INITIAL QUESTIONS IN THE KIDNEY TRANSPLANT RECIPIENT EVALUATION

At the present time, only a kidney transplant can restore renal function to patients with chronic kidney failure. The evaluation of the potential recipient of a kidney transplant is a process that requires close communication between the patient, the transplant team, and the referring nephrologist or dialysis center. Early in the evaluation process, some important issues should be answered for each patient (

Table 3.1). These include candidacy for transplantation, reasons why to get a transplant, timing and type of transplantation, and the steps to follow in the process to get ready for kidney transplantation.

The number of patients requiring treatment for chronic kidney failure continues to increase yearly (

1). Many more patients are now considered as candidates for kidney transplantation and are referred to transplant centers (

2,

3). Guidelines for the evaluation of kidney transplant candidates have been published by the American Society of Transplantation and the European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association (

4,

5,

6). These guidelines incorporate valuable information about the transplant evaluation process. Different transplantation centers do have variations in their approach to the evaluation of transplant candidates. Ultimately, the evaluation of kidney transplant recipients needs to assess the benefits/risks of surgery and long-term immunosuppression for each individual patient. The presence of kidney failure makes the evaluation and care of these patients different from preoperative evaluations in the general population (

5). In addition, although the comorbidities of kidney transplant candidates now are greater than in the past, patients accepted for transplantation and on the waiting list are generally healthier than other patients with chronic kidney failure (

5,

7,

8).

Candidacy for Kidney Transplantation: Who can get a transplant?

Kidney transplantation is a treatment reserved for irreversible kidney failure. Recipients must have an acceptable

surgical risk and be able to take immunosuppressive medications. Transplantation of a kidney from a deceased or living donor uses a precious and a scarce resource. Kidney transplantation from a living donor also carries a small but possible risk to the donor (

3,

9). Kidney transplantation procedures should only be performed when there is a reasonable expectation of success measured both in life expectancy and graft survival. Absolute contraindications to kidney transplantation include short life expectancy, high likelihood of early graft loss, metastatic cancer, active infection, and advanced untreatable medical problems. In addition, concerns about inability to care for the transplant due to substance abuse, emotional/psychiatric issues, noncompliance, or financial barriers need to be resolved before transplantation (

10).

The first step in the evaluation process is referral to a transplant center. Factors such as lower socioeconomic status, minority race, female gender, lower level of education, perceived discrimination, and obesity have been associated with less access to transplantation (

11,

12,

13,

14). Patients dialyzed in for-profit dialysis units also appear to have lower rates of referral for transplantation (

15). Efforts aimed at educating patients, referring physicians, and dialysis providers, as well as new mandates requiring evaluation of candidacy for kidney transplantation for all patients in the end-stage renal disease program, should continue in order to remove barriers to transplantation.

Benefits of Kidney Transplantation: Why Get a Transplant?

Both short-term and long-term patient and graft survival continue to improve for recipients of deceased donor kidneys or living donor kidneys (

2,

3,

16). Comparisons of mortality between transplant recipients and dialysis patients have to take into consideration that healthier patients with kidney failure are referred for transplantation while sicker and older patients remain on dialysis. Analysis of the U.S. Renal Data System (USRDS) database has shown that the mortality rate for patients listed for transplantation is one-half the mortality seen in all dialysis patients (

8). In the same analysis, patients receiving kidney transplant from a deceased donor had a survival advantage over wait-listed dialysis patients. Although recent advances in general medical care have led to improvements in survival for both patients on the transplant waiting list and recipients of a kidney transplant, long-term follow-up shows that kidney transplant recipients still have a large survival advantage over patients who remain on maintenance dialysis (

17).

In addition to the survival advantage, a functioning kidney transplant can prevent uremic complications and avoids the large volume fluctuations seen in dialysis patients. Health-related quality of life is better for transplant patients than for dialysis patients (

18). Costs per patient-year are lower for transplantation than for dialysis treatments (

19).

Timing of Kidney Transplantation: When to Get a Transplant?

Patients who undergo kidney transplantation preemptively (before starting dialysis) have the best patient and graft survival (

20,

21). After correction for donor and recipient variables known to affect transplantation outcomes, increasing time on dialysis (as compared with preemptive transplantation) is associated with progressive increases in mortality and death-censored graft loss after transplantation (

20). In recipients of living donor kidney transplants, increasing time on dialysis is associated with lower graft survival and increasing odds of rejection (

21).

A recent study examined the impact of time on dialysis on long-term outcomes for recipients of paired deceased donor kidneys and recipients of living donor kidneys. Increasing time on dialysis was the strongest independent modifiable factor reducing the 10-year graft survival in both groups (

22).

All patients with chronic kidney disease should be informed about the options for renal replacement therapy. Patients with chronic kidney disease stage IV (glomerular filtration rate [GFR] 15-29 mL/min) should be actively prepared for renal replacement therapy (

23). Preparation for preemptive transplantation should be pursued when possible. At present, patients should have a GFR less than 20 mL/min before they can start accumulating time on the waiting list for transplantation. Preemptive kidney transplants are more common for recipients of living donor kidneys (

24). Recipients of preemptive transplants are more likely to be white, working, covered by private insurance, and with a college degree (

24). Patients already on dialysis should be referred for transplantation as early as possible.

Transplant Selection: What Type of Transplant?

Patients with kidney failure can receive a kidney from a living donor or a deceased donor. The best transplant outcomes are observed with two-haplotype matches between siblings, followed by one-haplotype and zero-haplotype matches. Living unrelated donor kidney transplant recipients also have excellent results with outcomes at 5 years comparable or exceeding outcomes seen with transplantation from deceased donors (

3). The advantage of living donor transplantation is observed in most clinical scenarios, making it the preferred option for most patients (

25).

The total number of living donor transplants has been increasing by 12% per year since 1996, and the number of deceased donor transplants has increased by 2% per year (

26). In 2001, living donors made up over half of all donors, although deceased donors with two kidneys still accounted for more of the transplants performed (

3,

26). Explanations for the increases in the number of living donors include better outcomes of kidney transplantation, growth in the waiting list with associated increases in waiting time, and the introduction of laparoscopic nephrectomies with quicker recovery

times (

9). Although generally safe and with low morbidity and mortality, complications do occur with kidney donation, and mortality, renal dysfunction, and renal failure have been reported (

9,

27). All living kidney donors should have long-term medical follow-up.

One option to increase access of patients on the waiting list to transplantation is to accept donors with characteristics that may carry higher risks of graft failure or complications for the recipient. Donor characteristics of these “expanded donors” include medical/social history, cause of donor death, mechanisms of donor death, anatomy of the allograft, morphology on kidney biopsy, and functional profile (

28). Expanded criteria donor kidneys have a relative risk of graft loss greater than 1.7 and include kidneys from donors aged 60 years and older, and those 50 to 59 years of age with at least two of three conditions (cerebrovascular accident as cause of death, serum creatinine greater than 1.5 mg/dL, and history of hypertension) (

29). Transplantation of kidneys from donors with some of these characteristics is still associated with a significant survival benefit when compared with remaining on maintenance dialysis (

30).

Some patients with kidney failure and additional end-organ damage can be evaluated for multiorgan transplantation. In carefully selected patients, combined pancreas-kidney, liver-kidney, and heart-kidney transplantation can be associated with excellent long-term results (

3,

31). Combined kidney-lung transplantation is an option for a few selected patients (

32).

An increasing number of patients in the dialysis population have experienced loss of a primary kidney transplant. The loss of a primary kidney transplant is associated with high mortality. Repeat transplantation for these patients, however, is associated with a substantial improvement in 5-year mortality (

33). Although retransplantation is associated with a decrement in outcomes at all points, the magnitude of the differences has become smaller in recent years (

3,

34). Retransplant patients at higher risk for graft failure are those with high levels of panel-reactive antibodies (PRA) and previous graft survival time of less than 3 to 6 months who experienced immunologic graft losses (

34,

35). Matching and prevention of acute rejection can be associated with excellent long-term outcomes, even for retransplant patients in the high-risk groups (

34).

Transplant Evaluation Process: How Is the Transplant Evaluation Performed?

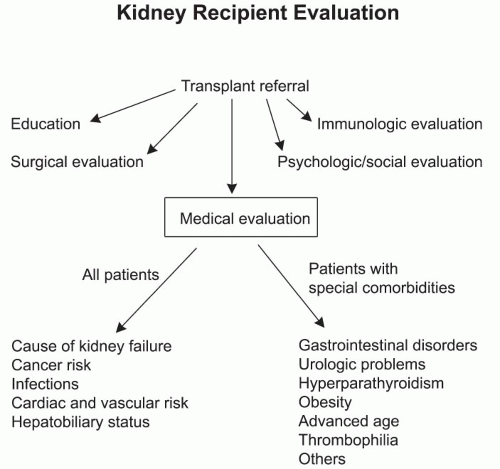

The evaluation process for transplantation can be divided into several areas: (a) patient education, (b) surgical evaluation, (c) medical evaluation, (d) psychological/social evaluation, and (e) immunologic evaluation (

Fig. 3.1).

Patient education involves the delivery of comprehensive yet clear information about kidney transplantation and its related issues, including benefits, risks, and complications to the potential transplant candidate (

5,

6,

10). Most patients treated with dialysis have very limited knowledge about transplantation (

36). Kidney transplant candidates frequently have unrealistic expectations about quality of life after transplantation (

37). The transplant team (transplant nephrologist and transplant surgeon, coordinators, social worker, dietitian, pharmacist, and other health care professionals) is a reliable source of information, and has the responsibility of guiding patients along the preparation for transplantation (

10,

37). Specific issues to address as part of the education process include current transplant results, transplant failure and rejections, complications, role of coexistent morbidities on transplant outcomes, and waiting times.

This is a good opportunity for education and advice about the importance of other aspects of their care, including compliance with dialysis treatments. Cigarette smoking contributes adversely to graft loss and death, and all smokers should be strongly encouraged to cease smoking prior to transplantation (

38). Involvement of family members at an early stage in the transplantation evaluation process can be extremely valuable (

10). Open communication with the referring physician and dialysis center also facilitates patient care.

Patients should be informed on the time estimates for completion of the evaluation process and placement on the waiting list. Issues related to potential living donor kidney transplantation should be discussed. Finally, patients need to understand that future changes in their health condition may prompt reassessment of their suitability for transplantation.

The surgical aspects related to transplantation, psychological and social issues relevant to the care of transplant recipients,

and the immunologic evaluation of kidney transplant recipients are discussed in other chapters.

Medical Evaluation

All transplant candidates should undergo a complete medical evaluation that includes a thorough history and physical examination. It is important to review all the information related to prior kidney disease and its treatment as well as other medical illnesses and prior surgeries. The review should also include information on the current functional status of the patient, dialysis care, health maintenance, medications, and relevant family history and review of systems. The physical examination should include all organ systems, with a special attention to any findings which may suggest active disease. The dialysis access (vascular or peritoneal), lower extremities, and peripheral pulses should be carefully examined. All transplant recipients should be up to date with their health maintenance, including age-appropriate screening tests. There is a significant variation among transplant centers on the extent of additional diagnostic tests required for their transplant candidates (

5,

6,

7).

Table 3.2 summarizes a list of diagnostic tests and evaluations performed in different transplant centers. The medical pretransplant evaluation of all kidney transplant recipients should address the areas of primary cause of kidney failure, cancer risk, infections, cardiovascular disease, and hepatobiliary status. Special comorbidities applying to some patients include gastrointestinal disease, prior history of urologic problems, hyperparathyroidism, obesity, advanced age, thrombophilia, and other chronic medical problems (

Fig. 3.1).

PRIMARY CAUSE OF KIDNEY FAILURE AND RISK FOR RECURRENT DISEASE

Disorders leading to kidney failure and need for transplantation include diabetes, glomerular diseases, vascular diseases/hypertension, tubular interstitial diseases, cystic diseases, neoplasms, and diseases of the transplant kidney (

32). Most kidney diseases can recur in the allograft (

Table 3.3). Some reports have noted that patients with recurrent disease have a relative risk of 1.9 for graft failure compared with recipients without recurrence (

39). Accurate determination of the impact of recurrent disease upon graft survival depends on accurate diagnosis of both the primary disease in the native kidneys and histologic confirmation of its recurrence in the allograft (

40). In addition, the impact of recurrent disease increases over time and will likely become more important as a cause of graft loss as overall graft survival rates continue to improve (

41). This section examines kidney disease and recurrence risk from the perspective of the pretransplant evaluation.

Diabetes is now the most common cause of kidney failure in the United States (

42). Short-term graft survival for patients with diabetes is excellent and comparable to other diagnoses (

32). Long-term graft survival, however, is lower for patients with diabetic nephropathy (

2,

32). The histologic recurrence of diabetic nephropathy in the allograft appears to be more rapid in recent years (

43).

Kidney transplantation is associated with higher patient survival compared with dialysis for patients with diabetes (

8,

44). Although death rates posttransplantation are highest

among recipients with diabetic kidney disease, diabetic recipients also derive the greatest benefit from transplantation in terms of relative increases in survival as compared with dialysis (

3,

8). The additional benefits associated with transplantation of the kidney and pancreas in diabetic patients are discussed in the chapter on kidney and pancreas transplantation (

45,

46).

For patients with kidney failure secondary to glomerular diseases, posttransplantation recurrence is the third most frequent cause of long-term graft loss at 10 years after chronic rejection and death with a functioning graft (

41).

Focal segmental glomerular sclerosis (FSGS) recurs in 20% to 30% of transplant recipients and carries a 40% to 50% risk of graft loss for those patients with recurrent disease. Risk factors for recurrence include aggressive initial course of the disease, younger age at onset, race (non-African American), and history of recurrence in a previous transplant (

47,

48,

49,

50). The presence of a circulating factor in serum has been associated with recurrent disease in some reports (

51). Preoperative plasmapheresis may be effective in preventing posttransplant recurrence in some children (

52). Although there are concerns about higher likelihood of FSGS recurrence for living kidney donor recipients, death-censored graft survival is significantly better for zeromismatched living donor kidney recipients as compared with human leukocyte antigen-(HLA-)mismatched donations or transplants from deceased donors (

53).

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis type 1 occurs in 20% to 30% of recipients and is associated with a high incidence of graft loss (

36,

54).

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis type 2 typically recurs after transplantation (50% to 100%), but shows slow progression with kidney failure in a small number of patients with recurrent disease (

40,

55).

IgA nephropathy recurs in 40% to 50% of patients with long-term follow-up (

56,

57,

58,

59). Graft loss occurs in about one-third of patients with recurrent disease (

5,

40). Clinical expression of recurrent disease and graft losses increase with longer follow-up (

40,

55). Recurrence appears to be more common in younger patients (

60). Although recurrence also appears to be more frequent for living donor kidney recipients, graft survival is not reduced (

59,

60). Administration of fish oil may have a beneficial role in IgA recurrence (

61).

Henoch-Schönlein purpura recurs in 20% to 30% of patients (

5,

40). Short duration of the original disease and recent disease activity may increase the likelihood of recurrence. It is generally recommended to delay transplantation until the disease is clinically quiescent (

5,

62).

Membranous nephropathy recurs in about 20% to 30% of patients, with close to half of patients with recurrent disease experiencing graft loss at 10 years of follow-up (

63).

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) recurs in close to 30% of patients and is associated with graft survival rates of 33% for those patients with recurrent disease (

64). Recurrence generally occurs early after transplantation (

65). Factors associated with recurrence include older age at onset of HUS, shorter interval between onset of HUS and kidney failure or transplantation, and the use of living donor kidneys and calcineurin inhibitors (

64).

Although earlier reports noted that recurrence of

systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) after transplantation was rare, studies that are more recent have observed recurrences in up to 30% of patients (

66,

67,

68). Graft loss due to recurrent lupus nephritis, however, is rare (

68). It is generally recommended that clinical manifestations of lupus be quiescent before transplantation. Duration of dialysis prior to transplantation and serologic parameters do not predict disease recurrence (

66). Transplant candidates with SLE have an increased frequency of acute rejection and thrombotic events (

66). It is recommended to evaluate for the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with SLE before transplantation.

Anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) disease recurs in 10% to 25% of patients after transplantation (

5,

35). Recurrence is rare after disappearance of anti-GBM antibodies, although late recurrences can occur (

40,

69).

Renal vasculitis associated with anticytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) recurs in 17% of patients (

70). The subtype of disease (Wegener’s granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, or crescentic glomerulonephritis), duration of dialysis, or the presence of a positive ANCA at the time of transplantation do not predict disease recurrence (

70). Patient and graft survival for recipients with ANCA vasculitis is similar to that for other transplant patients (

70).

Scleroderma (progressive systemic sclerosis) recurs and causes graft loss in about 20% of cases (

5,

71). Patient and graft survival is comparable for transplant recipients with scleroderma and SLE (

71). Patients with advanced pulmonary, cardiac, or gastrointestinal involvement have a high risk for adverse outcomes after transplantation.

As patients with

sickle cell disease live longer, more of these patients are being treated for kidney failure. The 1-year kidney transplant survival for patients with sickle cell disease is similar to that seen in African American patients with other types of kidney diseases (

72). The long-term survival is comparatively diminished (

72). There is, however, a trend toward better patient survival with kidney transplantation relative to dialysis.

Alport’s syndrome is not associated with recurrence after transplantation of a histologically normal kidney. Transplant recipients can develop anti-GBM antibodies after exposure to the basement membrane of the transplanted kidney (

5,

73). Allograft anti-GBM nephritis is rare, and the patients with Alport’s syndrome have patient and graft survival comparable to other transplant patients (

73).

Primary oxaluria is a rare autosomal recessive metabolic disease caused by deficient activity of the hepatic enzyme alanine: glyoxylate aminotransferase (AGT), which often progresses to kidney failure (

5). Liver transplantation restores the deficient enzyme activity. Kidney transplantation alone is followed by the almost universal recurrence of oxalosis with consequent urolithiasis and nephrocalcinosis. Patients without significant systemic oxalosis and some residual AGT activity can be considered for kidney transplantation

alone with intense medical management (

74). Patients receiving combined liver-kidney transplantation for systemic oxalosis have superior death-censored graft survival compared with oxalosis patients receiving kidney transplants alone from a deceased donor or a living donor (

75).

In patients with

cystinosis, kidney transplantation restores the normal lysosomal transport system for cystine effux in the renal tubular cells, and there is no recurrence of kidney disease after transplantation (

76). Transplantation has excellent results and should be considered early in the course of cystinosis (

77).

Fabry’s disease is an X-linked disorder due to deficiency of the lysosomal enzyme α-galactosidase. Although accumulation of glycosphingolipids recurs in the kidney after transplantation, the 5-year results after kidney transplantation for patients with Fabry’s disease are excellent and comparable to other transplant recipients (

78). Progression of cardiovascular complications and infections are the main factors affecting long-term outcome (

78,

79). Some transplant candidates with Fabry’s disease have an increased risk for allograft thrombosis associated with activated protein C resistance and benefit from anticoagulation (

80,

81).

Kidney transplant recipients with

amyloidosis have higher mortality than other transplant recipients (

82,

83). Although both primary and secondary amyloidosis can recur in the allograft, graft loss due to recurrence is rare (

83,

84). Long-term outcome is dependent on the manifestations of the systemic disease (

5). Colchicine can be effective in preventing kidney transplant amyloidosis in recipients with familial Mediterranean fever (

83).

All

paraproteinemias can recur in the allograft. Multiple myeloma has a recurrence rate of 67% after renal transplantation, but recurrence does not necessarily lead to graft failure (

85,

86). Light chain deposition disease recurs in about half of patients, but a few selected patients may have prolonged graft survival (

87,

88). Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia also recurs in a large percentage of patients (

5,

89).

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (AD-PKD) does not recur in the allograft. Transplant recipients with AD-PKD have the best short- and long-term outcomes after transplantation (

3). A careful assessment of any potential extrarenal complications of AD-PKD should be performed prior to transplantation.

BK virus-associated nephropathy (BKV-AN) has become an important cause of renal graft loss in recent years (

90). Retransplantation appears to be a viable option for patients who have lost a prior kidney to BKV-AN, especially if there is no evidence of active polyomavirus replication at the time of repeat transplantation (

91,

92).

CANCER RISK

The overall risk of cancer is increased for patients on dialysis and kidney transplant recipients (

19,

93,

94,

95,

96). The main premise of cancer screening in kidney transplant recipients is to reduce mortality and morbidity by detection of cancer in early and less aggressive stages than advanced cancer. Some have suggested that cancer screening is not effective in the dialysis population and may not yield benefits in average kidney transplant recipients (

97,

98). Interpretation of the effectiveness of cancer screening in transplant recipients involves several special considerations. Kidney transplant recipients are generally healthier than other patients with kidney failure (

5). Immunosuppression increases the risk of cancer (

94,

95). Malignancies tend to have a more aggressive course in kidney transplant recipients (

99). Finally, kidneys from living donors or deceased donors are a very valuable and a scarce resource, and there is a responsibility to maximize their use and also benefit the intended recipient. Based on these considerations, most kidney transplant programs are very careful in assessing the risk of cancer in potential transplant recipients.

Evaluation of the cancer risk begins with a complete history and examination. Factors such as smoking and prior immunosuppression increase the risk of cancer after transplantation and should be addressed in the pretransplant evaluation (

100,

101). Age-appropriate cancer screening is recommended including pelvic examination and pap smears for female patients, mammographies for females over 40 years of age (or with family history of breast cancer), colorectal screening for patients over 50, and digital rectal examination and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) for men over 50 with a life expectancy of more than 10 years, or for younger men with a positive family history of prostate cancer (

5,

6). Total skin examination, clinical breast exams, and examination of the testes also provide valuable information.

The risk of cancer of the kidney and the urinary tract is especially increased in the dialysis population and relatively more in younger patients (

93,

102). The risk of kidney cancer is raised in all categories of renal disease but particularly for patients with toxic, infective, and obstructive uropathies (

93,

102). Duration of dialysis and acquired cystic disease predispose to the development of renal cancer (

103). Prospective renal sonography has revealed the presence of previously undiagnosed renal cancers in 3.4% of prospective transplant recipients (

104). Some transplant programs recommend screening for renal cancer of all patients before kidney transplantation.

A special circumstance is presented by patients with a prior history of cancer but no evidence of disease activity and who desire a kidney transplant. As immunosuppressive therapy may facilitate the growth of residual cancers, the benefits of transplantation for patients with prior history of cancer need to be interpreted with consideration of the risks of cancer recurrence. Much of the information in this area comes from the work of the late Dr. Israel Penn, who established the Cincinnati Transplant Tumor Registry (now the Israel Penn Transplant Tumor Registry [IPTTR]) (

85). Reports from the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Association have also provided valuable information (

105). The type and extent of the prior cancer and the waiting time between cancer treatment and transplantation

appear to be the most important factors in determining the likelihood of cancer recurrence after transplantation (

85). Recently, it has also been reported that patients with diagnosis of cancer made after initiation of dialysis have a higher incidence of cancer recurrence than patients with cancer diagnosed before reaching kidney failure (

105).

Recurrence rates of cancer after transplantation range from 5% to 21% depending on the source of data (national registry versus voluntary reporting) (

85,

105). More than half of all malignancies recurring posttransplant and reported to the IPTTR have occurred in patients treated for cancer within 2 years of transplantation, one-third in patients treated 2 to 5 years before transplantation, and the rest in patients treated for cancer more than 5 years before the transplant (

85). A 2-year waiting period is recommended for most cancers (

85).

Table 3.4 lists some of the most common cancers reported to recur after renal transplantation.

As previously noted,

renal cancers are very important in the dialysis population. No specific waiting time is recommended for small (less than 5 cm) renal tumors discovered incidentally. The recurrence rate of other renal cancers is about 27%, and a 2-year waiting time is recommended after treatment and prior to transplantation (

85). Large, symptomatic, and invasive renal cancers may warrant longer waiting times. Appropriate evaluation, including imaging, is recommended before transplantation to ensure that the patient remains free of recurrence (

5).

Wilms tumors recur in about 13% of patients, and risk factors for recurrence include incomplete tumor removal and abdominal metastasis (

85,

106). There is a high mortality in patients with recurring disease and a 2-year waiting period is recommended prior to transplantation (

85).

Bladder cancer is particularly common in the dialysis population (

93,

102). Patients with bladder cancer

in situ or noninvasive papillomas tend to have a low risk of recurrence and do not require a waiting period (

107). Other bladder cancers recur in about one-third of patients, and a 2-year waiting period is recommended (

85).

Malignant melanomas recur in 21% of patients, and those patients with recurrent disease usually die from their melanoma (

107). Patients with melanoma

in situ and very thin melanomas can probably undergo transplantation after a 2-year waiting period (

108). Other patients treated for melanoma should probably wait 5 years before proceeding with transplantation (

85).

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access