Chronic pelvic pain is pain lasting longer than 6 months and is estimated to occur in 15% of women. Causes of pelvic pain include disorders of gynecologic, urologic, gastroenterologic, and musculoskeletal systems. The multidisciplinary nature of chronic pelvic pain may complicate diagnosis and treatment. Treatments vary by cause but may include medicinal, neuroablative, and surgical treatments.

Key points

- •

Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is a difficult problem to treat that affects approximately 15% of women and unknown percentage of men.

- •

CPP may be difficult to diagnose and treat because causes, evaluation, and treatments may traverse multiple specialties.

- •

The most common causes for CPP include endometriosis, adhesions, musculoskeletal pain, and neurologic dysfunction.

- •

Patients with CPP are more likely to have other somatic pain syndromes, constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, or a history of sexual or physical abuse.

- •

Treatments of CPP are cause-specific. For patients who lack a clear cause, NSAIDs, tricyclic antidepressants, biofeedback, and neuroablative techniques are used.

Introduction

The evaluation and successful treatment of pelvic pain is a complex problem. Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) may encompass gastroenterologic, urologic, gynecologic, oncologic, musculoskeletal, and psychosocial systems. Subspecialists often lack interdisciplinary training and understanding of the diverse causes needed to evaluate and treat patients. This deficit makes comprehensive evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment difficult, and may frustrate patients who are sent from one specialist to another for further evaluation and diagnosis.

This article attempts to create a multidisciplinary overview for evaluation, testing and treatment options. It reviews the most common causes of CPP and discusses management options. Finally, some obstacles to treatment are reviewed and ways to improve efficiency of evaluation and treatment are suggested.

Introduction

The evaluation and successful treatment of pelvic pain is a complex problem. Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) may encompass gastroenterologic, urologic, gynecologic, oncologic, musculoskeletal, and psychosocial systems. Subspecialists often lack interdisciplinary training and understanding of the diverse causes needed to evaluate and treat patients. This deficit makes comprehensive evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment difficult, and may frustrate patients who are sent from one specialist to another for further evaluation and diagnosis.

This article attempts to create a multidisciplinary overview for evaluation, testing and treatment options. It reviews the most common causes of CPP and discusses management options. Finally, some obstacles to treatment are reviewed and ways to improve efficiency of evaluation and treatment are suggested.

Definition of CPP

Pelvic pain is divided into acute and chronic pain. Acute pain is typically caused by a precise cause, such as anal fissure or thrombosed external hemorrhoid. Acute pain tends to diminish and it resolves with treatment and healing; it is not discussed in this article. In contrast, CPP is described as pain lasting a minimum of 6 months in duration, which may be sudden or gradual in onset and affects “the visceral or somatic system and structures supplied by the nervous system from the 10th thoracic spinal level and below.” Because of the broad definition of pelvic pain, the evaluation of pelvic pain extends across many subspecialties and organ systems.

Epidemiology of CPP

CPP is a ubiquitous disease; in the United States it is estimated that 9 million women between ages 18 and 50 or 15% of the female population suffer from CPP. A study from the United Kingdom demonstrated a CPP rate of 24%, with 33% of women reporting 5 years or greater duration. A study in New Zealand found a prevalence of 25.4%. A 1994 Gallup poll estimated the direct cost of CPP at $881.5 million dollars annually, with 15% of women with CPP noting lost work revenue and 45% reporting decreased work productivity.

Ideally, a specific cause can be elucidated; however, in many cases, a distinct diagnosis is never discovered. Population studies demonstrate between 50% and 61% of all women with pelvic pain lack a clear diagnosis. Even patients who undergo diagnostic laparoscopy still lack a diagnosis in 30% to 40% of cases.

An epidemiologic study found that women with CPP are more likely to have a history of spontaneous abortion, military service, nongynecologic surgery, and nonpelvic somatic complaints than controls. Additional studies have demonstrated a correlation with history of multiple sexual partners and psychosexual trauma or abuse. CPP subjects are four times as likely to have a history of pelvic inflammatory disease. Subjects with CPP also have a higher incidence of constipation, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), depression, and anxiety than control groups.

Although CPP is better described and is more prevalent in women, it is not exclusive to the female gender. Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain (CP/CPP) is a well-described cause of pelvic pain in men. Musculoskeletal disorders may also be present with pelvic pain. As the diagnosis of CPP is better understood and known, it is likely that more men will present with similar complaints.

Relevant history for patients with CPP

History is a vital element in evaluation of CPP. Given the complexity of elements involved, a thorough history must include history of gastroenterologic, gynecologic, urologic, musculoskeletal, and pain symptoms. A full review of systems, including infectious diseases, endocrine disorders, and psychiatric disorders, is necessary. The International Pelvic Pain Society provides an extensive history intake form.

A discussion of the character, intensity, radiation, and chronicity of pain should be obtained. Duration of pain, and exacerbating and alleviating factors, should be determined. Daily variation may give clues to the cause. Pelvic congestion syndrome typically increases in intensity as the day progresses, whereas proctalgia fugax tends to awaken the patient at night.

Determining the relationship of pain to each organ system is important. From a gynecologic perspective, correlation with sexual activity is also important. Pain associated with superficial stimulation is more consistent with vaginitis or vulvodynia; whereas deep dyspareunia is consistent with endometriosis or pelvic inflammatory disease. Abnormal vaginal bleeding may be symptomatic of uterine leiomyomas, adenomyosis, or malignancy, and should be evaluated with pelvic ultrasound. A history of high-risk sexual behavior, multiple partners, and/or genital discharge can suggest pelvic inflammatory disease.

A history of pain or pressure with urination, difficulty emptying, or frequency suggests urologic causes. History of gastrointestinal disorders, including constipation and IBS, can be helpful. Manual evacuation and vaginal digitation are consistent with obstructed defecation. A history of recent trauma or pregnancy may help illuminate a musculoskeletal cause and surgical interventions 3 to 6 months ago may suggest adhesive disease. Copies of colonoscopies, operative reports, or pathologic specimens are crucial. Previous perineal operations, mesh placement, and radiation may suggest iatrogenic causes.

Visceral and somatic pain may be sensed differently. Because visceral innervation of the pelvic structures share common neural pathways, distinguishing the cause of visceral pain may be difficult. Visceral pain is associated with dull, crampy, or poorly localized pain, and may be associated with autonomic phenomena such as nausea, vomiting, and sweating. Somatic pain, in contrast, originates from muscles, bones, and joints, and typically presents according to specific dermatomes. Somatic pain is associated with sharp or dull pain. Neuropathic pain may produce burning, paresthesia, or lancing pain. A history of pain syndromes, or drug or alcohol, abuse may also factor into evaluation and treatment. Janicki has described a centralized sensitization of the pain receptors in patients with CPP and has suggested that understanding this may also be necessary for success.

An evaluation should also determine level of functional disability. The patient’s ability to work, engage in daily activities, and emotional and sexual relationships is relevant. A full psychological evaluation should be considered for patients with history of sexual, physical abuse, depression, or anxiety. This does not alleviate the need for physical diagnosis; however, recognition and treatment may be important elements in symptom improvement.

Physical examination

The physical examination encompasses multiple specialty examinations and may be time consuming for the practitioner and difficult for the patient with CPP. The entire examination and evaluation may require several visits to complete. All practitioners should have a chaperone during invasive examinations and at least one member of the medical team should be female.

Before commencing a formal examination, the practitioners should evaluate patient gait, movement, and sitting pose. Patients with pelvic girdle pain or spinal pain may have difficulty ambulating and sit off to one side; the practitioner should question the patient on this.

Specific areas of concern include the abdomen and abdominal wall. Patients should be examined for scars and previous surgeries or complications from surgeries should be reviewed. The abdomen should be palpated for tenderness, masses, or lesions. Distension and bloating may suggest history of constipation or bowel obstruction. The area of greatest abdominal pain should be localized. Performing a Valsalva maneuver or asking the patient to raise her head and legs separates the visceral organs from abdominal wall and may identify pressure points. Flexion of the head reduces abdominal pain and points to a visceral origin; conversely, increasing pain suggests abdominal wall or musculoskeletal origin.

The pelvic examination should commence with visual inspection noting areas of discoloration, dermatologic disorders, or sequelae of infection. A Q-tip examination using light touch is used to evaluate the sensory and neurologic systems of the perineum. Signs of incontinence at baseline or with straining should be noted. Pelvic organ prolapse quantification (Pop-Q) examination should be performed. Rectal prolapse can be noted during propulsive activity as well. Preferably, patients should be examined in both a reclining and standing position for greater sensitivity.

Anteriorly, the urethra and bladder trigone should be evaluated. A mass by the urethra suggests ureteral diverticulum, whereas tenderness and dysuria suggests urethritis, urethral syndrome, or interstitial cystitis (IC). A urinalysis can evaluate for infectious causes of urologic origin. Hematuria is associated with endometriosis. If urinary tract cause is suggested, a cystoscopy with evaluation for Hunner ulcers and a potassium chloride (KCl) sensitivity test to evaluate for IC are warranted. Urodynamics are indicated if urinary dysfunction exists.

In the vaginal compartment, an evaluation for vaginal discharge, Pap smear, and bimanual examination should be performed. Vaginal discharge and cervical motion tenderness are concerning for sexually transmitted diseases and can be further evaluated with cultures or histology. Tenderness may suggest vulvodynia or vaginitis.

A rectal examination should include digital examination and anoscopy to evaluate for lesions. For patients with bleeding, inflammation, or lesions noted on anoscopy, a colonoscopy may be warranted. Fissures, hemorrhoids, fistulas, or abscesses can cause chronic anal pain. Pain on rectal examination without fluctuance can be a sign of an intersphincteric abscess, which may have no external signs.

The musculoskeletal examination should evaluate the abdominal wall and pelvic floor muscles. During vaginal examination, the levator plate should be palpated on both sides of the vagina. A finger is curved over the levators during relaxation and contraction to evaluate for tenderness. The piriformis muscle is palpated through the vagina, cephalad to the ischial spine in a posterior lateral direction. The piriformis is lateral to the bulbospongiosus and transverse perineum that run parallel to the vagina. The internal and external sphincter muscles are evaluated transanally at rest and with contraction. Note should be made of weakness or deficiency. During normal contraction, a slight upward pull should be felt from the coccygeus, puborectalis, and pubovaginalis muscles. During propulsion, descent of the pelvic wall and motility of the rectum should be noted.

The coccyx should be evaluated for coccygodynia. Pain with palpation or mobility is a sign of coccygodynia; a normal coccyx should rotate 25° to 30° without discomfort. External rotation of the leg against resistance may exacerbate the pain. Flexion of the hip and knee against resistance may demonstrate psoas pain. Additional musculoskeletal evaluation includes evaluation of pelvic ring instability, which is particularly common after delivery. Straight leg raise, resisted hip abduction, adduction tests, and posterior provocative pain test may be helpful in evaluating the stability of the pelvic ring.

If the examination fails to elicit a clear cause for their pain, an MRI may be helpful. In a study of subjects with CPP and no specific clinical findings, MRI was able to elucidate a cause in 39% of cases. For the remainder, 36% of subjects were ultimately diagnosed with levator ani syndrome and 25% with unspecified anorectal pain. Other testing includes pelvic ultrasound, cystoscopy, and colonoscopy. In the past, laparoscopy was performed for diagnostic purposes but is no longer indicated.

Common causes for CPP

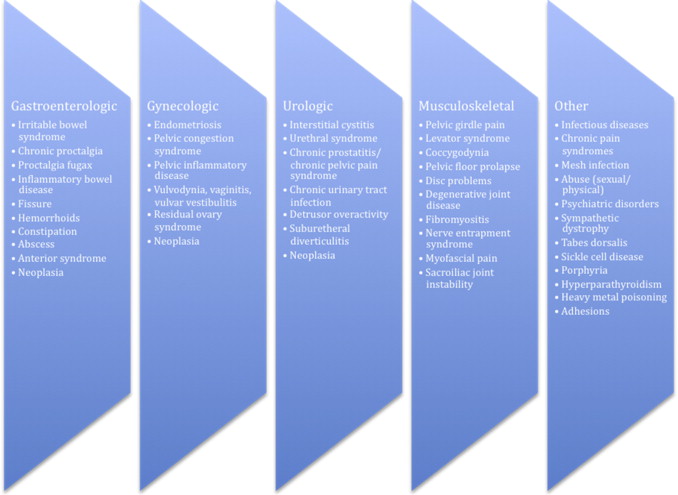

The three most common documented findings on laparoscopy for CPP are endometriosis (33%), adhesions (24%), and absence of pathologic condition on laparoscopy (35%). However, hundreds of different causes may cause pelvic pain ( Fig. 1 ). Because normal pelvic function requires coordinated activity of the muscular, connective, visceral, and neural tissues of the pelvis, dysfunction in any area can create a complex situation that may ultimately manifest itself as pelvic pain.

Gynecologic

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is one of the leading causes of CPP in women. Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial tissue outside of the uterine cavity. Areas of involvement may include proximal or distant sites and may affect gastroenterologic and gynecologic function secondary to local or metastatic invasion.

Typically, patients are nulliparous, in their 20s and 30s, with symptoms correlated with menstrual cycle, including dysmenorrhea and pain. Deep dyspareunia and involuntary infertility are also common. Patients are often diagnosed by symptoms alone, but diagnostic laparoscopy with findings of chocolate cysts and powder puff staining help to confirm the diagnosis. Up to 40% of patients may have no finding at laparoscopy. Severity of pain is not generally correlated with gross or pathologic findings during surgical extirpation. Noninvasive diagnosis is being evaluated using ultrasound and pelvic MRI.

Treatment of endometriosis is often hormonal, including oral contraceptives or induced menopause, which may lead to the atrophy of implants and relief of symptoms. Acupuncture has been used with success in some cases. Presacral neurectomy or laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation (LUNA) may decrease symptoms; however, these are not endorsed by a recent Cochrane review. Surgical excision, abdominal hysterectomy, and salpingo-oophorectomy may be recommended in refractory cases.

Pelvic congestion

Pelvic congestion is most frequently seen in women between 20 and 30 years old, and is analogous to a scrotal varicocele in men. Symptoms generally worsen before menstruation and increase in severity during the day. Patients may also complain of deep dyspareunia or postcoital pain. Dilated vessels can be seen on imaging such as duplex venography, MRI, or during laparoscopy. Pathologic findings including fibrosis of tunica intima and media are noted with hypertrophy and proliferation of capillary endothelium. Both ovarian suppression and embolic treatment seem to control symptoms, with embolic treatment success varying from 24% to 100% in studies.

Vulvodynia, vaginitis, and vulvar vestibulitis syndromes

Vulvodynia, vaginitis, and vulvar vestibulitis syndromes, as well as clitoral pain, are forms of pain localized to the anterior compartment. It is hypothesized they are caused by stretching of the perivaginal and perivulvar muscles, hormonal changes, or contact irritation. Symptoms are typically intermittent in nature and may be experienced as itching, burning, stinging, rawness, or dyspareunia. Onset may occur after first sexual experience or tampon use, but may also occur after trauma such as delivery or vigorous sexual activity. Laboratory testing is generally performed to rule out infectious and dermatologic causes. A cotton swab or Q-tip test can localize areas of sensitivity. Management generally consists of biofeedback to desensitize the affected region, including application of manual therapy or electrotherapy. Topical agents such as lidocaine or lubricant may be helpful and, in some patients, botulinum toxin type A (Botox) injections are efficacious. Up to 50% of patients may respond to pain medications, such as tricyclic agents, or gabapentin. Behavioral therapy and interventional pain techniques may be helpful in patients who fail to respond to initial treatments.

Urologic

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain (CP/CPP)

Although CPP is generally recognized as an entity affecting women, men can also have CPP. In addition to a multitude of musculoskeletal ailments, men can develop CP/CPP. This syndrome was recognized by the National Institute of Health in 1995. It is characterized by CPP and voiding symptoms in the absence of urinary tract infection, anatomic abnormality, or urologic malignancy. Inflammatory and noninflammatory types, depending on the presence or absence of leukocytes in expressed prostatic secretions, have been described. A 2013 review of articles on CP/CPP suggested treatment options and advocated a multimodal therapeutic approach that may include use of alpha-blockers in patients with significant voiding symptoms, and physical therapy or antibiotics for newly diagnosed antimicrobial-naive patients.

Interstitial cystitis (IC)

Symptoms of IC include bladder pain, urinary frequency, urgency, or nocturia. Pain is often present in the suprapubic area but it may occur in the lower back or buttock. Fifty-one percent of women complain of dyspareunia. Concomitant fibromyalgia, vulvodynia, anxiety, and depression are common.

Urinalysis is generally performed to rule out urinary tract infection. On cystoscopy, Hunner ulcers may be seen in the bladder mucosa and a KCl sensitivity test is used to obtain a definitive diagnosis. The KCl sensitivity test evaluates the bladder for increased epithelial permeability that is believed to contribute to IC. This test is positive in up to 75% of patients, although false positives may occur.

First-line treatment of IC is generally nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication (NSAID), although neither NSAIDs nor opioids have been noted to be effective. Pentosan polysulfate sodium (PPS) is the only treatment of IC approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). PPS is hypothesized to mimic the normal glycosaminoglycan layer that protects the bladder urothelium that is dysfunctional in IC. Treatment is effective in 28% to 32% of patients but may require up to 6 months of treatments. Use of PPS in conjunction with tricyclic antidepressants may have better results. Both dimethyl sulfoxide and heparin have been administered as intravesicular injection with limited success, and Botox in combination with hydrodistention has been used with some efficacy. Sacral nerve stimulation has been used for patients who failed other therapies.

Urethral syndrome

Urethral syndrome is associated with incomplete emptying and burning during urination, particularly after intercourse. The urethra may be tender on examination. It is believed that urethral syndrome is caused by noninfectious, stenotic, or fibrous changes in the urethra. Urethral syndrome is associated with grand multiparity, delivery without episiotomy, and general pelvic relaxation. Treatment generally consists of diathermy and coagulation.

Gastroenterologic

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

IBS is defined as the chronic presence of abdominal pain or discomfort 3 days or more per month that correlates with stooling, change in frequency, or form of stool. IBS is believed to be multifactorial in origin and related to the hypersensitivity of the viscera leading to disproportionate pain with intestinal distension, dysregulation of gastrointestinal motility, and endocrine effects of hypothalamic pituitary axis.

IBS is a diagnosis of exclusion. Other causes that may cause bowel dysfunction, such as Crohn’s disease, diverticulitis, sprue, lactose allergy, and chronic appendicitis, must be ruled out. There is a strong association between CPP and IBS; 65% to 79% of patients with IBS have CPP and 60% of patients have associated dysmenorrhea.

Dietary modification may be helpful to decrease symptomatology. For patients with diarrhea, loperamide, cholestyramine, and alosetron (for women) are most commonly recommended. A trial of rifaximin has been shown to provide symptom relief but is not yet approved by the FDA for IBS. Constipation is generally treated with dietary and supplementary fiber, stool softener, or cathartics such as lactulose and polyethylene glycol. A 2007 Cochrane database reviewed the use of tegaserod, a 5-hydroxytryptamine partial agonist and found patients were more likely to have modest relief than with placebo. Tricyclic antidepressants, smooth muscle relaxants, and serotonin reuptake inhibitors have also been used with some success.

Chronic proctalgia

Chronic proctalgia is defined as chronic or recurrent anorectal pain lasting for 20 minutes or longer, in the absence of other anorectal causes of pain such as hemorrhoids, fissures, and coccygodynia. Patients often describe a burning sensation, which may worsen with defecation or sitting and improve when supine. Symptoms are generally more common in women and are often associated with other bowel dysfunction, such as obstructed defecation. Proctalgia has an incidence of 2% to 5%. First-line therapy for patients with chronic proctalgia and obstructed defecation is generally biofeedback with success rates as high as 65%. For patients without defecatory symptoms, Botox may be used as well. Tricyclic antidepressants, sacral nerve stimulation, and pain medication are reserved for refractory cases.

Proctalgia fugax

Proctalgia fugax is sudden nocturnal cramping that occurs and spontaneously resolves without objective findings and has an incidence of 8% to 18%. Episodes are localized to the anus or lower rectum and last for seconds to minutes. Complete cessation of pain occurs between episodes. There is some association with high resting and squeeze pressures that may improve with biofeedback. If pain is unilateral, entrapment of the pudendal nerve at the Alcock’s canal should be considered. First-line treatment includes topical diltiazem or nitroglycerin, injection of Botox, or strip myomectomy in severe cases in which internal anal sphincter is thickened. Injection of the pudendal nerve and sphincterotomy have both been used with some success. Sacral nerve modulation has also been effective.

Musculoskeletal

Pelvic girdle pain

Pelvic girdle pain presents as posterior sacral or buttock pain of variable intensity. It is generally associated with recent pregnancy or pain that started during pregnancy. One to sixteen percent of women have pain lasting longer than 12 months postpartum. Evaluation consists of musculoskeletal testing, including straight leg raise, provocative testing, palpation of sacroiliac ligament, resisted hip abduction, and adduction tests. Treatment is generally multidisciplinary and includes an exercise program focusing on restoring pelvic stability. Occasionally intra-articular injections with steroids are given for sacroiliac joint pain. Pain medications are generally avoided, except for antiinflammatory medications. For severe cases, radiofrequency thermocoagulation, cryoneurolysis under fluoroscopic guidance, and pulsed radiofrequency have been used with lasting improvement.

Levator syndrome

Levator syndrome is generally attributed to muscle spasm of the pelvic floor musculature and consists of wide range of complex musculoskeletal disorders, including piriformis and puborectalis syndromes. Symptoms are generally a vague dull pressure or ache that may worsen with sitting or lying down. It is often associated with incomplete evacuation. It is more common in women, with an incidence of approximately 6%. Diagnosis is made with palpation of muscles and associated tenderness. Digital massage is associated with improvement in symptoms in up to 68% of patients. Lidocaine, methylprednisolone, and triamcinolone have also been injected with varied results. Case reports also demonstrate improvement after injection of Botox. Biofeedback has been used with approximately 30% of patients noting improvement.

Coccygodynia

Coccygodynia is pain at or around the coccyx evoked by manipulation of the coccyx. It is typically associated with local trauma, prolonged sitting, or cycling. It may be exacerbated by sitting, bending, or arising, as well as during intercourse or defecation. Coccygodynia may be secondary to hypertonicity of the pelvic floor and decreased coccyx mobility. The cause may be unknown in up to 30% of cases. Diagnosis can be confirmed by relief of pain after injection of local anesthetic. Treatment options include antiinflammatory medications, rest, coccyx cushion, physical therapy, and massage. If the coccyx is unstable or hypermobile, local injection may be more useful compared with manual stretching. Radiofrequency thermocoagulation, pulsed radiofrequency, cryoneurolysis, and sacral modulation have been promoted. Coccygectomy should be assiduously avoided.

Pelvic floor prolapse

Pelvic prolapse may be noted in as many as 50% of multiparous women. The cause of pelvic prolapse is believed to be a multifactorial combination of aging, trauma, devascularization, changing collagen content, and lowered estrogen levels. Pelvic floor prolapse in young premenopausal patients has been associated with decreased collagen content compared with normal controls. Pop-Q examination and visualization are the gold standard for diagnosis; MRI defecography may be helpful in some situations. Organ prolapse may include the anterior compartment: cystocele, uterine prolapse, and enterocele. Rectocele may cause issues with obstructive defecation. Rectal prolapse can be associated with mucous discharge and incontinence. Surgical treatment has been the gold standard for most gynecologic, urologic, or gastrointestinal prolapse, although use of a pessary may relieve symptoms for anterior pelvic floor prolapse in some patients. The causes and treatment options for rectal prolapse are discussed elsewhere in this issue.

Infectious Causes

Gynecologic diseases, such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, HIV-AIDS, trichomoniasis, vaginitis, and genital herpes, may cause pelvic pain. Symptoms include bloody or malodorous vaginal discharge, urinary symptoms, dyspareunia, and cervical motion tenderness on examination. Objective findings may be minimal and reinfection without partner treatment is common. Treatment may be delayed if there is not a high level of suspicion. Chronic infections may contribute to infertility.

Chronic Pain Syndromes

A substantial number of patients with CPP do not demonstrate objective findings. These patients often undergo substantial workup and may have had transient improvements from treatment, but they continue to have recurrent pain. In these patients, Janicki describes a chronic pain syndrome that involves the hypersensitization of nerve cells, increased role of the autonomic nervous system, and “windup” of the pain environment. Once patients experience this phenomenon, even minor pain stimulants can exacerbate or maintain the pain. Howard and colleagues describe pain mapping of the visceral organs using a blunt probe laparoscopically under conscious sedation. Treatment involves injection at pressure points.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree