Fig. 44.1

Main elements of the ERAS protocol (Reprinted from Fearon et al. [59]; with permission from Elsevier)

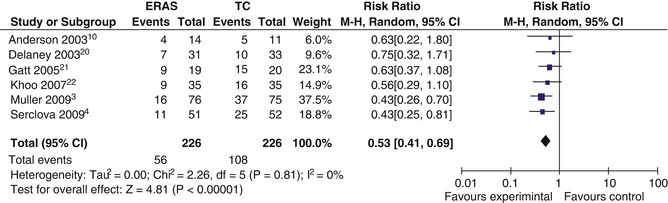

Fig. 44.2

Complications within an eras program. Forest plot of comparison: ERAS (experimental group), Traditional Care (Control) (Reprinted from Varadhan et al. [3]; with permission from Elsevier)

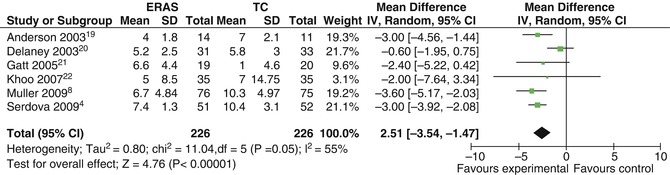

Fig. 44.3

Length of hospital stay (days) within an eras program. Forest plot of comparison: ERAS (experimental group), Traditional Care (Control) (Reprinted from Varadhan et al. [3]; with permission from Elsevier)

Perioperative care consists of pre-, intra- and postoperative interventions. This chapter will subdivide the interventions based on the chronological order in the patient’s journey.

Throughout this chapter the information is based on published evidence which has been summarized in Table 44.1 [5, 6].

Table 44.1

Guidelines for perioperative care in elective rectal/pelvic surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) society recommendations

Item | Recommendation | Evidence level | Recommendation guide |

|---|---|---|---|

Preoperative information, education and counseling | Patients should routinely receive dedicated preoperative counseling | Low | Strong |

Preoperative optimization | Preoperative optimization of medical conditions (e.g., anemia), cessation of smoking and alcohol intake 4 weeks before rectal surgery is recommended. Increasing exercise preoperatively may be of benefit. Preoperative specialized nutritional support should be considered for malnourished patients | Medical optimization: moderate | Medical optimization: strong |

Pre-habilitation: very low | Pre-habilitation: no | ||

Cessation of smoking: Strong | |||

Cessation of excess consumption of alcohol: strong | |||

Cessation of smoking: moderate | |||

Cessation of excess consumption of alcohol: low | |||

Preoperative bowel preparation | In general, MBP should not be used in pelvic surgery. However, when a diverting ileostomy is planned, MBP may be necessary (although this needs to be studied further) | Anterior resection: (no MBP) high | Anterior resection: strong |

Total mesorectal excision (TME) with diverting stoma: (use MBP) low | TME with diverting stoma: weak | ||

Preoperative fasting | Intake of clear fluids up to 2 h and solids up to 6 h prior to induction of anesthesia | Moderate | Strong |

Preoperative treatment with carbohydrates | Preoperative oral carbohydrate loading should be administered to all non-diabetic patients | Reduced postop insulin resistance: moderate | Strong |

Improved clinical outcomes: low | |||

Preanesthetic medication | No advantages in using long-acting benzodiazepines | Moderate | Strong |

Short-acting benzodiazepines can be used in young patients before potentially painful interventions (insertion of spinal or epidural, arterial catheter), but they should not be used in the elderly (age >60 years) | |||

Prophylaxis against thromboembolism | Patients should wear well-fitting compression stockings, and receive pharmacological prophylaxis with LMWH. Extended prophylaxis for 28 days should be considered in patients with colorectal cancer or other patients with increased risk of VTE | ||

High | Strong | ||

Antimicrobial prophylaxis | Patients should receive antimicrobial prophylaxis before skin incision in a single dose. Repeated doses may be necessary depending on the half-life of drug and duration of surgery | High | Strong |

Skin preparation | A recent RCT has shown that skin preparation with a scrub of chlorhexidine-alcohol is superior to povidone-iodine in preventing surgical-site infections | Moderate | For skin preparation in general: strong |

Specific choice of preparation: weak | |||

Standard anesthetic protocol | To attenuate the surgical stress response, intraoperative maintenance of adequate hemodynamic control, central and peripheral oxygenation, muscle relaxation, depth of anesthesia, and appropriate analgesia is strongly recommended | Epidural: moderate | Epidural: strong |

IV lidocaine: low | IV lidocaine: weak | ||

Remifentanil: low | Remifentanil: strong | ||

High oxygen concentration: high | High oxygen concentration: strong | ||

PONV | Prevention of PONV should be included as standard in ERAS protocols. More specifically, a multimodal approach to PONV prophylaxis should be adopted in all patients with two or more risk factors undergoing major colorectal surgery. If PONV is present, treatment should be via a multimodal approach | High-risk patients: high | Strong |

In all patients: low | |||

Laparoscopic resection of benign disease | With proven safety and at least equivocal disease-specific outcomes, laparoscopic proctectomy and proctocolectomy for benign disease can be carried out by an experienced surgeon within an ERAS protocol with the goals of reduced perioperative stress (manifested by decreased postoperative ileus), decreased LOSH, and fewer overall complications | Low | Strong |

Laparoscopic resection of rectal cancer | Laparoscopic resection of rectal cancer is currently not generally recommended outside of a trial setting (or specialized center with ongoing audit) until equivalent oncologic outcomes are proven | Moderate | Strong |

Nasogastric intubation | Postoperative nasogastric tubes should not be used routinely | High | Strong |

Preventing intraoperative hypothermia | Patients undergoing rectal surgery need to have their body temperature monitored during and after surgery. Attempts should be made to avoid hypothermia because it increases the risk of perioperative complications | High | Strong |

Perioperative fluid management | Fluid balance should be optimized by targeting cardiac output and avoiding overhydration. Judicious use of vasopressors is recommended with arterial hypotension. Targeted fluid therapy using the oesophageal Doppler system is recommended | Moderate | Strong |

Drainage of peritoneal cavity | Pelvic drains should not be used routinely | Low | Weak |

Transurethral catheter | After pelvic surgery with a low estimated risk of postoperative urinary retention, the transurethral bladder catheter may be safely removed on postoperative day 1, even if epidural analgesia is used | Low | Weak |

Suprapubic catheter | In patients with an increased risk of prolonged postoperative urinary retention, placement of a suprapubic catheter is recommended | Prolonged catheterization: low | Weak |

Chewing gum | A multimodal approach to optimizing gut function after rectal resection should involve chewing gum | Moderate | Strong |

Postoperative laxatives and prokinetics | A multimodal approach to optimizing gut function after rectal resection should involve oral laxatives | Low | Weak |

Postoperative analgesia | TEA is recommended for open rectal surgery for 48–72 h in view of the superior quality of pain relief compared with systemic opioids. Intravenous administration of lidocaine has also been shown to provide satisfactory analgesia, but the evidence in rectal surgery is lacking. If a laparoscopic approach is used, epidural or intravenous lidocaine, in the context of ERAS, provides adequate pain relief and no difference in the duration of LOSH and return of bowel function. Rectal pain can be of neuropathic origin, and needs to be treated with multimodal analgesic methods. There is limited evidence for the routine use of wound catheters and continuous TAP blocks in rectal surgery | Epidural for open surgery: high | Epidural for open surgery: strong |

Epidural for laparoscopy: weak | |||

Epidural for laparoscopy: low | Intravenous lidocaine: weak | ||

Intravenous lidocaine: moderate | |||

Wound infiltration and TAP blocks: weak | |||

Wound infiltration and TAP blocks: low | |||

Early oral intake | An oral ad libitum diet is recommended 4 h after rectal surgery | Moderate | Strong |

Oral nutritional supplements | In addition to normal food intake, patients should be offered ONS to maintain adequate intake of protein and energy | Low | Strong |

Postoperative glucose control | Maintenance of perioperative blood sugar levels within an expert-defined range results in better outcomes. Therefore, insulin resistance and hyperglycemia should be avoided using stress-reducing measures, or if already established by active treatment. The level of glycemia to target for intervention at the ward level remains uncertain, and is dependent upon local safety aspects | Use of stress-reducing measures: moderate | Use of stress-reducing treatments: strong |

Level of glycemia for insulin treatment: low | Insulin treatment (non- diabetics) at the ward level: weak | ||

Early mobilization | Patients should be nursed in an environment that encourages independence and mobilization. A care plan that facilitates patients being out of bed for 2 h on the day of surgery and 6 h thereafter is recommended | Low | Strong |

44.2 Pre-operative Care

Health Optimization: Prediction of Risk

Although some specialties will not undertake surgery in people with reversible risk, e.g. smoking or obesity, this is often not possible in patients coming for cancer interventions due to the short time frame. Risk should however be predicted and minimized by optimization of the preoperative health status e.g. stopping smoking [7] and excess alcohol intake [8] for at least 4 weeks prior to surgery, when time allows. We would routinely ensure that anyone with significant cardiac comorbidity undergoes examination using stress echocardiography, and if necessary, angiographic evaluation. Those people with compromised respiratory function would also have appropriate assessment of their respiratory capacity in order to ensure the anesthetist is fully informed regarding any limitation and, when possible, to improve function. Other comorbidities such as renal function should be assessed and all factors taken into consideration when planning whether to operate, what operation to perform and what risk of mortality and morbidity to state when taking consent.

In order to improve risk prediction and allow comparison between populations, the Physiological & Operative Severity Score for the enumeration of mortality and morbidity (POSSUM) was devised. It uses 12 physiological and six surgical parameters in order to calculate the risk of intervention. An adaptation for colorectal surgery, the ColoRectal POSSUM (CR-POSSUM) use only six physiological parameters and four operative measures for prediction of morbidity [9]. Their accuracy is limited but their major disadvantage is that they require intraoperative data for their calculation. The use of cardiopulmonary exercise (CPEx) testing provides a combined assessment of cardiac and respiratory fitness following exercise and will provide the team and, more importantly the patient, with an objective assessment of the risk of intervention. Swart and Carlisle [10] have used CPEx testing and risk assessment preoperatively and identified factors which independently influence subsequent year on year mortality. They showed that attending a consultant lead preoperative clinic and admission to a perioperative critical care unit reduce adverse outcomes [11]. A 6 min walking test has been well validated [12] for the prediction of risk and is a relatively straight forward assessment. That and other approaches such as comorbidity measurement and frailty testing [13] have the potential to impact on outcome by altering the approach to surgery or choice of operation, but to date have been routinely used in very few centers.

Conditioning of Expectation and Pre-assessment

Sir David Cuthbertson (1900–1989), a biochemist working in Glasgow during the 1920s, was one of the first scientists to uncover the link between the physiological (neuro-hormonal) stress response and the negative impact it can have on outcomes. We have built on that principle by providing explicit preoperative information including goal setting, which facilitates postoperative recovery, pain control and discharge [14]. A clear explanation of expectations prior to and during hospitalization facilitates adherence to the care pathway, allowing patients to feel part of and to expedite their recovery. The knowledge of targets including nutrition, mobilization and other tasks provides encouragement and positive reinforcement, leading to earlier recovery and discharge[5]. Our standard approach to this is the provision of written and oral information 1–2 weeks preoperatively by a dedicated preadmission nurse for all patients undergoing elective rectal resection. This usually takes 30—40 min and is performed with a family member or friend present in order to aid discharge planning. It will be scheduled earlier and with medical assessment when patients have certain comorbidities in order to correctly identify them, thus allowing time for optimization if possible.

Pre-operative Preparation

1.

There are few reasons now to admit patients the day before surgery as when admitted on the day of surgery they will experience decreased levels of stress and have less chance of acquiring resistant organisms.

2.

It is not advantageous to administer preoperative long acting sedatives or relaxants since they will delay postoperative recovery and mobilization [15].

3.

The use of mechanical bowel preparation in colorectal surgery has been shown to increase anastomotic leakage in randomized trials, as well as increasing dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities, especially in the elderly and renally impaired [16, 17]. The French Greccar III Multicenter Single-Blinded RT of low anterior resection for rectal cancer did however link those without mechanical bowel preparation to higher overall and infectious morbidity, but without any significant increase in anastomotic leak rate [18]. This was not proven in a multicenter RCT assessing anastomotic leakage and septic complications below the peritoneal verge [19]. This study, when examining covering ileostomies, in a subgroup analysis, found no difference when assessing complications in patients without MBP both with and without a diverting ileostomy. Platell [20] however argues that if the pelvic abscesses reported in this study plus those of Jung [21] (another large clinical trial) are included as ‘anastomotic leaks’ there is a significant benefit to those who receive MBP. Furthermore, Matthiesson [22] as well as a Cochrane study [23] (which included Matthiesson’s data) have demonstrated that total mesorectal excision (TME) without a covering stoma is associated with increased leak rates and the consequences of leakage.

For these reasons we perform a defunctioning loop stoma when performing TME. In order to avoid a column of stool between the stoma and the anastomosis which might worsen morbidity if leakage occurs, we currently still administer mechanical bowel preparation for TME surgery. We merely use a phosphate enema preoperatively in patients undergoing abdominoperineal excision (APE) of the rectum or high anterior resection (PME).

4.

Preoperative pharmacological prophylaxis is recommended to reduce symptomatic venous thromboembolism (VTE), without increasing side effects such as bleeding. Additionally, compression stockings reduce the incidence of VTE. Both in hospital prophylaxis and 4 week post operative continued prophylaxis has been associated with significantly reduced VTE, without an increase in postoperative bleeding complications or other side effects. We currently only administer heparin preoperatively and during the hospital stay due to the low incidence of VTE in our practice. Care should be taken if an epidural analgesic protocol is to be used and we administer prophylactic heparin not less than 12 h before the planned procedure. Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is preferable due to its once daily administration and a lower risk of heparin induced thrombocytopenia [6].

5.

Fasting from midnight, previously a universal recommendation, is unnecessary and hinders the elective patient’s recovery. Anesthesia guidelines now should recommend fasting for only 2 h for clear fluids and 6 for solids, particulate fluids and those containing fat. Multiple RCTs plus a Cochrane review reveal no resultant increase in complications [24]

6.

Preoperative metabolic stress is reduced in the ‘fed’ patient, leading to decreased postoperative insulin resistance. Preoperative carbohydrate loading with specifically formulated iso-osmolar solutions of 12.5 % dextrose, 2–3 h preoperatively, can reduce post-operative thirst, hunger and anxiety [25]. They result in earlier return of gut function and reduce postoperative hospital stay, especially when compared to fasting [26, 27]. No increase in pulmonary aspiration has been found as gastric emptying is similar to that with water. Postoperative insulin resistance is analogous to a type II diabetic state and is induced by starvation, major stress and immobilization. Thus enhanced recovery care is directed towards avoiding all these triggers [5, 6, 28].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree