Pancreas Cancer: Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Albert B. Lowenfels

Patrick Maisonneuve

Introduction

Compared to other digestive tract tumors, pancreatic cancer is infrequent, with an estimated world yearly total of about 230,000 new patients. Approximately 60% of patients live in developed countries, compared to 40% in developing countries. In the United States, there are about 31,000 new cases per year.

Although the tumor is comparatively rare, the survival rate is lower than for other digestive tract tumors and accounts for this tumor being ranked fourth or fifth as a cause of cancer mortality in Western countries. Even with early diagnosis and prompt intervention, nearly all patients who are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer tumor will eventually die from their cancer. A recent review of long-term survivors from the Finnish cancer registry discovered that the original diagnosis of pancreas cancer was often incorrect (1).

An additional difficulty with respect to pancreatic cancer is that it is located in the retroperitoneal space, where direct access for diagnostic purposes is much more difficult than in the tubular parts of the digestive tract. Although there has been substantial progress in visualizing the pancreas with new methodology such as helical computed tomography (CT) scans and endoscopic ultrasound, detecting pancreatic lesions is still not as simple as direct endoscopy, which can easily detect tumors in the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract—the most common sites for digestive cancer.

Descriptive Epidemiology

Globally, pancreatic cancer is a rare tumor; it is much less common than breast, stomach, liver, large bowel, and prostate cancers, which comprise the bulk of world cancer. However, its high mortality makes pancreatic cancer the eighth most common international cause of cancer. Predictably, as lifespan in developing countries increases, this tumor will become even more frequent.

Age-Specific Rates

Similar to other digestive tract cancers, pancreatic cancer rates increase exponentially with age. Indeed, increasing age is the strongest known risk factor for pancreatic cancer; unfortunately, this risk factor is irreversible. The mean age at onset of pancreatic cancer is in the mid-60s, with only 10% of patients developing the tumor at or younger than age 50. In developed countries, cumulative risks (i.e., the probability of developing pancreatic cancer up to a given age, such as 65 or 70 years) is generally <1% for males and slightly less for females. Globally, the cumulative risk is 0.2% for males and 0.1% for females.

At present, surgery offers the best hope for increased survival from pancreatic cancer. However, the bulk of pancreatic cancer unfortunately occurs in elderly patients who often suffer from additional comorbidities, making them unsuitable for surgery. As an example, in New York State for the year 2001, only 15% of all patients with a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer underwent pancreatectomy—the best procedure for increasing survival.

Gender-Specific Differences

There are observable gender-specific differences in the overall frequency of pancreatic cancer (Table 24.1). A small fraction of these differences may be related to hormonal variations between males and females, but because smoking is the best known risk factor for pancreatic cancer, the main cause for the difference has to do with an excess of smoking in males as compared with females.

Racial Differences

Rates for pancreatic cancer are different in different racial groups. Black/white differences are particularly striking. For example, in a study from California, Chang et al. found that pancreatic cancer rates were about 50% higher in African Americans than in Caucasians (Table 24.2). Asian populations had the lowest rates (2). The explanation is not clear but could be due to racial differences in frequency of previously recognized risk factors (3).

Global Differences

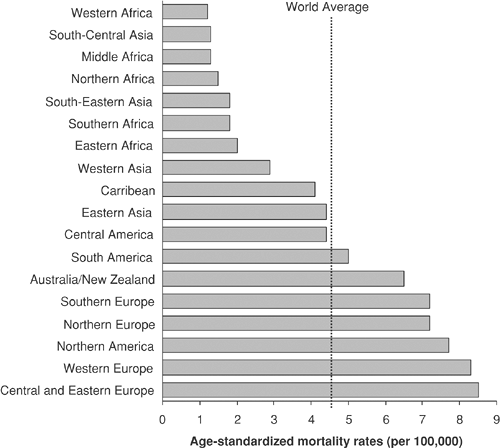

Internationally, there are rather marked differences in mortality rates of pancreatic cancer (Table 24.3, Fig. 24.1). Low rates are found in Africa and parts of Asia; high rates are found in Australia/New Zealand, Europe, and North America. The average world age-standardized mortality rate is about 4.5/100,000/year.

Time Trends

Even in the absence of any treatment-related factors, we can anticipate that there will be changes in the incidence and subsequent mortality of pancreatic cancer. With increasing longevity of population of several non-Western countries such as India

and China added to the already aging populations of Western countries, there will be a global increase in the number of elderly persons where the risk of pancreatic cancer is high. Therefore, based just on demographics, the number of patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer will increase.

and China added to the already aging populations of Western countries, there will be a global increase in the number of elderly persons where the risk of pancreatic cancer is high. Therefore, based just on demographics, the number of patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer will increase.

