A

One (or more) mucosal break< 5 mm that does not extend between the peaks of two mucosal folds

B

One (or more) mucosal break> 5 mm long without continuity between the peaks of two mucosal folds

C

One (or more) mucosal break continuous between the peaks of two or more mucosal folds but involving less than 75 % of the circumference

D

Mucosal breaks involving at least 75 % of the esophageal circumference

Grades A and B are the most common and, compared to C and D, have an increased response to proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) (as high as 90 %). On the other hand, the most severe grades only heal in 50 % of the cases [13], have a higher tendency to relapse when medications are withdrawn, and have a fourfold increased risk at 2 years of developing Barrett’s esophagus (BE), with respect to A and B grades [14,15].

There is only a weak correlation between degree of damage, esophagitis grade, and symptoms severity; however, there seems to be a link between erosive esophagitis and contact time with acidic juice.

Symptoms

Typical symptoms of GERD are heartburn and regurgitation. Other common symptoms are dysphagia, epigastric pain, bloating, belching, and nausea.

Symptoms are typically worsened by heavy meals, after the ingestion of certain foods, especially fatty ones, coffee, tea, spices, and acidic foods such as tomatoes and citrus fruits. They are often present at night when lying down, because this position impairs upper digestive clearance. For this reason, nocturnal reflux is usually associated with increased complications, severe esophagitis, and intestinal metaplasia (BE) [16].

Extra-esophageal, or atypical, symptoms such as chest pain, chronic cough, laryngitis, asthma, and hoarseness can also be present and muddy the clinical picture of GERD; respiratory symptoms are due both to the reflux itself and to the bronchospasm induced by vagal stimulation. Their response to PPIs and antireflux surgery (ARS) is not as satisfactory as that of typical symptoms.

Only one-third of patients with erosive esophagitis have symptoms [7], and some people with a rich constellation of symptoms do not show esophagitis (nonerosive reflux disease—NERD). There is a strong correlation between longstanding esophageal reflux disease and adenocarcinoma, and the risk is associated with disease severity, frequency, and duration [17]. As a consequence, an endoscopy should always be performed in the case of alarm symptoms such as weight loss, dysphagia, gastrointestinal blood loss, anemia, chest pain, and epigastric mass on palpation [18,19].

It is paramount to perform a differential diagnosis, in order to exclude conditions with overlapping symptoms, such as cardiac disease, gallbladder diseases, gastrointestinal tumors, peptic ulcers, eosinophilic esophagitis, infections, functional heartburn, and benign esophageal disorders such as achalasia, distal esophageal spasm, nutcracker esophagus, and diverticula.

Mortality in esophagitis is linked to its complication, mostly to adenocarcinoma. It is otherwise infrequent, having been reported in the year 2000 to be as low as 0.46/100,000 [20]. The most frequent causes of mortality, besides neoplastic degeneration, are hemorrhage (38 %), ulcer perforation or esophageal rupture (29 %), aspiration pneumonia (19 %), and complications of ARS (11 %) [20].

Diagnosis

The goal of diagnostic tests is to assess the following:

the presence and degree of esophagitis;

the underlying cause of reflux esophagitis; and

the presence of complications.

The gold standard for detection of esophagitis is endoscopy. Patients presenting with typical reflux symptoms are commonly given an empiric course of PPIs; endoscopy is performed in those who fail or have an unsatisfying response to medical treatment. Upper endoscopy shows esophagitis only in 1/3 of patients with GERD symptoms [7] and is even less frequent after treatment with PPIs [21]. It is important to study the anatomy of the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) (presence of hiatal hernia or diverticula), to rule out complications and to obtain esophageal and gastric biopsies to exclude the presence of concurrent diseases (i.e.,Helicobacter pylori infection or eosinophilic esophagitis). Moreover, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is at times useful to assess the degree of esophageal wall involvement.

Twenty-four hours pH monitoring is the only technique capable of objectively detecting the presence of acidic reflux. It is helpful in case of symptoms with a negative endoscopy. Moreover, it should always be performed before ARS, both as a definitive confirmation test and as a predictor of surgical outcomes.

Impedance monitoring allows detection of both acidic and alkaline reflux, adding sensitivity to pH monitoring. It is particularly useful when performed in patients on PPI therapy, in which reflux becomes mostly nonacidic [22].

Esophageal manometry is used to evaluate LES function and esophageal peristalsis and to rule out the presence of esophageal motility disorders.

Barium esophagram is not helpful for the detection of esophagitis itself, but it rather reveals severe complications such as strictures and Schatzki’s rings and gives information on esophageal anatomy. It can also indicate the presence of a hiatal hernia, or other pathologic disease processes (e.g., neoplasms).

Bilitec consists of a fiber optic system for duodeno-gastroesophageal monitoring. It allows detecting duodenal reflux concomitantly in different sites of the upper GI, and it can be coupled with pH monitoring. It has been noticed that patients with concomitant gastric and duodenal reflux have a worse mucosal injury and higher severity of complications, compared to patients who present only one of the two components. Furthermore, patients with BE have a higher exposure to duodenal juice [23,24,25] than those who do not have metaplasia.

Treatment

There are three main treatment options for reflux-induced esophagitis: medical therapy, endoscopic treatment, and surgery. However, a multidisciplinary approach is often useful to address erosive esophagitis.

The therapeutic role and effectiveness of lifestyle modifications are controversial; however, these are often among the first advices given to patients after the diagnosis of GERD. The general recommendations are to avoid foods that stimulate LES relaxation such as tea, coffee, peppermint, chocolate, alcoholic beverages, and irritant foods such as citrus fruits and tomatoes. Moreover, it can be useful eating several hours before lying down, sleeping with the head lifted by 20 cm to favor esophageal clearance, and quitting smoking. Weight loss in overweight patients has been shown to improve symptoms even in refractory cases [26], likely by decreasing intra-abdominal pressure.

Medical therapy is the first line of treatment [27], with PPIs being the most effective group of medications [28]. PPIs should be prescribed to all patients with moderate to severe symptoms, or with a confirmed diagnosis of erosive esophagitis. PPIs are the most common class of medications prescribed in the USA [29]; they are very effective in healing esophagitis and improving its symptoms, and they are the most useful drugs in maintaining erosive esophagitis in remission. They should be initially prescribed at their minimum effective dose [30], and dose adjustment should be considered after evaluation of patient’s response. After 1–2 months of therapy, erosive esophagitis is healed in 84–95 % of patients; however, symptoms resolve only in 75–85 % [4]. PPIs block the hydrogen–potassium ATPase (H+/K+ATPase) by covalently binding it on to the apical surface of the parietal gastric cells. PPIs do not decrease the amount of reflux, but they only make the gastric content less harmful by modifying the acidic and nonacidic content: acid decreases from 45 to 3 %, while the nonacidic fraction increases form 55–97 % [31]. As a consequence, the reflux still occurs, but it is not acidic, with a pH commonly raised above 4. Although duodenal reflux is not affected by PPIs, and some authors suggested that their use might increase its damaging potential [32]: bile acids are inactivated when surrounded by acidic environment, but after PPI therapy, the pH raises above 4 and bile salts are converted to their ionized form, which are able to cross epithelial cell membrane and cause intracellular damage.

PPIs have also reduced efficiency in treating extra-esophageal symptoms [33], which are commonly caused by the presence of reflux more than its quality.

Patients with esophagitis often require a life-long therapy since medications do not address the disease’s etiology; in fact, about 80 % of patients will have recurrence of esophagitis approximately 1 year after the discontinuation of therapy [33].

Side effects of PPIs occur in about 1–5 % of patients and consist mostly of diarrhea, headache, constipation, abdominal pain, nausea, and rash [29]; when severely affecting the patients, they are managed by switching to a different medication, since a considerable degree of subjective variability exists, even though most of the side effects are class dependent. PPIs are generally safe, but concerns have been raised during prolonged use. The continuous suppression of gastric acid causes hypo- or achlorhydria, which might affect some nutrients’ absorption such as iron, vitamin B12, magnesium, calcium, and proteins [4]. Hypochlorhydria also decreases the acidic natural defense against bacteria, increasing the odds of overgrowth; an increased risk for Clostridium difficile, Salmonella, and Campylobacter-related diarrhea has been reported [34]. Increased incidence of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) has also been associated with PPI use [35].

Histamine2-receptor antagonists (H2RA) were also prescribed in the past, but several trials have established the superiority of PPIs over H2RA both in symptoms control and in esophageal healing, due to their capability of blocking the final step of acid secretion.

Surgery. Elective ARS can offer a definitive cure for esophagitis in selected patients, since it reestablishes a competent LES and allows for repair of concurrent hiatal hernias. Surgery has been shown to have the best outcome in patients with typical symptoms, objectively proven reflux, and good response to medical therapy [36]. The most common indications for ARS are dependence upon medical therapy, intolerance or noncompliance to therapy, and life-lasting treatment for young patients. ARS eliminates both acidic and biliary reflux in > 90 % of patients with BE [37], and the effect on alkaline reflux represents a major advantage of ARS over medical therapy. Randomized data have shown no difference in remission rate between maintenance PPI treatment and laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication at 5-year follow-up. The same study showed that while acid regurgitation was more prevalent in the PPI group, side effects of fundoplication, such as dysphagia, bloating, and flatulence, were more represented in the surgical group [38].

ARS has been reported to be more successful than medical therapy in stopping the progression to BE and adenocarcinoma [39]. Moreover, some studies have shown a higher likelihood of regression of Barrett’s metaplasia and dysplasia after ARS [40,41].

The most used surgical procedure is the Nissen fundoplication, introduced in 1956, which consists of confectioning a 360° gastric wrap around the esophagus. Floppy Nissen is a modification of the original technique, which allows reducing dysphagia and gas bloat syndrome that occurred in as many as 40 % of the patients with the traditional Nissen procedure. Floppy Nissen involves creation of a 2–3-cm-long gastric wrap around a bougie dilator (52–56 Fr).

In patients with severe motility disorders or suboptimal esophageal peristalsis, a partial fundoplication is generally performed in order to lower the risk of postoperative dysphagia. Partial posterior fundoplication (270° Toupet) has been introduced in the 1960s as an alternative to the Nissen fundoplication. In the short term, Toupet had good results in terms of reflux control, and it has been shown to decrease postsurgical dysphagia and bloating with respect to Nissen [4]. However, some studies report that it is less effective than total fundoplication, with a recurrence rate of reflux as high as 50 % after 5 years [42,43].

ARS is mostly performed laparoscopically, since minimally invasive techniques grant significant advantages over open ARS, in terms of decreased pain, faster recovery, shorter length of hospital stay, and low morbidity and mortality.

Surgical complications occur in less than 5 % of patients and mostly consist of bleeding and damage to the surrounding structures (spleen, esophagus, stomach, and vagus nerve). Postsurgical course is typically characterized by feeling of fullness and mild swallowing difficulties, especially with solid foods, but most patients return to normal after 6 weeks [44].

Nissen fundoplication has been reported to resolve reflux symptoms in up to 95 % of patients. Its most common long-term complication is dysphagia, occurring with a frequency ranging from 3 to 25 %, depending on the published series, and eventually leading to reoperation in up to 15 % of patients. Less frequently patients complain of early satiety, bloating, and flatulence.

ARS has been reported to heal esophagitis in up to 87 % of patients [45], with symptoms improvement in 95 %. Recurrence of esophagitis after fundoplication ranges from 5 to 15 % [46] and can lead to reoperation in about 6 % of patients [47]. Recurrence of esophagitis is usually associated with a failed surgical procedure.

Surgical costs are justified by long-term success, savings on prolonged medical therapy, overall better control of disease, and increased health-related quality of life (HRQoL) when compared to PPIs [48,49]. Importantly, according to some authors, ARS is superior to medical therapy in limiting the progression of low-grade dysplasia (LGD) to high-grade dysplasia (HGD) or cancer [50], and it leads to regression from LGD to BE in 93.8 % versus only 63.2 % with medical therapy [50]. This statistically relevant difference is probably due to the ability of surgery of limiting not only the acidic reflux, but also the biliopancreatic one.

New minimally invasive approaches for ARS include placement of a magnetic device around the GEJ to help maintaining LES continence or implantation of an electrical stimulator connected to electrodes in the LES that stimulates contractions. The LINX Reflux system used for sphincter augmentation through the employment of titanium beads showed encouraging results for uncomplicated GERD, reducing acid exposure with fewer side effects than ARS [51]. Even though these novel techniques have good potential, further studies are required to confirm their efficacy.

Finally, it should not be forgotten that although ARS lowers the risk of progression to cancer, it does not eliminate the risk of neoplastic progression in patients with BE, especially if there is recurrence of GERD. Endoscopic surveillance after surgery is recommended for patients with BE (Fig. 7.1).

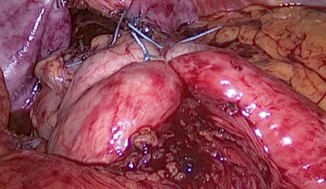

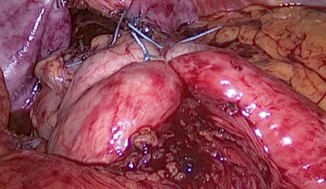

Fig. 7.1

Laparoscopic view of floppy Nissen fundoplication

Endoscopic techniques are relatively new approaches appealing for high-risk patients. These techniques include transoral incisionless fundoplication, suturing devices that create a gastroesophageal valve from inside the stomach, transmural fasteners, staplers, and radiofrequency devices used to induce muscular hypertrophy at the level of LES and gastric cardia. The efficacy of the latter approach may be due to increased wall thickness, LES pressure, decreased TLESR, decreased tissue compliance, acid sensitivity, and exposure [52]. However, according to some authors, endoscopic techniques are inferior to surgery in terms of decreased esophageal acid exposure, healing of esophagitis, and symptoms resolution [4].

Complications

Complications of esophagitis are strongly related to its chronicity, since continuous exposure to gastroduodenal reflux can progressively aggravate the disease.

Ulcers (Fig. 7.2): Erosive esophagitis can lead to ulcerations; these may be responsible for significant morbidities such as severe upper GI hemorrhages, strictures (12.5 %), and esophageal perforations (3.4 %) [53]. Chronic blood loss from active esophageal ulcers may cause iron deficiency anemia. Ulcerations are diagnosed with endoscopy, and a biopsy is always indicated to rule out malignancy. Ulcers in reflux esophagitis tend to be recurrent; therefore, appropriate therapy must be targeted to neutralize the underlying acid reflux and allow tissue healing.

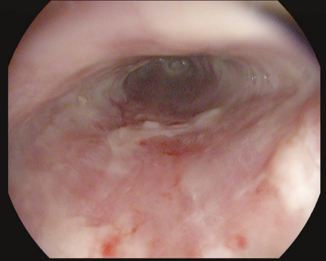

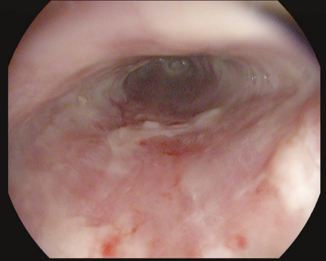

Fig. 7.2

Endoscopic view of grade C esophagitis with ulcerations

Esophageal shortening and narrowing occur as a result of repeated, prolonged injury: Acidic reflux causes inflammation, edema, and in the longrun destruction of muscolaris mucosae, leading to the formation of strictures at the level of the circular muscle; eventually, when fibrosis of the outer longitudinal muscle occurs because of transmural inflammation, the esophagus shortens. Esophageal shortening may also be found in patients with a failed antireflux procedure or with a mixed hiatal hernia that causes the upward migration of the GEJ [54]. 2 –4 % of patients undergoing antireflux procedures have a short esophagus [55].

Short esophagus is addressed surgically, most commonly using a Collis gastroplasty as an esophageal lengthening procedure. This can be completed laparoscopically, and an antireflux procedure is routinely added.

Strictures (Fig. 7.3) are the result of chronic inflammation and of repeated cycles of ulceration and healing, with subsequent fibrous tissue and collagen deposition, scar formation, and retraction. The process starts with a reversible phase characterized by edema and muscular spasm and then evolves to the formation of erosions. Location in distal esophagus, at the squamocolumnar junction, is a hallmark of peptic strictures, which are also usually shorter than 1 cm. Strictures observed more proximally are unlikely due to reflux. Peptic strictures can be found in 7–23 % of patients with untreated GERD with severe erosive esophagitis, mostly in the elderly, and in 25–44 % of patients who concomitantly have BE [56]. Their incidence has decreased steeply in parallel to the diffusion of PPIs. Factors predisposing to the development of peptic strictures include prolonged reflux, hypotensive LES, dysfunctional motility, hiatal hernia, bile reflux, and advanced age [53]. Symptoms are relatively nonspecific and influenced by stricture severity: dysphagia is the most frequent and can be accompanied by typical GERD symptoms. Food stasis causes halitosis and is also responsible for further mucosal damage and aspiration pneumonia.

Fig. 7.3

Barium esophagram showing esophageal stricture

Strictures can be divided into simple and complicated (Table 7.2) [57].

Simple | Symmetrical, focal, concentric, with an esophageal luminal diameter of > 12 mm allowing the endoscope passage |

Complicated | Long (> 2 cm) irregular, narrowing the luminal diameter to less than 12 mm |

Alternatively, strictures can be classified into three subtypes (mild, moderate, and severe), according to the parameters such as diameter, length, and difficulty in dilating the stricture [58]; this distinction aims to help choosing the most appropriate treatment for every subgroup.

Diagnostic workup for peptic strictures must include endoscopy to perform biopsies and rule out malignancies. Esophagram (Fig. 7.3) is very helpful in visualizing the esophageal narrowing and proves particularly valuable in severe strictures, when the endoscope cannot pass through. Therapy’s aim is to improve dysphagia, and avoid obstruction and recurrence.

Medical therapy plays a poor role once the stricture is already established; however, PPIs are fundamental to heal the concomitant esophagitis and prevent disease progression. Dilation is the primary therapy [59] and should be the first operative step: It can be attempted with the endoscope itself when the strictures are mild, but it is usually performed through bougies (Savary-Gilliard or Maloney) or balloon-type dilators, with or without guidewire assistance. Complex strictures often require guidewire and fluoroscopy for safe placement of the dilators. Self-dilation can seldom be offered to carefully selected patients [37].

Dilation is generally safe; however, the potential risk of hemorrhage and perforation ranges between 0.1 and 0.4 % [59]. The occurrence of procedural complications can be reduced by performing the dilation progressively through multiple sessions and avoiding dilating more than 3 mm each time [37]. Dilation should be associated with either acid suppression medical therapy or ARS to enhance success [60]. However, even with aggressive therapy, only 60–70 % of patients have complete resolution of symptoms, and multiple repeated dilations are often required [59]. To date, no randomized controlled trials have compared ARS versus medical management and serial bougienage; however, a retrospective study suggested that optimal reflux control with ARS results in decreased need for repeated dilation and better symptomatic outcome [61].

If satisfying dilation is not achieved after multiple sessions, strictures are deemed refractory, and the use of endoprosthesis (metal or plastic stent) should be considered [4]. Esophageal stenting and local steroid injections can be an auxiliary therapeutic option for refractory or recurrent strictures; the latter in particular has the capacity of inhibiting the inflammatory response, limiting collagen deposition [62]. Combining these two treatments with acid suppression therapy successfully reduces both the need for dilations and the time between sessions [37]. Presence of hiatal hernia, ineffective acidic therapy (low dose, poor compliance), or alkaline reflux may predispose to disease recurrence.

Rarely, esophagectomy is indicated for recurrent or refractory strictures with underlying intractable esophagitis and a severely damaged esophagus [58]. Most commonly, an esophagectomy is necessary with gastroplasty or colonic/jejunum interposition [63].

Schatzki’s Rings are circular narrowed areas constituted by esophageal and gastric mucosa with fibrous and connective tissues, which are usually observed at the GEJ. They have a similar etiology to peptic strictures, and they also lead to dysphagia causing food impaction in the esophageal lumen. If this event occurs abruptly, endoscopic food extraction is indicated; the procedure is safer when performed with an endoscope covered by an overtube, in order to avoid aspiration in the bronchial tree. Conversely, pushing food in the stomach is not advisable as it may lead to perforation. Schatzki’s rings are diagnosed through barium swallow and endoscopy. The therapy of choice is bougie dilation associated with PPIs that are administered after dilation, which dramatically reduce esophageal rings’ incidence and recurrence.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree