CHAPTER 7 Peptic ulcer surgery

Step 1. Surgical anatomy

♦ A dissection of the esophagus at the hiatus will expose the anterior and posterior vagal trunks.

♦ The anterior vagus is intimately related to the anterior esophagus as it traverses from left to right. Circumferential dissection of the vagal trunk will permit placement of surgical clips as well as interval truncal resection for pathologic confirmation.

♦ The posterior vagal trunk has a more variable association to the esophagus but is most often found along the right esophagus between the 7 and 9 o’clock position.

♦ When performing an antrectomy, the gastroduodenal artery should be ligated to ensure proper mobilization of the first and second portion of the duodenum.

♦ The chronic regional inflammation may hinder dissection of the pylorus from the head of the pancreas.

♦ Inadequate mobilization could impair stapling distal to the pylorus and leave retained antrum at the staple line. Retained antrum may lead to recurrent ulcer disease and surgical failure. A full Kocher maneuver is rarely necessary to achieve adequate duodenal mobilization.

Step 2. Preoperative considerations

Patient preparation

♦ The advent of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) has greatly diminished the frequency and volume of peptic ulcer surgery for the practicing general surgeon. Conversely, because of the use and availability of PPIs, only the most severe cases of ulcer disease present for surgical evaluation. A cautious and thorough preoperative workup is paramount.

♦ Patient selection may be the most difficult preoperative activity for the physician. PPI medication noncompliance, chronic NSAID use, smoking, and alcohol use are the most common patient factors that aggravate the disease process. Likewise, these patient factors predict poorer clinical outcomes from surgical intervention. All patients should be counseled appropriately.

♦ The ubiquity of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) has greatly impacted the frequency and volume of peptic ulcer surgery. Additionally, advancements in therapeutic endoscopic techniques, such as pneumatic balloon dilatation, have reduced the need for the classically described antiulcer surgical procedures. Though the frequency of antiulcer operations has dropped, the severity of ulcer disease that prevails often yields the need for surgical evaluation.

♦ The most common indication for vagotomy and pyloroplasty is gastric outlet obstruction caused by chronic and recurring pyloric channel ulcer disease. Most patients will have had one or multiple therapeutic endoscopic procedures, such as pneumatic balloon dilatation. Reviewing the endoscopic procedure history and photographic documentation will enhance not only correct patient selection but also correct procedural selection.

♦ The most common indication for vagotomy and antrectomy is a chronic nonhealing peptic ulcer. In addition to removing any concerning gastric pathology, antrectomy will also improve acid suppression. Depending on the indication, the antrectomy may improve acid suppression and/or remove concerning gastric pathology. Prior to surgical evaluation, patients may have had months of multidrug antiulcer therapy, repeated H. pylori eradication regimens, and numerous ulcer biopsies to rule out occult malignancy. Reviewing the endoscopic procedure history, biopsy pathology results, and procedural photographic documentation will enhance both patient selection and correct procedural selection.

Anesthesia

♦ General endotracheal intubation is recommended for this procedure. The anesthesiologist may insert an orogastric tube to decompress the stomach after induction. Your anesthesia team may prefer a rapid sequence protocol because of the aspiration risk associated with retained gastric contents. Alternatively, if endoscopy is planned as an adjunct to the laparoscopic procedure, therapeutic endoscopic suction and decompression after intubation would be advantageous.

Step 3. Operative steps

Truncal vagotomy with pyloroplasty

Access and port placement

♦ Combining the truncal vagotomy with pyloroplasty makes port site placement different from most other foregut operations. The inferior and right lateral location of the pylorus requires moving the camera and surgeon’s working ports to a more inferior position on the abdomen.

♦ The location for optimal triangulation of the pylorus can be achieved by placing the three trocars in line at the level of the umbilicus. A fourth trocar can be placed in the left subcostal location for an assistant’s instrument. A liver retractor, such as a Nathanson retractor, can be placed though a subxyphoid access site.

Truncal vagotomy

♦ The truncal vagotomy can be performed early in the operation, and often as the first step. Begin by opening the pars flaccida of the gastrohepatic ligament to facilitate identification of the right crus. Division of the phrenoesophageal ligament anterior to the esophagus will permit entry into the mediastinum. A limited dissection of the esophagus at the hiatus will expose the anterior and posterior vagal trunks.

♦ Circumferential dissection of the vagal trunks will permit placement of proximal and distal surgical clips as well as interval truncal resection for pathologic confirmation.

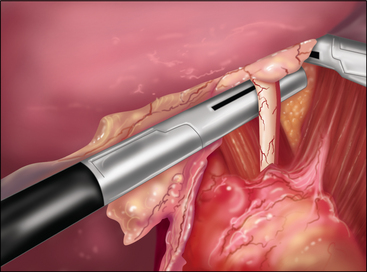

♦ Anterior vagotomy (Figure 7-1).

Pyloroplasty

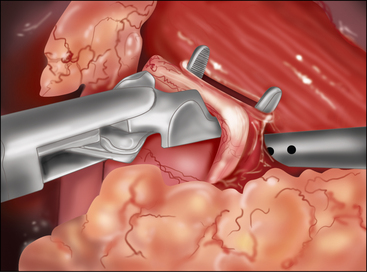

♦ When addressing the pyloroplasty, expect adhesions to the omentum and gallbladder overlying the duodenum resulting from the chronic inflammatory process.

♦ Placement of a superior and inferior traction suture facilitates optimal exposure and control of the tissue. A generous transverse incision should be extending 2 to 3 cm on both sides of the pylorus. The fibrotic and often circumferential nature of this lesion makes the closure difficult. Extending the incision onto soft, pliable tissue of both the antrum and duodenum makes the laparoscopic closure easier. A 4- to 6-cm pyloroplasty should be performed. The longer pyloroplasty will create a larger cross-sectional area that will reduce the risk of postoperative stenosis (Figure 7-3a).

♦ It is important to open the ulcer channel between the antral and duodenal sides of the pylorus. This channel can be short or long, but it is typically very sclerotic and narrow. Endoscopic placement of a transpyloric feeding tube or guidewire greatly facilitates guidance of the enterotomy across the pyloric channel (Figure 7-3b).

♦ Laparoscopic vertical closure of the pyloroplasty is accomplished by a running single full-thickness closure, a Heineke-Mikulicz pyloroplasty. To ensure closure of the incision’s corners, begin separate sutures at the superior and inferior corners, meeting in the center (Figure 7-3c).

♦ Once the pyloroplasty is closed, endoscopic visualization confirms both the patency of the lumen and air tightness of the sutured repair.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree