4 Repair of Anterior Vaginal Prolapse

To view the videos discussed in this chapter, please go to expertconsult.com. To access your account, look for your activation instructions on the inside front cover of this book.

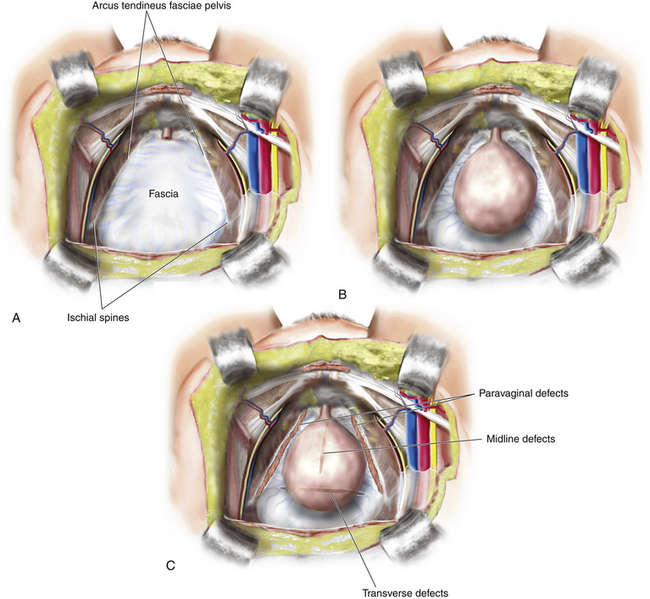

Anterior vaginal wall prolapse, commonly termed cystocele, is defined as pathological descent of the anterior vaginal wall overlying the bladder base. Cystoceles frequently coexist with a variety of micturition disorders. The current understanding of the anatomy and support of this segment of the pelvic floor stems from concepts proposed by Richardson et al., who described transverse, midline, and paravaginal defects. Transverse defects are said to occur when the pubocervical fascia separates from its insertion around the cervix, whereas midline defects represent an anterior-posterior separation of the fascia between the bladder and the vagina, and paravaginal defects are characterized by detachment of the lateral connective tissue attachments at the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis (ATFP). A conceptual representation of these various defects is shown in Figure 4-1. All types of micturition disorders can be seen with anterior vaginal wall prolapse, and to date, there is no clear scientific explanation to help in understanding the correlation between anatomical descent of the anterior vaginal wall and functional derangements of the urinary tract. When conducting evaluation and planning for surgical treatment of patients with anterior vaginal wall descent, the surgeon must go to great lengths to determine how the surgical intervention will affect any potential functional derangements that the patient may be experiencing. This aspect of the preoperative discussion with the patient and the patient consent process is extremely important.

Although many surgeons make a great effort to predict preoperatively what types of defects exist when patients have symptomatic anterior wall descent, the literature indicates that this is very difficult to do, and in our opinion determination of the various defects is best done intraoperatively. Thus it is critically important that the surgeon be able to customize the repair to meet the needs of a particular patient’s anatomy. Although numerous types of repairs are discussed and demonstrated here, the ultimate goal of any anterior vaginal wall support procedure is to re-create a trapezoid of support that runs from below the proximal urethra to the cervix or apex and laterally to the ATFP or fascia of the internal obturator muscle. Finally, the long-term success of the anterior vaginal wall repair is directly correlated with the ability to suspend the apex in a high, durable position without creating any significant distortion of the vaginal axis.

• Surgeons should undergo rigorous training covering the principles of pelvic anatomy and pelvic surgery as well as proper patient selection for POP reconstructive procedures. Such training must be completed before implantation of surgical mesh is attempted for the treatment of prolapse.

• Before using mesh in pelvic floor repair, surgeons should be properly trained in specific mesh implantation techniques.

• Before implantation of mesh, surgeons should be competent in recognizing intraoperative and postoperative complications as well as comfortably and completely managing these adverse events. Such adverse events include those involving the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts.

• Before implantation of surgical mesh for the treatment of POP, the surgeon and patient must have a proper informed consent discussion regarding the risks, benefits, alternatives, and indications for the use of mesh.

This chapter describes techniques that can be performed without implants but can be adapted to tissue augmentation with a material if the surgeon so desires. The use of commercially available prolapse mesh kits is discussed in Chapter 8.

In many cases of anterior prolapse, other compartments, especially the apex, need to be corrected. The techniques described here can be used to correct an isolated anterior defect and can also be combined with procedures to restore apical support (see Chapter 6).

Native Tissue Anterior Colporrhaphy

Case #1

View Video 4-1

View Video 4-1

A 55-year-old woman complained of pelvic pressure, a vaginal bulge, and SUI. Physical examination showed Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) stage II anterior prolapse with the leading edge of the prolapse about 0.5 cm beyond the hymen with straining (POP-Q point Ba = −0.5). The uterus and cervix were relatively well supported with the leading edge of the cervix 4 cm above the hymen with straining (point C = −4). The patient was sexually active and concerned about the consequences of implantation of permanent mesh. The defect was found to be predominantly a central defect. An anterior colporrhaphy was performed before placement of a synthetic midurethral sling (Video 4-1).