Fig. 22.1

Abdominoperineal excision specimen for low rectal cancer demonstrating the peritoneal reflections (marked by the blue lines) at the anterior (a) and posterolateral (b) aspects. CRM circumferential resection margin

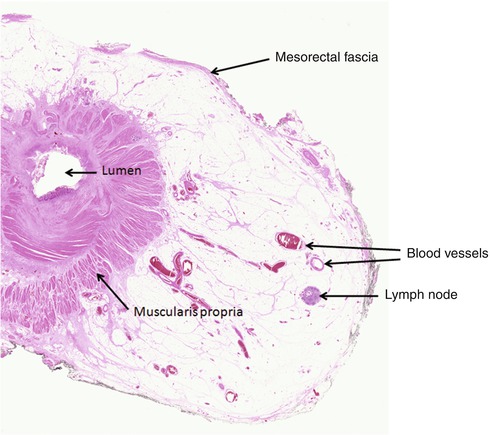

Fig. 22.2

Part of a haematoxylin and eosin-stained section from a whole mount rectal cancer block demonstrating the condensed fibrous tissue of the mesorectal fascia at the circumferential resection margin. Also demonstrated are blood vessels and a lymph node within the mesorectal fat, both of which are important routes of tumour dissemination

Anterior resection specimens for rectal cancer contain a variable amount of mesorectum depending on the position of the tumour and the quality of the surgical dissection. There is also marked variation in the overall volume of the mesorectum and the height of the peritoneal reflections between individuals. During the operation, the surgeon should attempt to sharply dissect immediately outside the mesorectal fascia in the so-called holy plane of TME surgery described by Heald [5]. This ensures that the mesorectum is removed as an intact package that contains the entire primary tumour along with all possible routes of metastasis. The outer non-peritonealised surface of the specimen forms what is termed the CRM, a surgically created margin that should be extensively covered with mesorectal fascia if the dissection has been performed in the correct tissue plane.

Tumour involvement of the CRM, defined as tumour at or within 1 mm of the margin, is a poor prognostic feature and is strongly linked to local disease recurrence [6–10]. The method of involvement may be by direct spread or tumour deposit or within a vessel or nerve bundle with all showing a similarly poor prognosis [11]. A tumour deposit contained wholly within a lymph node may have a lesser risk, but this has yet to be proven. Others have suggested that tumour within 2 mm of the CRM is associated with a worse outcome, but sufficient data does not currently exist to support this position [12]. Prior to the description of TME surgery, the rates of CRM involvement were as high as 36 % [6] and varied markedly between individual surgeons [11]. The introduction of TME over recent years has been shown to substantially reduce the rate of local disease recurrence and improve survival, initially in single-centre series [13, 14], followed by large-scale population series and clinical trials [15–17]. A recently published UK trial showed CRM involvement rates to be as low as 8 % in the latter patient cohort with an increase in the median distance between the tumour and the CRM from 5 to 8 mm over the duration of the study [18]. It is believed that a major factor in the success of TME surgery is the marked reduction in CRM involvement and tumour perforation associated with the technique [11]. However, the more advanced tumours may still extend to within 1 mm of the CRM or even breach the mesorectal fascia, and therefore, TME surgery on its own will not result in complete resection of the tumour. Surgeons may therefore attempt to perform a more extensive operation removing additional extra-fascial tissues or organs en bloc or more frequently use preoperative therapy to attempt to shrink the tumour into a surgically resectable state. Radiologists are now very good at predicting tumour involvement of the CRM using MRI [19, 20] and are therefore critical in selecting patients for neoadjuvant radiotherapy.

TME/anterior resection specimens for rectal cancer should be carefully examined and dissected by pathologists to ensure that all the important features are identified and described prior to irreversible slicing of the specimen. A meticulous and consistent approach is required to ensure that nothing is forgotten. We recommend the dissection protocol developed in Leeds [21] that has been adopted into the United Kingdom Royal College of Pathologists dataset for colorectal cancer [1]. It is important that the specimen is received intact and unopened, preferably in the fresh state, as any disruptions or incisions may impair the assessment of the CRM. On a fresh intact specimen, the CRM should be bound by mesorectal fascia, which appears as a shiny smooth layer that often becomes dulled and opaque after formalin fixation (Fig. 22.3). If the dissection extends as low as the prostate gland in males, an additional layer of fascia, the fascia of Denonvilliers, may also be noted [22].

