Intervention

Effect estimates

Water sanitation and hygiene

48, 17, and 36 % risk reductions for diarrhea with hand washing with soap, improved water quality and excreta disposal, respectively

Breastfeeding education and impacts on breastfeeding patterns

EBF rates increase by 43 % at 1 day, 30 % till 1 month, and 79 % from 1 to 6 months

Rates of no breastfeeding decrease by 32 % at 1 day, 30 % till 1 month, and 18 % from 1 to 6 months

Preventive zinc supplementation

18 % reduction in diarrhea-related mortality

Preventive vitamin A supplementation

All-cause mortality reduced by 24 % (RR: 0.76, 95 % CI: 0.69–0.83), diarrhea related mortality by 28 % (RR: 0.72, 95 % CI: 0.57–0.91), incidence of diarrhea reduced by 15 % (RR: 0.85, 95 % CI: 0.82–0.87)

Vaccines for rotavirus

74 % reduction in very severe rotavirus infection

47 % reduction in rotavirus hospitalization

Vaccines for cholera

52 % effective against cholera infection

ORS

69 % reduction in diarrhea specific mortality

Dietary management of diarrhea

Lactose free diets reduce the duration of diarrhea treatment failure rates by 47 %

Therapeutic zinc supplementation

66 % reduction in diarrhea-specific mortality

23 % reduction in subsequent diarrhea hospitalization

19 % reduction in subsequent diarrhea

Antibiotics for cholera

63 % reduction in clinical failure rates

75 % reduction in bacteriological failure rates

Antibiotics for Shigella

82 % reduction in clinical failure

96 % reduction in bacteriological failure rates

Antibiotics for cryptosporidiosis

52 % reduction in clinical failure rates

38 % reduction in parasitological failure rates

Community based intervention platforms for prevention

160 % increase in the use of ORS

80 % increase in the use of zinc in diarrhea

76 % decline in the use of antibiotics for diarrhea

Community case management

63 % reduction in diarrhea related mortality

Financial support schemes

Conditional transfer programs: 14 % increase in preventive health care use, 22 % increase in the percentage of newborns receiving colostrum and 16 % increase the coverage of vitamin A supplementation

Rapid Resuscitation, Antibiotic Therapy, and Stabilization

Most children with persistent diarrhea and associated malnutrition are not severely dehydrated and oral rehydration may be adequate. Indeed, routine use of intravenous fluids in severe acute malnutrition should be avoided; acute severe dehydration and associated vomiting may require brief periods of intravenous rehydration with Ringer’s lactate. Acute electrolyte imbalance such as hypokalemia and severe acidosis may require correction. More importantly, associated systemic infections (bacteremia, pneumonia, and urinary tract infection) are well-recognized complications of severe acute malnutrition in children with persistent diarrhea and a frequent cause of early mortality. Almost 30–50 % of malnourished children with persistent diarrhea may have an associated systemic infection requiring resuscitation and antimicrobial therapy [33, 34]. In severely ill children requiring hospitalization, it may be best to cover with parenteral antibiotics at admission (usually ampicillin and gentamicin) while awaiting blood and other culture results. It should be emphasized that there is little role for oral antibiotics in persistent diarrhea as in most cases the original bacterial infection triggering the prolonged diarrhea has disappeared by the time the child presents. Possible exceptions are appropriate treatment for dysentery [8] and adjunctive therapy for cryptosporidiosis in children with HIV and persistent diarrhea [35].

Oral Rehydration Therapy

It is over 40 years since the efficacy of oral rehydration therapy was clearly demonstrated, following discovery of glucose-stimulated sodium uptake by intestinal villus cells [36]. This is the preferred mode of rehydration and replacement of ongoing losses. The net effect is expansion of the intravascular compartment and rehydration, usually sufficient for all but the most severely dehydrated patients who require initial intravenous fluids [37]. Data from several clinical trials supported a change in the composition of the WHO ORS to a solution of lowered osmolality. While in general the standard WHO oral rehydration solution is adequate, recent evidence indicates that hypo-osmolar rehydration fluids [38] as well as cereal-based oral rehydration fluids may be advantageous in malnourished children. A number of modifications have been proposed, for example cereal (rice)-based ORT, addition of certain amino acids (glycine, alanine, or glutamine) to further increase sodium absorption and/or hasten intestinal repair, or supplementation with zinc, but none have been shown to be consistently superior to low-osmolality ORS [39, 40].

Enteral Feeding

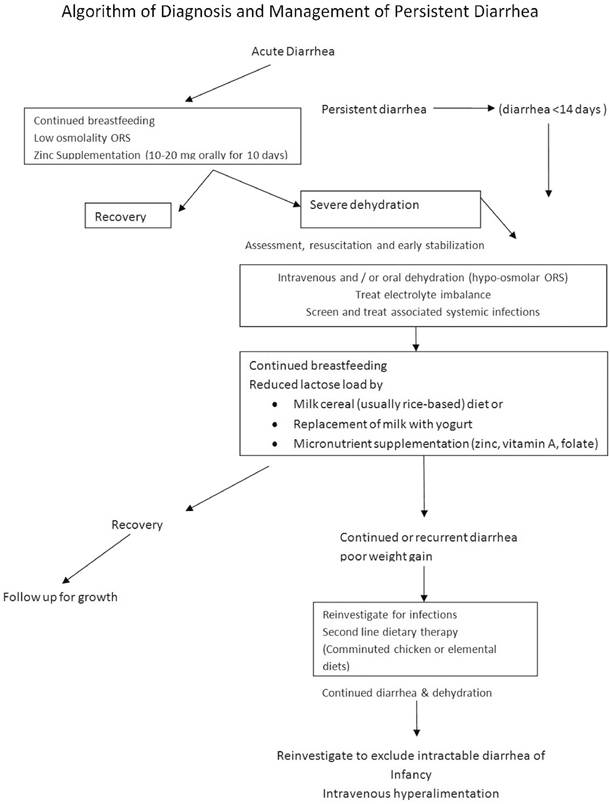

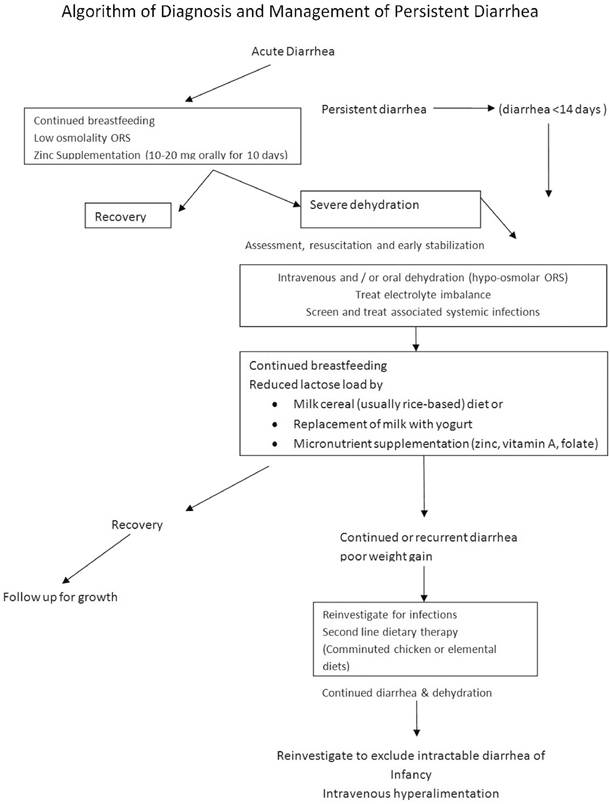

Nutritional rehabilitation can break the vicious cycle of chronic diarrhea and malnutrition and is considered the cornerstone of treatment. It is exceedingly rare to find persistent diarrhea in exclusively breast-fed infants, and with the exception of situations where persistent diarrhea accompanies perinatally acquired HIV infection, breastfeeding must be continued. Although children with persistent diarrhea may not be lactose intolerant, administration of a lactose load exceeding 5 g/kg/day may be associated with higher purging rates and treatment failure. Alternative strategies for reducing the lactose load while feeding malnourished children who have prolonged diarrhea include addition of milk to cereals and replacement of milk with fermented milk products such as yogurt. Mattos et al. [41] claimed that yogurt-based diet is recommended as the first choice for the nutritional management of a mild to moderate persistent diarrhea. A cheap and an easily available yogurt-based diet can be used in mild chronic diarrhea illness of uncomplicated and without enteropathy. Bhutta et al. [18] suggested algorithm for the diagnosis and management of persistent diarrhea (Fig. 17.1). Elimination diet is considered when allergic enteropathy is induced by a cow’s milk protein or soy protein [42]. Rarely, when dietary intolerance precludes the administration of cow’s milk-based formulations or milk it may be necessary to administer specialized milk-free diets such as a comminuted or blended chicken-based diet or an elemental formulation. Although effective in some settings, the latter are unaffordable in most developing countries. In addition to rice-lentil formulations, the addition of green banana or pectin to the diet has also been shown to be effective in the treatment of persistent diarrhea [43, 44]. Among children in low- and middle-income countries, where the dual burden of diarrhea and malnutrition is greatest and where access to proprietary formulas and specialized ingredients is limited, the use of locally available age-appropriate foods should be promoted for the majority of diarrhea cases. Nutritionally complete diets comprising locally available ingredients can be used at least as effectively as commercial preparations or specialized ingredients. The usual energy density of any diet used for the therapy of persistent diarrhea should be around 1 kcal/g, aiming to provide an energy intake of a minimum 100 kcal/kg/day, and a protein intake of between 2 and 3 g/kg/day. In selected circumstances, when adequate intake of energy-dense food is problematic, the addition of amylase to the diet through germination techniques may also be helpful. Recent WHO guidelines recommends that children with severe acute malnutrition who present with either acute or persistent diarrhea , can be given ready-to-use therapeutic food in the same way as children without diarrhea, whether they are being managed as inpatients or outpatients. And these children with severe acute malnutrition should also be provided with about 5000 IU vitamin A daily, either as an integral part of therapeutic foods or as part of a multi-micronutrient formulation [45].

Fig. 17.1

Algorithm of diagnosis and management of persistent diarrhea

Micronutrient Supplementation

It is now widely recognized that most malnourished children with persistent diarrhea have associated deficiencies of micronutrients including zinc, iron, and vitamin A . This may be a consequence of poor intake and continued enteral losses and requires replenishment during therapy [46]. While the evidence supporting zinc administration in children with persistent diarrhea is persuasive, it is likely that these children have multiple micronutrient deficiencies. Concomitant vitamin A administration to children with persistent diarrhea has been shown to improve outcome [47, 48] especially in HIV endemic areas [49]. It is therefore important to ensure that all children with persistent diarrhea and malnutrition receive an initial dose of 100,000 units Vitamin A and a daily intake of at least 3–5 mg/kg/day of elemental zinc. While the association of significant anemia with persistent diarrhea is well recognized, iron replacement therapy is best initiated only after recovery from diarrhea has started and the diet is well tolerated .

Improved Case Management of Diarrhea

Improved management of diarrhea through prompt identification and appropriate therapy significantly reduces diarrhea duration, its nutritional penalty, and risk of death in childhood. Improved management of acute diarrhea is a key factor in reducing the burden of prolonged episodes and persistent diarrhea. The WHO/UNICEF recommendations to use low-osmolality ORS and zinc supplementation for the management of diarrhea, coupled with selective and appropriate use of antibiotics, have the potential to reduce the number of diarrheal deaths among children through community case management and integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI). Community-based interventions to diagnose and treat childhood diarrhea through community health workers leads to a significant rise in care-seeking behaviors for diarrhea and are associated with significantly increased use of ORS and zinc at household level as well as reduction in the unnecessary use of antibiotics for diarrhea [50].

Other Potential Modalities

The factors associated with persistent diarrhea are small intestinal mucosa injury, persisting infective colonization and bacterial particles and toxins that are translocated into the host cell and the downregulated host immune system . These circumstances alter interrelation between the normal flora and the host, which can worsen prolonged inflammation. The rationale for using probiotics in treatment of persistent diarrhea lies in their ability to survive and reproduce in the host’s gut and in their proven role in treatment of acute diarrhea. Recent evidence suggests modest effect of probiotics [51]. Because of probiotics known immunomodulatory effect and very significant mortality and morbidity rate from persistent diarrhea in developing countries, it is imperative to highlight the necessity for well-designed studies to define the role of probiotics in persistent diarrhea .

Follow-Up and Nutritional Rehabilitation in Community Settings

Given the high rates of relapse in most children with persistent diarrhea, it is important to address the underlying risk factors and institute preventive measures. These include appropriate feeding (breastfeeding, complementary feeding) and close attention to environmental hygiene and sanitation. This poses a considerable challenge in communities deprived of basic necessities such as clean water and sewage disposal.

In addition to the preventive aspects, the challenge in most settings is to develop and sustain a form of dietary therapy using inexpensive, home-available, and culturally acceptable ingredients which can be used to manage children with persistent diarrhea . Given that the majority of cases of persistent diarrhea occur in the community and that parents are frequently hesitant to seek institutional help, there is a need to develop and implement inexpensive and practical home-based therapeutic measures [18] and evidence indicates that it may be entirely feasible to do so in community settings [52, 53].

Conclusion

There is a significant burden of persistent diarrhea in children and it also contributes to childhood malnutrition and mortality. Most of the knowledge and tools needed to prevent diarrhea-associated mortality in developing countries and especially persistent diarrhea are available. These require concerted and sustained implementation in public health programs. Given the emerging evidence of the long-term impact of childhood diarrhea on developmental outcomes [54], it is imperative that due emphasis is placed on prompt recognition and appropriate management of persistent diarrhea.

References

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree