7 Repair of the Posterior Vaginal Compartment

To view the videos discussed in this chapter, please go to expertconsult.com. To access your account, look for your activation instructions on the inside front cover of this book.

7-1 Defect-Specific Rectocele Repair

7-2 Rectocele Repair in Conjunction With Repair of Posterior Enterocele

7-3 Biological Mesh Augmentation of Repair of Recurrent High Rectocele

7-4 Site-Specific Rectocele Repair in Conjunction With Overlapping Sphincteroplasty

7-5 End-to-End Anal Sphincter Repair in Conjunction With Extensive Perineoplasty

Posterior compartment prolapse involves herniation of the small intestine and/or rectum into the posterior vaginal compartment, which extends from the cervix or vaginal cuff to the perineal body and includes the anal sphincter. Symptomatic isolated posterior compartment defects are relatively unusual and are seen most often in women who sustained severe posterior tears in association with vaginal delivery or in women who have previously undergone repair of the anterior or apical compartment. More frequently, posterior compartment defects are associated with more global pelvic floor dysfunction and vaginal prolapse. Many factors, including childbirth, aging, estrogen withdrawal, habitual abdominal straining, and heavy labor, weaken the pelvic floor and its associated support structures. Childbirth can cause stretching of the prerectal and pararectal fasciae with detachment of the prerectal fascia from the perineal body, which allows rectocele formation. In addition, vaginal childbirth damages and weakens the levator musculature and its fascia, which attenuates the decussating prerectal levator fibers and the attachment of the levator ani to the central tendon of the perineum. The result is a convex sagging of the levator plate with a loss of the normal horizontal vaginal axis. The vagina becomes rotated downward and posteriorly, no longer providing horizontal support. These anatomical changes allow downward herniation of the pelvic organs along this new vaginal axis. Enterocele formation is caused by transmission of intraabdominal pressure to the pouch of Douglas, with herniation of small intestine along the rectovaginal septum. Widening of the anogenital hiatus and damage to the urogenital diaphragm and central tendon further facilitate pelvic prolapse by preventing the normal compensatory narrowing of the vaginal opening. Varying degrees of perineal trauma and tears contribute to widening of the vaginal introitus. The repair of the relaxed or disrupted perineum and the repair of a rectocele are two distinct operative procedures, although they are often performed together.

Surgical Anatomy

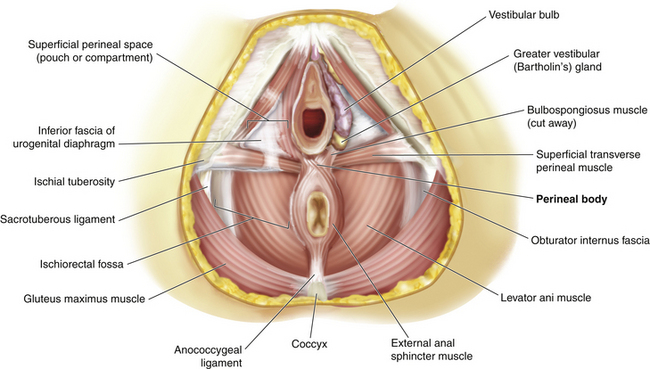

Several structures provide support for the posterior vagina and rectum:

1. The rectovaginal septum lies between the rectum and the vagina. It extends caudad from the posterior cervix and the uterosacral-cardinal complex to the perineal body centrally and the levator fascia laterally on each side. The rectovaginal septum is densest distally where it is composed of dense connective tissue. Its midportion contains fibrous tissue, fat, and neurovascular tissue. Proximally it is mostly composed of fat cells.

2. The pararectal “fascia” lies between the rectovaginal septum and the rectum. It originates from the pelvic sidewalls and divides into fibrous anterior and posterior sheaths, which envelop the rectum. It also contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymph nodes that supply the rectum.

3. The levator ani consists of the paired ileococcygeus, puborectalis, and pubococcygeus muscles. These function to maintain constant basal tone and a closed urogenital hiatus. They also provide a reflex contraction in response to increases in intraabdominal pressure. The puborectalis muscle acts as a sort of sling that causes the posterior vaginal wall to angulate about 45 degrees from the vertical.

4. The perineal body is the central point between the urogenital and anal triangles (Fig. 7-1). It contains interlacing muscle fibers from the bulbospongiosus and superficial transverse perineal muscles and the anterior portion of the external anal sphincter. There is also a contribution from the longitudinal rectal muscle and the medial fibers of the puborectalis muscle.

Several critical components of pelvic floor relaxation are associated with rectocele formation. Loss of the normal horizontal axis of the levator plate and vagina, weakness of the urogenital and pelvic floor diaphragms, detachment of the levator ani from the central tendon of the perineum, and widening of the anogenital hiatus allow intraabdominal forces to be transmitted directly to pelvic organs without counteraction by normal underlying compensatory mechanisms. In addition, the rectovaginal septum becomes attenuated or disrupted, which allows intravaginal herniation of the rectum. Isolated breaks in the rectovaginal septum facilitate rectocele formation. There are several areas along the rectovaginal septum where breaks are commonly found (Fig. 7-2). The most common is a transverse separation immediately above the attachment of this septum to the perineal body, which results in a low or distal rectocele (seen just inside the introitus). A midline vertical defect is also very common and most likely represents a poorly repaired or poorly healed episiotomy. Rarely, one can see lateral separation on one side. Defects can occur in isolation or in combination. Identification of specific defects is important when one is considering performing a site-specific posterior repair. Therefore, each of these components of pelvic floor relaxation must be addressed at the time of rectocele or posterior vaginal wall repair. Identification of the specific pathophysiological features is critical when one is evaluating female patients with symptoms or signs of pelvic floor relaxation, including stress incontinence, cystocele, and/or uterine prolapse. Maintenance of the normal horizontal vaginal axis to allow compensatory mechanisms to be reestablished is an important goal of surgical repair of pelvic floor relaxation. Corrective surgery for posterior vaginal wall prolapse may include correction of the rectocele by reinforcement of the rectovaginal septum and prerectal and pararectal fasciae, repair of the levator muscle defect to restore the levator hiatus, restoration of the horizontal supporting plate of the proximal vagina, and repair of the perineum.

Preoperative Evaluation

Physical Examination

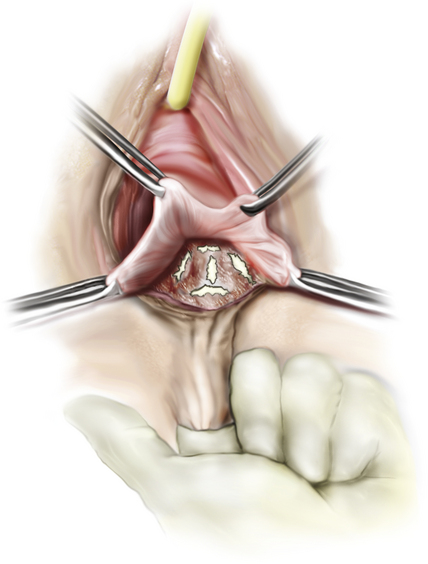

Assessment of the posterior vaginal compartment should be a routine component of the examination of any patient with incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse (see Chapter 1). This includes inspection for the presence of enterocele, rectocele, and perineal weakness. Generally, the posterior compartment is evaluated by displacing the anterior vaginal wall with half of a Graves speculum to allow complete visualization of the posterior wall during straining. Digital examination with one of the examiner’s fingers in the vagina and one finger in the rectum allows assessment of the rectovaginal septum, which is often quite attenuated with Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) stage II and III rectoceles and may contain an enterocele sac. Physical examination may not reliably distinguish an enterocele from a high rectocele. Inspection of the rectovaginal septum for isolated breaks, typically found near its attachment to the perineal body or in the midline, is performed by placing a finger in the rectum and lifting up the posterior vaginal wall. Finally, inspection of the perineal body is performed to identify any defect associated with a widened introitus and a decreased distance between the anus and posterior vaginal fourchette. In cases of severe prolapse, combined defects of posterior vaginal wall support at the level of the pelvic floor and the perineum are often present.

Radiographic Evaluation

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be an adjunct in identifying and quantifying the presence of a rectocele as well as associated pelvic floor dysfunction, pelvic organ abnormality, pelvic organ prolapse, and rectal prolapse and/or intusseption. Specifically, dynamic pelvic MRI can provide objective quantification of prolapse in all three vaginal compartments while also assessing for any underlying urological or gynecological pathological condition. Static images are obtained in both sagittal and parasagittal planes from left to right across the pelvis. Then a set of dynamic images in the midsagittal plane is acquired during the resting and straining states. This particular set of dynamic images is helpful in identifying pelvic floor descent and pelvic organ prolapse. The pubococcygeal line and posterior puborectalis muscle sling are fixed anatomical reference points used to quantify organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Organ prolapse is defined as any protrusion beyond the pubococcygeal line during the dynamic phase with Valsalva maneuvers. A rectocele is easily identified when the rectum is filled with gas, fluid, or gel. Furthermore, gel can be instilled rectally to perform magnetic resonance (MR) defecography and identify specific areas of rectovaginal septum attenuation, rectal mucosal prolapse or intussusception, and defects of the anal sphincter and perineal body. Dynamic pelvic MRI in conjunction with MR defecography can be especially useful in evaluating for rectocele, enterocele, and internal or external rectal prolapse. The findings can help in surgical planning by both the female pelvic reconstructive surgeon and the colorectal surgeon.