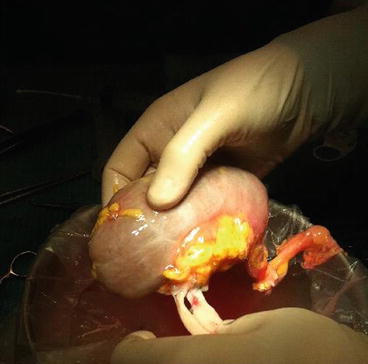

Fig. 16.1

Right kidney in the basin during bench surgery. One of the two renal arteries (RA) has been accidentally sectioned from its origin during the retrieval. Ao aorta, RV renal vein, U ureter, K renal parenchyma

Fig. 16.2

The renal graft once the bench surgery has been completed. The renal artery and the vein have been dissected free of the extra tissue. The paraureteral fat has been preserved as well as the hilar fat

The renal vein and the IVC are dissected free of the extra tissue, and gonadal, adrenal, and any other veins coming from extrarenal tissue are ligated and divided. A similar procedure is performed with the renal artery taking into account that even small branches coming from the main artery are likely to supply the kidney (it is very unusual to find branches which do not go to the parenchyma).

An accurate dissection between ligations is recommended not only to obtain good hemostasis once the clamps in the recipient have been released but also to close lymphatic vessels and to limit the incidence of lymphorrhagia and lymphocele posttransplant [5].

16.1.1 Kidney Preservation

Despite the significant increase in live donor kidney transplantation over the past 20 years, the number of patients awaiting transplant continues to rise [6]. In order to expand the pool of available donors, all the fields of science related to the process of donation/transplantation have been the subject of renewed interest in the last decade. Particular attention has recently been focused on the importance of preservation of grafts, especially of those obtained from marginal donors. Hypothermia allows the cellular metabolism to adapt itself to the anoxy condition (at 4 °C, the metabolism decreases by about 95 %); the drop in the energy consumption is also associated with the reduction of the activity of hydrolytic enzymes (proteases, phospholipases, nucleases) which limits structural cellular damage to the graft. Even if no firm recommendations establish the optimum method of renal preservation [7], some recent reports advocate certain advantages in terms of reduced incidence of delayed graft function and 1-year graft survival of machine perfusion when compared with static cold storage [8–11]. Even if the results of recent studies appear not quite homogenous, there appears to be enough benefit associated with pulsate preservation to justify its continued use in routine clinical practice. A perfusion machine, measuring parameters such as renal resistances, may also offer a prognostic value that, in the near future, together with pathologic and clinical features could become part of the evaluation of the graft and contribute to the allocation process. Further adequately powered randomized studies are required in both heartbeating and non-heartbeating donors, standard criteria donor, and expanded criteria donors using standardized perfusion fluid, in order to estimate the real advantage in specific and homogenous subgroups of donors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree