18.8 Surgical Management: Conservative Surgery

In young patients who desire fertility, conservative surgery should be attempted. The goals of conservative operative procedures are to remove all implants, resect adhesions, reduce the risk of recurrence, and restore the involved organs to a normal anatomic and physiologic condition. When endometriosis is severe and obliterates the surgical planes, dissection can be very difficult, making the da Vinci robot helpful. In patients with severe disease and the desire for fertility, the posterior cul-de-sac (Fig. 18.3) and tubo-ovarian anatomy must be normalized to increase fertility [1]. Much debate has been raised over ablation versus resection of endometriosis. As long as the lesions are completely eradicated the method of removal is inconsequential.

Conservative surgery should not be considered definitive treatment for endometriosis. Although such procedures are seldom curative, they often improve the likelihood of pregnancy and offer temporary pain relief and improved quality of life [1, 4, 26]. Reoperation is not uncommon because of recurrence of endometriosis or progression of residual microscopic disease. The rate of repeat intervention is directly related to the extent of disease, the completeness of removal, the ability to conceive postoperatively, the use of postsurgical suppressive therapy, and the use of fertility-enhancing medications [27]. Because pregnancy is a progesterone-dominant state, many women will have symptomatic improvement during pregnancy. In conjunction, women who undergo infertility treatment are more likely to have a recurrence of the disease because of the high estrogen state.

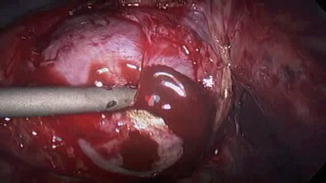

Fig. 18.3

Posterior cul-de-sac that has been obliterated by endometriosis, resulting in the loss of surgical planes and scarring of both ovaries

18.9 Surgical Management: Hysterectomy and Bilateral Salpingo-oophorectomy

Radical surgery is indicated for patients who no longer desire fertility and who have severe symptoms that are unresponsive to medical or conservative surgical treatment. Procedures include hysterectomy, salpingectomy, possible oophorectomy and the excision of deeply infiltrating endometriosis. This could involve partial resection of the bowel, bladder, or ureter in extreme cases [20]. Bilateral oophorectomy is done for the purpose of decreasing the estrogen that sustains and stimulates the ectopic endometrium, but there is a more recent trend towards ovarian preservation. In advanced disease, the ovaries may be encased and densely adherent to the pelvic sidewall. Ovarian dissection entails the risk of injury to the ureter, major blood vessels, and the bowel. A retroperitoneal approach can isolate the ureter throughout its course to ensure complete removal of ovarian tissue and prevent ovarian remnant syndrome. Some advocate the preservation of one ovary to avoid the long-term health risks associated with premature surgical menopause. However, such surgeries are not considered definitive and future surgery may be required to remove the remaining ovary for. In 2009, a large prospective study with 24 years of follow up reported that patients who underwent bilateral oophorectomy before the age of 65 had an increased risk of all-cause death. Since publication, many gynecologists have hesitated to perform oophorectomy. In general, it is better to begin with conservative surgery and then proceed to definitive surgery that may include oophorectomy. Oophorectomy should be considered only after the patient has had a trial of GnRH agonists to induce short-term cessation of ovarian function.

It must be noted that because of the obliteration of tissue planes from endometriosis, ovarian remnant are sometimes left behind during definitive surgery. That remnant can continue to cause proliferation of endometriosis. An ovarian remnant may be palpable on pelvic examination or may be visualized on pelvic ultrasound. Because of the scarring involved, it is often difficult to locate and excise these lesions. Ureteral stents can be helpful in patients with suspected ovarian remnant syndrome to help identify the ureters during surgery.

18.10 Postoperative Management

Although surgery can eradicate the visible endometriotic lesions, there is a role for post-operative medical suppression of the microscopic lesions. The goal of medical therapy is to avoid the estrogen surge that comes with ovulation and promote decidualization of the endometriotic lesions [28]. Patients who do not desire immediate fertility generally benefit from an oral contraceptive pill or a progesterone containing intra-uterine device. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, which decrease total estrogen, can be used short term post-operatively, but are slightly controversial in terms of pain improvement of decreased recurrence [29, 30]. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists might be beneficial in women with severe disease who are undergoing a two-stage surgical procedure to suppress regrowth of endometriosis between the two surgeries.

In pre-menopausal women who have undergone total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, treatment with a low dose of estrogen not only avoids the symptoms of menopause, but also maintains cardiovascular and bone health. A joint patient-physician decision must consider the suppression of endometriosis, patient comfort, and overall health.

For women with chronic pelvic pain, the role of a multi-disciplinary team for long-term pain management and treatment is indicated. This team could include a chronic pelvic pain specialist, pelvic floor physical therapist, psychologist, pain management anesthesiologist and acupuncturist.

18.11 Extragenital Endometriosis

Although endometriosis is classically found in pelvic organs, it can be found outside of the genital tract in up to 12 % of cases [3]. The most common sites for extragenital endometriosis are the urinary system and the bowel, but endometriosis can also be found in the lung, diaphragm, liver, and even brain.

Endometriosis may spread to the urinary system in 1–5 % of women with symptomatic endometriosis [3]. Urinary tract endometriosis most commonly affects the bladder, but can also be seen as involving the ureter and the kidney. Endometriosis of the urinary tract tends to be superficial, but may be invasive and cause significant symptoms. The signs and symptoms of bladder endometriosis include suprapubic pain, dysuria, hematuria, frequency, and dyspareunia. These symptoms may be cyclic in nature, but often are not associated with the menstrual cycle. Clinicians should consider endometriosis in cases of refractory and unexplained urinary complaints. If bladder endometriosis is suspected, a computed tomography (CT) scan with IV contrast and delayed images to evaluate the ureters should be completed. In cases of recurrent hematuria or a strong suspicion for endometriosis, a cystoscopic examination is indicated. If any lesions are noted on cystoscopy, a biopsy is recommended to confirm the diagnosis of bladder endometriosis. The majority of cases of bladder endometriosis are superficial lesions. For full-thickness lesions, segmental bladder resection may be indicated [3, 20].

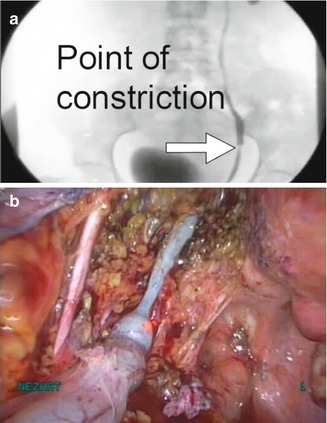

Ureteral endometriosis is less common than that of the bladder, but can have more devastating consequences due to obstruction. The distal third of the ureter is the most common site of involvement, with the left ureter being involved more often than the right. Signs of ureteral endometriosis include hematuria, flank pain, back pain, abdominal pain, and dysuria. As with bladder endometriosis, symptoms may or may not be cyclical. Computed tomography with IV contrast or IV pyelogram may show hydroureter or hydronephrosis (Fig. 18.4). If the ureter is compressed by endometriosis, causing hydroureter or hydronephrosis, surgical treatment via ureterolysis is mandatory (Fig. 18.5). Ureteral stent placement may be helpful in these cases. If the endometriosis invades through the ureter, segmental resection with either reimplantation or ureteroureterostomy is indicated, depending on the level of the obstruction [20].

Endometriosis of the kidney is exceedingly rare and only merits a brief mention in this chapter. Signs and symptoms are similar to those of ureteral endometriosis. In addition, a renal mass may be noted on imaging. When this occurs, the mass is generally treated with partial or complete nephrectomy [3].

The gastrointestinal tract is involved in 3–37 % of women with endometriosis [31]. Endometriotic implants are most commonly found on the rectosigmoid colon, appendix, rectum, and cecum. Bowel endometriosis may be completely asymptomatic, but often will present with diarrhea, constipation, rectal bleeding, dyschezia, hematochezia or abdominal pain. The evaluation of a patient with suspected gastrointestinal endometriosis should include a fecal occult blood test, a colonoscopy, and possibly a CT scan or MRI prior to surgery. These tests rarely change in the treatment of the patient with endometriosis, but are helpful to rule out other causes of bowel dysfunction, especially malignancy [3, 32]. Operative laparoscopy, often facilitated by the robot, is performed to treat endometriotic implants on the intestinal wall, appendix, and rectovaginal space (Fig. 18.6) [33]. The surgery performed varies, depending on the patient, but can include appendectomy, disc excision, or bowel resection. Bowel resection should be reserved only for those patients who continue to have symptoms despite more conservative forms of treatment or present with obstructive symptoms.

Thoracic endometriosis, although less common than endometriosis of the genitourinary or gastrointestinal system, is another important site of extragenital endometriosis. The most common presenting symptoms are chest pain, catamenial pneumothorax, catamenial hemoptysis, catamenial hemothorax, or lung nodules [34, 35]. Women should be asked about pleuritic, shoulder, or upper abdominal pain occurring with menses because they often do not correlate the symptoms. The diagnosis requires a high clinical suspicion and a thorough history during the evaluation. The evaluation of the patient with suspected thoracic endometriosis may include chest radiograph, chest CT, chest MRI, bronchoscopy, and thoracentesis to evaluate for other etiologies of the symptoms. If it has been determined preoperatively that the patient may have thoracic endometriosis, robotic or laparoscopic thoracic surgery should be performed by a cardiothoracic surgeon at the time of pelvic surgery [35]. During the video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, any endometriotic implants should be ablated or resected and any scarring of the lung to the thoracic side wall should be treated surgically (Fig. 18.7 and 18.8).