TICK-BORNE DISEASES

Ticks can transmit a variety of infections, including protozoa, bacteria, and viruses. Most of the infections are not primarily hepatic in their manifestations, but the bacterial infections in particular can have liver enzyme elevations. Because of the relative rarity of liver biopsies in the setting of tick-borne disease, the histologic findings are not available in large series from multiple different centers, so the full range of findings is not completely clear. However, a number of helpful case reports and smaller case series have been reported. As an overview, the histologic changes range from mild, nonspecific inflammatory changes to predominately cholestatic changes. Tularemia and Q fever also causes granulomatous inflammation and are discussed in Chapter 7. Three of the tick-borne diseases that are more likely to cause liver dysfunction are individually discussed in the following sections, but all known tick-borne diseases can lead to liver biochemical and histologic abnormalities.3 Clinical findings vary somewhat, but gastrointestinal manifestations are common in many of the tick-borne diseases and can include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and hepatomegaly.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is caused by Rickettsia rickettsii, an organism transmitted by the wood tick and the dog tick. The organism infects endothelial cells throughout the body, and Rocky Mountain spotted fever is a serious illness that can be life-threatening. Early clinical symptoms (in the first 2 to 3 days of illness) are often associated with the gastrointestinal tract and include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The classic findings of fever, headache, rash, and a history of a tick bite often take longer to develop. Risk factors for severe disease include older age, male gender, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency,4 which is most commonly seen in African Americans.

Hepatomegaly with abnormal liver enzymes is commonly seen in symptomatic individuals. The histologic findings are mainly found in the portal tracts and show portal inflammation composed of mixed lymphocytes and neutrophils. The organisms infect the endothelium, and this can result in a portal vein vasculitis as well as fibrin thrombi on liver biopsy. The vasculitis can be largely lymphocytic or can have a neutrophilic component. Vasculitis also affects the stomach, pancreas, and small and large intestine and can lead to significant clinical symptoms. In a small subset of cases, individuals can develop significant cholestasis. Liver biopsies in this setting show predominately cholestasis with mild, nonspecific inflammatory changes.5 In fatal cases, examination of liver tissue has demonstrated prominent sinusoidal erythrophagocytosis as well as inflammatory changes that predominately involving the portal tracts.6,7

Ehrlichiosis

Ehrlichiosis is caused by Ehrlichia and Anaplasma organisms that are transmitted by the lone star tick. The organisms are obligate intracellular bacteria that infect white blood cells. The disease leads to liver dysfunction in greater than 80% of cases, although in most cases, the liver dysfunction is mild, transitory, and largely limited to aminotransferase elevations.3 The livers show lobular cholestasis, which can be marked in severe cases, and is often associated with a diffuse Kupffer cell hyperplasia. The inflammation is typically mild overall, but the individual foci of inflammation can be larger than those usually seen with mild hepatitis, with scattered discrete foci of lymphocytes and macrophages (often 50 to 100 cells in size) associated with hepatocyte necrosis and dropout.8 Larger areas of confluent necrosis have also been reported.8

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is caused by a spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. As with other tick-borne diseases, the clinical gastrointestinal findings at presentation are often nonspecific, with anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. Mild elevations in liver enzymes are commonly present.9,10 Elevated bilirubin levels are rare but have been reported.11

The histologic findings are variable but generally show a mild to moderate hepatitis pattern.12 The lobular infiltrates can contain neutrophils as well as lymphocytes. In one reported case of Lyme disease, the liver biopsy showed large necrotizing granulomas with palisading histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells.13

HEPATIC ABSCESS

Liver abscess can be amebic, fungal, or bacterial. In adults, bacterial (or pyogenic) abscesses are the most common. Risk factors include immunosuppression and chronic biliary tract disease. Bacterial abscesses are also associated with cancer, primarily of the biliary tree or pancreas.14 However, colon cancer is another important association, including nonmetastatic disease.15 The most common organisms are streptococcal or Pseudomonas species, but mixed bacterial and fungal abscesses are common. In children, most hepatic abscesses are due to Staphylococcus aureus.16

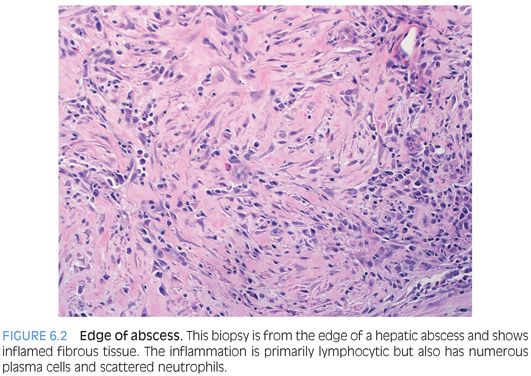

Hepatic abscesses are often not biopsied, because the clinical history and imaging studies can make the diagnosis in many cases. However, a number of abscesses remain undiagnosed by imaging studies and go to liver biopsy. Liver biopsies in these settings typically show a fibrotic rind of tissue surrounding the abscess and occasionally central necrotic tissue. The fibrotic rind is composed of fibrosis with variable amounts of inflammation (Fig. 6.2). The fibrosis itself can vary from dense and hyalinized to loose and edematous. The inflammation is primarily lymphocytic but can have numerous plasma cells as well as admixed eosinophils and neutrophils. Scattered reactive bile ducts are common within the inflamed and fibrotic tissue. The histologic differential is primarily that of an inflammatory pseudotumor. There is sufficient histologic overlap that both should be considered in the differential in most cases. Immunostains are not helpful in this differential. Necrotic debris, often admixed with neutrophilic inflammation, is very helpful in identifying an abscess when present (Fig. 6.3). If there is sampling of the necrotic debris from within the abscess, then stains for fungal organisms or bacteria can help refine the cause of the abscess (eFig. 6.2).