22 Rectal/perianal mass and colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cause of cancer mortality in most developed countries. Screening and early endoscopic intervention form the crux of management strategy.

Rectal or Perianal Mass

There are three ways a patient with a perianal or rectal mass may present:

The causes of a lump in the rectum are listed in Box 22.1.

History

Establish when the lump was first recognised and whether it has changed over time. An intermittent nature suggests that the lump relates to prolapse of a lesion from the rectum (e.g. haemorrhoids or rectal prolapse). Determine if the lump could be manually reduced when the lump is external to the anus. Haemorrhoids are a classic example of a potentially reducible lump, but the differential diagnosis includes rectal prolapse and hypertrophied anal papilla. An acute time course favours conditions such as thrombosed internal or external haemorrhoids. Tenderness suggests an infective process such as an ischiorectal abscess (Chapter 12).

Another key symptom is rectal bleeding. Never ignore rectal bleeding and never assume it has a benign cause; bleeding should raise the suspicion of colorectal cancer. Ask about a family history of gastrointestinal disease and, in particular, colon cancer or polyps. Less commonly, a solitary rectal ulcer secondary to prolapse of the rectum can cause bleeding and tenesmus. The passage of mucus may occur with benign or malignant tumours as well as ulceration. Systemic symptoms such as weight loss (e.g. with malignancy) or fever (e.g. with an abscess) may also help point towards the correct diagnosis. A history of menstrual bleeding associated with a tender lump may suggest a perineal endometrial deposit that rarely occurs.

Physical examination

Inspection

Careful inspection is crucial (see Chapter 12) but, importantly, one must expect to find an abnormality. Place the patient in the left lateral position with the buttocks well over the edge of the couch. Part the buttocks, looking for perianal skin tags, which may be associated with pruritus due to suboptimal hygiene. These are usually haemorrhoidal remnants, but they can occasionally be an indicator of a systemic process such as Crohn’s disease (Chapter 15). A perianal haematoma may be visible, which is usually small (under 1 cm). Rectal prolapse can occur at any age; suspect this if the anus is patulous or gaping. Ask the patient to strain; perineal descent may be seen and sometimes rectal prolapse (circumferential folds of red mucosa) may be demonstrated.

Sigmoidoscopy and proctoscopy

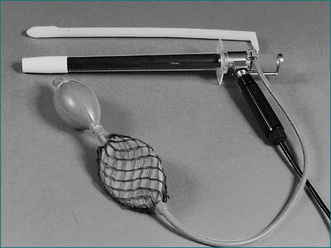

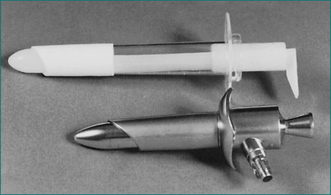

The examination is most commonly performed with the patient in the left lateral decubitus position. In some centres, particularly those equipped with specialised tables, the examination is performed with the patient in the jack-knife position resting on the knees. Usually, adequate clinical information can be achieved without rectal preparation. When the rectum is totally loaded, it can be cleared by inserting an enema; full mechanical bowel preparation is not needed for this examination. Most patients will be anxious about proctoscopy or sigmoidoscopy. They need not see the instrument (Figs 22.1 and 22.2). The examiner needs to reassure the patient, pointing out that the diameter of the instrument is less than the diameter of a large stool and that the examination will be discontinued if there is excessive discomfort.

Tumours of the Colon and Rectum

History

The classic right-sided colon cancer is soft, protuberant and located where the lumen is large and the contents semisolid; anaemia is therefore more likely than obstruction. The classic left-sided colon cancer is annular, stenosing and located where the lumen is narrow and contents are firm; consequently, obstruction is more likely (Fig 22.3). Cancers may form a fistula into the bladder or elsewhere. Advanced cancers may be asymptomatic, while a very early caecal cancer may occasionally present with appendicitis, having obstructed the appendiceal opening.

Rarely, infective endocarditis caused by Streptococcus bovis or Clostridium septicus is the first manifestation of colon cancer.

Physical examination

The rectum may be evaluated with a rigid ‘sigmoidoscope’—a misnomer in that the sigmoid is not adequately seen with this 30-cm instrument. Full evaluation of the colon is necessary with a colonoscopy to identify any tumours (Fig 22.3) and to rule out synchronous cancers. The bowel must be prepared (emptied of all stool) to see the wall clearly. Colonoscopy has the advantage of allowing biopsies and/or therapeutic intervention, and the disadvantage that it can cause rare bowel perforation.

Investigation

Diagnosis is made on the basis of history, physical examination and special investigation (Table 22.1).

Table 22.1 Preoperative assessment of patients with colorectal carcinoma

| Investigation | Comment |

|---|---|

| Blood count, electrolytes, creatinine and liver function tests | Results probably will be normal; useful base-line assessment if major surgery planned |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) | |

| Chest x-ray | Useful—not necessary if patient is healthy or if CT chest is contemplated together with the CT abdomen/pelvis |

| Colonoscopy with biopsy of tumour | Essential unless patient presents acutely with bowel obstruction/perforation |

| Abdominopelvic CT | Essential especially if a laparoscopic colectomy is being considered |

| Transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS) | Essential for staging of rectal cancer which determines the course of management |

Note: Intravenous pyelogram, abdominal ultrasound and MRI may be indicated in special circumstances.

Preoperative investigations should include a full blood count, electrolyte tests and liver function tests. Baseline carcinoembryonic antigen can be sought to aid follow-up, although the benefit of this is controversial (Ch 17). A chest x‑ray examination may detect metastatic disease. If advanced disease is suspected, computed tomography (CT) scanning of the abdomen may be useful; surgery may still be needed for palliation.