8 Repair of Pelvic Organ Prolapse Using Synthetic Mesh Kits

To view the videos discussed in this chapter, please go to expertconsult.com. To access your account, look for your activation instructions on the inside front cover of this book.

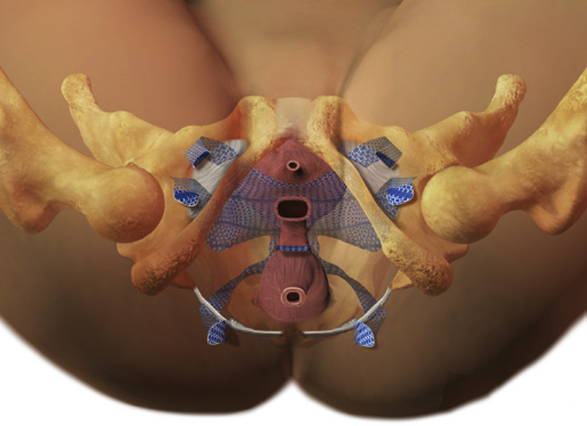

In this chapter, we discuss the mesh kits currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in prolapse repair. These include mesh overlay kits containing customizable sheets of mesh that the surgeon fashions intraoperatively into implants of the appropriate shape and size and places over the prolapsed tissue; trocar-based anterior and posterior synthetic mesh kits; and trocarless, or direct-access, synthetic mesh kits. In general, mesh kits aim to provide apical support as well as anterior and posterior vault support through anchoring to structures such as the coccygeus muscle–sacrospinous ligament (C-SSL) complex, the obturator membrane, and levator and inner thigh muscles. It is critical to thoroughly understand the anatomy and the proper sites for anchoring these mesh implants to ensure a safe and successful anatomical and functional repair. Because of this, we also discuss the appropriate anatomical landmarks, proper placement of anchoring devices or sutures, proper tensioning of the synthetic materials, and potential complications associated with these products.

Editor’s note: Permanent synthetic mesh grafts have unique complications, including vaginal extrusion, urinary tract erosion, and infection. These risks must be carefully weighed against the potential benefits. In July 2011, the FDA issued a notification regarding the use of transvaginal synthetic mesh for the repair of POP.*

Finding the Ideal Mesh

Surgeons must also keep in mind the ideal characteristics of candidates for synthetic mesh placement. Generally, patients who have risk factors associated with poor healing or who have had complications after previous mesh procedures should not be offered augmentation with a mesh kit. Patients with severe genital atrophy, a history of radiation therapy, or baseline chronic pelvic pain may experience more postoperative complications after mesh placement. In addition, patients who desire to maintain sexual function should be informed that mesh augmentation may cause some loss of elasticity, which can lead to dyspareunia in either partner. Ensuring that the patient thoroughly understands the benefits and potential risks of synthetic mesh–augmented pelvic organ prolapse procedures is an essential part of the consent process. The potential risks must be weighed against the perceived advantage of better durability with mesh augmentation.

• Surgeons should undergo rigorous training covering the principles of pelvic anatomy and pelvic surgery as well as instruction on proper patient selection for pelvic organ prolapse reconstructive procedures. Such training must be completed before implantation of surgical mesh is attempted for the treatment of prolapse.

• Before using mesh in pelvic floor repair, surgeons should be properly trained in specific mesh implantation techniques.

• Before implantation of mesh, surgeons should be competent in recognizing intraoperative and postoperative complications as well as comfortably and completely managing these adverse events. Such adverse events include those involving the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts.

• Before implantation of surgical mesh for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse, the surgeon and patient must have a proper informed consent discussion regarding the risks, benefits, alternatives, and indications for the use of mesh.

Trocar-Based Mesh Kits

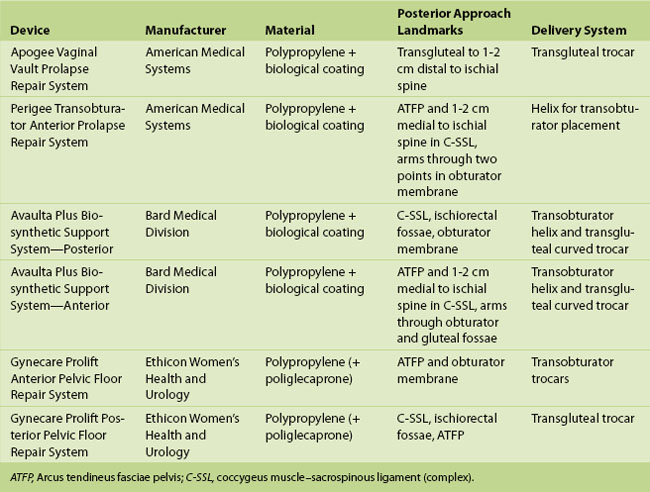

Several FDA-approved trocar-based kits are available for both anterior and posterior approaches to repair of pelvic organ prolapse (Fig. 8-1, Box 8-1, and Table 8-1). All of the available trocar-based devices use the C-SSL complex for apical support. The obturator membrane is used as a distal anchor by the majority of anterior kits, with the superior arms placed in much the same way as a transobturator midurethral sling and the inferior arms passed through an avascular portion of the obturator membrane and through the ischiococcygeus complex overlying the sacrospinous ligament.

