Fig. 7.1

Port placement including robotic ports (red) (a) and assistant ports (green) (b)

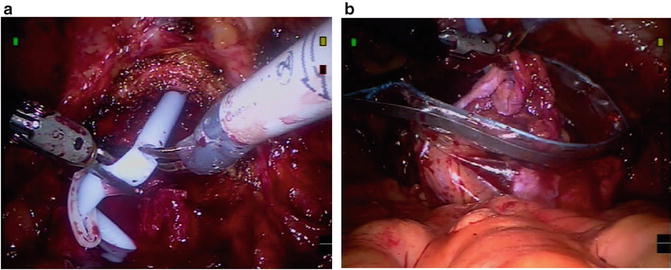

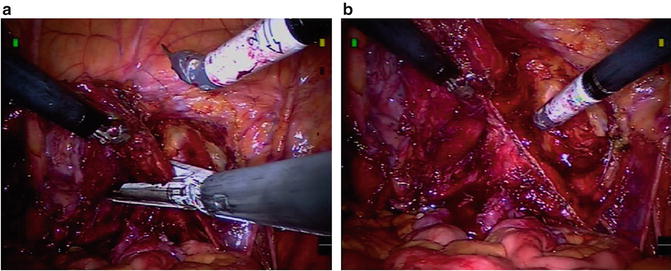

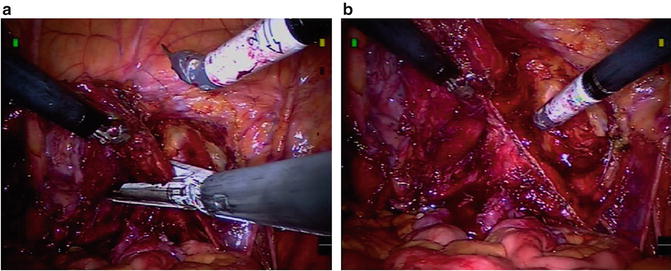

Fig. 7.2

Dissection (a) and bipolar fulguration and division (b) of ovarian pedicles (IP ligament)

Procedural Steps

See Table 7.1 for list of instruments and accessories.

Table 7.1

Instruments and accessories

A. Recommended laparoscopic instruments |

• 5 mm endoscopic long suction irrigator (45 mm) • 5 mm endoscopic scissors • 5 mm endoscopic locking grasper • 5 mm endoscopic needle driver (for passing suture) • 10 mm specimen retrieval bag |

B. Recommended sutures/clips |

• Dorsal vein stitch – 0 Vicryl on CT-2 (6 in.) • Ureteral and terminal ileum tags – 3-0 Vicryl on SH (full length) • Anastomosis stitch (for orthotopic diversion) – 3-0 Vicryl (or Monocryl) suture on RB-1 • Neobladder creation (intracorporeal diversion) – 2-0 Vicryl suture on SH – Stapler with vascular load • Ureteroenteric anastamosis (intracorproeal diversion) – 4-0 Vicryl suture on RB-1 suture • Hem-O-lock® (Weck Closure Systems, RTP, NC) large and extra large clips with endoscopic applier • Endovascular stapler/cutter with 60 mm vascular loads (e.g., Endo-GIA, Covidien, Mansfield, MA) |

C. Recommended robotic instruments |

• Two large needle drivers • Hot shears (monopolar curved scissors) • Maryland bipolar forceps • Cadiere bipolar graspers • Double fenestrated graspers (intracorporeal diversion) |

Divide Ovarian Pedicles (Infundibulopelvic [IP] Ligament)

After any sigmoid adhesions of the left side bladder and pelvis are released sharply, all of the small bowel is vacated from the pelvis. The ovarian pedicles (IP ligaments) are identified on each side superior and lateral to the ovaries themselves (Fig. 7.2a). A window is developed in the broad ligament isolating the ovarian pedicle. They can be ligated with the use of hemolock clips or alternatively fulgurated with the use of bipolar forceps before sharp division (Fig. 7.2b). With the posterior peritoneum overlying the ovarian pedicles incised, this peritoneal incision is extended along the broad ligament lateral to the fallopian tubes in the direction of the uterus and bladder. When the round ligaments are encountered, they are divided with the aid of the bipolar forceps and monopolar scissors. The fundus of the uterus is now freely mobile allowing greater manipulation of the uterus if desired and better visualization of the pelvic structures.

Isolate Ureters

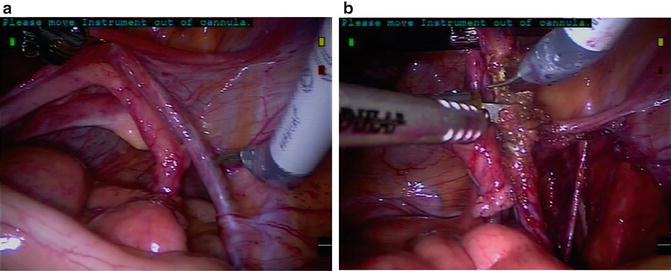

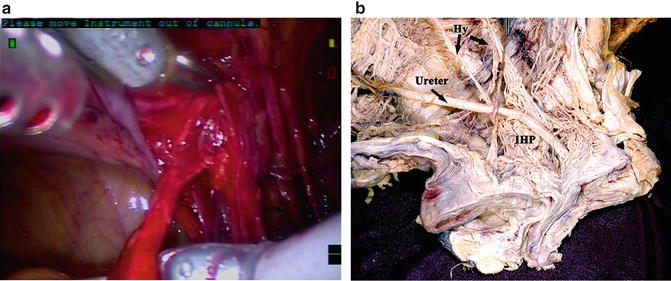

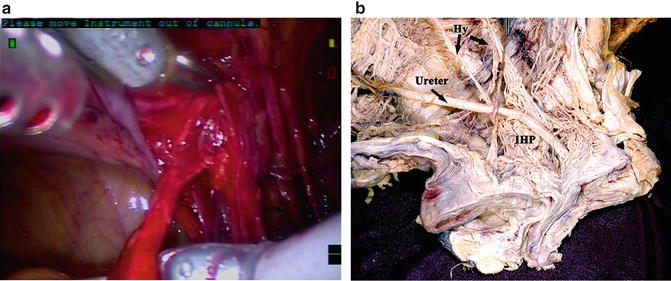

With the posterior peritoneum incised along the ovaries and fallopian tubes, the medial edge of that incised peritoneum is grasped and lifted. The ureter can be found underlying and somewhat adhered to the posterior peritoneum along this medial leaflet. The ureter is encircled and the ureter is bluntly and sharply dissected distally down towards the level of the bladder (Fig. 7.3a). One should avoid grasping the ureter with the robotic instruments to avoid crush injury and resultant devascularization to the ureter itself. As one approaches the bladder they will encounter the uterine vasculature crossing lateral to medial towards the level of the cervix. Overly aggressive distal dissection in this area can result in bleeding as well as inadvertant damage to pelvic splanchnic nerves supplying portions of the vagina. Careful meticulous dissection in this area will identify the uterine vessels traveling just superficial to the ureter as they branch at the junction of the cervix and the vagina to form ascending and descending perforators to both structures. These uterine vessels (a.k.a the ventral vesicouterine ligament) can be isolated from the dorsally located ureter and transected with electrocautery. The ureter can easily be ligated at this point in most instances with adequate length for subsequent diversion. Hemolock clips (if desired a suture can be secured to the clips for the ureter as a tag for later identification) are used to ligate the ureters and they are divided at this level on each side. The transected ureters are tucked into the upper quadrants away from the pelvic dissection. If extra length on the ureters is desired, careful dissection posterior to the ureter at this level is mandatory, as the surgeon will encounter the vaginal artery and inferior hypogastric nerves. The nerves are located lateral and posterior to the ureter at the level of the uterine artery and ureter crossing in the dorsal vesicouterine ligament [8]. As the ureter enters the bladder, there is an avascular space just posterior to the ureter that can be widened with blunt dissection. Retraction of the ureter lateral and ventral will expose the dorsal vesicouterine ligaments, with its enclosed nerves, and prevent their transection. In general this extra ureteral length is not required. However, knowledge of the anatomy here will prevent transection of these nerves especially when dissecting lateral to the vagina at this level or if partial vaginectomy is required for proper surgical margins of the bladder (Fig. 7.3b).

Fig. 7.3

(a) identification and dissection of ureters (b) Anatomic relationship between distal ureter and inferior hypogastric plexus. Photo used with permission by Keiichi Akita, Professor Clinical Anatomy, Tokyo Medical and Dental University

Posterior Bladder Dissection

The peritoneum is incised between the level of the uterus and vagina (posteriorly) and the bladder (anteriorly): this incision can be made right at the level of the peritoneal reflection. With this lateral (“east to west”) incision made, the plane between the bladder and the vagina can be developed bluntly. With the uterine manipulator or a vaginal sponge stick in place, the dissection is carried along the vaginal wall to create an adequate wide margin on the level of the posterior bladder wall. In cases where a vaginal-sparing procedure is anticipated, this dissection can be taken down to the level of the bladder neck and urethra preserving the underlying arcus tendinous pelvic fascia (ATPF) The levator fascia, covering the levator ani complex, as it descends medially attaches to the arcus tendinous pelvic fascia (ATPF). The ATPF is composed of the pubocervical fascia, lying between the bladder and the vagina, as well as the rectovaginal septum. These structures are connected to one another as this fascial complex runs laterally to medially [19]. The preservation of this structure is important in nerve-sparing cystectomy as hstiologic studies have identiifed numerous sympthatic and parasympathetic nerve fibers within this mesh-like structure. This fascial plane also acts as a support structure and therfore preservation may decrease occurrence of pelvic organ prolapse and improve voiding patterns in orthotopic diversions [20]. However, as discussed in later sections, this fascial plane is difficult to distinguish as one reaches the level of the proximal urethra, and the muscular component of the anterior vaginal wall can contribute significantly to the posterior urethra at this level. If any aspect of the anterior vaginal wall is to be removed, the vagina can be entered and the anterior vaginal wall taken en bloc with the bladder thus creating the plane of dissection within the vagina itself.

Lateral Dissection

The peritoneum is incised just lateral to the medial umbilical ligaments on each side. This incision is carried laterally along side the bladder and extending posteriorly to the previously made peritoneal incisions overlying the ureter and between the bladder and uterus/vagina. (Of note the urachal and medial umbilical attachments are left intact to help suspend the bladder and facilitates the posterior and lateral dissection and the stapling of the bladder pedicles.) Blunt dissection can be used to develop the lateral perivesical space without much difficulty down to the level of the endopelvic fascia. In a non-orthotopic diversion or non-nerve-sparing procedure, the endopelvic fascia can be incised at this point. The lateral vascular pedicles of the bladder including the superior vesical artery can now be readily visualized.

Securing Bladder Pedicles

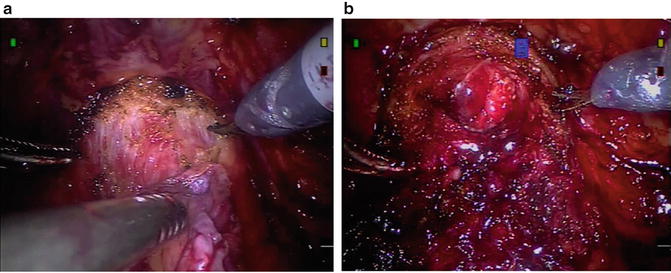

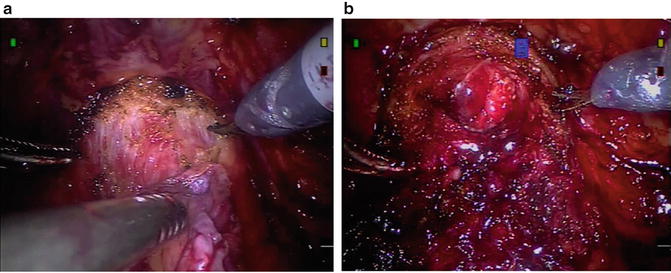

A laparoscopic endovascular stapler is used to ligate and transect the vascular pedicles to the bladder (Fig. 7.4a, b). Usually a single fire of a 60-mm stapler/cutter is sufficient to secure the bladder pedicles on each side. Alternatively these pedicles can be secured using the bipolar cautery or with the use of hemolock clips and then sharply divided. In cases where the anterior vaginal wall is to be taken en bloc with the bladder, the posterior plane of this dissection can be within the vagina itself—as opposed to between the bladder and vagina in a vaginal-sparing procedure. Vaginal entry can result in loss of pneumoperitoneum. To maintain insufflation pressure a moist laparotomy pad or large occlusive dressing (e.g., Tegaderm dressing, 3M Corp., St Paul, MN) is used to occlude the vaginal outlet and prevent loss of pneumoperitoneum.

Fig. 7.4

Placement of endovascular stapler to divide pedicles (a) and image of divided bladder pedicle (b)

Anterior Dissection

With the posterior and lateral dissections complete, attention is then turned anteriorly. The peritoneum is incised anteriorly through the medial umbilical ligament and the urachus thereby “dropping” the bladder. The anterior prevesical space is bluntly developed down to the level of the pubis and exposing the endopelvic fascia on each side. In an orthotopic diversion the endopelvic fascia is left intact to avoid any perturbance of the underlying continence mechanism in the female. In a non-orthotopic diversion the endopelvic fascia is incised, as noted previously, to allow for complete distal dissection of the bladder neck and urethra.

Bladder Neck/Urethral Dissection

The bladder neck is then approached anteriorly. In an orthotopic diversion, great care is made to create this transection precisely at the level of the bladder neck (Fig. 7.5a). Careful and continued evaluation at the location of the bladder neck is performed with the Foley catheter balloon in place to help visualize and identify the bladder neck. For this portion of the procedure the surgeon must carefully consider the competing interests of a sound cancer operation and functional preservation for the best quality of life postsurgically. However the clinican must remember that the foremost concern is for removal of cancerous tissue. Therefore the appropriate disseciton must be a case-by-case decision. In this context it is important to note that a functional and anatomical dissection can be achieved. Several principles are important to consider in regards to functional outcome: the preservation of the ATPF, maximizing urethral length, and preservation of lateral peri-urethral tissue. The first of these, ATPF preservation has been previously described in the section on posterior bladder dissection.

Fig. 7.5

Transection of urethra at the level of the bladder neck (a) in an orthotopic diversion. The bladder neck–urethral junction can be visualized and confirmed with catheter movement. Adequate urethral length remains after transection (b)

The contribution that urethral length provides for continence is debated; however, many urologists feel that both urethral length and closing urethral pressure are important considerations in female continence. Animal studies have shown that in a denervated urethra that closing urethral pressure is markedly decreased, therefore urethral length could be increasingly important in this situation [20]. This would argue for transection of the urethra as close to the bladder neck as possible.

However the composition of the posterior urethral wall is varied and has been shown, in cadaveric studies, to include significant contributions from the detrusor muscle in some cases [19]. It is therefore important that the clinician is mindful of this when completing the bladder neck dissection for the orthotopic diversion. Authors have advocated urethral transection as close as 5 mm to the bladder neck to around 1 cm, however, the decision is obviously a balance between sound oncologic principles and functional preservation and must be made at the time of dissection. Also the urethral margin that is performed for frozen section, if orthotopic diversion is desired, should make sure to include a portion of the posterior urethra based on anatomic and histologic studies.

The most common histologic appearance of the posterior urethra shows significant contribution from the anterior vaginal wall [19]. This makes a combined approach to the urethra ideal in our experience. The posterior plane dissection, as described above, significantly aids in delineation of the posterior plane up to the level of the bladder neck and posterior urethra. Then once the bladder is released from its peritoneal attachments the urethra can be isolated with an anterior approach.

The preservation of the lateral peri-urethral tissues is not dissimilar to the dissection that is carried out in the male patient. This tissue contains the perineal membrane, a U-shaped structure at the level of the mid urethra. This supporting structure consisting of collagen and elastic fibers and runs from the anterior mid urethra posterio lateral to the vagina and terminates at the level of the perineal body. This structure is felt to provide support for the urethra and contains in its lateral portion abundant nervous tissue. The cavernous nerves that supply innervation to the vaginal vestibule and vestibular glands runs through the ATPF on the posteriolateral side of the vagina and as it runs more superficial penetrates and runs on the lateral portion of the perineal membrane to supply these structures. Therefore protection of this tissue and medial dissection of the urethra and perineal membrane will aid in sexual preservation for the patient [19].

In the non-orthotopic diversion, the urethra can be dissected quite distally. When a complete urethrectomy is desired, we circumferentially incise the urethra at the beginning of the case before docking the robot. Bovie electrocautery on cutting current can help release the urethra from the vaginal mucosa and allow for a more complete urethrectomy when approached transperitoneally with the robotic dissection. Before transecting or delivering the urethra, we will typically place an extra large hemolock clip on the bladder (specimen) side to avoid any urine spillage.

After urethral transection, some remaining posterior lateral attachments will remain and these can often be divided with blunt and sharp dissection and with the use of monopolar and bipolar cautery. If the anterior vaginal wall has been incised en bloc, the entire bladder and anterior vaginal wall specimen can be removed through the vagina or placed in an impermeable bag.

Specimen Retrieval

In cases of an orthotopic diversion after the bladder neck has been transected at the appropriate level, the Foley catheter is left in place and the remainder of the bladder specimen is completely freed dividing any remaining posterior–lateral attachments. The catheter is clipped with an extra large hemolock (to avoid any urinary spillage and contamination), the Foley is transected, and the cut end is brought into the pelvis (Fig. 7.6a). The specimen is then placed in an impermeable retrievable bag that is moved out of the pelvis (Fig. 7.6b). The pelvis is irrigated, vaginal surface inspected, and hemostasis ensured. A urethral margin is sent for frozen section evaluation.