Interpretation: Polyps and Cancer

Gregory M. Galdino

Judy Yee

COLORECTAL POLYPS

The goal of computed tomographic colonography (CTC) is to identify the precursor lesion of colorectal carcinoma, which is the adenomatous polyp. The development of colonic malignancy through the adenoma-carcinoma sequence is commonly accepted and accounts for the vast majority of colonic adenocarcinomas.1, 2, 3 and 4 Genetic mutations cause small adenomas to progress to large adenomas, which develop into noninvasive carcinoma and then into invasive carcinoma. Colorectal carcinoma is ideally suited for screening because there is a large window of opportunity to detect the precursor adenoma and to remove it before it becomes malignant. The relatively slow growth of adenomatous polyps is the basis for the relatively long intervals between colon screening examinations compared with other screening tests, such as mammography. It is estimated that the progression from adenoma to carcinoma takes approximately 5 to 10 years with 2 to 3 years for an adenoma <5 mm to progress to 1 cm, and another 2 to 5 years to then progress to carcinoma.4, 5 and 6 Some colon carcinomas have also been described as relatively slow-growing, requiring a 1-mm tumor approximately 6 to 8 years to reach 6 cm.7,8 The prevalence of polyps in the adult population is high, occurring in 50% of autopsy cases and in approximately 40% of subjects on colonoscopy surveys. Of these polyps, 80% to 90% are adenomatous or hyperplastic polyps and the overwhelming majority of these (75%) are adenomas.5 Half the number of patients with one adenoma identified are found to have a second adenoma.7

The incidence of degeneration of adenomatous polyps to malignancy is directly related to degree of dysplasia, villous histology, and polyp size. Polyps >1 cm demonstrate a significant increase in risk of malignancy.5,7 Ten percent of adenomatous polyps 1 to 2 cm in size harbor malignancy, which increases to 20% to 46% for polyps >2 cm.7 Patients with multiple adenomas and adenomas containing villous components have an even higher risk of malignancy.5 It is therefore important to recognize the characteristics of polyps and identify polyps >1 cm on CTC.

The term polyp is derived from the Greek word (polypous) meaning “many-footed.” However, polyp refers broadly to any lesion that extends above the colonic surface and protrudes into the colonic lumen.5,7,9 The term polyp is typically used for those lesions measuring up to 4 cm in size, whereas lesions >4 cm are termed masses or tumors.7 The etiology of the protrusion may result from abnormal overgrowth of the epithelial colonic mucosa or submucosal growth. Polyps may be classified according to histology, size, and morphology.

Histology

Histologically, polyps may be broadly classified into epithelial or subepithelial origins, each with neoplastic and non-neoplastic types (see Table 5.1). Neoplastic lesions may then be further subdivided into benign and malignant disease. Benign and non-neoplastic lesions of subepithelial origin can mimic true polyps or malignancies. There is currently no reliable way to differentiate between various histologic types of polyps based on their appearance on colonoscopy and CTC.

There are four main types of epithelial polyps: adenomatous, hyperplastic, inflammatory, and hamartomatous.5 Adenomatous polyps are considered benign neoplastic lesions whereas the other types are classified as non-neoplastic polyps. Adenomatous polyps display abnormal glandular architecture (dysplasia), and therefore, have malignant potential. However, only a very small percentage (3%) of adenomas will progress to malignancy.4,10 Dysplasia, or the degree of abnormality to the glandular architecture, is classified as mild, moderate, severe, or high grade. Severe and high-grade dysplasia are generally accepted histologically as carcinoma in situ.