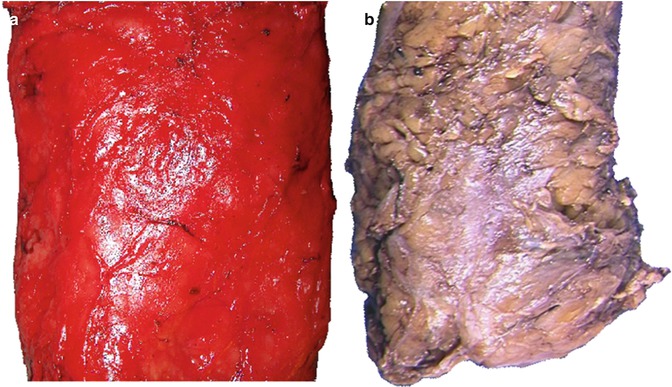

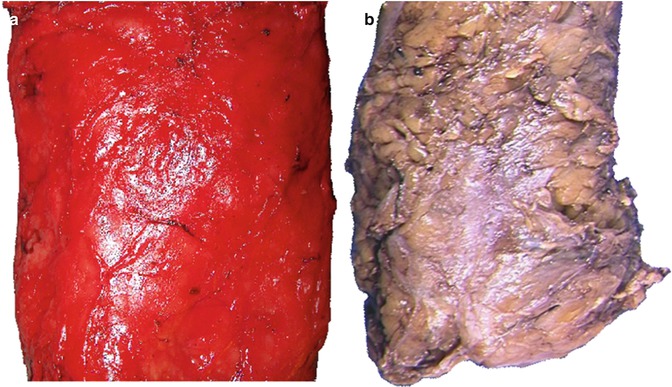

Fig. 22.3

The mesorectal fascia which appears as a shiny covering in the fresh specimen (a) and becomes a dull opaque colour after formalin fixation (b)

An assessment by the pathologist of the integrity of the surface of the specimen forms an important component of the assessment of the quality of surgery that must be fed back to the surgical team. A three-point grading system was initially developed for the MRC CLASICC trial [23] and has subsequently been shown to predict CRM involvement, local recurrence and patient survival in both small series [24–26] and larger multicentre studies [18, 27]. The recommended mesorectal grading system is described in Table 22.1.

Table 22.1

Three-point grading system for the assessment of the plane of mesorectal dissection in TME/anterior resection specimens for rectal cancer

Grade | Short description | Long description |

|---|---|---|

Mesorectal plane | Good surgery | Intact smooth mesorectal surface with only minor irregularities. Any defects must be no deeper than 5 mm. No coning of the specimen distally. Smooth CRM on slicing |

Intramesorectal plane | Moderate surgery | Moderate bulk to mesorectum but irregularity of the mesorectal surface. Moderate distal coning. Muscularis propria not visible with the exception of levator insertion. Moderate irregularity of CRM |

Muscularis propria plane | Poor surgery | Little bulk to mesorectum with defects down onto the muscularis propria and/or very irregular CRM. It includes infraperitoneal perforations |

It is helpful if the specimen is photographed at this stage to form a permanent record of the plane of surgery (Fig. 22.4). Digital images should be taken of the front and back of the specimen alongside a metric scale, with additional close ups of any significant mesorectal defects or perforations. These images should be stored in a departmental archive and can be used to facilitate feedback to surgeons in multidisciplinary team meetings and utilised for subsequent research/audit. Feeding back the plane of surgery in such a way to the operating team has been shown to improve the planes of dissection over time leading to a reduction in CRM involvement, which should ultimately improve patient outcomes [18].

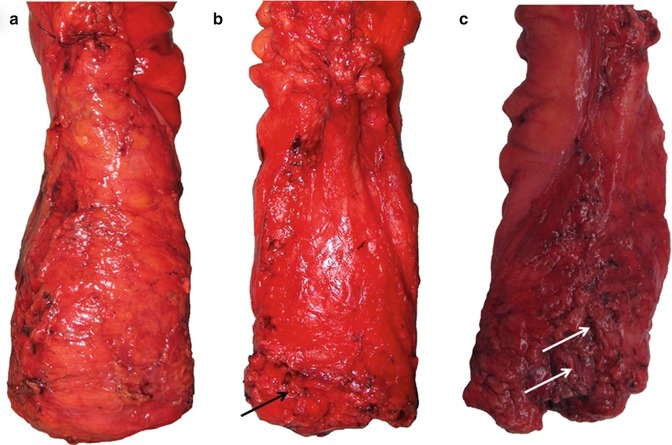

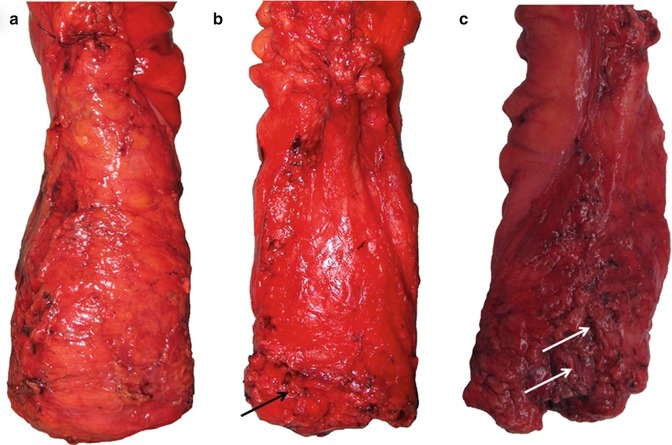

Fig. 22.4

Photographic documentation of the posterior surfaces of three anterior resection specimens showing good examples of the mesorectal plane (a), intramesorectal plane (b) and muscularis propria plane (c). Mesorectal defects are highlighted by arrows, which extend down to expose the muscularis propria in specimen C

Perforations, defined as a communication between the surface of the specimen and the lumen of the bowel, should similarly be documented in the report. Tumour perforations above the peritoneal reflections risk intraperitoneal recurrence and are associated with a poor prognosis [28, 29]. Under TNM staging rules, these tumours should be classified as pT4 [30]. However, infraperitoneal perforations are much more frequent and can occur at the time of surgery, often at the anterior aspect where the mesorectal thickness is at a minimum or in the area of the puborectalis. These surgical failures are not strictly pT4 tumours under TNM staging, but due to the high risk of local recurrence and reduced survival [31], we feel that they should be classified as pT4 on the basis of a poor anticipated prognosis.

Following a detailed macroscopic description, the specimen should be inked over the entire area of the CRM to allow for accurate histological measurement between the tumour and this margin. There should be no confusion between the CRM and the peritoneal surface as tumour involvement of both of these structures has different potential sequelae. Peritoneal disease, as described above, risks intraperitoneal recurrence in the abdominal cavity, whereas CRM involvement risks local pelvic recurrence. After inking, the tumour segment should undergo serial cross-sectional slicing at 3–5 mm intervals. The slices should be laid out in order and photographed to record the relationship between the tumour and the CRM and also to provide additional evidence for the plane of surgery. These images can be very useful for comparing to the radiological appearance of the tumour if any discrepancies arise. Ideally a minimum of five tumour blocks should be taken and at least one of these must demonstrate the tumour closest to the inked CRM. The pathological report must include a comment as to whether or not the CRM is involved by tumour so that the patient may be offered further adjuvant therapy, if appropriate, to reduce the chances of local disease recurrence. The distance between the tumour and the closest CRM to the nearest millimetre should be fed back to radiologists to allow them to audit the accuracy of their preoperative prediction of CRM status. If the MRI scan predicted a clear margin but the resection specimen shows evidence of tumour involvement, then it is helpful if the pathologist can indicate why this is so. Possible reasons include a tiny tumour deposit at the margin which would not be visible on MRI or alternatively that the area of CRM involvement relates to a region where the TME plane was not followed by the surgeon. In post-neoadjuvant therapy cases, it is also helpful for the pathologist to indicate whether any fibrosis extends beyond the tumour towards the CRM for correlation with the pre-radiotherapy MRI scan.

Reporting Abdominoperineal Excision (APE) Specimens for Low Rectal Cancer

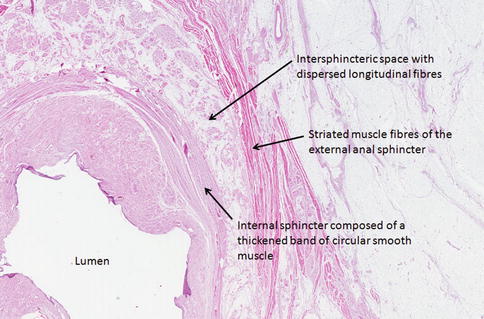

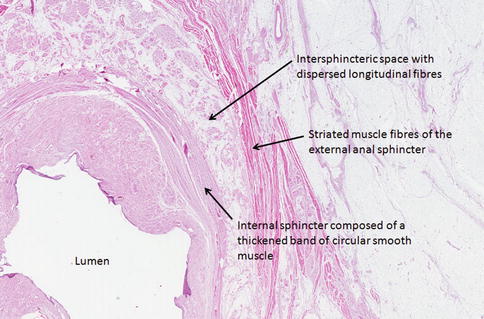

APE of the rectum and anus is frequently utilised for the surgical treatment of advanced low rectal tumours (within 6 cm of the anal verge) where anatomical reconstruction is not possible or for reasons of poor predicted functionality. The specimen should include the rectum and mesorectum, as for a TME specimen, in continuity with the anal canal and a portion of perineal skin resulting in a permanent stoma for the patient. The anal sphincter muscles and levator ani muscles may be removed en bloc with the specimen depending on the radicality of the operation. The internal anal sphincter is a thickened continuation of the inner circular layer of smooth muscle from the rectal muscularis propria. Occasionally dispersed longitudinal fibres may also be seen. Immediately outside this layer the striated muscle fibres of the external sphincter are seen (Fig. 22.5). Above the sphincter complex, some of these striated fibres fuse with the levator ani muscles of the pelvic floor.

Fig. 22.5

Haematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue section through the anal sphincters demonstrating the internal and external sphincters separated by the intersphincteric space

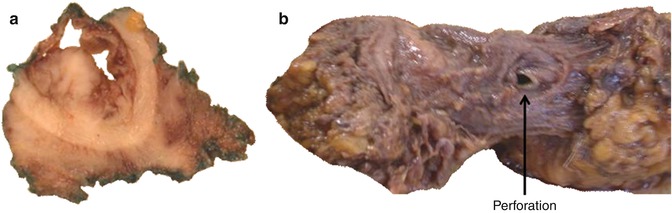

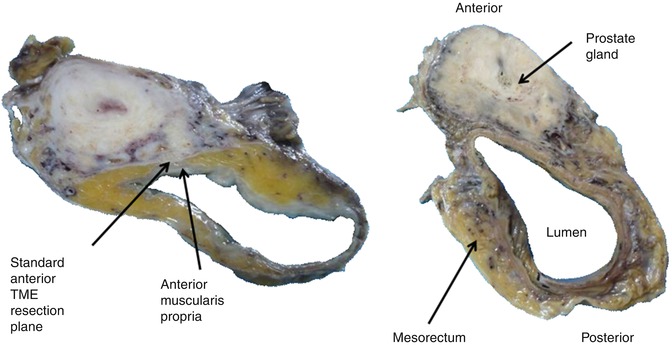

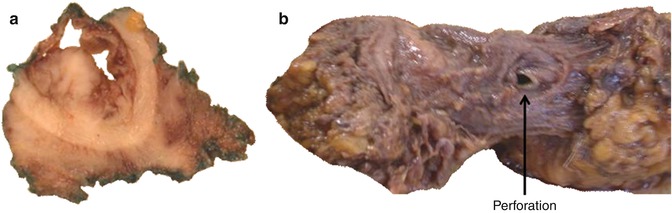

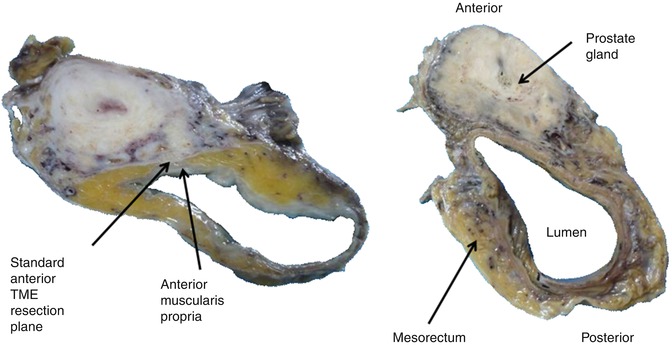

Approximately 25 % of operations for primary rectal cancer will result in an APE [32], although there is wide variation in the frequency of this operation, which is considered by some to be unacceptable [33]. For this reason it has been proposed that APE rates themselves may be used as a surrogate marker of surgical quality. Obviously to provide a fair and meaningful comparison, these rates should be adjusted for factors such as tumour height [34] and specialist referral practice at the centre. In general, however, lower APE rates are considered to be a marker of good practice. This is because APE surgery for low rectal cancer is well recognised to be associated with poorer patient outcomes when compared to anterior resection for higher rectal tumours [2, 29, 35]. As stated in the section above, there is a natural reduction in mesorectal tissue volume when moving from the middle of the mesorectum down towards the commencement of the sphincters. For this reason, there is less protective tissue around lower rectal tumours when following the standard mesorectal fascial plane, which accounts for the higher CRM involvement rate with APE surgery [2]. Also, because much of the perineal dissection during standard APE is performed under limited visualisation in the lithotomy position, surgeons often deviate into the wrong tissue plane which further increases the chances of an involved margin and may also result in an intraoperative perforation (Fig. 22.6). As has previously been stated, the most risky area for both CRM involvement and perforation is at the anterior aspect of the specimen where the mesorectum often reduces to a negligible amount [3, 36]. For this reason, en bloc prostatectomy or resection of the posterior vaginal wall may be performed in cases with advanced anterior tumours in order to protect the anterior CRM (Fig. 22.7).

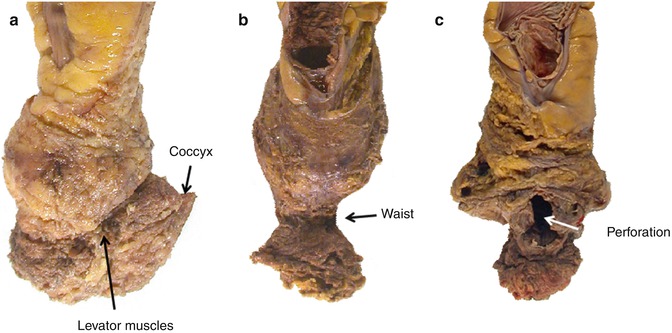

Fig. 22.6

Two examples of APE surgery performed in the wrong tissue planes. One specimen shows approximately one third of the circumferential resection margin being formed by submucosa resulting in a margin positive pT2 tumour (a) and the second shows a classic anterior intraoperative perforation at the level of the waist (b)

Fig. 22.7

Cross-sectional slices from two separate APE cases with en bloc prostatectomy showing the negligible amount of mesorectal tissue often seen between the anterior muscularis propria and the standard TME resection plane

Recent research has demonstrated improved clinical outcomes with more radical techniques termed extended APE and abdominosacral resection [37–40]. These procedures involve en bloc resection of the levator ani muscles along with the mesorectum and anal canal to create a more cylindrically shaped specimen as originally described by Miles [41]. Such ‘extra-levator’ surgery is usually carried out in the prone jackknife position to improve visualisation and has been shown to markedly reduce the rates of CRM involvement and intraoperative perforations compared to standard APE techniques [3, 36]. In turn this should improve outcomes towards those reported with anterior resection for higher rectal tumours.

Variables such as the mesorectal plane of dissection, presence of intraoperative perforations and CRM involvement should be reported for APE specimens in the same way as for TME/anterior resection specimens. However, in addition it has been proposed that the area of dissection around the sphincters should be separately graded [29]. This is of direct relevance to the rates of CRM involvement and patient outcomes because a beautiful mesorectal dissection will be offset by a perforation of the anal canal in the region of a low rectal tumour. The recommended anal canal/sphincter grading system is described in Table 22.2.

Table 22.2

Three-point grading system for assessment of the plane of anal canal/sphincter dissection in APE specimens for low rectal cancer

Grade | Short description | Long description |

|---|---|---|

Extra-levator plane | Good surgery | The specimen has a cylindrical shape due to the presence of levator ani removed en bloc with the mesorectum and sphincters. Any defects must be no deeper than 5 mm. No waisting of the specimen. Smooth CRM on slicing |

Sphincteric plane | Moderate surgery | The specimen is waisted and the CRM in this region is formed by the surface of the sphincter muscles which have been removed intact |

Intrasphincteric | Poor surgery | The specimen is waisted and includes deviations into the sphincter muscles, submucosa and complete perforations |

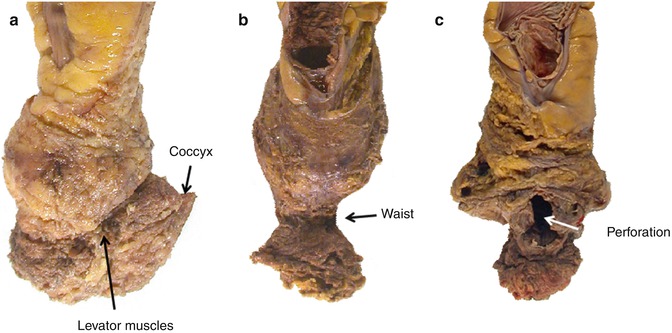

Photographs should be taken of the front and back of the whole specimen as for TME/anterior resection specimens and additional close ups of the anal canal/sphincter dissection are particularly useful for recording the plane of surgery in this area (Fig. 22.8).

Fig. 22.8

Photographic documentation of the anterior surfaces of three formalin-fixed APE specimens showing good examples of the extra-levator plane (a), sphincteric plane (b) and Intrasphincteric plane (c). The extra-levator specimen shows no waisting due to the levators and coccyx being removed en bloc with the mesorectum. The sphincteric specimen shows a classical surgical waist in the area of the sphincters but a good quality mesorectal dissection. The intramucosal/submucosal specimen shows evidence of significant mesorectal defects with a large anterior perforation through the tumour in the classic danger area

Data obtained from the Dutch TME trial, which included 373 APE specimens, demonstrated that two thirds of specimens were in the sphincteric plane and one third in the intrasphincteric plane [29]. None of the cases were scored as being in the extra-levator plane. In a multicentre European study comparing a large series of extra-levator APE to standard APE specimens, extra-levator APE was shown to remove significantly more tissue around low rectal tumours with a reduction in CRM involvement from 50 to 20 % and intraoperative perforations from 28 to 8 % [36]. The need to modify an APE operation to the extra-levator plane can be accurately predicted by the radiologist using preoperative MRI [42], and pathological feedback to confirm this prediction from the resection specimen is again essential.

Reporting Colon Cancer Specimens

The colon and its mesentery, the mesocolon, are both invested by a layer of visceral peritoneum to a variable degree. The ascending colon has a broad attachment to the posterior abdominal wall that varies in both size and shape. A layer of fascia exists at the deep aspect of the ascending mesocolon, and dissection outside of this layer forms the retroperitoneal surgical margin in a right hemicolectomy specimen if the dissection is carried out in the correct tissue plane. The transverse colon is suspended by a true mesentery, the transverse mesocolon, which is a substantial structure often not resected in its entirety due to technical difficulties with the dissection. Similar to the ascending colon, the descending colon has a broad attachment at its posterior aspect that merges into the sigmoid colon, which again has a true suspensory mesentery. Over recent years it has become clear that the surgical principles of mesorectal surgery should be extended to include operations for colon cancer. Surgical removal of the colon and mesocolon in an intact package containing the lymphatics, lymph nodes and blood vessels is essential to guarantee the complete removal of primary colonic tumours along with the routes of potential dissemination.

An in-depth knowledge of colorectal vasculature is essential to appreciate the technical aspects of the chosen operation and to identify the relevant arteries which run with the draining lymphatics from the tumour [43]. Branches of the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries supply the colon; however, there is often marked variation between individuals which influences the type and extent of resection performed. The embryological midgut is supplied by branches of the superior mesenteric artery and the major vascular ties that may be visible in right and transverse colon resection specimens include the ileocolic artery, the right colic artery and the middle colic artery. The right colic artery shows considerable variation and often represents a branch of the middle colic rather than arising directly from the superior mesenteric artery [44]. The inferior mesenteric artery and its branches supply the majority of the hindgut.

The lymphatic drainage of the colon and consistent surgical approaches for adequate clearance of colon cancer were first described in 1909 [43]. The colonic lymph nodes are often classified as being present in three distinct layers [45]. The first line of drainage comes from a series of paracolic lymph nodes that lie close to the muscle wall in proximity to the marginal artery of Drummond. Colon cancers tend to demonstrate a small degree of lateral spread throughout these paracolic nodes before turning centrally into the second layer of intermediate nodes, which follow the supplying arteries towards their origin. Finally, the third layer of central lymph nodes are situated at the origin of the supplying vessels at either the branching of the inferior mesenteric artery from the aorta on the left or the major branches of the superior mesenteric artery on the right.

An optimal colon cancer resection specimen should therefore include the tumour with an adequate portion of non-diseased colon on either side, along with the associated mesocolon containing the blood vessels with high ligation of the supplying vessels and the paracolic, intermediate and central lymph nodes in an intact peritoneal and fascial bound package with no significant intraoperative defects. Surgeons practising this type of surgery, known as complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation (CME with CVL), report very impressive outcomes when compared to standard techniques [44, 46]. The majority of the survival benefit is believed to be derived from preventing mesocolic defects or tearing in the tumour drainage area, which could shed tumour cells into the peritoneal cavity and therefore risk intra-abdominal recurrence. Keeping the mesocolon intact has been shown to be associated with a 15 % overall survival benefit at 5 years compared to specimens with significant defects down on to the muscularis propria [47]. This difference rose to 27 % in stage III disease when all cases have tumour in the mesocolic lymph nodes and mesocolic disruptions are at their most dangerous.

Additional survival benefits when performing CME with CVL are likely to be derived from the optimum nodal clearance. The technique has been shown to be associated with the removal of an additional 10–12 lymph nodes in two independent colon cancer series [48, 49]. The majority of these extra nodes are likely to be pericolic and intermediate ones associated with the removal of a greater length of colon. The greatest benefit may be derived by removal of the central nodes in cases with downstaging of an otherwise Dukes C2 case into a Dukes C1. The majority of cancers display lateral nodal spread of up to 10 cm on either side of the lesion before the major drainage pathway heads centrally along the supplying arteries. However, occasionally the degree of lateral spread along the pericolic lymphatics can be considerable, particularly in cases with extensive nodal disease and blockage of the central lymphatics [50]. Such advanced disease is likely to be already incurable and therefore CME with CVL is unlikely to significantly impact on overall outcomes in this group of patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree