Renal Pelvic Tumors

Debra L. Zynger

Bladder cancer is common, whereas malignancy of the upper urothelial tract is rare. Within the upper urothelial tract, tumors in the renal pelvis are twice as common as the ureter (1). Ureteroscopy provides excellent visualization of renal pelvic tumors and in conjunction with a tissue biopsy has the potential to provide histologic type, grade, and stage. This chapter addresses renal biopsies obtained via ureteropyeloscopic approach with percutaneous renal procedures discussed in Chapter 1.

PREBIOPSY STUDIES

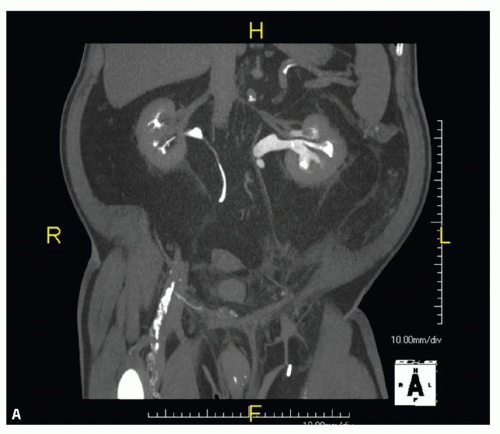

The most common symptom prompting exploration of the upper urothelial tract is gross or microscopic hematuria (2,3,4). Flank pain is the second most common symptom. Previously, the presence of a filling defect on imaging was sufficient for clinical management, whereas now with the development of small caliber flexible endoscopic instrumentation, visualization and sampling of renal pelvic masses are often performed. Computed tomography (CT) urography is the gold standard for the initial evaluation of the upper urothelial tract (1,5,6). The sensitivity for the detection of malignancy approaches 100%, although small polypoid tumors and flat lesions may be missed (7,8). Filling defects that are seen on CT urography may be due to obstruction by a tumor or nontumoral causes including a blood clot, renal calculi, and detached papillae (Fig. 8.1, eFig. 8.1). The diagnosis of a suspected renal pelvic tumor can be confirmed with ureteropyeloscopy.

INDICATIONS

Most endoscopic biopsies of the renal pelvis are performed to evaluate a suspicious imaging filling defect, particularly when imaging is equivocal for malignancy (Table 8.1) (2,9,10). Patients with high-grade urothelial carcinoma may receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy (11). This is especially relevant as post-nephroureterectomy adjuvant chemotherapy is less ideal due to nephrotoxicity and a single remaining kidney (11). Additional indications include surveillance of a previously treated upper tract tumor and positive urine cytology with negative cystoscopy.

BIOPSY TECHNIQUE

A ureteroscope is used to gain access to the renal pelvis and can be inserted through a guidewire or ureteral access sheath (10). Placement of a separate stent (“double J stenting”) may be required to help dilate the ureter or in cases in which the anatomy makes passage of the ureteroscope difficult. Fluoroscopy and direct visual control guide the ascension of the ureteroscope to the renal pelvis. Ureteroscopic procedures may occur with or without tissue biopsy and/or cytology. Flexible ureteroscopes have a greater diagnostic success rate than rigid devises (12). Visualization of abnormal mucosa may be improved in some models via the emission of different wavelengths of light. Tissue is obtained using graspers or baskets. Devises to increase the size of the tissue sample have been created but have to be backloaded, an example of which is the BIGopsy scope (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana) (eFig. 8.2). Tissue samples should be taken as deep as possible for accurate diagnosis and staging; however, this

increases morbidity (10). Urine can be obtained directly from the renal pelvis for cytologic examination by passive collection, saline barbotage, or brushings (13). In addition to obtaining tissue for diagnosis, ureteroscopic treatment (e.g., laser ablation) is possible. As bladder and upper tract tumors can coexist, cystoscopy is also necessary.

increases morbidity (10). Urine can be obtained directly from the renal pelvis for cytologic examination by passive collection, saline barbotage, or brushings (13). In addition to obtaining tissue for diagnosis, ureteroscopic treatment (e.g., laser ablation) is possible. As bladder and upper tract tumors can coexist, cystoscopy is also necessary.

TABLE 8.1 Indications to Perform a Renal Pelvic Biopsy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

COMPLICATIONS

Major complications are not described. The most common side effect of an upper tract endoscopic biopsy is bleeding, followed by ureteral perforation, sometimes requiring a ureteric stent (2,9,14,15,16). Ureter manipulation and perforation is a risk factor for subsequent stricture formation. Concern has been raised regarding high pressure irrigation or tumor manipulation pushing tumor cells into lymphovascular spaces or seeding other parts of the urothelium (17,18). However, there is no greater incidence of lymphovascular invasion in cases with prior ureteroscopy (19). Furthermore, there is no difference in time to recurrence or survival comparing patients with and without diagnostic ureteroscopy (20).

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS

Approximately half of renal pelvic biopsies are diagnosed as urothelial carcinoma (21). Other malignancies of the upper tract detected by endoscopic biopsy are extremely uncommon with rare described instances of diagnosing clear cell renal cell carcinoma, clear cell adenocarcinoma, and tumors of other primary origins (colon, breast, gastric) (21,22,23).

DIAGNOSTIC ACCURACY

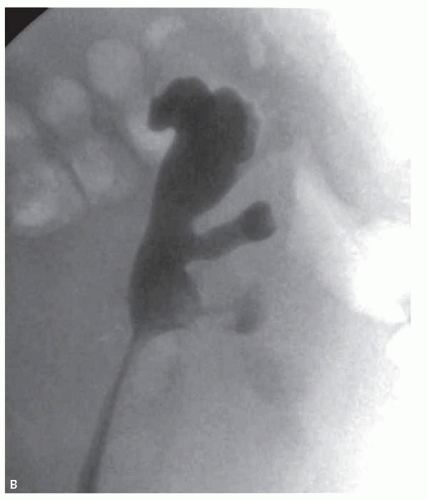

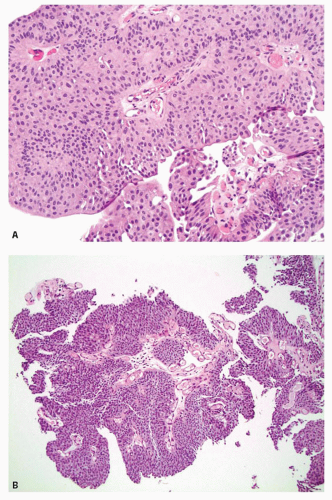

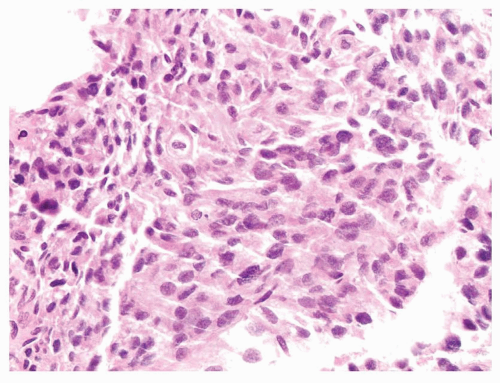

Pathologic diagnostic information is crucial toward determining the appropriate treatment for renal pelvic disease. Renal pelvic primary tumors are managed by nephroureterectomy with bladder cuff excision except in select patients with poor renal function or small, low-grade disease that can be treated with endoscopic ablation (Fig. 8.2) (24,25). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be used in patients with high-volume or high-grade tumor (Fig. 8.3) (11). Unfortunately, the tissue obtained from upper tract biopsies is often minimal and thus suboptimal for diagnosis, grading, and staging (Figs. 8.4 and 8.5). It is critical for the pathologist to understand the diagnostic limitations and pitfalls when evaluating renal pelvic biopsies.

There is a paucity of information regarding the accuracy of endoscopic renal pelvic biopsies, summarized in Table 8.2. One investigation at our tertiary academic medical center found a diagnostic accuracy of 98% for the upper urothelial tract and 100% for the renal pelvis, as the only diagnostic errors were in the ureteral specimens (21). The ureteral misdiagnoses included failing to diagnose urothelial carcinoma in situ and low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. The sensitivity of a renal pelvic endoscopic biopsy was reported to be 78%, with most authors describing errors mainly due to tissue sampling rather than diagnostic errors as the cause of the decreased sensitivity (21,23). As such, negative biopsies may not be representative of the lesion and a repeat biopsy or further treatment

without a tissue diagnosis may be indicated. A specificity of 100% was calculated, suggesting that a malignant diagnosis is highly accurate (21). However, other authors have noted false positive biopsy diagnoses due to overinterpretation of epithelial hyperplasia, detached pieces of urothelium imitating papillary formation, urothelium displaying pseudopapillary formation, or von Brunn’s nest proliferations (Fig. 8.6) (4,16,22). Unless the findings are unequivocal, the diagnosis of malignancy should not be rendered, as this may result in an unnecessary nephroureterectomy. Correlation with endoscopic findings prior to diagnosis is recommended.

without a tissue diagnosis may be indicated. A specificity of 100% was calculated, suggesting that a malignant diagnosis is highly accurate (21). However, other authors have noted false positive biopsy diagnoses due to overinterpretation of epithelial hyperplasia, detached pieces of urothelium imitating papillary formation, urothelium displaying pseudopapillary formation, or von Brunn’s nest proliferations (Fig. 8.6) (4,16,22). Unless the findings are unequivocal, the diagnosis of malignancy should not be rendered, as this may result in an unnecessary nephroureterectomy. Correlation with endoscopic findings prior to diagnosis is recommended.

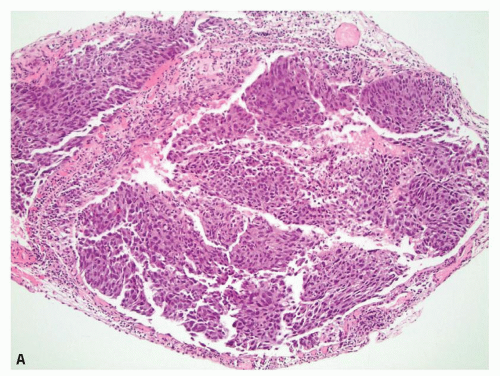

FIGURE 8.4 Urothelial carcinoma in situ/noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma, high grade diagnosed in the renal pelvis. A: Crush artifact makes the growth pattern difficult to discern. B:

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|