(1)

Department of Surgery, Keck Medical Center of University of Southern California, 892 Huntington Garden Drive, San Marino, 91108 Los Angeles, CA, USA

Keywords

Gastroesophageal refluxLower esophageal sphincterSphincter augmentationMagnetic sphincter augmentationLINXAnti-reflux surgeryNissenPartial fundoplicationIntroduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common foregut disease in the world and accounts for approximately 75 % of all esophageal pathology [1]. The majority of afflicted patients have mild disease and are successfully managed with lifestyle modifications and acid suppression medication [2]. Fortunately, progression to erosive disease occurs in only 13 % of patients over 5 years [3]. Unfortunately, progression to Barrett’s esophagus occurs in 10 % of patients over 5 years [3]. In these patients, the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) progresses from transient to permanent failure. The impetus to identify and counsel patients with progressive disease regarding the need for surgical therapy is critical. This message goes largely unheeded by the gastroenterologist due to their lack of confidence in the durability of a fundoplication and concern over the side effects of the operation. Consequently, the early referral of a patient with symptoms and signs of progressive disease for surgical therapy is resisted. Further, there is widespread concern that not all surgeons are sufficiently experienced in evaluating esophageal patients, many are not knowledgeable enough to select the proper anti-reflux procedure, and some are not sufficiently trained to properly perform the procedure [4, 5]. The advent of sphincter augmentation procedures allows early treatment of patients who have clinical flags of early progressive disease. This will potentially mitigate the risk of the disease progressing to chronic erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus , and esophageal carcinoma.

Role of LES Augmentation for Early Progressive Disease in GERD

Determining the Status of the LES

The discovery of the lower-esophageal high-pressure zone, or LES as it was late named, led to the realization that almost half of the patients with confirmed GERD by 24-h pH monitoring have a normal LES on a motility study performed off medications, at rest, in the recumbent position, and after an overnight fast [6]. The etiology of reflux in patients with a normal LES is due to dynamic failure of the LES. This consists of transient openings of the LES when challenged by gastric distension or non-pressurized gastric dilation [7, 8]. These events are called transient LES relaxations (TLESRs) and were first described by Dodds in 1982 [9]. Gastric distension occurs with overeating or excessive dry swallowing. Each dry swallow carries with it saliva and the 15 cc of air contained within the pharyngeal space. The swallowed food and air collect in the stomach and if excessive cause pressure-generated gastric distension. Gastric dilation, on the other hand, is due to normal physiologic relaxation of gastric muscle with the ingestion of a meal and is termed adaptive relaxation [10]. Gastric dilation is not associated with an elevation of intragastric pressure .

There are two proposed explanations for the occurrence of TLESRs. One, favored mainly by gastroenterologists, proposes that TLESRs are due to a neuro-mediated reflex initiated by pressurized gastric distension or non-pressurized dilation from gastric adaptive relaxation induced by a meal [11]. These conditions stimulate stretch receptors in the gastric fundus that in turn stimulate vagal afferents that relay the input from the receptors to the medulla. Medullary nuclei then orchestrate the efferent limb of the reflex via the vagal and phrenic nerves to elicit prolonged LES relaxation, crural diaphragm inhibition, and distal esophageal shortening [12].

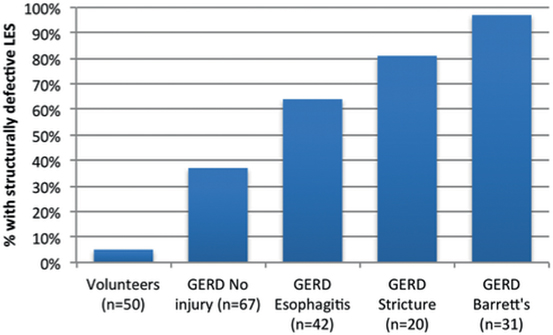

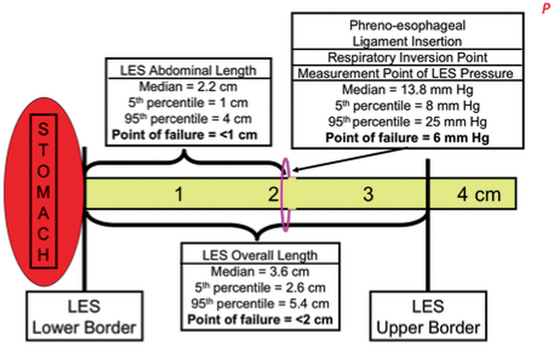

The second explanation, favored mainly by surgeons, proposes that TLESRs are due to transient shortening of the LES length with the effacement of the LES by pressurized gastric distension or non-pressurized dilation due to meal-induced adaptive relaxation. Normally, in the fasting state and resting recumbent position, the median overall LES length is 3.6 cm and the intra-abdominal length is 2.2 cm [13]. With gastric distension or dilation, the length of the LES shortens as the LES is effaced and taken up by the gastric fundus [8]. When gastric distension or dilation is excessive, the length of the LES shortens to the point where the corresponding pressure of the LES can no longer maintain closure, the LES opens and gastroesophageal reflux occurs [13]. This occurs predominately during the postprandial period [14] .

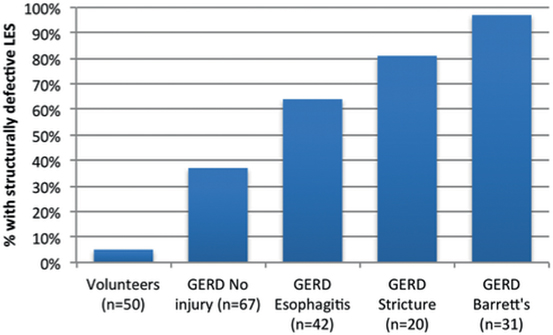

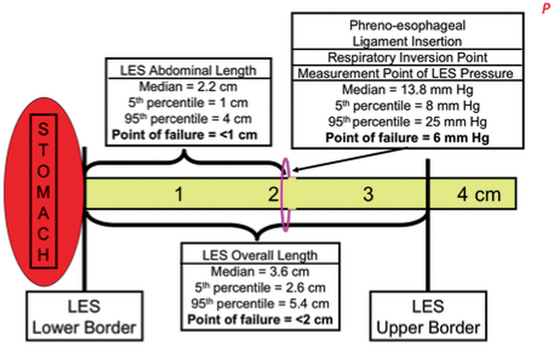

During effacement and shortening, the distal end of the LES is taken up by the fundus and exposed to gastric juice causing inflammation and ulceration of the effaced portion of the distal LES [8]. If the inflammation continues, it can permanently reduce the abdominal length to < 1 cm and limit the ability of the LES to respond to intra-abdominal pressure challenges [15–18]. Similarly, persistence of the inflammation can reduce the overall length of the LES to < 2 cm and limit its ability to resist gastric distension or non-pressurized dilation [8, 13]. In both situations, a transient failure of the LES due to gastric distension or dilation has advanced to a permanent failure of the LES due to the loss of abdominal and overall length of the LES. The last component of the LES to go is its pressure due to extensive inflammatory injury. Figure 8.1 shows that the more severe the inflammatory injury to the LES is, the greater the prevalence of a permanently failed LES. Permanent failure of the LES is identified when one or more of the following LES abnormalities are seen on a motility study: an abdominal length of < 1 cm, an overall length < 2 cm, and a resting pressure less than 6 mmHg [6]. When all three components are abnormal, the LES is completely destroyed and will likely require reconstruction with a fundoplication [6, 19] .

Fig. 8.1

Increase in the incidence of a permanently failed LES in GERD patients with progressive degrees of esophageal injury. GERD gastroesophageal reflux disease. (Adapted with permission from Ref. [58])

Figure 8.2 is a schema of the LES based on the median measurements in 50 normal subjects [6]. The median and 5th and 95th percentiles for the LES abdominal length, overall length, and pressure are tabulated along with their point of failure. The most common component to permanently fail is abdominal length, followed by the overall length. The least common permanent failure is a hypotensive LES pressure. Individuals vary in their propensity for transient failure of the LES. Failure from challenges of increased intra-abdominal pressure are dependent on the innate LES abdominal length. Failures from challenges of gastric distension or gastric non-pressurized dilation are dependent on the innate LES overall length.

Fig. 8.2

Schema of the components of the LES: pressure, overall length, and abdominal length. The median value for each component and their 5th and 95th percentiles are listed and illustrated. The “point of failure” is the value for a specific component at which esophageal acid exposure becomes abnormally independent from the values of the other components. LES lower esophageal sphincter

Performance of a fundoplication on a patient with a normal LES that dynamically fails leads to excessive postprandial symptoms after surgery (Table 8.1 ) [20]. This occurs because the fundoplication prevents the shortening and opening of the sphincter to relieve postprandial distension or excessive dilation [21]. As would be expected, these patients complain of bloating, the inability to belch, and social problems associated with increased flatus. These side effects are less frequent and severe when a fundoplication is placed over an LES that has been partially or completely destroyed (see Table 8.1) [20].

Table 8.1

Incidence of side effects post Nissen related to preoperative LES manometrics. (Reprinted with permission from [20])

Normal LES (n = 43) (%) | Defective LES (n = 57) (%) | |

|---|---|---|

Symptomatic gas bloat | 44 | 23* |

Increased flatus | 75 | 48* |

The realization of the differences in side effects between a permanently failed LES and an LES that transiently fails has led to the development of surgical procedures specifically designed to prevent transient LES failure and block the progression to permanent failure [22]. The benefit of such procedures is the improvement of LES function with minimal surgical dissection and minimal to no side effects [22]. It is hoped that the effectiveness and gentleness of these procedures will encourage their use earlier in the course of GERD, when the symptoms and signs of progressive disease first appear. It is expected that these procedures will interrupt the progression of LES damage, prevent its permanent failure, avoid the complications of end-stage GERD, and eliminate the risk of Barrett’s esophagus .

How to Identify the Patient for Sphincter Augmentation

The two primary treatment options for patients with GERD are long-term acid suppressive therapy or surgery. Acid suppression therapy with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is the first-line therapy. Medical therapy is focused on reducing the acidity of the gastric juice while accepting that reflux continues to occur unabated [23]. Consequently, 13 % of patients will have progression of their disease over 5 years while on acid suppression therapy [3]. Clinical flags of progression are evidence that PPIs are becoming less effective over time. The ineffectiveness of PPIs can be identified by the emergence of incomplete symptom relief, the onset of new symptoms, the need to escalate the dose of PPIs to achieve symptomatic relief, the development of nocturnal symptoms, and the onset of regurgitation and/or extra-esophageal symptoms [3, 18]. The clinical signs of progression are related to the deterioration of the LES and include bipositional reflux on 24-h esophageal pH monitoring, abnormal esophageal acid exposure on both days of a 48-h pH monitoring study, a motility study showing a defective LES, and/or persistent esophagitis despite therapy [3] .

Laparoscopic fundoplication has been plagued with well-described side effects, variable outcomes when done by less experienced surgeons and high recurrence rates. Consequently, there is a reluctance for physicians to refer patients with symptoms and signs of progressive disease for surgery early in the course of their progression. Studies on the perception patients have about laparoscopic fundoplication show that 90 % are concerned about long-term failure of the procedure, 75 % are concerned about the possibility of dysphagia after the procedure, and 41 % are concerned about reversing the fundoplication if necessary [25]. Further, patients are concerned about developing new symptoms after fundoplication such as bloating in 31–44 % of patients, increased flatus in 47–57 % of patients, and the inability to belch or vomit [26–28].

Consequently, it is reasonable that patients with progressive disease become frustrated by the ineffectiveness of the medical therapy and the lack of a dependable and durable surgical solution to their problem that is free of side effects. The specific issues they are anxious about are the persistence of symptoms while on PPI therapy, lifelong dependency on medication, disease progression while on medication, the side effects of medication, and the finality and side effects of a surgical fundoplication. They are asking themselves, what does this mean for me in the long term? The limitations of both medical therapy and laparoscopic fundoplication leaves this group of patients in the equivocal position of either tolerating a lifetime of drug dependence with incomplete symptom relief and the risk of progressive disease or accepting the risk of a surgical procedure that alters gastric anatomy, has significant side effects, and is not easily reversible (Table 8.2). To grasp how significant these factors are is reflected in the number of surgical anti-reflux procedures now performed. Currently, fewer than 30,000 fundoplication procedures are performed annually in the USA. This corresponds to less than 1 % of the 20-million medically treated GERD population [29]. Fortunately, there is a new development that can help patients who are frustrated by the ineffectiveness of their medical therapy and the side effects and durability of surgical therapy. The proper evaluation of these patients can identify those who likely have early progressive disease and would benefit from early surgical intervention with new devices that augment the failing LES .

Open 1986 (1) (%) | Lap 1998 (2) (%) | Lap 2006 (3) (%) | Lap 2011 (4) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Inability to belch | 36 | 20 | – | – |

Inability to vomit (if tried) | 63 | 25 | – | – |

Increased flatus | 38 | 47 | 40 | 57 |

Symptomatic gas bloat | 15 | 44 | 31 | 40 |

Persistent dysphagia | 3 | 2 | 2 | 11 |

Improved understanding of the LES has led to the development of procedures that augment the sphincter without causing side effects. The procedures are applicable to patients who have earlier evidence of progressive disease manifested by incomplete relief of their symptoms with PPI therapy. On clinical testing, these patients have increased esophageal acid exposure, adequate esophageal body function, and a normal or near-normal LES. As discussed above, such patients have a dynamic failure of the LES due to excessive shortening of its overall length when challenged by gastric distension or non-pressurized dilation. A promising surgical therapy for these patients is the implantation of a new device that focuses on augmenting the function of the existing LES. The anatomy of the hiatus is not altered; unlike a fundoplication, and the procedure does not attempt to improve the exposure of the abdominal length of the LES to the positive environmental pressure of the abdomen. There are three such operations: augmentation of the LES by reducing it’s compliance with radio frequency [30], by increasing it’s tone and reducing it’s compliance with electrical stimulation [31], and preventing it’s effacement with a ring of magnetic beads [22]. Of these, the most extensive clinical experience has been with magnetic sphincter augmentation using a device known as the LINX. The LINX remedies dynamic failure of the LES by preventing shortening of its overall length when challenged by gastric distension or non-pressurized dilation [32]. The procedure requires only limited dissection, does not alter the anatomy of the esophageal hiatus, has minimal side effects, and is reversible (Table 8.3) . The procedure requires the implantation of a device known as the LINX. It consists of a series of magnetic beads connected to each other by independent wires. It is placed, using a laparoscope, around the esophagus at the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ). Only minimal dissection is done which does not alter the hiatal anatomy, and preserves of the phrenoesophageal ligament. The LINX device can be easily removed if necessary, thereby preserving the option for a subsequent fundoplication if necessary. More importantly, the LINX device produces little to no persistent side effects and was designed to limit the technical variability that occurs with fundoplication. The goal was to develop a more standardized and gentler anti-reflux procedure that is applicable and acceptable to patients with early progressive disease. The initial studies of the LINX procedure showed improved GERD–HRQL scores in patients who partially respond to PPIs. Five years after the procedure, 85% of patients no longer required the use of PPIs, their median esophageal acid exposure was normalized, the side effects of gas bloat were less than 2%, the new onset of persistent dysphagia was <1% and 98% maintained the ability to vomit and belch (see Table 8.3) [32, 33]. To date, the LINX device has been implanted in over 1000 patients worldwide, and the outcomes have confirmed its safety and efficacy [32]. It is still uncertain if the LINX device will be effective in patients with a completely destroyed LES. Consequently, at present, patients with more advanced diseases, such as a hiatal hernia > 3 cm, endoscopic grade C or D esophagitis, or endoscopic Barrett’s esophagus are not considered candidates for sphincter augmentation and should be treated with a traditional surgical fundoplication. Future studies will compare reflux control and side effects with the LINX device to varying degrees of fundoplications. In a propensity-matched case–control series comparing laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with the LINX in patients with similar disease severity, 1-year outcomes showed similar efficacy in terms of symptom control and PPI use with significantly less gas bloat in the LINX patients [34]. It should be understood that the device is not intended to be a substitute for the Nissen and is intended for use earlier in the disease process in patients with normal or minimal deterioration of their LES to prevent the progression to permanent LES failure and the complication of end-stage GERD. Figure 8.3 is an algorithm for the surgical management of the GERD patient that incorporates the decisions that need to be made in the selection of the correct surgical procedure .

Table 8.3

Side effects following the LINX

Surgical endoscopy | NEJM | American College Surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|

Follow-up time (months) | 48 | 36 | 36 |

Dysphagia (moderate or severe) | 0 %a | 0 %a | 0 %b |

Ability to belch | 95 % | 98 % | 99 % |

Ability to vomit | 95 % | 98 % | 99 % |

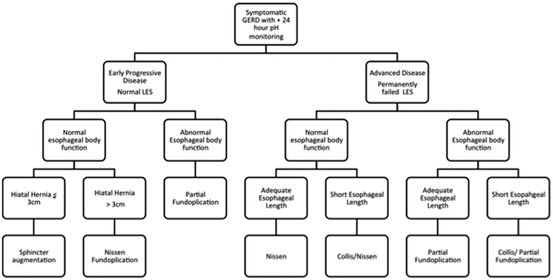

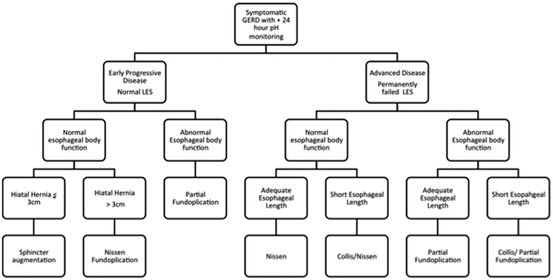

Fig. 8.3

Algorithm of surgical treatment for GERD patients with early progressive disease and a normal or near-normal LES and those with advanced disease and a permanent failed LES

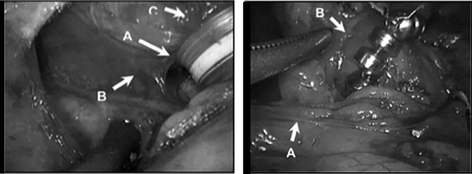

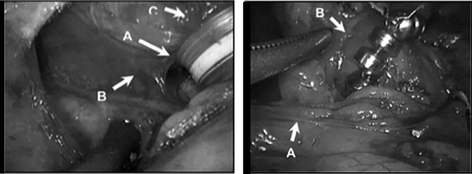

The principles of implanting the LINX device are proper sizing of the device, proper positioning of the device, and constructing, with limited dissection, a tunnel behind the esophagus, between its posterior wall and the posterior vagus nerve. Through this tunnel, the LINX device is passed. The phrenoesophageal ligament is not dissected and the esophageal hiatus is not explored (Fig. 8.4). Guarding the integrity of the phrenoesophageal ligament during LINX implantation is imperative as the ligament functions to maintain the abdominal length of the LES. This is in contrast to a fundoplication where the hiatus is completely dissected out, and the LES is enveloped with the gastric fundus to provide a conduit to transmit intra-abdominal pressure around the LES. The critical benchmark steps for the LINX procedure are listed in Table 8.4. A detailed description of the implantation of the LINX device has been previously published and is available for reference [33].

Fig. 8.4

Placement of the LINX device. (Left) Surgical dissection for the implantation of the LINX device. a Surgically dissected tunnel for the LINX device located between the posterior wall of the esophagus and the posterior vagus nerve. b Posterior vagus nerve. c Esophagus. (Right) LINX device, a bracelet of magnetic beads, in its proper implanted position, that is, encircling the esophagus just above the esophageal-gastric junction. a Hepatic branch of the anterior vagus nerve. b Insertion of the phreono-esophageal membrane. (Reprinted with permission from [59])

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree