Rectal prolapse continues to be problematic for both patients and surgeons alike, in part because of increased recurrence rates despite several well-described operations. Patients should be aware that although the prolapse will resolve with operative therapy, functional results may continue to be problematic. This article describes the recommended evaluation, role of adjunctive testing, and outcomes associated with both perineal and abdominal approaches.

Key points

- •

Rectal prolapse affects patients of both genders and all ages.

- •

A detailed history and physical examination is paramount, with attention on risk factors for underlying disease, functional problems with fecal incontinence or constipation, as well as a complete evaluation for concomitant defects that may need to be addressed at the time or following repair of the prolapse.

- •

Adjunctive testing is not often required, other than in patients with significant constipation or incontinence, and those with risk factors for other diseases (ie, colonoscopy in an appropriate patient).

- •

The mainstay of operative therapy involves both transabdominal and perineal techniques (via open and minimally invasive approaches), and may include fixation through sutures, tacks, or mesh. In general, transabdominal repairs are associated with lower recurrence rates, and transperineal ones are reserved for those at high risk with multiple comorbidities.

- •

Patients should be counseled that their functional problems may or may not improve, even following successful repair.

A video of robotic assisted rectopexy accompanies this article at http://www.gastro.theclinics.com

Rectal prolapse (ie, procidentia) is the full-thickness intussusception of the rectum through the anus ( Fig. 1 ). This condition is distinguished from internal intussusception in that it is more akin to telescoping of the bowel on itself without expression through the anal verge. In addition, it is delineated from mucosal prolapse, in which only the mucosa prolapses through the anal canal, classically with visualization of the radial folds. Full-thickness rectal prolapse is a socially debilitating condition that is associated with bleeding, constipation, fecal soilage, and incontinence. It is part of the spectrum of disorders caused by weakening of the pelvic floor, and often occurs in conjunction with one or more of the other disorders in the spectrum. Despite the multitude of operations described through the years for this common condition, surgical repair is still often plagued by higher than expected recurrence rates and wide-ranging improvements in functional outcomes. This article reviews the data for the operative repair of full-thickness rectal prolapse.

Epidemiology

Although rectal prolapse is thought by many to be a disease of the elderly, procidentia has a bimodal age distribution with peaks at the extremes of age. It can occur at any stage in life. In children it is most commonly diagnosed before 3 years, and is seen more often in boys. Rectal prolapse in adults generally occurs after the fifth decade and is associated with the female gender 80% to 90% of the time. The condition occurs infrequently, with an incidence in adults between 0.25 and 0.42% and a prevalence of 1% in adults more than 65 years of age. Despite this seemingly low number, it is a common condition evaluated by health care providers of all specialties, and especially those treating colorectal disease.

Epidemiology

Although rectal prolapse is thought by many to be a disease of the elderly, procidentia has a bimodal age distribution with peaks at the extremes of age. It can occur at any stage in life. In children it is most commonly diagnosed before 3 years, and is seen more often in boys. Rectal prolapse in adults generally occurs after the fifth decade and is associated with the female gender 80% to 90% of the time. The condition occurs infrequently, with an incidence in adults between 0.25 and 0.42% and a prevalence of 1% in adults more than 65 years of age. Despite this seemingly low number, it is a common condition evaluated by health care providers of all specialties, and especially those treating colorectal disease.

Causes

In children it is thought that rectal prolapse results from the lack of the natural sacral curve rather than a weakening of the pelvic floor. Without the sacral curve there is little or no anorectal angulation, which means the two structures lie in the same vertical plane. Increases in intra-abdominal pressure caused by diarrhea, vomiting, cough, or constipation therefore lead directly to increases in anorectal pressure and secondary rectal prolapse. Because this is a disorder of increased abdominal pressure rather than a weakened pelvic floor (as in adults), treatment involves relieving constipation and improving bowel habits rather than surgical repair. The remainder of this article focuses on adult procidentia.

