Serrated Polyps

Serrated Adenomas

Serrated adenomas constitute 1% to 2% of colorectal adenomas (261,262). Patients range in age from 15 to 88 years, with a mean of 63 years. The serrated adenomas are distributed throughout the colorectum but with a predisposition of larger lesions (measuring >1 cm) to involve the right colon. They occur as single or multiple lesions. Multiple lesions may form part of a polyposis syndrome (see Chapter 12). The adenomas may be pedunculated or sessile. Serrated adenomas lack any gross features that allow their distinction from ordinary adenomas.

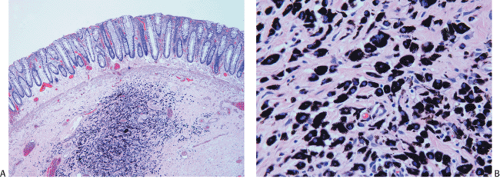

Histologic examination at low magnification discloses a pattern of serrated glands lining the crypts, producing a pattern reminiscent of the glands in hyperplastic polyps (Fig. 14.70). However, the stratified cells lining the glands appear less mature than those found in hyperplastic polyps, and they are dysplastic (Figs. 14.70, 14.71, and 14.72). Serrated adenomas are distinguished by the presence of goblet cell immaturity, upper zone and surface mitoses, and prominent nucleoli. Monotonous, mucin-depleted, often eosinophilic

cells exhibiting nuclear pseudostratification and occasional loss of the polarity line the glands (Fig. 14.71). However, some serrated adenomas contain significant amounts of mucin. Nuclear:cytoplasmic ratios are greater in serrated adenomas than in hyperplastic polyps but slightly less than those seen in traditional adenomas. As the cells become increasingly atypical, they lose their stratification and the nuclei become rounder, more pleomorphic, and large. Additionally, glandular crowding and luminal budding begin to appear (Fig. 14.72). The surfaces of serrated adenomas, particularly those that are sessile, may show papillary tufting. The collagen table underlying the free surface is not as thickened as in hyperplastic polyps and is thinner than that seen in the normal mucosa, resembling more the collagen table of adenomas (234).

cells exhibiting nuclear pseudostratification and occasional loss of the polarity line the glands (Fig. 14.71). However, some serrated adenomas contain significant amounts of mucin. Nuclear:cytoplasmic ratios are greater in serrated adenomas than in hyperplastic polyps but slightly less than those seen in traditional adenomas. As the cells become increasingly atypical, they lose their stratification and the nuclei become rounder, more pleomorphic, and large. Additionally, glandular crowding and luminal budding begin to appear (Fig. 14.72). The surfaces of serrated adenomas, particularly those that are sessile, may show papillary tufting. The collagen table underlying the free surface is not as thickened as in hyperplastic polyps and is thinner than that seen in the normal mucosa, resembling more the collagen table of adenomas (234).

Sessile Serrated Polyps

Torlakovic and Snover recognized in 1996 that the “hyperplastic polyps” seen in association with hyperplastic polyposis differed morphologically from traditional hyperplastic polyps (263). In addition, Goldstein et al (264) found similar

features among serrated polyps that preceded the development of microsatellite instability (MSI)-positive colon cancers. The morphologic criteria for these so-called sessile serrated polyps are summarized in Table 14.13.

features among serrated polyps that preceded the development of microsatellite instability (MSI)-positive colon cancers. The morphologic criteria for these so-called sessile serrated polyps are summarized in Table 14.13.

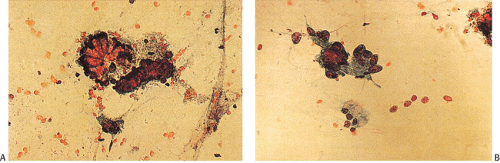

FIG. 14.68. Submucosal tattoo. A: Endoscopic mucosal resection of a previous polypectomy site. A submucosal collection of histiocytes containing black pigment is present. This represents the tattoo site placed by the endoscopist at the time of the initial polypectomy. B: Higher-power view showing histiocytes containing granular black India ink pigment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|