Adenomatous polyps are divided into three histologic subtypes based on their glandular architecture: tubular, tubulovillous, and villous. Tubular adenomas contain a complex branching architecture of the glandular tissue and are the most common type. They represent approximately 85% of all adenomatous polyps and are typically smaller, measuring <10 mm.7 Tubulovillous adenomas contain both tubular and villous glandular

architecture and clinically behave according to the majority component, having a higher risk of malignant degeneration when more villous components are present. Tubulovillous adenomas account for approximately 10% of all adenomatous polyps and are often larger than tubular adenomas measuring >10 mm. Villous adenomas contain short, straight glands extending to the muscularis mucosa and are associated with a 10-times greater incidence of malignancy than tubular adenomas.7 Approximately 40% of villous adenomas will harbor infiltrating carcinoma, usually at the base of the lesion.11 Biopsies of these lesions may not be reliable and all villous adenomas should be removed. Villous adenomas are uncommon and constitute approximately 5% of all adenomas. They occur with increasing frequency in older individuals and are often larger in size, with approximately 75% measuring >2 cm.5,7,11 Common locations for villous adenomas are the rectum and cecum.7 They will often display a corrugated appearance with an irregular nodular surface because of multiple villous fronds. Villous adenomas may cause a profuse watery diarrhea, resulting in severe potassium deficiency causing muscle weakness. Many polyps contain mixed histology. Tubular adenomas may contain up to 25% villous tissue, tubulovillous adenomas contain 25% to 75% villous tissue, and villous adenomas are composed of 75% to 100% villous tissue.12 The concept of the “advanced adenoma” has developed and includes adenomatous polyps that are ≥10 mm, contains any villous component, high-grade dysplasia, or invasive carcinoma.13 Familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome (FAPS) is a genetic disorder that includes familial polyposis coli and Gardner syndrome. Innumerable, small (≤5 mm) tubular and tubulovillous adenomas typically develop in the colon although villous adenomas can also occur. Medium-sized polyps may also be seen, but if there is a large polyp there should be high suspicion for malignancy. Colorectal adenocarcinoma will develop in almost all patients and therefore prophylactic total colectomy is usually performed.

architecture and clinically behave according to the majority component, having a higher risk of malignant degeneration when more villous components are present. Tubulovillous adenomas account for approximately 10% of all adenomatous polyps and are often larger than tubular adenomas measuring >10 mm. Villous adenomas contain short, straight glands extending to the muscularis mucosa and are associated with a 10-times greater incidence of malignancy than tubular adenomas.7 Approximately 40% of villous adenomas will harbor infiltrating carcinoma, usually at the base of the lesion.11 Biopsies of these lesions may not be reliable and all villous adenomas should be removed. Villous adenomas are uncommon and constitute approximately 5% of all adenomas. They occur with increasing frequency in older individuals and are often larger in size, with approximately 75% measuring >2 cm.5,7,11 Common locations for villous adenomas are the rectum and cecum.7 They will often display a corrugated appearance with an irregular nodular surface because of multiple villous fronds. Villous adenomas may cause a profuse watery diarrhea, resulting in severe potassium deficiency causing muscle weakness. Many polyps contain mixed histology. Tubular adenomas may contain up to 25% villous tissue, tubulovillous adenomas contain 25% to 75% villous tissue, and villous adenomas are composed of 75% to 100% villous tissue.12 The concept of the “advanced adenoma” has developed and includes adenomatous polyps that are ≥10 mm, contains any villous component, high-grade dysplasia, or invasive carcinoma.13 Familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome (FAPS) is a genetic disorder that includes familial polyposis coli and Gardner syndrome. Innumerable, small (≤5 mm) tubular and tubulovillous adenomas typically develop in the colon although villous adenomas can also occur. Medium-sized polyps may also be seen, but if there is a large polyp there should be high suspicion for malignancy. Colorectal adenocarcinoma will develop in almost all patients and therefore prophylactic total colectomy is usually performed.

TABLE 5.1 Classification of Polypoid Lesions of the Colon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hyperplastic polyps are the most common nonneoplastic type of colorectal polyp and have no malignant potential. They represent a focal proliferation of the colonic mucosal epithelium, typically occurring adjacent to or on a haustral fold.11 Hyperplastic polyps are typically small (<5 mm) and sessile and most commonly occur in the rectosigmoid colon. Most hyperplastic polyps are located in the left colon with three quarters distal to the splenic flexure and half occurring in the rectosigmoid region.11,14 Up to 50% of polyps <5 mm are hyperplastic.15 Colonoscopy surveillance recommendations by the US Multisociety Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American Cancer Society states specifically that patients with small rectal hyperplastic polyps should be considered to have normal colonoscopies and therefore the interval before the subsequent colonoscopy should be 10 years.16

Hyperplastic polyps often have a soft consistency and may become effaced or flattened in a well-distended colon during CTC, causing them to be missed more frequently than adenomas.17,18 Nonadenomatous polyps accounted for 57.7% of all colorectal polyps and 39.9% of polyps ≥6 mm in a study evaluating CTC performed in a screening population.19 Hyperplastic polyps represented the majority (75.4%) of nonadenomatous lesions ≥6 mm. The sensitivity for detection of hyperplastic polyps ranged between 72.2% to 76.2% at 6-, 8-, and 10-mm thresholds, whereas the sensitivity for adenomatous polyp detection was higher for all three thresholds at 85.7%, 92.6%, and 92.2% respectively. Hyperplastic lesions >10 mm were often found to have an elongated or flattened appearance, making them less detectable on CTC. This may have clinical significance because more recently there has been described the hyperplastic polyposis syndrome, where patients with multiple large (≥10 mm) hyperplastic polyps have been found to have increased risk for adenomas and colorectal cancer.16,20

Hamartomatous (juvenile) polyps occur sporadically in children younger than 10 years.5 They affect 1% to 2% of all children and carry no significant malignant potential when solitary. These polyps are typically pedunculated and located predominantly in the rectosigmoid. In approximately one third of patients, these polyps are inherited and multiple occurring as part of the juvenile polyposis syndrome. In this situation, the hamartomatous polyps may contain foci of dysplasia and there is a 10% risk

for developing colon cancer.21 Colonic hamartomas may rarely be found in adults. A retrospective study of more than 12,000 patients found a prevalence of 0.15% in an adult population.22 Colonic hamartomas were more common in men. Three fourths of the polyps were >10 mm and 89% were pedunculated. Two thirds were located in the rectosigmoid. Endoscopic characteristics of hamartomatous polyps are indistinguishable from adenomatous polyps. Hamartomatous polyps may also occur in adults as part of a polyposis syndrome such as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, Cowden syndrome (multiple hamartoma syndrome), and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome.

for developing colon cancer.21 Colonic hamartomas may rarely be found in adults. A retrospective study of more than 12,000 patients found a prevalence of 0.15% in an adult population.22 Colonic hamartomas were more common in men. Three fourths of the polyps were >10 mm and 89% were pedunculated. Two thirds were located in the rectosigmoid. Endoscopic characteristics of hamartomatous polyps are indistinguishable from adenomatous polyps. Hamartomatous polyps may also occur in adults as part of a polyposis syndrome such as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, Cowden syndrome (multiple hamartoma syndrome), and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome.

Inflammatory polyps represent focal regions of granulomatous tissue protruding into the lumen and appears as a single small lesion in adults. Rarely inflammatory polyps are large and can mimic adenomas or carcinomas. Inflammatory pseudopolyps occur in patients with acute inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) and represent residual islands of inflamed colonic tissue in a region of denuded mucosa.5 Inflammatory pseudopolyps are benign but may be confused with adenomatous polyps. Colonic perforation has been reported in patients with acute inflammatory bowel disease who undergo CTC.23,24 CTC is not typically performed in the setting of acute inflammatory bowel disease. Caution is advised to avoid perforating the bowel if it is necessary to perform CTC in this setting.

One percent of polyps are serrated adenomas (mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps), which demonstrate hyperplastic polyp architecture with adenomatous cytology. Histologically, these lesions have a serrated, crypt architecture in association with surface epithelial dysplasia. In a study of 919 individuals there was a 1 % prevalence of serrated adenomas with an average size of 5.8 mm.25 High-grade dysplasia occurs in up to 40% of serrated adenomas and these lesions are considered to have increased malignant potential.5,16,26,27

Size

Polyp size is an important measurement obtained on CTC. The largest diameter of a polyp (excluding the stalk of a pedunculated polyp) is often used as a surrogate parameter for clinical importance (likelihood of harboring malignancy) upon which patient management decisions are based. The chance of malignancy in a polyp is related to polyp size and <1% of polyps <10 mm will be malignant (see Table 1.3).15,28 Therefore, traditionally polyps measuring ≥10 mm have been considered to be clinically significant. Polyps may be classified as small (≤5 mm), medium (6 to 9 mm) or large (≥10 mm). The terms used for ranges of polyp sizes may vary with alternative classification of polyps as diminutive (≥5 mm), small (6 to 9 mm) or large (≥10 mm).29

Small polyps have been found to be evenly distributed throughout the colon. A higher prevalence of small adenomatous polyps has been identified proximally in the right colon with more non-neoplastic or hyperplastic polyps found in the rectum.30 Although studies have found that the incidence of malignancy in small polyps is low, some still recommend removal of all polyps including those ≤5 mm.30,31 Others have evaluated the multiple features of small polyps including the low risk of malignancy and suggest a focus on detection of those lesions that have more significant carcinoma risk.32,33 The American College of Radiology Practice Guidelines for the performance of CTC in adults suggests that small polyps ≤5 mm do not need to be reported because these lesions are commonly non-neoplastic.34 The risk of malignancy in this size range is very low at <0.01%. Additionally, many of these small polyps prove to be false positives on CTC or even if they are true lesions colonoscopy may miss 25% of them.

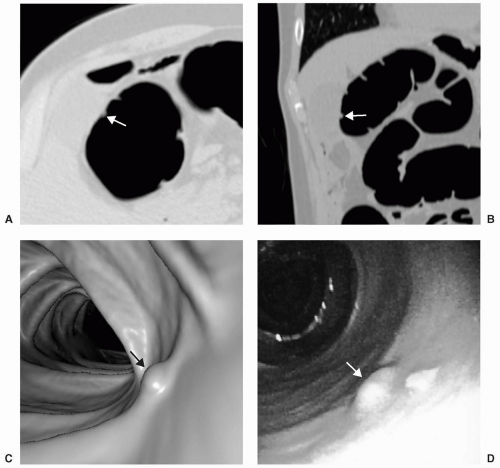

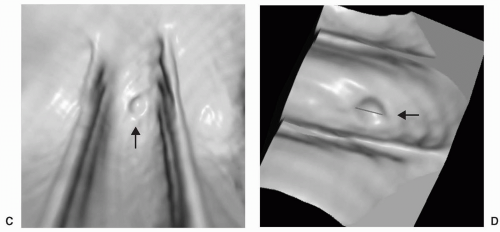

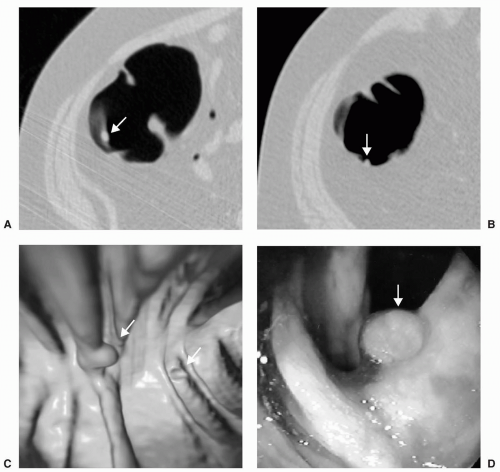

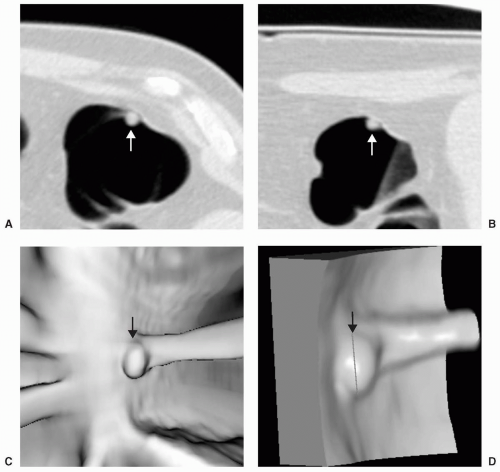

Small or diminutive polyps (≤5 mm) are rarely pedunculated and almost always sessile. Most of these small lesions are hyperplastic polyps. Small polyps tend to be smooth and round or ovoid in appearance rather than lobular (see Figs. 5.1 and 5.2). Medium-sized polyps (6-9 mm) are also more often sessile than pedunculated (see Figs. 5.3 and 5.4). They have an overall <1% chance of harboring malignancy. Polyps of this size category have approximately a 50% chance of being adenomatous. If adenomatous, there is a 5% to 10% incidence of malignancy within 10 years.28 Controversy exists as to whether medium-sized polyps should be the target lesions for colorectal cancer screening rather than large polyps measuring ≥10 mm. Detection sensitivity for medium-sized polyps is higher than for small polyps and lower than for large polyps on both CTC and optical colonoscopy. Computer-aided detection of medium-sized polyps may prove to be valuable in increasing the sensitivity for these lesions.

Large polyps measuring ≥10 mm are more easily detected on CTC (see Figs. 5.5 and 5.6). Approximately 40% of large polyps have been found to have an irregular surface on CTC, which may be due to intrinsic mucosal irregularity or adherent stool (see Fig. 5.7).35 Most large polyps will be adenomatous (>80%).28 Although hyperplastic polyps are typically small (≤5 mm), occasionally they may be large (≥10 mm) and flat (see Fig. 5.8). Hyperplastic polyps are indistinguishable from adenomas on CTC and colonoscopy.

The prevalence of adenomatous polyps measuring 6 mm, 8 mm, and >10 mm was 13.6%, 6.7%, and 3.9% respectively as determined in a study evaluating CTC in a large asymptomatic screening patient population. Therefore, the likelihood of an average-risk patient having a large clinically significant polyp on screening CTC is low.36 In this same study, it was estimated that approximately 15% of screening patients who undergo screening CTC would be referred to colonoscopy at a threshold of 8 mm, which decreases to 7.5% at a threshold of 10 mm. The higher referral rate relative to prevalence rate is likely due to the detection of false positive findings on CTC.

Morphology

Polypoid lesions in the colon should be evaluated for mobility, homogeneity (internal attenuation), and morphology to distinguish residual stool and other pitfalls

from polyps. Polyps typically occur in the same location within the colonic segment (nonmobile) on opposing views, demonstrate homogenous soft tissue attenuation, and are smooth, round, lobulated, or ovoid without geometric borders or sharp angles. However, polyps may be mobile, especially when pedunculated and upon a long stalk or may appear to be mobile if located within colonic segments that are mobile (sigmoid, transverse: cecum).37 Morphologically, polyps can be classified as sessile, pedunculated, and flat lesions (see Fig. 5.9). Some lesions have also been described as “subpedunculated” when they have a mixed morphology between sessile and pedunculated.

from polyps. Polyps typically occur in the same location within the colonic segment (nonmobile) on opposing views, demonstrate homogenous soft tissue attenuation, and are smooth, round, lobulated, or ovoid without geometric borders or sharp angles. However, polyps may be mobile, especially when pedunculated and upon a long stalk or may appear to be mobile if located within colonic segments that are mobile (sigmoid, transverse: cecum).37 Morphologically, polyps can be classified as sessile, pedunculated, and flat lesions (see Fig. 5.9). Some lesions have also been described as “subpedunculated” when they have a mixed morphology between sessile and pedunculated.

FIGURE 5.5 Large Sessile Polyp and the Importance of 3D Measurement. Axial supine (A) and prone (B)

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|