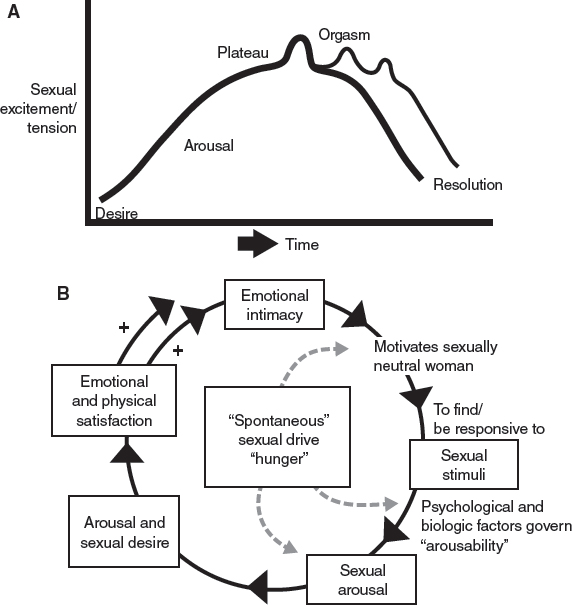

CHAPTER 17 Many individuals who identify on the range of gender nonconforming face a variety of critical issues both before and after gender reassignment surgeries, including gender affirmation surgery (GAS), also known as sex reassignment surgery, bottom surgery, or lower surgery. Frequently these issues are in relation to sexual health. For many, GAS alleviates body dysmorphia, because the decision to pursue GAS is closely tied to the ability to function sexually as the gender with which one identifies. Accordingly, postoperative sexual satisfaction often depends on the functional ability of the newly created genitalia. Even when sexual function is not the driving factor for a person to undergo GAS, sexual health contributes to overall mental health and relationship satisfaction, underscoring the importance of sexual function throughout the transition, but particularly after GAS.1–4 With advancing techniques for GAS, preserving patients’ sexual function has become a priority for surgeons. Still, long-term sexual and physical rehabilitation is crucial to maintaining and improving sexual function of the new genitals,5 although optimizing the sexual experience for transgender individuals does not simply start after surgery. Rather, it is a long-term process that occurs throughout the transition. Lifelong transgender health care by a team of providers, including mental health professionals, is very important. Often transgender individuals feel they are “done” with counseling after completing marker events such as GAS, and frequently counselors and gender specialists are seen as “gatekeepers,” necessary only for letter writing. However, mental health professionals are an integral component of the transgender person’s lifelong health care team, and those with expertise in sexual health—gender specialists/sexologists/sex therapists—are crucial for the individual to achieve optimal sexual function and satisfaction. However, sexual health should not be left entirely to the specialist. All members of the health care team should evaluate and address sexual issues with transgender patients if they manage them for other aspects of the transition. Both cross-sex hormone therapy and GAS have significant impacts on sexual function and satisfaction.1 Providers should address these considerations before they initiate treatment or perform surgery. Any member of the transgender individual’s care team can perform the initial evaluation of sexual health. Appropriate referrals to qualified mental health or sexual health practitioners should be made as necessary. When facilitating sexual health concerns for transgender individuals, an initial evaluation should include questions related to their sexuality.6 Questions that may be incorporated into the history-taking are shown in Box 17-1. It is critical to have referral resources for any concerns that are identified. Assessing sexual health, including desire, arousal, orgasm, and sexual satisfaction, can be evaluated objectively by any member of the transgender individual’s care team. Baseline sexual function, particularly arousal and orgasmic capability, should be assessed before surgical intervention that alters reproductive organs or genitalia. The goal of any surgery to the internal or external genitalia is to preserve this functionality. If a patient lacks orgasmic capability or has other sexual dysfunction, the provider should refer the individual to the appropriate practitioners, who can determine and treat the cause of the problem. Because GAS alleviates gender dysphoria,7 it may be therapeutic for sexual dysfunction if it is caused by the distress of having gender incongruent genitalia. However, if the dysfunction is mechanical, hormonal, or caused by other underlying psychological factors, these must be addressed before surgery, because surgery cannot restore function. Persons who have orgasmic capability before GAS can typically orgasm afterward. Therefore, any challenges with orgasm must be addressed before surgery, because surgery cannot restore function or by itself heal psychological wounds. This can also be a point of reassurance for patients, who may be concerned about losing their ability to orgasm. Box 17-1 History Questions for Initial Sexual Health Evaluation Sexual dysfunction is typically categorized into four domains: desire, arousal, orgasm, and pain.8 Objective, validated questionnaires to assess each of these categories can be beneficial for initial screening of sexual function. A multitude of inventories for evaluating sexual dysfunction exist,9 and the appropriate choice should be made based on feasibility and usefulness. Some tools such as the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) are designed to briefly assess the core domains of sexual dysfunction,10 whereas others such as the Derogatis Interview for Sexual Functioning (DISF) can be used to evaluate sexual cognition and fantasy, sexual behavior and experience, and relationships, along with the standard functional domains.11 When selecting a tool, one must remember that these have largely been designed to assess cisgender—those whose gender identity is congruent with their assigned gender—sexual functioning and may contain questions that are not applicable to transgender individuals. Therefore questions should be screened before they are used with transgender patients. Objective evaluations should be used only as screening tools and as a starting point for conversation and counseling between the provider and patient. Sexual health can be difficult for individuals to discuss, underscoring the importance of the provider to create a comfortable environment to facilitate conversation and refer the patient to the appropriate sexual health expert or therapist. In addition to sexual health concerns related to function and satisfaction that can arise in any individual, unique issues may present in transgender persons. These include gender dysphoria in a sexual relationship, changes in sexual attraction, fantasy, orientation, or preferences as part of gender transition, as well as the impact of hormone therapy and surgery on the domains of sexual function.6 Although hormone therapy and GAS are generally associated with improved quality of life, sexual satisfaction, and sexual function,1,7 these outcomes may take time to achieve as the person learns to adjust to a new body. Transgender individuals vary in their comfort and willingness to discuss their sexual health. For some, speaking about their genitals, even with sexual partners, causes great discomfort.12 This may stem from distress caused by having gender-incongruent genitalia or because the patient has difficulty finding appropriate terms to describe certain body parts.6 This distress may arise from past sexual scripting, or surprisingly, the initial conflict between gender identity and the new experience of naming and owning newly made genitals. It is often assumed that because transgender individuals need to undergo examinations and surgeries that necessitate private and probing questions, they are open and comfortable with conversations or questions about their genitals. Each provider must take the time to really see and affirm individuals’ hearts, not parts. The distress that a patient may associate with discussing genitalia may also be present if the genitalia are touched, and like cisgender people, male-to-female and female-to-male individuals engage in a wide range of sexual activities. So the provider cannot make assumptions about the types of sexual activities in which patients’ engage.6 Despite the complexities of transgender sexual health, the entire team of providers should invest in ensuring that it is optimized for each patient. Transgender individuals are more likely to engage in behaviors that put them at increased risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections, causing higher prevalence of these infections in transgender populations.6,13,14 These high-risk behaviors and resultant infections have been linked to gender dysphoria and the challenges associated with affirming one’s gender identity.15,16 Promoting a positive attitude toward sexual health and enhancing sexual function are associated with greater selfefficacy in making safer sex choices, underscoring the importance of sexual health in the overall well-being of transgender individuals.12,17 Improving sexual health may necessitate referral to a mental health professional with expertise in sexual counseling or to a medical provider who can address other underlying causes of sexual dysfunction. Before GAS, the surgeon must counsel patients regarding their sexual expectations after the procedure. This should include a discussion about the types of sexual activities, including intercourse, they may have and what implications surgery may have on these. For example, a transgender woman with a female partner may not have the same sexual goals as one with a male partner. Any transgender patient needs to be encouraged like any cisgender individual about the possibilities of outer/inner stimulation, which also could include any accoutrements/aids that may enhance stimulation, arousal, and orgasm. As part of the preoperative consultation, the surgeon should also determine how the person is currently achieving sexual satisfaction, because this may provide insight into how to appropriately counsel the patient for optimal postoperative sexual function. Familiarity with common strategies and devices transgender individuals often use for sexual activity can also aid in conducting this conversation more comfortably for both physician and patient. For example, transgender men often use “packers” to give the outward appearance of a bulge through their clothing. This is referred to as “soft packing,” because it mimics a flaccid penis. However, these generally cannot be used for sex. In recent years “dual-use” packers have been developed that can be used for both daily appearance and sex but can often be uncomfortable and unrealistic. In addition, the internal malleable rod can potentially injure a sexual partner. Hard packers are dildos or similar prosthetics that are permanently erect for sexual penetration.18 Alternatively, transmen may not engage at all in penetrative intercourse. Transmen may also use “stand-to-pee” devices (STPs) to be able to urinate in the standing position, which can be of particular importance for assimilating in public bathrooms. Some STP devices can be fashioned at home with a coffee can or other flexible plastic disk, a medicine spoon, or the upper portion of a plastic soda bottle. Some people choose to purchase specially crafted STPs that they carry with them, and others wear a soft packer with STP functionality. Conversely, before GAS, transwomen frequently tuck their penises, which may cause their genitalia to appear distorted on physical examination. Tucking may also not adequately conceal their genitalia, particularly the scrotum, when wearing a bathing suit or other diminutive apparel. Before removal of the testes, spontaneous erections are also quite common, which may further add to distress. If GAS is not desired or is prohibited by cost or other factors, transwomen may be counseled to have just an orchiectomy to prevent these occurrences that may contribute to their dysphoria or interfere with sexual relationships. Although the conversation about sexual function should begin before GAS, it should be revisited with frequency in the postoperative period. In general, reports of sexual function after GAS, including the ability to orgasm, are positive.1,19,20 Having genitalia congruent with one’s gender identity and the ability to perform sexually in that capacity contribute greatly to this postoperative sexual satisfaction. However, as many transgender persons point out, attaining optimal sexual function takes time.21 The surgeon can help in this process by making sexual counseling a component of every postoperative visit. At their first postoperative appointment, which is typically 5 to 10 days after surgery, MTF patients should receive training with vaginal dilators. The patient should be encouraged to self-dilate in the office to ensure proper technique and overcome any apprehension that may exist. After this initial visit, the well-healing patient should be encouraged to dilate at home on a daily basis. Concern for wound dehiscence or tissue necrosis may necessitate a longer waiting period before self-dilation can begin. If the patient plans to engage in receptive penetrative intercourse, she can generally start having sex 6 weeks after surgery. She should still self-dilate for an extensive period; some surgeons recommend continuing at least 6 months to ensure patency of the vaginal canal.22 The amount of self-dilation can gradually be decreased as the frequency of intercourse increases over time. The transgender woman who partners with women and/or does not engage in receptive intercourse may require the use of vaginal dilators for a longer period to maintain a patent neovaginal canal. The risk of damaging the neovaginal construction with overly aggressive dilation also exists,23 and thus the patient should be advised to dilate carefully. Vaginal lubrication may be a concern for MTF patients, because the neovagina does not have the same secretory capacity as the natal vagina, particularly when constructed from penile and scrotal tissue. However, studies have shown that many transgender women experience fluid release with sexual stimulation,19,24 even retaining ejaculatory capacity in some cases.24,25 It is thought that this fluid is produced in the Cowper’s glands, but these glands can atrophy with long-term cross-sex hormone therapy. Presently the composition and origin of this fluid have not been established with certainty.1 Accordingly, most patients will likely require lubricant use for intercourse. If this is a major concern before surgery, the patient may be advised to consider a sigmoid colon vaginoplasty. Because of the endogenous mucous production in this tissue, fewer patients reported complaints of inadequate lubrication.22 For MTF patients, surgical outcomes that can affect sexual function include stenosis or stricture of the neovaginal canal, inadequate vaginal depth, and vaginal prolapse.22,26,27 Stenosis can occur if patency of the neovagina is not maintained with frequent dilation or penetrative intercourse. These complications may require surgical revision, which typically resolves any dyspareunia.22 If the patient has not undergone permanent genital hair removal before surgery, vaginal hair growth may occur, particularly if a large scrotal graft is used.26 This can be sexually disruptive. If permanent depilation is cost prohibitive, the surgeon can electrocauterize the hair follicles of the skin graft before insertion in the neovaginal canal. FTM patients typically require longer recovery periods than MTF patients, which may necessitate a longer waiting period before initiating sexual activity, particularly if patients have had a multistaged procedure. Depending on the type of phalloplasty, tactile and erogenous sensation may not be immediately present in the neophallus. Patients who undergo radial forearm phalloplasty or other free flap procedure may require up to 1 year to regain tactile sensation to the tip of the phallus. Erogenous sensation may return sooner.28 This disparity in sensation can put the patient at risk of damaging the neophallus if he wishes to engage in sexual activity but does not yet have tactile sensation. If the patient has an osteocutaneous flap, sexual intercourse may cause the bone to extrude inadvertently. For patients without osteocutaneous flaps who are awaiting implant placement, which is typically not done until tactile sensation is regained, the barrier to intercourse may be erectile capability. Transgender men have been known to wrap Coban (3M, St. Paul, MN) around the neophallus and cover it with one or two condoms in order to achieve the rigidity required for penetration.21 For both MTF and FTM patients, familiarizing themselves with their new anatomy is imperative to achieving sexual gratification. Although the surgeon should encourage patients to explore new genitalia independently or with a partner, describing the location of erogenous and/or erectile tissue can be helpful. Most erogenous sensation for transgender females is derived from the neoclitoris, which is a glans penis flap with a preserved neurovascular bundle. The patient can be encouraged to autostimulate or have a partner stimulate the neoclitoris to achieve orgasm. MTF patients can also experience sexual arousal from the neovagina if it has been constructed with penile or scrotal skin. The prostate is also left at least partially intact and can be stimulated by neovaginal penetration.26 For a transgender man who has undergone phalloplasty, erogenous sensation will primarily be from the clitoris that has been buried at the base of the phallus.28 He should be counseled that his orgasm may depend on penetrative intercourse or stimulation that allows pressure in that region. Additional erogenous sensation may be derived from stimulation of the phallus itself if the dorsal nerve of the clitoris is anastomosed with one of the nerves in the neophallus flap. Surgeons may vary in their techniques for nerve anastomoses and positioning of the clitoris. They must also discuss these surgical plans with the patient as part of preoperative and postoperative counseling. Both MTF and FTM persons can experience a change in orgasmic quality after GAS. FTM individuals report more powerful, forceful orgasms, whereas MTF patients report more intense, smoother, and longer orgasms.19,29 After GAS sexual function and satisfaction in both MTF and FTM individuals are variable, making the impact of surgery on sexual health a challenge to predict.1 Certainly given the many other factors that contribute to sexual health in the transgender person, dysfunction after surgery cannot be completely attributed to the surgery alone and may only be transient. The following concerns are commonly experienced and expressed by “the real experts”—transgender individuals—in their unique journeys needing continued “dream team” support after gender affirmation surgeries. Even before surgery, body image can be a challenge for transgender individuals. Societal expectations and depictions of masculinity and femininity and cultural norms related to attractiveness may cause transgender persons to have difficulty accepting their bodies.6 Surgery, whether GAS or other procedures such as chest reconstruction/breast augmentation, may alleviate gender dysphoria but may not completely improve a transgender person’s body image. Accordingly, many transgender individuals pursue cosmetic procedures, even to an obsessive level, to relieve generalized discomfort with their bodies. For example, transgender men can develop a preoccupation with synthol—an oil that is injected directly into the muscle to provide bulk—to enhance their upper bodies, and transgender women can seek multiple facial feminization procedures. Frequently these obsessions will develop as compensation for genital dysphoria. Providers should consider screening patients for body dysmorphic disorder and referring them for appropriate mental health treatment if this is a concern. Surgery may not alleviate all body image concerns and may even bring about new ones.6 The following are some issues with which transgender individuals may be faced: It is very important that the new bodied transperson take time to shift from the initial dysphoria through each step of “what I expected versus what I now experience/see” in the mirror versus “what others may perceive/experience with my new body.” This process impacts healthy body image versus fantasy body image. GAS for both MTF and FTM individuals results in high satisfaction and little regret.7,30 However, many transgender individuals go through a transient period of grief or loss after GAS. This can be caused by feelings of sadness that accompany the realization that certain aspects of gender are not achievable, even with surgery. Conversely, they may mourn the loss of reproductive organs or feel temporary regret immediately after surgery that may be provoked by postoperative pain or complications.6,30,31 This grief is generally self-resolving but may require therapeutic intervention. The following are some questions that transgender individuals may face after surgery: Recognizing, acknowledging, grieving, affirming, and celebrating the unique transgender experience means that the transgender individual will never be exactly like cisgender individuals. The transgender individual, even with body parts that now align with gender identity, contributes insights and perspective that no cisgender individual can truly understand. Continued support from peers is often needed and valued through social media, local support groups, and trans conferences. Being a role model for others on educational panels is a win-win for self and other medical, mental health, religious, or education students. Appropriate pronoun usage can be an important component of a person’s gender affirmnation. Establishing and using the person’s preferred pronoun is also a crucial aspect of transgender-sensitive care. However, some individuals may find that they grapple with their preferred pronoun after surgery. Some of their concerns include: Letting family, friends, and work peers/employers know the preferred name/pronoun is important, and those who are the closest and have had the longest history with the trans individual usually need time and “brain rebooting.” Again, support from mental health professionals and peers can help some individuals in this lifelong struggle. Some people choose to live their lives as openly trans, whereas others opt to live stealth; they prefer to pass as their identified gender and do not disclose that they are transgender. Some choose to live stealth as a matter of safety or privacy, whereas others choose this option simply because it makes them happy, or it facilitates dating and intimate experiences without disclosure. Many live in a manner that is a combination of stealth and open.33 After a patient undergoes GAS, considerations regarding the decision to live in a certain manner can arise: There are many ways to be supportive and educate. Some disown their past—some sit “shiva” for their biologic birth to “rebirth” state. Some transgender individuals mark their biologic birthday and others celebrate their surgical birthday. Each transgender individual has a right to decide when, how, how much to disclose and hopefully not be outed by those who do not recognize personal disclosure and privacy. A counselor or educator can help reinforce this personal decision and help trans individuals with disclosure process. Transitioning, especially GAS, can affect a person’s current relationship or the ability to enter into a new relationship. Some trans individuals find that it is easier to begin and maintain a relationship after surgery, whereas others find it more challenging.34,35 As the transition progresses, transgender persons may find their sexual orientation changing, which may complicate or confuse relationships or dating.30,36 They may also find existing relationships, even marriages, challenging. For instance, after GAS only a small percentage of individuals live with their spouse after surgical transition.7,30,37 Other challenges that specifically arise after surgery may be regarding functionality of new genitalia and how to negotiate them in new or preexisting sexual relationships. Concerns about the transgender person in regard to relationships or dating include: Sex therapy with transgender individuals can often follow the same process as with any person who has experienced body changes and wishes to see what is possible in body connection/sexual arousal and functioning. Sex therapy includes assessment of any other physical, psychological, and pharmaceutical variables that can contribute to the transgender individual’s and their partner’s unique sexual desire, arousal, and functioning. The sex therapy process often includes the following: This step-by-step process allows transgender individuals safety and comfort in discovering how their postoperative body responds in arousal and sexual functioning. This process could include manual, oral, and intercourse experiences and is directed by a trained sex therapist/gender specialist/sexologist who facilitates the sex therapy process by verbally inviting the couple to practice in the privacy of their home and returning to evaluate each step. If the transgender patient does not have a partner, a trained sexual surrogate is often used in the same step-by-step manner supervised by the sexologist. Although many sexologists use a three-stage or four-stage sex response model with a starting (desire/arousal), middle (plateau), and ending point (orgasm/ejaculation/resolution) (Fig. 17-1, A), Basson’s nonlinear model is often more realistic for many transgender and cisgender individuals38 (Fig. 17-1, B).

Sexual Health After Surgery for Transgender Individuals

Key Points

Any member of the transgender individual’s care team, including any physician managing an aspect of transition that can affect sexual function such as hormone therapy or gender affirmation surgery, can evaluate sexual health. Appropriate referrals to qualified mental health or sexual health practitioners should be made as necessary.

Any member of the transgender individual’s care team, including any physician managing an aspect of transition that can affect sexual function such as hormone therapy or gender affirmation surgery, can evaluate sexual health. Appropriate referrals to qualified mental health or sexual health practitioners should be made as necessary.

Sexual dysfunction can be categorized into four domains: desire, arousal, orgasm, and pain. Objective, validated questionnaires to assess each of these categories can be beneficial for initial screening of sexual function.

Sexual dysfunction can be categorized into four domains: desire, arousal, orgasm, and pain. Objective, validated questionnaires to assess each of these categories can be beneficial for initial screening of sexual function.

Before gender affirmation surgery, the surgeon should counsel patients about what could be expected sexually after the procedure.

Before gender affirmation surgery, the surgeon should counsel patients about what could be expected sexually after the procedure.

Surgery may not alleviate all body image concerns and may even bring about new concerns such as coping with keloiding/scarring.

Surgery may not alleviate all body image concerns and may even bring about new concerns such as coping with keloiding/scarring.

Transitioning, especially gender affirmation surgery, can affect a person’s current relationship or ability to enter into a new relationship. Some trans individuals find that it is easier to begin and maintain a relationship after surgery, whereas others find it more challenging.

Transitioning, especially gender affirmation surgery, can affect a person’s current relationship or ability to enter into a new relationship. Some trans individuals find that it is easier to begin and maintain a relationship after surgery, whereas others find it more challenging.

Sex and intimacy therapy can be beneficial after gender affirmation surgery to cope with new body parts as well as postsurgical developmental stages and exploring sexuality and intimacy issues.

Sex and intimacy therapy can be beneficial after gender affirmation surgery to cope with new body parts as well as postsurgical developmental stages and exploring sexuality and intimacy issues.

Sexual Health Evaluation

History

Objective Evaluations of Sexual Health

Many transgender individuals identify with different names/words/pronouns. Please tell me about your preferences.

Many transgender individuals identify with different names/words/pronouns. Please tell me about your preferences.

Many people experience a variety of relationships. How do you identify in terms of your orientation?

Many people experience a variety of relationships. How do you identify in terms of your orientation?

Please describe your dating, sexual, romantic experiences, and relationships, including social media—past and current, if any—and how you felt/feel about these relationships?

Please describe your dating, sexual, romantic experiences, and relationships, including social media—past and current, if any—and how you felt/feel about these relationships?

Please describe your sexual activities, including masturbation and with a partner or partners, past and current, if any. How did/do you feel about your sexual functioning by yourself or with other(s)?

Please describe your sexual activities, including masturbation and with a partner or partners, past and current, if any. How did/do you feel about your sexual functioning by yourself or with other(s)?

Does your body image/function affect your dating or sexual activities? If so, in what way(s) does it affect it?

Does your body image/function affect your dating or sexual activities? If so, in what way(s) does it affect it?

How do you hope gender affirmation surgery will affect your body image, masturbation, dating, relationships, and sexual activity?

How do you hope gender affirmation surgery will affect your body image, masturbation, dating, relationships, and sexual activity?

What are some of your concerns about gender affirmation surgery regarding your sexual desire, arousal, or sexual functioning?

What are some of your concerns about gender affirmation surgery regarding your sexual desire, arousal, or sexual functioning?

Do you have concerns about sexually transmitted infections/pregnancy or sexual abuse issues?

Do you have concerns about sexually transmitted infections/pregnancy or sexual abuse issues?

Transgender Sexual Health Concerns

Sexual Health and Gender Affirmation Surgery

Preoperative Considerations

Sex After Gender Affirmation Surgery

Other Postoperative Considerations

New Body Image

Does my new body look and respond in the way I imagined/fantasized about?

Does my new body look and respond in the way I imagined/fantasized about?

Will scarring/keloiding affect my total comfort around others (for example, shirtless/in sexual situations)?

Will scarring/keloiding affect my total comfort around others (for example, shirtless/in sexual situations)?

Will I struggle with “half-body” identity in this process if I cannot afford to continue surgeries?

Will I struggle with “half-body” identity in this process if I cannot afford to continue surgeries?

Gender Identity and Labels

Does having newly constructed genitals mean I am now like a cisgender male or female, or do I/will I identify as transman/transwoman, pangender, androgyny, boi, demigirl/demiguy, femme, gender gifted, gender nonconforming, gender fluid, agender, genderqueer, gender/sexual minorities, intersexual, intergender, neutrois (feeling one does not have a gender), nonbinary, postop, third gender, transfeminine/transmasculine, two spirited, or any other of the myriad of identities that celebrate the range of experiences?32

Does having newly constructed genitals mean I am now like a cisgender male or female, or do I/will I identify as transman/transwoman, pangender, androgyny, boi, demigirl/demiguy, femme, gender gifted, gender nonconforming, gender fluid, agender, genderqueer, gender/sexual minorities, intersexual, intergender, neutrois (feeling one does not have a gender), nonbinary, postop, third gender, transfeminine/transmasculine, two spirited, or any other of the myriad of identities that celebrate the range of experiences?32

Do I miss my original genitals or certain aspects of their functions?

Do I miss my original genitals or certain aspects of their functions?

Even after surgery, am I still upset that I lack certain sexual/reproductive abilities?

Even after surgery, am I still upset that I lack certain sexual/reproductive abilities?

Will others in the cisgender or gay/bi/lesbian community affirm my identity?

Will others in the cisgender or gay/bi/lesbian community affirm my identity?

Will cisgender individuals want to date me and be intimate?

Will cisgender individuals want to date me and be intimate?

Do I have to date only transgender individuals?

Do I have to date only transgender individuals?

Preferred Pronouns

Do I identify with he, she, him, her, hers, his, or they, ze, ey, or any other or no pronouns?

Do I identify with he, she, him, her, hers, his, or they, ze, ey, or any other or no pronouns?

Why can’t family, friends, work peers/employers use my preferred name/pronouns, even after surgeries and name change?

Why can’t family, friends, work peers/employers use my preferred name/pronouns, even after surgeries and name change?

Active Versus Stealth

Does surgery affect how I want to be seen … or not seen?

Does surgery affect how I want to be seen … or not seen?

Would my transgender peers feel I am being disloyal or politically incorrect if I choose to be stealth (living the gender identified/surgery confirmed life but not “out” as trans)?

Would my transgender peers feel I am being disloyal or politically incorrect if I choose to be stealth (living the gender identified/surgery confirmed life but not “out” as trans)?

Dating, Mating, and Relationships

If I am coupled or married, how does my partner (or partners) respond to my new surgeries? How will it have an impact on our affection, social, emotional, intellectual, physical, spiritual, aesthetic, and sexual intimacies?

If I am coupled or married, how does my partner (or partners) respond to my new surgeries? How will it have an impact on our affection, social, emotional, intellectual, physical, spiritual, aesthetic, and sexual intimacies?

How do dating sites accept transgender individuals? When and how do I disclose?

How do dating sites accept transgender individuals? When and how do I disclose?

Would someone want to date me even with a body that now matches my gender identity?

Would someone want to date me even with a body that now matches my gender identity?

How would I find out how my “virgin” genitals work in a safe and supportive experience?

How would I find out how my “virgin” genitals work in a safe and supportive experience?

Sex Therapy With Transgender Individuals

Body image: Because transgender individuals often avoid looking at their breasts or genitals before transition surgeries, encouraging visual awareness and validation of the total body can be an important component of the therapeutic process both before and after surgery.

Body image: Because transgender individuals often avoid looking at their breasts or genitals before transition surgeries, encouraging visual awareness and validation of the total body can be an important component of the therapeutic process both before and after surgery.

Body mapping: This technique allows the individual to identify step-by-step feelings about a variety of touches on each body part and “storyboard” how one would like to be touched or imagines being touched. Haloing the body (close body contact but not direct touching/sharing energy/care/concern/love) can be included for trust building, especially if one has been physically, emotionally, or sexually abused.

Body mapping: This technique allows the individual to identify step-by-step feelings about a variety of touches on each body part and “storyboard” how one would like to be touched or imagines being touched. Haloing the body (close body contact but not direct touching/sharing energy/care/concern/love) can be included for trust building, especially if one has been physically, emotionally, or sexually abused.

Eye gaze: This technique is used to invite the soul/spirit. It can also be expanded to include body gaze.

Eye gaze: This technique is used to invite the soul/spirit. It can also be expanded to include body gaze.

Holding/breath connection: This exercise builds trust through somatic/breath imprinting, holding, snuggling, cuddling, breathing, and connecting.

Holding/breath connection: This exercise builds trust through somatic/breath imprinting, holding, snuggling, cuddling, breathing, and connecting.

Sensate focus exercises: These are step-by-step touch exercises that are at first not genitally focused that ultimately progress to total body connection, which includes the genitals. These exercises can include touching that is observational, nurturing, playful, sensuous, and sexual. Evaluation after each exercise includes reviewing what was positive and comfortable or challenging, uncomfortable, painful for each person, and any requests or specific questions for the partner.

Sensate focus exercises: These are step-by-step touch exercises that are at first not genitally focused that ultimately progress to total body connection, which includes the genitals. These exercises can include touching that is observational, nurturing, playful, sensuous, and sexual. Evaluation after each exercise includes reviewing what was positive and comfortable or challenging, uncomfortable, painful for each person, and any requests or specific questions for the partner.

Abdominal Key

Fastest Abdominal Insight Engine