Competing theories as to the cause of adult rectal prolapse have existed since the twentieth century. Moschcowitz proposed that the clinical picture was caused by an anterior sliding herniation of the pouch of Douglas secondary to a pelvic floor defect. However, the use of defecography by Broden and Snellman in 1968 showed that the disorder was a true full-thickness intussusception of the rectum through the anus, with a lead point approximately 6 to 8 cm from the anal verge. Nevertheless, it is widely thought that pouch of Douglas herniation is an early stage of the rectal prolapse process and, when combined with the loss of posterior rectal fixation, this inevitably leads to full-thickness rectal prolapse.

To develop procidentia patients must typically possess certain physiologic or anatomic abnormalities, which include the presence of an abnormally deep pouch of Douglas ; lax and atonic condition of the muscles of the pelvic floor and anal canal ; weakness of both internal and external anal sphincters, often with evidence of pudendal nerve neuropathy ; and the lack of normal fixation of the rectum, which results in a mobile mesorectum and lax lateral ligaments. There is debate as to what comes first. As the rectum chronically prolapses through the sphincteric complex, this inevitably leads to the muscles becoming more dilated/patulous, as well as to repeated trauma on the nerves. This ends in conditions ripe for a worsened pelvic floor state, which leads to more frequent prolapse, and the cycle continues.

Other risk factors associated with the development of adult procidentia are the same as those that predispose patients to a weak pelvic floor. These risk factors include age more than 40 years, female gender, multiparity, large birth weight of vaginally delivered babies, prior pelvic surgery, increased body mass index, chronic straining, chronic diarrhea, chronic constipation, cystic fibrosis, neurologic diseases that lead to denervation of the pelvic floor (ie, cauda equina syndrome, spinal cord lesions), connective tissue disorders (ie, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), dementia, and stroke. Even more than in routine patients, rectal prolapse in this cohort is often seen in conjunction with other pelvic floor defects. In rare cases, the immunologic myopathy of schistosomiasis has been linked to pelvic floor weakening and rectal prolapse.

Complications from untreated prolapse

Untreated rectal prolapse can result in several complications, including progressive problems with incontinence from chronic stretching and neuropathy, as well as constipation from obstructed defecation. Although some may consider these as more functional issues associated with the prolapse, rather than true complications, they can be progressive and debilitating. Long-standing prolapse can have second-order effects as well. The straining from constipation may lead to an anterior solitary rectal ulcer from repeated mucosal trauma. These ulcers are almost always associated with rectal prolapse or internal intussusception, and in severe cases may result in gastrointestinal hemorrhage and chronic pain. An infrequent acute complication is incarceration or strangulation of the prolapsed rectum, which is a surgical emergency ( Fig. 2 ). Complete prolapse is also associated with a ∼4-fold increase in relative risk of colorectal malignancy, although there is likely no causative effect, but it highlights the need for screening in appropriate patients. For these reasons, it is important to accurately diagnose and appropriately evaluate and manage these patients.

Clinical evaluation

First and foremost, the diagnosis of rectal prolapse is a clinical diagnosis based on history and physical examination. Patients generally present complaining of an anal mass with defecation that may or may not spontaneously reduce. In some cases, this can occur with simple abdominal pressure (ie, Valsalva) or even bending or squatting. Associated symptoms include fecal or mucous soilage, incomplete bowel evacuation, and abdominal/pelvic discomfort. Pain is usually not an associated symptom. Furthermore, up to 75% of patients with procidentia report incontinence, whereas 15% to 65% report constipation.

The hallmark physical examination finding of complete rectal prolapse is concentric rectal rings protruding through the anus (see Fig. 1 ). Unless severe disease exists, eliciting the prolapse may prove difficult in the clinical setting. It is important to examine the patient during Valsalva, because this often reproduces the prolapse and allows assessment of puborectalis function. It may be necessary to examine the patient in the squatting position or even on the commode to simulate defecation. An enema may be used to help induce the prolapse in the clinic for patients with a strong history but whose conditions are difficult to visualize on initial examination. Although many colorectal surgeons use prone-jackknife position for routine evaluations, this may fail to show even a moderately sized prolapse.

Digital rectal examination should be performed, paying specific attention to the identification of masses or concomitant pelvic floor disorders such as cystocele, enterocele, or rectocele. Poor sphincter tone is almost universal in patients with rectal prolapse, and should be gauged both at rest and with squeeze. The function of the pelvic floor muscles, and particularly the puborectalis, may be assessed by asking the patient to Valsalva during the digital inspection. A lack of posterior relaxation of the muscular sling during Valsalva may indicate a nonrelaxing or paradoxic puborectalis muscle.

Differential diagnosis

Several conditions can mimic rectal prolapse, both in terms of symptoms and clinical examination. For example, acute hemorrhoidal prolapse is common and is frequently confused with procidentia. This condition can be differentiated from rectal prolapse by the presence of radial rather than concentric folds as well as an everted and posterior anus rather than a normal, central anatomic anus. Rectal mucosal prolapse involves intussusception of only the mucosal layer through the anus, and therefore does not represent a complete, or full-thickness, rectal prolapse. It generally consists of a prolapse of less than 5 cm of tissue, whereas complete prolapse usually presents with more than 5 cm. Complete prolapse may be further differentiated from mucosal prolapse by palpating for a sulcus between the anal sphincter complex and the prolapsed tissue. A sulcus presents with complete prolapse, but is absent in mucosal prolapse. A sigmoidocele, or pouch of Douglas hernia, may represent the earliest stage of rectal prolapse, and generally presents as an anterior rectal bulge. Solitary rectal ulcers may present as a polypoid mass that is sometimes confused with rectal prolapse. Although these ulcers are almost always associated with rectal prolapse, they are a separate disorder caused by repeated mucosal trauma. In rare cases, a neoplasm (ie, malignant or pedunculated polyp) can present as rectal prolapse or be the lead point for prolapsing tissue.

Classification

No commonly accepted classification scheme exists to grade the extent of prolapse. Altemeier and colleagues initially categorized procidentia in terms of layer of prolapse (ie, mucosal vs full thickness) and their relationship to hemorrhoids and cul-de-sac sliding hernia. A more recent practical system was proposed by Beahrs and colleagues in 1972. This system is based on completeness of prolapse. Type I procidentia is defined as incomplete mucosal prolapse (partial prolapse). Type II procidentia is prolapse of full-thickness rectal layers (complete prolapse). Type II is further broken down into first-degree, second-degree, and third-degree prolapse, which correspond with high or concealed (internal intussusception or occult), externally visible with straining, and externally visible at all times, respectively.

Ancillary studies

Although rectal prolapse is diagnosed on physical examination alone, it is difficult to determine the extent of pelvic floor dysfunction in certain patients without further studies. The presence of other concomitant pelvic floor abnormalities such as cystocele, enterocele, rectocele, sigmoidocele, or vaginal vault prolapse may necessitate complex pelvic floor repair rather than simply addressing the rectal prolapse ( Fig. 3 ). As such, further diagnostic studies should strongly be considered in this cohort. In addition, those patients due for routine screening examinations or who have worrisome symptoms (ie, bleeding, changes in bowel habits, systemic symptoms) may require further evaluation.

Colonoscopy

Although the results of colonoscopy rarely influence the management of rectal procidentia, it is an important study to rule out other disorders, particularly neoplasm. Therefore, if a patient is of average risk and is current on recommended colorectal cancer screening, colonoscopy is not necessary for planning further management. For those patients with concerning symptoms or who are due for an examination, a colonoscopy to clear the colon is important before any prolapse repair. Colonoscopic findings often seen in rectal prolapse include anterior erythema and inflammation. Biopsy of these areas may show colitis cystic profunda, which is a benign finding that may be mistaken for adenocarcinoma. Solitary rectal ulcers may also be present, and are usually seen on the anterior wall at 4 to 12 cm from the anal verge. Ulceration and colitis cystic profunda may contribute significantly to the symptoms associated with procidentia. In addition, rectal inflammation with rectal granulomas can also be visualized and may signify occult procidentia (type II, first degree).

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is not required for diagnosing the prolapse; it is more useful in patients with significant fecal incontinence with questionable sphincter defects. In this setting, endoanal ultrasound is up to 90% sensitive and specific for detecting internal and external anal sphincter defects, which are present in approximately 70% of patients with complete prolapse. The addition of three-dimensional (3D) and four-dimensional technology allows real-time assessment of the pelvic floor during Valsalva, rest, and squeeze. Pelvic organ prolapse and avulsion of the puborectalis muscle during strain have both been reported using 3D ultrasound. However, the benefit of ultrasound examination for identifying and classifying pelvic organ prolapse remains in question. Deitz and colleagues showed that translabial ultrasound of patients with organ prolapse correlated well with clinical staging in all 3 compartments; however, a more recent study showed poor agreement between translabial ultrasound and evacuation studies in patients with obstructed defecation with rectocele or rectal prolapse. The use of ultrasound as part of the work-up for clinically diagnosed rectal prolapse is likely of minimal benefit, because sphincter defects are rarely addressed at the time of surgery for the prolapse. Furthermore, the narrow field of view and poor correlation with evacuation studies indicate that ultrasound is an inferior study for assessing global pelvic floor function. It is often best to repair the prolapse and pursue the sphincter evaluation only as needed after determining the functional response following repair.

Fluoroscopy

Cinedefecography allows the assessment of obstructed defecation (pelvic floor descent, anorectal angle, and percent of contrast evacuation) as well as rectal prolapse and internal intussusception. Physiologic and anatomic defects can be identified using fluoroscopy in up to 80% of patients with obstructed defecation. However, perhaps the most important aspect is the ability of fluoroscopy to identify concomitant pelvic floor disorders such as cystocele, rectocele, sigmoidocele, or enterocele, which are present in 15% to 30% of patients with rectal prolapse. These disorders may contribute to an increased recurrence rate after surgery if not addressed. Therefore, they should be identified before surgery and either repaired or discussed with the patient regarding the possibility of a need for subsequent repair. Preoperative defecography has been shown to affect management strategy in up to 40% of patients. Cinedefecography is therefore recommended for patients in whom concomitant complex pelvic floor anomalies are suspected.

Dynamic Pelvic Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The benefit of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) compared with fluoroscopy or ultrasound is that it is noninvasive, provides simultaneous dynamic evaluation of all pelvic organs in multiple plains, and allows visualization of pelvic floor support structures. It has been shown to correlate well with fluoroscopic studies in the identification of pelvic organ prolapse, and frequently alters the surgical approach. This finding is highlighted in one study showing that dynamic MRI changed the operative approach in 67% of patients with fecal incontinence. It has not been specifically studied in the rectal prolapse population; however, patients with the potential for concomitant pelvic floor disorder may benefit from a dynamic study to determine whether a complex pelvic floor reconstruction is necessary. Dynamic MRI accomplishes this with 1 noninvasive test, rather than multiple fluoroscopic studies that separately assess for cystocele, sigmoidocele, rectocele, or enterocele.

Colonic Transit Marker Studies

Transit studies are an important element in the work-up for chronic constipation, but they have limited usefulness in the specific evaluation of rectal prolapse. Although 1 small study showed a slightly prolonged colonic transit time in full-thickness prolapse compared with internal intussusception, there was no significant difference from idiopathic constipation. In another study addressing transit times before and after Ripstein rectopexy, the investigators showed that prolonged preoperative transit times correlated with evacuation difficulties after surgery. Other investigators have shown decreased colonic transit times in patients with prolapse after resection rectopexy versus controls or rectopexy alone. Thus, it may be that the main potential benefit of transit studies is the preoperative identification of patients who are best suited for a resection, especially for those patients who may be under consideration for a total abdominal colectomy versus a sigmoid resection (standard resection rectopexy) because of underlying colonic inertia.

Anorectal Manometry

The use of anorectal manometry in patients with procidentia commonly shows a decreased anal resting pressure, normal or decreased squeeze pressure, and a dampened anorectal inhibitory reflex. There are differing data regarding the ability of preoperative manometry to predict postoperative continence. One prospective study of 23 patients showed higher rates of postoperative continence in patients with higher preoperative resting and maximum squeeze anal pressures. However, a larger retrospective study identified only preoperative maximum squeeze pressure greater than 60 mm Hg as predicting lower rates of postoperative incontinence. The same study found no association between degree of incontinence and manometry findings. Regardless of the ability of manometry to accurately predict postoperative incontinence, its use rarely (if ever) changes the operative strategy, because nearly all patients have improvements in anorectal pressures after surgery. Therefore, it is likely better to await the changes in function after surgery before using these tests outside limited indications.