Table 24.1 Selected age-standardized pancreatic cancer incidence rates per 100,000 by gender and region, 1993–1997 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

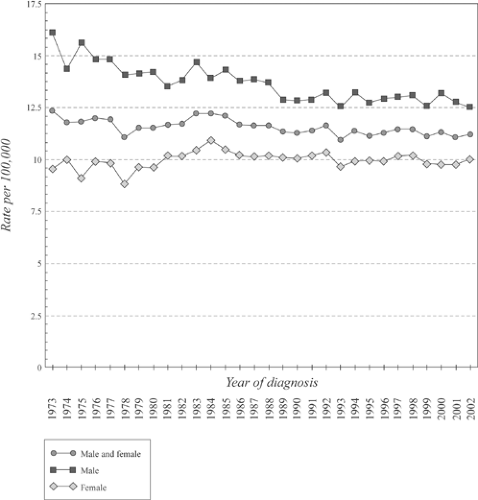

Smoking prevalence is the second important factor that will alter the incidence of pancreatic cancer. In the United States, the incidence of pancreatic cancer has already declined as a result of a decrease in smoking prevalence; this trend is more prominent in males than in females (Fig. 24.2). Several European countries have instituted partial restrictions on smoking that could eventually result in an overall reduction in smoking prevalence. Mulder et al. estimated the absolute reduction in pancreatic cancer deaths in relation to several different smoking scenarios (4). Unlike aging, where the effect of age on incidence will occur rapidly, the beneficial effects of smoking cessation will be more gradual because there is a time lag of 10 years after smoking cessation before the excess risk diminishes (5).

Table 24.2 Race-specific, age-adjusted incidence rates for pancreatic cancer (males and females combined) in California, 1988–1998 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Risk Factors

Smoking

Of the several risk factors that are known to be linked with pancreatic cancer, smoking has been the most extensively studied. Research on smoking and lung cancer published in the 1960s led to an early publication on smoking as a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. Based on a case-control study of 100 patients with biopsy-proven pancreatic tumors and 194 control subjects, Wynder et al. detected a twofold increase in the risk of pancreatic cancer (6). This finding has been confirmed in nearly all subsequent publications that examined the relationship between smoking and lung cancer. The main findings are as follows:

Smokers have a twofold increased risk of pancreatic cancer compared to nonsmokers.

About 25% to 30% of all pancreatic cancer is caused by this single factor.

There is a measurable dose response.

Cigarettes are more harmful than other types of smoking exposure, but other tobacco delivery agents such as smokeless tobacco can cause pancreatic cancer (7,8).

The lag period of approximately 40 years from onset of smoking to onset of pancreatic cancer is somewhat longer than the lag period from smoking to the onset of lung cancer.

Drinking

Heavy consumption of alcohol is the most common known risk factor for chronic pancreatitis, so it is reasonable to assume that alcohol might be a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. However, numerous studies of moderate drinkers have failed to find any link between consuming alcohol and pancreatic cancer. The best explanation is that the pancreas must be less sensitive to the toxic effects of alcohol than, say, the liver, where an occasional moderate drinker develops alcohol-induced cirrhosis eventually leading to liver cancer.

Table 24.3 Estimated world standardized pancreatic cancer mortality rates per 100,000 by gender in different geographic areas, 2002 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

FIGURE 24.1. Estimated world standardized pancreatic cancer mortality rates per 100,000 in different geographic areas, 2002 (males). Source: Data from ref. 49. |

FIGURE 24.2. Age-standardized incidence rates per 100,000 for pancreatic cancer in the United States, 1973–2002. Source: From ref. 66. |

Because heavy drinkers are nearly always heavy smokers, it is likely that any putative association between heavy drinking and pancreatic cancer can be explained by tobacco exposure, rather than by alcohol.

Diet

For many reasons, finding reliable evidence linking diet with pancreatic cancer has been difficult. Because the disease is so aggressive, recruitment of patients for case-control studies has been difficult and is certain to introduce unavoidable biases favoring patients with less aggressive disease. In any event, case-control studies are likely to be less informative than prospective studies, but only a few prospective studies have been performed because they are costly, time consuming, and require extremely accurate follow-up over prolonged time periods. For cancer to develop after any putative risk factor, there must be a prolonged exposure period. This causes a final difficulty—it is difficult to measure early dietary exposure, which is likely to be at least if not more important than recent dietary intake.

In one large prospective study performed in male smokers, a high intake of saturated fat increased the risk of pancreatic cancer by 40%. However, a strange finding in this study was that high intake of energy and carbohydrates lowered the risk (9). In another large prospective study of more than 124,000 persons, Michaud et al. failed to find any relationship between dietary patterns and the risk of pancreatic cancer (10). In contrast, a case-control study performed by Nkondjock et al. found that consumption of fruits and vegetables reduced the risk of pancreatic cancer (11). Omega-3 fatty acids have been suspected to be a beneficial dietary component, but a recent meta-analysis failed to find any reduction in the risk of pancreatic cancer (12).

Do dietary supplements reduce the risk of pancreatic cancer? This important area has been inadequately studied; one report suggests that neither beta-carotene nor alpha-tocopherol have any impact on the risk of pancreatic cancer (13).

Table 24.4 Risk of Pancreatic Cancer Mortality according to Body Mass Index (BMI) Among Males and Females in the Cancer Prevention Study II, 1982–1998 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree