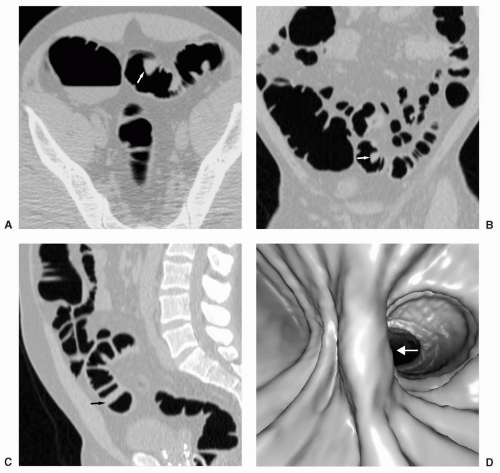

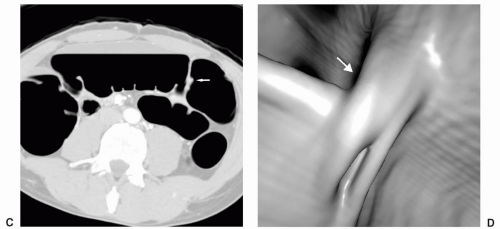

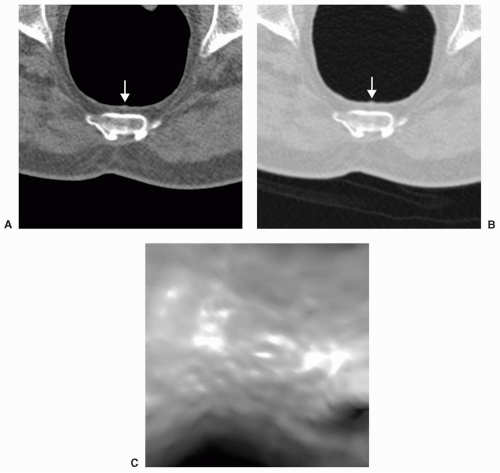

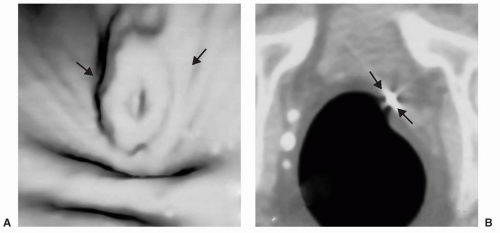

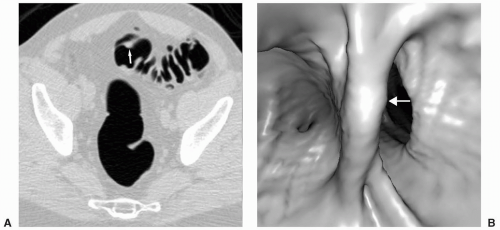

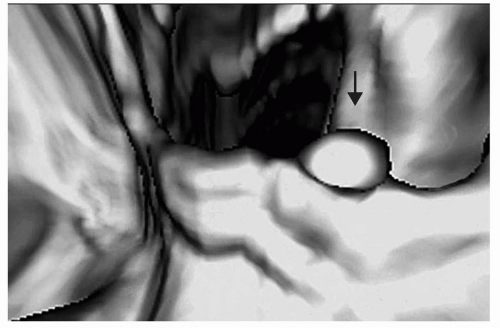

which usually tapers towards the anal verge. A rectal bar representing a more prominent longitudinal fold may be visualized along the anterior rectal wall (see Figure 6.9). A subtle, small pseudopolypoid lesion may be visualized along the posterior rectal wall on the 2D views at the point of anterior angulation of the rectum (see Figure 6.10).

TABLE 6.1 Pitfalls on Virtual Colonoscopy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

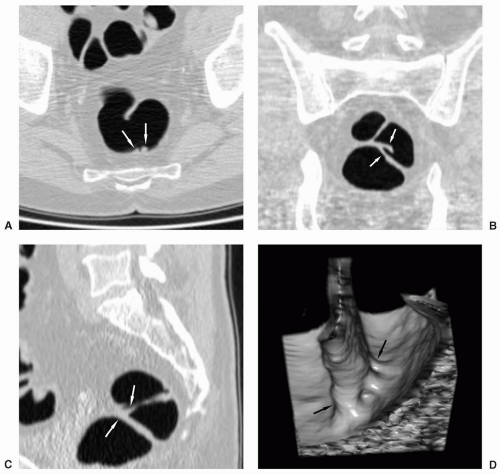

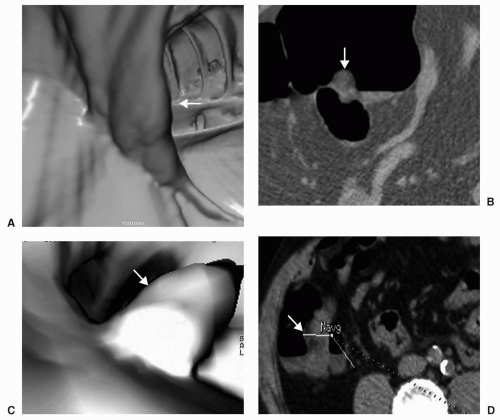

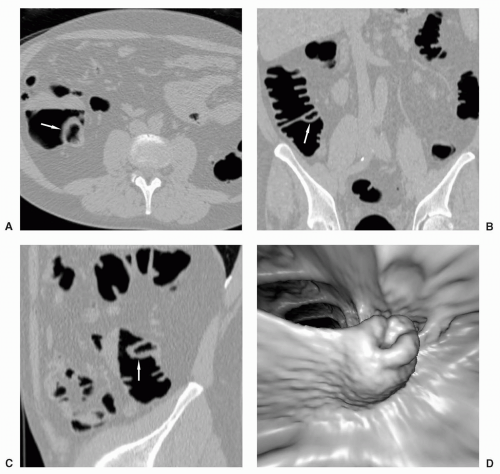

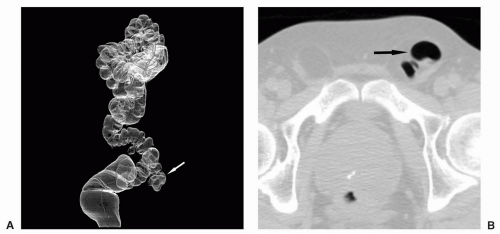

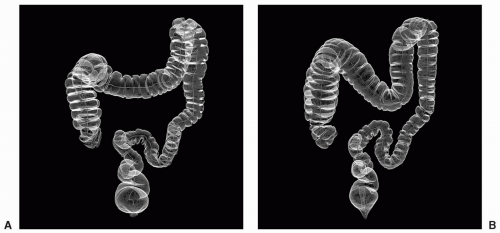

The appendix may be partially or completely inverted. Use of the older inversion-ligation technique for appendectomy, which is not often used currently, will result in an appendiceal stump that may simulate a polyp.12 If a potential polyp is identified on axial or 3D views, the reader should refer to the coronal or sagittal reformats to attempt to identify the appendix and the relation of the appendix, if present, to the lesion. History of prior appendectomy is important to obtain. An appendicolith is often also readily identifiable on 2D views. An inverted or intussuscepted cecal diverticulum has also been reported to simulate a pedunculated polyp on CT scan.13

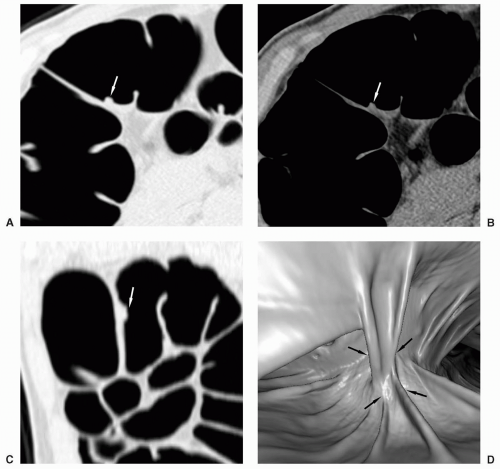

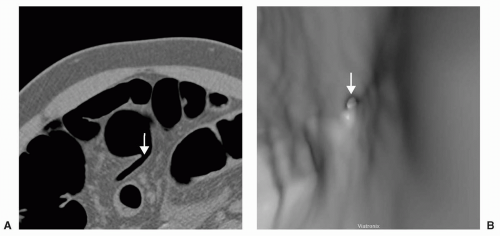

FIGURE 6.1 Bulbous Fold: Axial image (A) reveals a polypoid lesion on a fold. The 3D endoluminal view (B) demonstrates a bulbous fold. No polyp was identified on colonoscopy. |

FIGURE 6.4 Crossing Fold: Axial view (A) shows a small polypoid-appearing lesion on the middle of a fold. The 3D endoluminal view (B) shows an atypical fold that crosses the other haustral folds. |

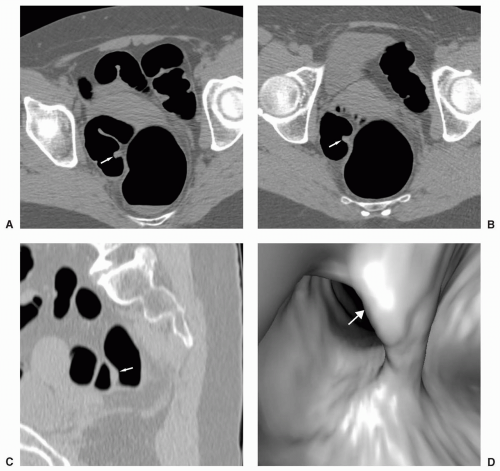

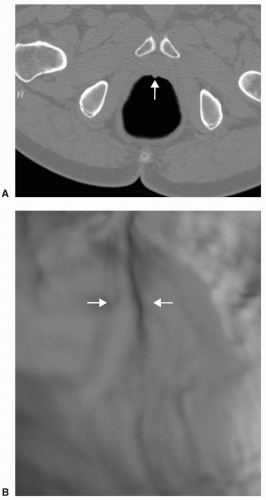

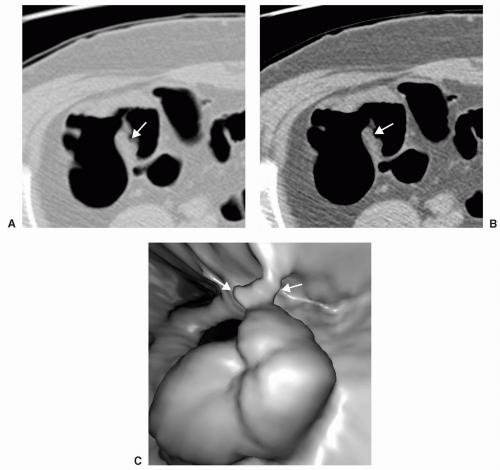

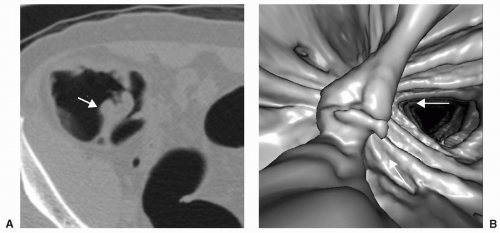

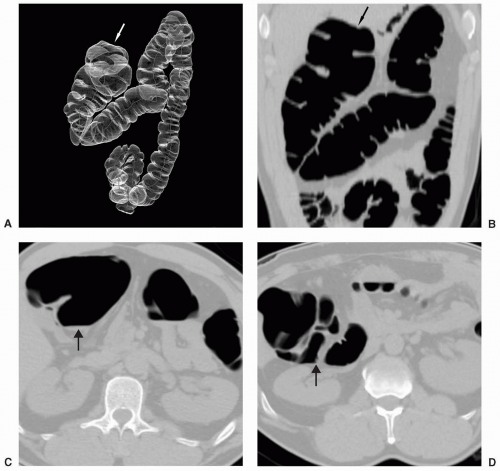

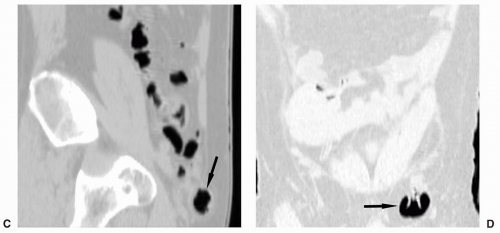

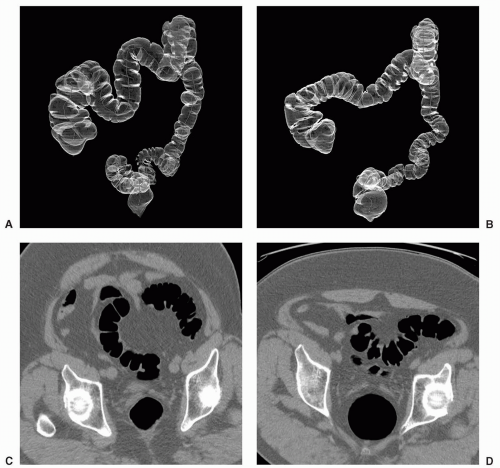

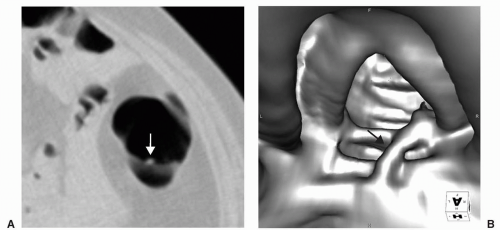

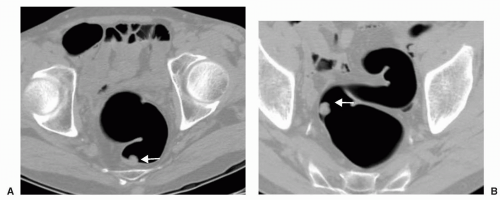

FIGURE 6.11 Normal Ileocecal Valve: Axial (A) and 3D endoluminal (B) views show the typical appearance of the ileocecal valve as rounded or ovoid with a central depression or pit. |

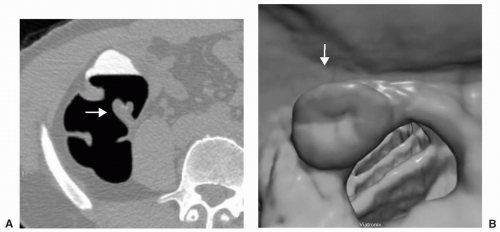

FIGURE 6.13 Polyp on Ileocecal Valve: The ileocecal valve is covered by colonic mucosa and polyps and carcinoma can develop on the valve. 3D endoluminal view shows a polyp on the ileocecal valve. |

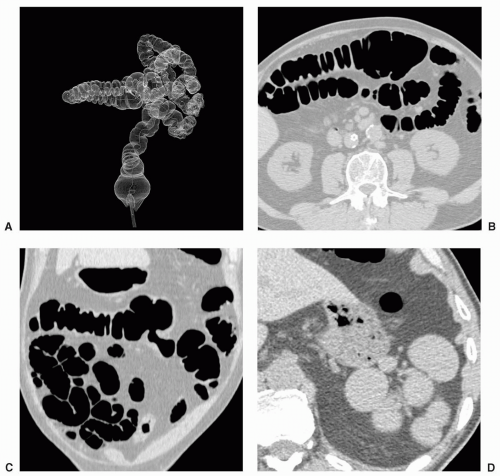

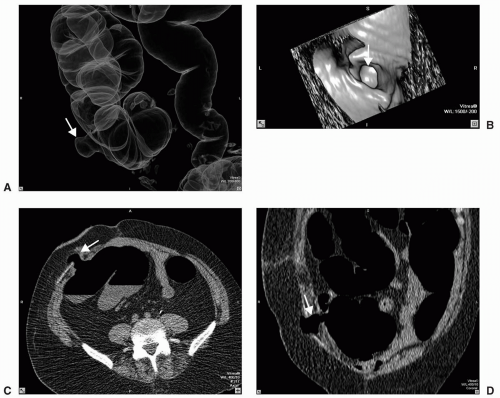

However, if malrotation occurs without clinical consequence, patients may present for CTC because of failed colonoscopy (see Figure 6.19). Findings that suggest malrotation are failure of the duodenum to cross midline to the left, vertical, or reversed orientation of the superior mesenteric vessels, and unusual position of the cecum and large bowel, or small bowel.16,18

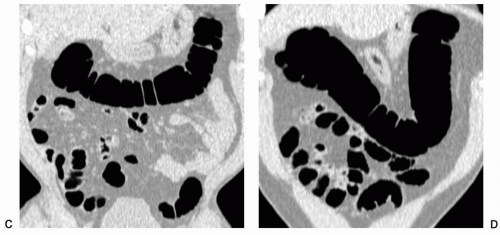

epigastric vessels (see Figure 6.21). Direct inguinal hernias occur through a weakened area of the transversalis fascia within an area referred to as Hesselbach’s triangle. The sac of a direct hernia is typically located medial to the inferior epigastric vessels. In a study by Sosna et al. four of seven patients who developed colonic perforation at CTC had left inguinal hernias that contained sigmoid colon.19 It was postulated that incarceration of the sigmoid occurred at the hernia site which was likely caused by the insufflation of air. Practice patterns were changed so that in patients with known inguinal hernia special attention was given to the inguinal region during the insufflation process and if there was increase in size of the hernia sac, air insufflation was halted. Patients with less common hernias that may involve the colon, such as Spigelian hernias (anterior abdominal wall along lateral margin of the rectus abdominus muscle), internal hernias, or hernias occurring as a result of trauma or other surgery, may present for CTC due to incomplete colonoscopy or may be detected incidentally on CTC (see Figure 6.22).

CTC has not been advocated for patients with a colostomy following APR. In a study by Burling et al. perforation of a rectal stump occurred in a patient who underwent CTC inadvertently because adequate surgical history was not communicated or elicited.21 Perforation occurred at the suture line at the apex of the rectal stump (patient presumably had prior LAR). This emphasizes the importance of obtaining a complete surgical history before performing CTC.

center of the cecum to the ICV. Any degree of rotation of this line was interpreted as axial mobility. Rotation that could impact the diagnosis was found to occur in 9/21 (43%) cases with an average rotation of 78.9 +/−27.4 degrees. In the 12 cases that did not pose a diagnostic dilemma, the average rotation was still 22.5+/−12 degrees. In addition, the main axis of rotation was varied, occurring predominantly in coronal (6 cases), sagittal (4 cases), or axial (11 cases) planes. It was concluded that rotation of the colon occurs frequently, is geometrically complex, and occurs in several planes. Multiplanar reformatted views are helpful when solid stool is suspected in the cecum to assess for rotation.

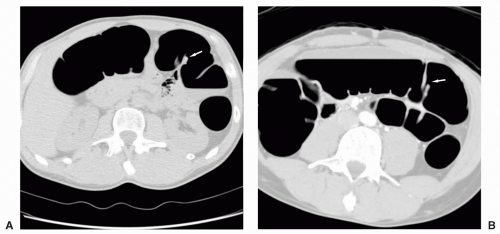

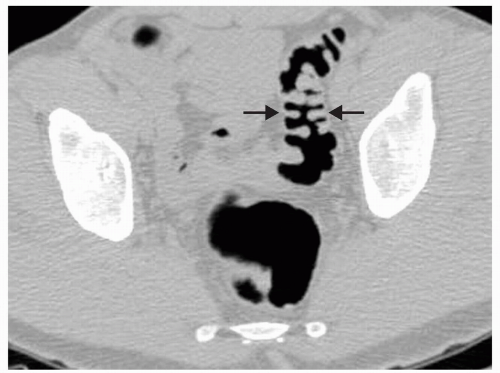

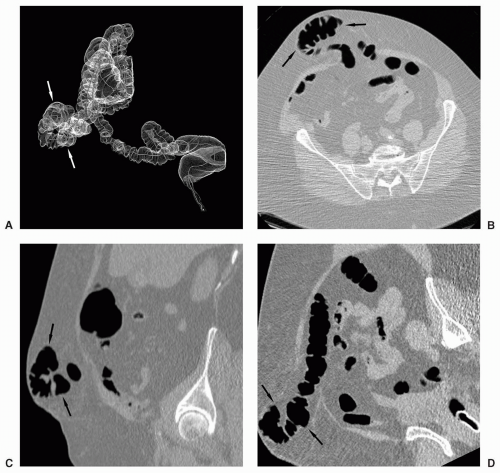

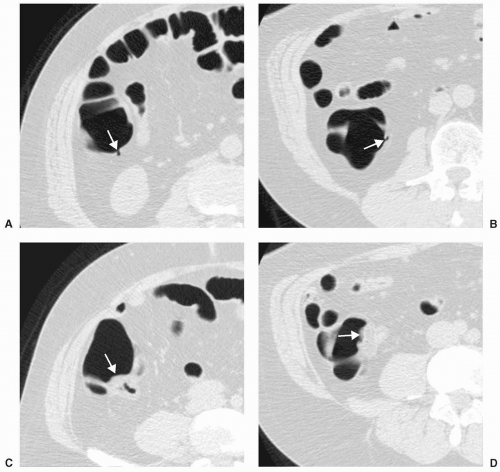

FIGURE 6.27 Mobile Sigmoid with Polyp: Supine axial view (A) shows a polyp along the posterior wall of the distal sigmoid colon. The stalk of this pedunculated polyp is seen on the prone view (B)

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|