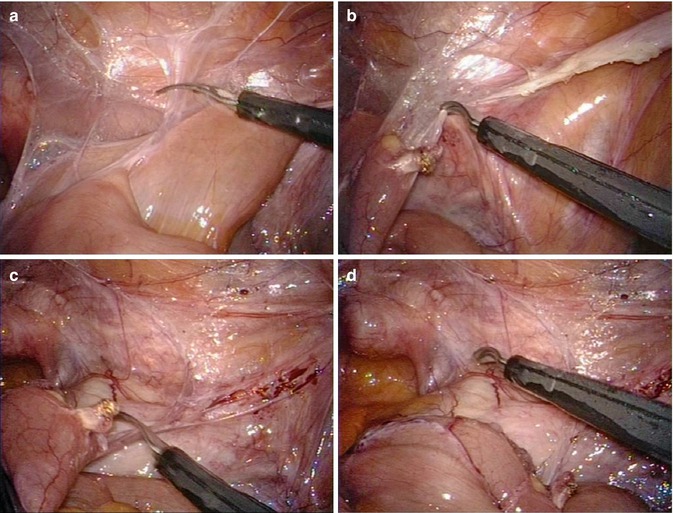

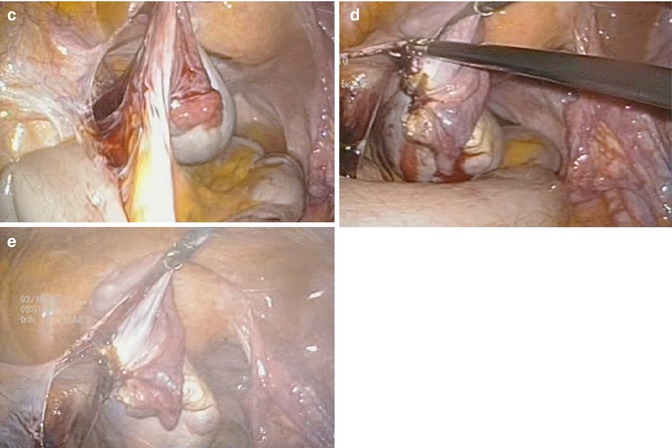

Fig. 10.4

Exposure of side wall and left salpingo-oophorectomy in patient with prior hysterectomy. (a) Opening of left pelvic side wall. (b) Exposure of iliac vessels (star) and ureter (arrow). (c) Traction on ovary to isolate infundibulopelvic ligament. (d) Transection of broad ligament. (e) Transection of distal side wall attachments

10.3 Procedure

The steps for single-port laparoscopic management of adnexal masses are listed in Table 10.4. Positioning is typically done as seen in Fig. 10.5. Most adnexal surgery is best performed via a transumbilical single-port approach. Entry into the peritoneal cavity should be carried out using the technique described by Hasson et al. [10]. Occasionally we have chosen an alternate site of entry, usually owing to a large uterus or a large adnexal mass, in which we make our incision in a supraumbilical location. Our preferred method of entry is to anesthetize the periumbilical region with bupivacaine. The edges of the umbilicus are grasped at 3 and 9 o’clock with Allis clamps, and we incise through the base of the umbilicus in the midline to make an incision measuring 1.5–2.5 cm. The fascial incision is extended, the peritoneum is grasped and entered, and a finger is swept into the peritoneal cavity to assess for adhesions. We then place an S-retractor into the peritoneal cavity at the inferior portion of the incision. The single-port system is then inserted into the peritoneal cavity and fixed in place, and the abdomen is insufflated. Once the camera is inserted into the peritoneal cavity, we use articulation of the flexible camera to evaluate the anterior abdominal wall around the port site and to evaluate the peritoneal cavity for ascites, carcinomatosis, and other pathology. The operative procedure itself can be carried out using standard, straight laparoscopic instruments (Fig. 10.6), but an increasing number of articulating instruments are available to decrease instrument clashing. The development of multifunctional instruments that enable us to dissect, seal vessels, and cut tissue without instrument exchanges has been a key to efficient single-port (and standard laparoscopic) procedures. Once the procedure is complete, we typically close the fascia with 0 delayed absorbable suture in a running fashion. If there was a previous umbilical hernia, we often use interrupted, figure-of-eight, nonabsorbable sutures. The skin is closed with a running subcuticular 4-0 absorbable suture.

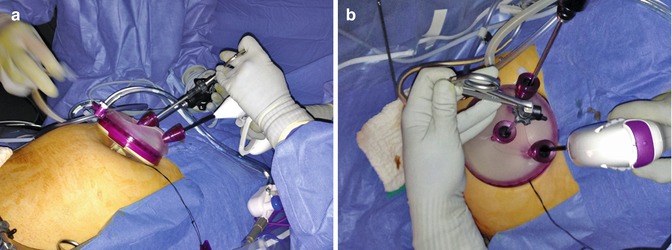

Fig. 10.5

Patient positioning. Typical positioning used with patient in lithotomy, both arms tucked and padded at sides, shoulders padded with a “beanbag” deflated to conform to the patient. The chest is taped/strapped with padding beneath. The beanbag can also be taped to the table if extra support is needed

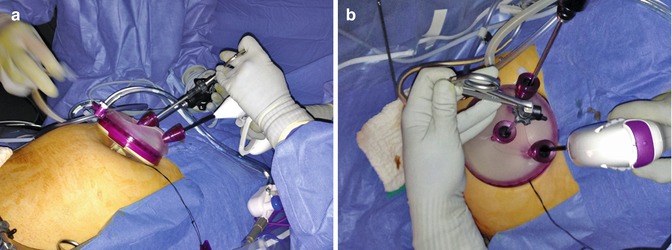

Fig. 10.6

Hand position in single-port laparoscopy with straight instruments. (a) Lateral view of hand positions. The nondominant hand (i.e., left) is toward the pelvis, with the handle of the instrument inverted. The dominant hand (i.e., right) is cephalad, with the instrument held in normal position. (b) Top view of hand positions. Note the port set-up of two ports cephalad and one caudad. The camera is in the right cephalad port

Table 10.4

Steps for single-port laparoscopic excision of an adnexal mass

Examination under anesthesia |

Umbilical/abdominal entry via Hasson technique |

Placement of single-port device and insufflation of abdomen |

Inspection of mass and peritoneal surfaces, including diaphragm (easier with 30° or flexible-tip laparoscope) |

Pelvic and abdominal washings |

Biopsy of sites suspicious for metastasis; get frozen section |

If malignant, convert to laparotomy for staging, if feasible; carry out laparoscopic staging, if it can be performed adequately; or discontinue laparoscopy and refer for staging |

If benign/no evidence of malignancy, proceed with single-port laparoscopy |

Cystectomy, oophorectomy, salpingectomy (excision of mass) |

Identify ureter |

Identify and ligate gonadal vessels for oophorectomy |

If prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, ensure all ovarian tissue is removed, including adhesions—typically 2–3 cm up infundibulopelvic ligament from ovary |

Place mass in laparoscopic specimen retrieval bag |

Open bag at abdominal wall and remove specimen for frozen section |

Inspect for hemostasis, irrigate, and close |

10.4 Single-Port Laparoscopic Adnexal Surgery in Gynecology

10.4.1 Tubal Sterilization

One of the first reports on the use of single-port laparoscopy was for tubal sterilization. Wheeless and Thompson [3] reported on 2,600 women who underwent tubal sterilization at Johns Hopkins between 1968 and 1972, via a one-incision periumbilical technique utilizing either one burn or three burns using electrocautery through an operative laparoscope with an eyepiece. This technique was compared to a two-incision technique for sterilization in an additional 1,000 patients. Of the total of 3,600 patients, there were 24 pregnancies following the sterilization procedure. Injury of the intestinal tract from electrocautery occurred in 11 women. Miller [11] described single-puncture sterilization in an office setting using a single-puncture laparoscope with intravenous conscious sedation and local anesthesia in over 1,100 women. Ismail et al. [12] described a single-puncture tubal sterilization technique using Filshie clips in 42 women. More recently, Sewta [13] published a report on single-port laparoscopic sterilization using fallopian tube rings in 2011 patients in India. There were no sterilization failures and no major complications.

10.4.2 Management of Ectopic Pregnancy

Bedaiwy et al. [14] described the management of 11 hemodynamically stable women with isthmic and ampullary ectopic pregnancies using laparoendoscopic single-site salpingectomy using a commercially available single-port device. In this study, the tubal mass measured 1–6.5 cm and fetal cardiac activity was present in 6 of the 11 patients. The median operative time was 35 min and blood loss was 30 mL. They reported no conversions and no intraoperative or postoperative complications. Yoon et al. [15] described their experience with 20 women with ectopic pregnancy treated by single-port salpingectomy using a homemade “glove port.” Outcomes in this series were similar, with no conversions in their series.

10.4.3 Management of Adnexal Masses

Increasing data have shown the utility of a variety of single-port laparoscopic techniques in the management of adnexal masses and other pathology (Table 10.5) [9, 16–25]. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) is an indication that appears favorable for laparoscopic management. Escobar et al. [16] described their initial experience with RRSO and found short operative times and no major complications in the RRSO group. Kim et al. [17] describe single-port access transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted adnexal surgery (SPATULAAS) for benign-appearing adnexal masses greater than 8 cm, using a homemade glove port. We have found that many adnexal masses up to 18 cm and some pedunculated leiomyomas with stalk width of ≤3 cm can be managed with a single port laparoscopic approach (Figs. 10.7 and 10.8).

Single-port access hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (SPA-HALS) was developed for the management of large adnexal tumors Rho et al. [9] compared 43 patients with large adnexal tumors managed by SPA-HALS with 96 patients managed by standard single-port laparoscopic surgery (SPL). Despite a larger median mass size in the SPA-HALS group (10.9 vs. 6.3 cm), they noted a significant reduction in tumor spillage (10.3 % vs. 31.3 %) and more frequent adnexa-conserving procedures (76.7 % vs. 43.8 %) in the SPA-HALS group, compared with the standard SPL group.

Isobaric single-port laparoscopy has also been described using an abdominal wall elevator with a subcutaneous surgical wire or “rope” and steep Trendelenburg to visualize the pelvis without the use of pneumoperitoneum. This technique has been used for a variety of procedures on the ovaries and in the management of ectopic pregnancy [26–28]. The number of applications for single-port laparoscopy in the management of adnexal pathology continues to grow and will only be limited by the gynecologist’s imagination and skill set.

Although culdoscopy enjoyed popularity in the 1950s and 1960s, its use is more limited today. However, there are still papers published detailing transvaginal management of a variety of adnexal and uterine pathology. Tsin and colleagues [29] described a variety of surgical procedures performed via transvaginal laparoscopy, including ovarian cystectomy, oophorectomy, myomectomy, appendectomy, and cholecystectomy. There were no major complications in their series, but reported bowel injury rates for a transvaginal approach have ranged from 0.25 to 0.65 % [30]. In their retrospective review, 22 of 24 injuries resolved with conservative management consisting of hospital observation and antibiotics.