Figure 8-1 Gynecare Prolift total repair system.

(Courtesy Ethicon Women’s Health and Urology, Somerville, NJ.)

Box 8-1 Elements Necessary for Appropriate Use of Pelvic Mesh Kits

• Full-thickness dissection of the anterior or posterior vault to prevent erosion after surgery

• Tension-free placement and adjustment of all mesh materials to account for up to 25% contraction occurs over time

• Adequate distancing of mesh arms to avoid rolling or bunching of synthetic materials

• Cystoscopy and rectal examination before closure to ensure that no mesh or arms are in the urethra, bladder, or rectum

• Minimal or no trimming of the vaginal epithelium to allow for contraction of the mesh without potential shortening or narrowing of the vagina

Posterior approach devices are designed to correct apical and posterior vaginal wall defects. They also use the C-SSL complex for apical suspension via a posterior and extraperitoneal approach with the trocars introduced pararectally in the gluteal fossae.

Surgical Technique for Anterior Trocar-Based Mesh Kits

All patients should receive antibiotics perioperatively, have a Foley catheter inserted, and be placed in the dorsal lithotomy position. Thromboembolic precautions should also be taken during and after anesthesia. We recommend that the vaginal epithelium be well estrogenized before these procedures when possible and routinely prescribe the use of vaginal estrogen cream before and after surgery to optimize tissue condition. Procedures for using several of the available mesh kits are described; however, we stress again that surgeons should be appropriately trained in the specific procedure they are performing in keeping with the FDA recommendations cited previously.

Anterior Gynecare Prolift System

1. For repair using the Gynecare Prolift Anterior Pelvic Floor Repair System (Ethicon Women’s Health and Urology, Somerville, NJ), the procedure begins with hydrodissection of the anterior vaginal wall using anesthetic and epinephrine to a level of 1 to 2 cm above the cuff or cervix.

2. A vertical incision is made full thickness through the epithelium and underlying vesicovaginal fascia and into the true vesicovaginal space. Use of this dissection plane allows the mesh to be placed with a thicker layer of tissue (generally 5 to 7 mm) between the mesh and vaginal vault. The desired plane is often described as a glossy, gray, gelatinous-appearing area that may have some perivesical adipose tissue within it. Anatomically, proper hydrodissection and careful identification of the vesicovaginal plane are essential for repair.

3. Dissection with Metzenbaum scissors to the superior pubic rami can be accomplished by keeping the scissors parallel to the vaginal epithelium and pointing toward the ipsilateral shoulder.

4. Once this level of lateral dissection is obtained, blunt dissection of the paravaginal space until all areolar connective tissue is freed allows excellent palpation of the ischial spines and palpation medially to the C-SSL complex.

5. The Prolift kit uses two anchoring arms that pass through two sites in the inferior portion of the obturator foramen to avoid the neurovascular supply in the superior portion of the membrane. Before the trocars are passed, the proposed entry sites are marked and infiltrated with the surgeon’s choice of local anesthetic. The superior incision in the groin is identical to that used in transobturator sling procedures and can be marked in the superior medial notch just below the adductor longus tendon in the midclitoral line.

6. The inferior incision is made 1 cm lateral and 2 cm inferior to the superior incision to allow passage of a second trocar through the inferolateral portion of the membrane. The inferior trocar with cannula is placed in a trajectory that penetrates the obturator membrane toward the ischial spine.

7. Once the spine is reached, the trocar handle is elevated and advanced into the iliococcygeal fascia and then into the dissected paravaginal space. The cannula is then left in place as the trocar is removed.

8. The superior trocar is passed in an out-to-in fashion following the curve of the pelvis after initial penetration of the obturator membrane. The cannula is similarly left in the dissected paravaginal space, and the trocar is removed.

9. Once the cannulae are in place, it is important to confirm that the distance between them is great enough to avoid bunching of a properly sized piece of mesh. Generally, this distance is estimated to be 5 cm or greater.

10. The mesh is appropriately trimmed to the specific size of material needed by measuring the distance from the junction of the bladder neck and the apex, whether it is the cervix or the vaginal cuff. The mesh is tacked in place with 2-0 delayed absorbable suture at the level of the bladder neck and the cuff or cervical stroma.

11. The mesh arms are then fed through the cannulae and appropriately adjusted to achieve good apical suspension that does not cause bunching or excessive tension on the mesh.