Pudendal Nerve Terminal Motor Latency

Pudendal nerve terminal motor latency (PNTML) can be used to test the nerve function of the external sphincter, which is generally prolonged in those with procidentia. Although postoperative unilateral or bilateral pudendal neuropathy has been associated with higher rates of postoperative incontinence, no studies have shown the ability of preoperative PNTML to predict postoperative functional outcome. In addition, the neuropathy that is characteristic of the repetitive trauma use with chronic prolapse is likely to lead to prolonged PNTML in a large percentage of cases.

Electromyography

Electromyogram (EMG) has also been used to assess the functionality of the sphincter complex. One study looking at EMG results in patients with fecal incontinence and/or rectal prolapse found that abnormal results are almost always seen in patients with fecal incontinence, either with or without concomitant rectal prolapse. However, in patients with rectal prolapse and no incontinence, the results of EMG are usually normal. Based on these results, there may be a difference in the pathophysiology of rectal prolapse in patients with and without fecal incontinence. Either way, there seems to be little or no role for preoperative EMG in patients with straightforward rectal prolapse, because the results have no impact on management.

Management

Nonoperative Therapy

Although surgical management is the gold standard for treating complete prolapse, several nonoperative therapies have also been described. For patients with incomplete prolapse, minimally symptomatic prolapse, or who are poor surgical candidates, conservative measures may provide some benefit. Because rectal prolapse is associated with alterations in bowel habits, initial nonoperative interventions should be directed at minimizing these alterations to the greatest extent possible. All patients should therefore take in 25 to 30 g of fiber per day in addition to drinking 1 to 2 L of water. Biofeedback and pelvic floor exercises (ie, Kegel) have shown benefit in patients with incontinence and obstructed defecation, and should strongly be considered in such patients who present with rectal prolapse. As a last-line therapy, a perineal pad may be placed to act as a sort of truss. Conservative measures do not fully reverse or correct a prolapsed pelvic organ, and these serve as temporizing or palliative procedures in most cases.

Operative Repair

Primary indications for operative repair of procidentia include the sensation of an anal mass, fecal incontinence, or chronic constipation. However, the presence of rectal prolapse can be considered an indication for surgery, because the disorder is progressive and may lead to rectal incarceration/strangulation. Although the goals of surgical therapy are to improve or restore fecal continence, and to correct functional constipation from outlet dysfunction or obstructed defecation, these results are widely variable. The major objective is to resolve/reduce the prolapse. Several operations have been described for the treatment of rectal prolapse, and, as with most disorders that have multiple described surgical approaches, no single, ideal operation exists. Nevertheless, all operative techniques use one or both of the basic principles of rectal prolapse repair: rectal fixation to the sacrum and resection or plication of redundant bowel. The finer details regarding the degree of rectal dissection in each plane, whether or not to divide the lateral ligaments, the use of mesh, and the surgical approach (transabdominal vs perineal, laparoscopic vs open vs robotic) are all heavily debated points of contention.

Abdominal versus perineal

The 2 broad categories of operative approach are abdominal and perineal. The benefit of the perineal approach is that it can be performed under regional, or even local, anesthesia. As such, it is ideally suited for older, sicker patients who cannot tolerate general anesthesia. Based on several observational and retrospective studies, it is commonly thought that surgery via a perineal approach is associated with higher rates of recurrence. Madiba and associates performed the most extensive review of the literature and determined that abdominal approaches have decreased recurrence rates (0%–12%) compared with perineal approaches (0%–38%), although improvement in functional outcomes seemed similar. Overall mortality remained low (0%–6%) for all procedures. Only 1 randomized, prospective study has directly compared perineal proctosigmoidectomy and pelvic floor repair (levatorplasty) with abdominal rectopexy and pelvic floor repair. Recurrence rates were similar in both arms, although functional outcomes were significantly improved in the abdominal rectopexy group. Fecal incontinence, maximum anal resting pressure, rectal compliance, and frequency of bowel movements were all improved in patients who underwent abdominal rectopexy relative to patients who underwent a perineal surgery. Although these differences were statistically significant, it is difficult to draw strong conclusions because the study only included 10 patients per group. The largest prospective, randomized trial to date, the PROSPER trial (prolapse surgery; perineal or rectopexy), has finished recruiting patients but has yet to publish any long-term results. This study will enhance understanding of differential outcomes between perineal and abdominal approaches.

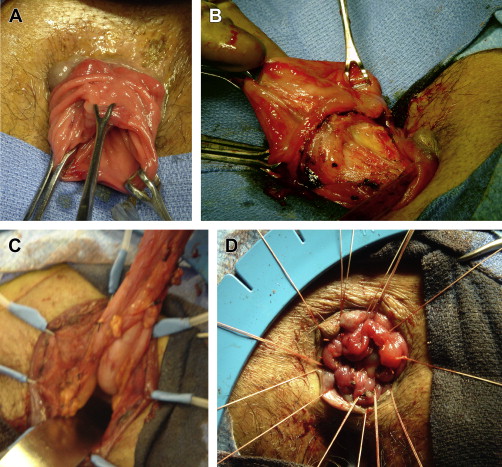

Perineal approaches

Perineal approaches include perineal proctosigmoidectomy (Altemeier procedure), mucosal sleeve resection (Delorme procedure), and anal encirclement (Thiersch procedure) ( Tables 1 and 2 ). Perineal rectosigmoidectomy involves the full-thickness excision of the rectum and a portion of the sigmoid colon followed by a low anastomosis just proximal to the levators ( Fig. 4 ). The procedure is associated with high rates of postoperative morbidity (up to ∼35%, in part caused by patient selection) and recurrence (up to 26% with prolonged follow-up). Of particular concern are the poor functional outcomes that include high rates of incontinence, soilage, and urgency, largely caused by the loss of the compliant rectum along with a reduction in resting anal sphincter pressure. For this reason, many surgeons recommend a levatorplasty in conjunction with the rectosigmoidectomy, which recreates the anorectal angle. The addition of levatorplasty to rectosigmoidectomy improves both the recurrence rate and functional outcomes, to include continence and frequency of defecation. There are some data to suggest that rectosigmoidectomy with concomitant levatorplasty is associated with the longest recurrence-free interval, the lowest overall recurrence rate, and the best functional outcomes of all the perineal procedures. The downside to levator repair mainly relates to an increased rate of dyspareunia in women.

| Delorme Procedure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | Follow-up (mo) | Recurrence, No. (%) | Constipation (%) | Continence (%) |

| Monson et al, 1986 | 27 | 35 | 2 (7) | NS | NS |

| Graf et al, 1992 | 14 | 18 | 3 (21) | NS | 55 (+) |

| Senapati et al, 1994 | 32 | 21 | 4 (12.5) | 50 (+) | 46 (+) |

| Oliver et al, 1994 | 41 | 47 | 8 (22) | NS | 58 (+) |

| Tobin and Scott, 1994 | 43 | 20 | 11 | NA | 50 (+) |

| Lechaux et al, 1995 | 85 | 33 | 11 (14) | 100 (+) | 45 (+) |

| Kling et al, 1996 | 6 | 11 | 1 (17) | 100 (+) | 67 (+) |

| Agachan et al, 1997 | 8 | 24 | 3 (38) | NS | (+) |

| Pescatori et al, 1998 | 33 | 39 | 6 (18) | 44 (+) | (+) |

| Yakut et al, 1998 | 27 | 38 | 4 (4.2) | NS | NS |

| Watts and Thompson, 2000 | 101 | 36 | 30 (27) | 13 (+) | 25 (+) |

| Liberman et al, 2000 | 34 | 43 | 0 | 88 (+) | 32 (+) |

| Lieberth et al, 2009 | 76 | 43 | 14.5 | 7 (+) | 79 (+) |

| Youseff et al, 2013 | 82 | 12 | 8.5 (7) | 18 (−) | 85 (+) |

| Perineal Rectosigmoidectomy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | Follow-up (mo) | Recurrence, No. (%) | Constipation (%) | Continence (%) |

| Theuerkauf et al, 1970 | 13 | NS | 38.5 | NS | 33.3 (+) |

| Altemeier et al, 1971 | 106 | 228 | 3 (3) | NS | NS |

| Friedman et al, 1983 | 20 | 12–204 | 7 (35) | NS | 30 (+); 20 (−) |

| Gopal et al, 1984 | 18 | NS | 1 (5.6) | NS | NS |

| Watts et al, 1985 | 33 | 23 | 0 | NS | 6 (+); 22 (−) |

| Prasad et al, 1986 | 25 | NS | 0 | NS | 88 (+) |

| Williams et al, 1992 | 56 | 12 | 6 (6) | NS | 46 (+); 0 (−) |

| Williams et al, 1992 | 11 | 12 | 0 | NS | 91 (+) |

| Takesue et al, 1999 | 10 | 42 | 0 | NS | (+) |

| Johansen et al, 1993 | 20 | 26 | 0 | NS | 21 (+) |

| Ramanujam et al, 1994 | 72 | 120 | 4 (6) | NS | 67 (+) |

| Deen et al, 1994 | 10 | 18 | 1 (10) | NS | 80 |

| Agachan et al, 1997 | 32 | 30 | 4 (13) | NC | (+) |

| Agachan et al, 1997 | 21 | 30 | 1 (5) | NC | (+) |

| Kim et al, 1999 | 183 | 47 | 29 (16) | 61 (+) | 53 (+) |

| Glasgow et al, 2008 | 45 | 44 | 4 (8.9) | 12 (+) | 19 (+) |

| Lee et al, 2011 | 123 | 13 | 14 (11.4) | NS | NS |

The Delorme procedure involves stripping the mucosa of the prolapsing rectum from the sphincters and muscularis propria, followed by plication of the muscularis propria and reanastomosis of the mucosal ring. Recurrence rates are high, ranging from 4% to 38%; however, the addition of posterior levatorplasty and sphincter repair has been shown to significantly decrease recurrence rates and improve functional outcomes in patients with concomitant severe pelvic floor disorders. Pescatori and colleagues added sphincteroplasty to the Delorme procedure in their series, and likewise noted improvements in continence and constipation compared with the Delorme procedure alone. The Delorme procedure is especially prone to failure in cases of proximal procidentia with rectosacral separation on defecography, fecal incontinence, chronic diarrhea, or perineal descent greater than or equal to 9 cm on straining, and should therefore generally be avoided in these patients.

The Thiersch procedure involves encircling the external anal sphincter with either a silver wire or some other prosthetic material. This procedure does not directly address the prolapsing tissue, but prevents further descent by tightening the anal sphincter. With recurrence rates of 33% to 44% and improvements in modern anesthesia, there is limited or no role for its use. More recent technical variants of the traditional Thiersch procedure that have shown promise include the use of a magnetic ring for patients with fecal incontinence, but these have not been described specifically for rectal prolapse.

Abdominal procedures

Suture rectopexy

Abdominal procedures include suture rectopexy, posterior prosthetic or mesh rectopexy, anterior sling rectopexy (Ripstein procedure), and ventral rectopexy ( Table 3 ). For suture rectopexy, the rectum is thoroughly mobilized and sutured or tacked to the sacral fascia. Although the sutures/tacks hold this in place, it is the adhesions and fibrosis resulting from the dissection that secure the rectum to the presacral fascia, which prevents recurrence by protecting from the descent of redundant tissue. Recurrence rates range from 0% to 27%, although most studies report rates from 0% to 3%. The procedure is associated with considerable variation in postoperative constipation. In part this is secondary to the degree of rectal mobilization. Although most repairs carry the posterior dissection down to the pelvic floor, the anterior and lateral dissections are variable. Division of the lateral attachments has been shown to be associated with lower rates of recurrence at the cost of increased constipation. However, fecal incontinence is most often improved by suture rectopexy, likely from simple avoidance of the mass protruding through the sphincters.