and Christopher Isles2

(1)

Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK

(2)

Dumfries and Galloway Royal Infirmary, Dumfries, UK

Q1 What do you understand by the term renovascular disease?

Renovascular disease, sometimes referred to as “ischaemic nephropathy” is a term used to describe patients with narrowing of either their main renal (large vessel) or intra-renal (small vessel) arteries or arterioles.

Q2 How does renovascular disease of the main renal arteries present clinically?

A number of clinical presentations are recognised. Large vessel renovascular disease causes problems when one or more of the main renal arteries are stenosed >60 % as this is the degree of stenosis required to reduce blood flow. Hypertension is an important consequence of both unilateral and bilateral renal artery stenosis. AKI is frequently precipitated by ACE inhibitors in patients with previously unsuspected bilateral disease or stenosis to a single kidney. CKD and cardiorenal failure can also occur in patients with bilateral disease or stenosis to a single kidney (Fig. 23.1).

Fig. 23.1

Presentation of large vessel renovascular disease

Q3 How does small vessel renovascular disease present clinically?

Three clinical presentations are recognised. The most common, hypertensive nephrosclerosis, is best thought of as renal artery stenosis affecting the intrarenal arteries. The term malignant hypertension describes a severe form of hypertension with diastolic pressure usually >130 mmHg, bilateral retinal haemorrhages and exudates and/or bilateral papilloedema. The histological hallmark is fibrinoid necrosis of the intrarenal arterioles. Atheroembolism (aka cholesterol embolism) occurs when cholesterol crystals break off from an atheromatous aortic wall to be swept downstream to the kidneys and peripheral vessels. Those that lodge in the kidneys do so in small arterioles where they provoke a fibrotic reaction which eventually occludes the lumen of these vessels causing subacute renal failure (2 or 3 weeks after the insult rather than 2 or 3 days). We report a case below. Diagnosis of atheroembolism can be made without a renal biopsy if the following triad is present:

A precipitating factor such as aortic instrumentation e.g. coronary angiography.

Subacute renal failure (as above).

Peripheral embolisation causing a livedo reticularis over the knees and the so-called purple toe syndrome.

Case Report

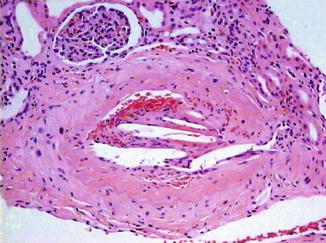

A 66 year old man presented with subacute renal failure, livedo reticularis and purple toes 2 months after coronary angiography. This was on a background of hypertension, previous inferior MI, peripheral vascular disease and an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Renal function had been normal at the time of coronary angiography. Renal biopsy identified elongated bi-convex needle shaped cholesterol crystals occluding the lumen of a small artery (see Fig. 23.2). This patient’s course was complicated by severe acute pancreatitis (a recognised complication of atheroembolism) which led to multi organ failure requiring dialysis, ventilation and inotropic support. He remained dialysis dependent for 35 months before eventually recovering enough renal function to stop renal replacement therapy.

Fig. 23.2

Case report of cholesterol emboli with histological section demonstrating cholesterol emboli within renal arteriole

Cuddy E et al. Risk of coronary angiography. Lancet. 2005;366:182; with permission from Elsevier

Q4 What causes renovascular disease of the main renal arteries?< div class='tao-gold-member'>Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree