Chapter 29 Other infections involving the liver

1 Primary bacterial infection of the liver is rare. Systemic infections can cause hepatic derangements, ranging from mild liver biochemical test abnormalities to frank jaundice and, rarely, hepatic failure.

3 Schistosomiasis, capillariasis, toxocariasis, and strongyloidosis evoke strong host inflammatory responses and hepatic fibrosis that contribute to the hepatic manifestations.

4 Leishmaniasis and malaria lead to disease primarily through disruption of reticuloendothelial system function.

5 Liver flukes and ascariasis cause cholangitis and biliary hyperplasia; liver fluke infection is associated with cholangiocarcinoma.

Bacterial Infections Involving the Liver

Legionella pneumophila

Pneumonia is the predominant clinical manifestation; abnormal liver biochemical test levels are frequent, usually without jaundice and without affecting the clinical outcome.

Pneumonia is the predominant clinical manifestation; abnormal liver biochemical test levels are frequent, usually without jaundice and without affecting the clinical outcome. Liver histologic features are nonspecific, with portal infiltration, microvesicular steatosis, and focal necrosis; occasional organisms are seen.

Liver histologic features are nonspecific, with portal infiltration, microvesicular steatosis, and focal necrosis; occasional organisms are seen.Staphylococcus aureus (toxic shock syndrome)

This multisystem disease is caused by the staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome toxin (TSST-1) and has a mortality rate of 8%. Originally described in association with tampon use, it is now more frequently a complication of Staphylococcus aureus infections in surgical wounds, mostly in women.

This multisystem disease is caused by the staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome toxin (TSST-1) and has a mortality rate of 8%. Originally described in association with tampon use, it is now more frequently a complication of Staphylococcus aureus infections in surgical wounds, mostly in women. Typical findings include fever, a scarlatiniform rash, mucosal hyperemia, vomiting, diarrhea, and hypotension, with rapid development of multiorgan failure. Hepatic involvement is almost always present, results from hypoperfusion and circulating toxins, and is marked by deep jaundice and high serum aminotransferase levels.

Typical findings include fever, a scarlatiniform rash, mucosal hyperemia, vomiting, diarrhea, and hypotension, with rapid development of multiorgan failure. Hepatic involvement is almost always present, results from hypoperfusion and circulating toxins, and is marked by deep jaundice and high serum aminotransferase levels. Liver histologic findings include microvesicular steatosis, necrosis, and centrilobular cholestasis.

Liver histologic findings include microvesicular steatosis, necrosis, and centrilobular cholestasis. The diagnosis is confirmed by culture of toxigenic S. aureus from vaginal swabs, blood, or other body sites or by demonstration of TSST-1.

The diagnosis is confirmed by culture of toxigenic S. aureus from vaginal swabs, blood, or other body sites or by demonstration of TSST-1.Clostridium perfringens

This is usually a mixed anaerobic infection that results in rapid development of local wound pain, abdominal pain, and diarrhea; it is associated with myonecrosis or gas gangrene.

This is usually a mixed anaerobic infection that results in rapid development of local wound pain, abdominal pain, and diarrhea; it is associated with myonecrosis or gas gangrene. Jaundice may develop in up to 20% of patients with gas gangrene and is predominantly a consequence of massive intravascular hemolysis caused by the bacterial exotoxin, with resulting unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

Jaundice may develop in up to 20% of patients with gas gangrene and is predominantly a consequence of massive intravascular hemolysis caused by the bacterial exotoxin, with resulting unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Liver involvement may include abscess formation and gas in the portal vein. Hepatic involvement does not appear to worsen mortality rates, which average 60%.

Liver involvement may include abscess formation and gas in the portal vein. Hepatic involvement does not appear to worsen mortality rates, which average 60%.Listeria monocytogenes

This is characterized by meningoencephalitis and pneumonitis; hepatic involvement in adult human infection is rare.

This is characterized by meningoencephalitis and pneumonitis; hepatic involvement in adult human infection is rare. Neonates and patients with underlying chronic liver disease or immune deficiency are most commonly affected.

Neonates and patients with underlying chronic liver disease or immune deficiency are most commonly affected. Patients may present with a single abscess, multiple microabscesses, or diffuse or granulomatous hepatitis; the outcome is worse with multiple abscesses.

Patients may present with a single abscess, multiple microabscesses, or diffuse or granulomatous hepatitis; the outcome is worse with multiple abscesses.Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Half of all patients with disseminated gonococcal infection have abnormal liver biochemical test levels, mainly elevated serum alkaline phosphatase levels and elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels. Jaundice is uncommon.

Half of all patients with disseminated gonococcal infection have abnormal liver biochemical test levels, mainly elevated serum alkaline phosphatase levels and elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels. Jaundice is uncommon. Perihepatitis (Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome) is a common complication of gonococcal infection that affects women almost exclusively. It is believed to result from direct spread of infection from the pelvis and does not affect overall outcome. It can also be caused by infection with Chlamydia trachomatis.

Perihepatitis (Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome) is a common complication of gonococcal infection that affects women almost exclusively. It is believed to result from direct spread of infection from the pelvis and does not affect overall outcome. It can also be caused by infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. The sudden onset of sharp right upper quadrant pain, often following lower abdominal pain as an indicator of long-standing pelvic inflammatory disease, is typical. It may be confused with acute cholecystitis or pleurisy.

The sudden onset of sharp right upper quadrant pain, often following lower abdominal pain as an indicator of long-standing pelvic inflammatory disease, is typical. It may be confused with acute cholecystitis or pleurisy. This can be distinguished from gonococcal bacteremia by a characteristic friction rub over the liver and negative blood cultures. The diagnosis is made by vaginal cultures for N. gonorrhoeae. Laparoscopy may show characteristic “violin-string” adhesions between the liver capsule and the anterior abdominal wall.

This can be distinguished from gonococcal bacteremia by a characteristic friction rub over the liver and negative blood cultures. The diagnosis is made by vaginal cultures for N. gonorrhoeae. Laparoscopy may show characteristic “violin-string” adhesions between the liver capsule and the anterior abdominal wall.Burkholderia pseudomallei (melioidosis)

This soil- and water-borne gram-negative bacterium that causes melioidosis is found predominantly in Southeast Asia and India. The clinical spectrum ranges from asymptomatic infection to fulminant septicemia.

This soil- and water-borne gram-negative bacterium that causes melioidosis is found predominantly in Southeast Asia and India. The clinical spectrum ranges from asymptomatic infection to fulminant septicemia. Severe disease involves the lung, gastrointestinal tract, and liver, with hepatomegaly and jaundice; liver histologic changes include inflammatory infiltrates, multiple small and large abscesses, and focal necrosis.

Severe disease involves the lung, gastrointestinal tract, and liver, with hepatomegaly and jaundice; liver histologic changes include inflammatory infiltrates, multiple small and large abscesses, and focal necrosis. Chronic disease is characterized by granulomas with central necrosis resembling tuberculous lesions. Organisms are rarely seen on Giemsa stains of liver biopsy specimens. The diagnosis can be made by serologic testing using an indirect hemagglutination assay.

Chronic disease is characterized by granulomas with central necrosis resembling tuberculous lesions. Organisms are rarely seen on Giemsa stains of liver biopsy specimens. The diagnosis can be made by serologic testing using an indirect hemagglutination assay.Shigella and Salmonella spp.

Cholestatic hepatitis can be attributable to enteric infection with Shigella species; liver histologic findings include portal and periportal polymorphonuclear infiltration, focal necrosis, and cholestasis.

Cholestatic hepatitis can be attributable to enteric infection with Shigella species; liver histologic findings include portal and periportal polymorphonuclear infiltration, focal necrosis, and cholestasis. Typhoid fever caused by Salmonella typhi frequently involves the liver. Some patients may present with acute hepatitis, characterized by fever and tender hepatomegaly. Cholangitis, cholecystitis, and liver abscesses may occur.

Typhoid fever caused by Salmonella typhi frequently involves the liver. Some patients may present with acute hepatitis, characterized by fever and tender hepatomegaly. Cholangitis, cholecystitis, and liver abscesses may occur. Mild to moderate elevations of serum bilirubin (up to 16% of cases) and aminotransferase (up to 60%) levels are common in typhoid fever and should not prompt a search for a separate diagnosis.

Mild to moderate elevations of serum bilirubin (up to 16% of cases) and aminotransferase (up to 60%) levels are common in typhoid fever and should not prompt a search for a separate diagnosis. Hepatic damage appears to be mediated by bacterial endotoxin, which can produce nonspecific reactions, such as sinusoidal and portal inflammation, necrosis, hypertrophy of Kupffer cells, and non-necrotizing granulomas.

Hepatic damage appears to be mediated by bacterial endotoxin, which can produce nonspecific reactions, such as sinusoidal and portal inflammation, necrosis, hypertrophy of Kupffer cells, and non-necrotizing granulomas.Yersinia enterocolitica

This infection manifests as ileocolitis in children and terminal ileitis and mesenteric adenitis in adults.

This infection manifests as ileocolitis in children and terminal ileitis and mesenteric adenitis in adults. Patients with hepatic involvement have underlying comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, cirrhosis, or hemochromatosis; excess tissue iron appears to be a predisposing factor.

Patients with hepatic involvement have underlying comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, cirrhosis, or hemochromatosis; excess tissue iron appears to be a predisposing factor. The subacute septicemic form of the disease resembles typhoid fever or malaria. Multiple abscesses are diffusely distributed in the liver and spleen. The mortality rate approaches 50%.

The subacute septicemic form of the disease resembles typhoid fever or malaria. Multiple abscesses are diffusely distributed in the liver and spleen. The mortality rate approaches 50%.Coxiella burnetii (Q fever)

This is characterized by relapsing fevers, headache, myalgias, malaise, pneumonitis, and culture-negative endocarditis; the liver is commonly affected. The predominant abnormality is an elevated serum alkaline phosphatase level.

This is characterized by relapsing fevers, headache, myalgias, malaise, pneumonitis, and culture-negative endocarditis; the liver is commonly affected. The predominant abnormality is an elevated serum alkaline phosphatase level. The hepatic histologic hallmark is the intra-acinar granuloma with a central fat vacuole surrounded by a fibrin ring and macrophages, the “fibrin-ring granuloma” or “doughnut lesion.”

The hepatic histologic hallmark is the intra-acinar granuloma with a central fat vacuole surrounded by a fibrin ring and macrophages, the “fibrin-ring granuloma” or “doughnut lesion.”Rickettsia rickettsii (Rocky Mountain spotted fever)

Mortality caused by this systemic tick-borne illness has decreased considerably as a result of early recognition; a few patients present with multiorgan manifestations and have a high mortality rate.

Mortality caused by this systemic tick-borne illness has decreased considerably as a result of early recognition; a few patients present with multiorgan manifestations and have a high mortality rate. Hepatic involvement is frequent in multiorgan Rocky Mountain spotted fever, predominantly as jaundice; pathologic examination reveals portal perivascular inflammation and vasculitis.

Hepatic involvement is frequent in multiorgan Rocky Mountain spotted fever, predominantly as jaundice; pathologic examination reveals portal perivascular inflammation and vasculitis.Actinomyces israelii (actinomycosis)

Cervicofacial infection is the most frequent manifestation of actinomycosis, but gastrointestinal involvement is common (13% to 60% of cases).

Cervicofacial infection is the most frequent manifestation of actinomycosis, but gastrointestinal involvement is common (13% to 60% of cases). Hepatic involvement is present in 15% of cases of abdominal actinomycosis, most often as abscesses, and is thought to result from metastatic spread from other abdominal sites through the portal vein. The course is more indolent than that of other causes of pyogenic hepatic abscess (see Chapter 28). Abscesses may be multiple and in both lobes of the liver.

Hepatic involvement is present in 15% of cases of abdominal actinomycosis, most often as abscesses, and is thought to result from metastatic spread from other abdominal sites through the portal vein. The course is more indolent than that of other causes of pyogenic hepatic abscess (see Chapter 28). Abscesses may be multiple and in both lobes of the liver. The diagnosis is based on aspiration of an abscess cavity and visualization of characteristic “sulfur granules” or a positive anaerobic culture.

The diagnosis is based on aspiration of an abscess cavity and visualization of characteristic “sulfur granules” or a positive anaerobic culture.Bartonella bacilliformis (bartonellosis, Oroya fever)

This acute febrile illness is accompanied by jaundice, hemolysis, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy.

This acute febrile illness is accompanied by jaundice, hemolysis, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy.Brucella spp. (brucellosis)

This may be acquired from infected pigs (Brucella suis), cattle (B. abortus), goats (B. melitensis), or sheep (B. ovis).

This may be acquired from infected pigs (Brucella suis), cattle (B. abortus), goats (B. melitensis), or sheep (B. ovis). It manifests as an acute febrile illness with arthralgias, headaches, and malaise or as subacute or chronic disease.

It manifests as an acute febrile illness with arthralgias, headaches, and malaise or as subacute or chronic disease. Hepatomegaly and abnormal liver biochemical test levels are common; jaundice may be present in severe cases. Typically, liver histologic examination shows multiple noncaseating granulomas and, less often, focal portal tract infiltration or fibrosis.

Hepatomegaly and abnormal liver biochemical test levels are common; jaundice may be present in severe cases. Typically, liver histologic examination shows multiple noncaseating granulomas and, less often, focal portal tract infiltration or fibrosis.Spirochetal Infections of the Liver

Leptospira spp. (leptospirosis)

1. This is among the most common zoonoses in the world, with a wide range of domestic and wild animal reservoirs. Human-to-human transmission is uncommon. Up to 80% of the population has been exposed in some tropical countries; it is uncommon in the United States. Human disease can occur as one of two syndromes: anicteric leptospirosis and Weil’s disease.

2. Anicteric leptospirosis accounts for more than 90% of cases. It is characterized by a self-limited biphasic course. A few patients have elevated serum aminotransferase and bilirubin levels with hepatomegaly.

The first phase begins abruptly, with viral illness–like symptoms associated with fever, leptospiremia, and characteristic conjunctival suffusion (an important diagnostic clue) and lasts 4 to 7 days; leptospires are present in the blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

The first phase begins abruptly, with viral illness–like symptoms associated with fever, leptospiremia, and characteristic conjunctival suffusion (an important diagnostic clue) and lasts 4 to 7 days; leptospires are present in the blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The second or immune phase, lasting 4 to 30 days, follows 1 to 3 days of improvement and is characterized by myalgias, nausea, vomiting, abdominal tenderness, and aseptic meningitis in up to 80% of patients.

The second or immune phase, lasting 4 to 30 days, follows 1 to 3 days of improvement and is characterized by myalgias, nausea, vomiting, abdominal tenderness, and aseptic meningitis in up to 80% of patients.3. Weil’s disease is a severe icteric form of leptospirosis and constitutes 5% to 10% of all cases. Complications are mainly the result of direct vascular damage by the Leptospira. The two phases of disease are less distinct:

During the second phase, fever may be high, and hepatic and renal manifestations predominate. Jaundice is marked, with serum bilirubin levels approaching 30 mg/dL. Aminotransferase levels usually do not exceed five times the upper limit of normal, and thrombocytopenia is common. Acute tubular necrosis, which can lead to renal failure, cardiac arrhythmias, and hemorrhagic pneumonitis, are common. Mortality rates range from 5% to 40%.

During the second phase, fever may be high, and hepatic and renal manifestations predominate. Jaundice is marked, with serum bilirubin levels approaching 30 mg/dL. Aminotransferase levels usually do not exceed five times the upper limit of normal, and thrombocytopenia is common. Acute tubular necrosis, which can lead to renal failure, cardiac arrhythmias, and hemorrhagic pneumonitis, are common. Mortality rates range from 5% to 40%.

During the second phase, fever may be high, and hepatic and renal manifestations predominate. Jaundice is marked, with serum bilirubin levels approaching 30 mg/dL. Aminotransferase levels usually do not exceed five times the upper limit of normal, and thrombocytopenia is common. Acute tubular necrosis, which can lead to renal failure, cardiac arrhythmias, and hemorrhagic pneumonitis, are common. Mortality rates range from 5% to 40%.

During the second phase, fever may be high, and hepatic and renal manifestations predominate. Jaundice is marked, with serum bilirubin levels approaching 30 mg/dL. Aminotransferase levels usually do not exceed five times the upper limit of normal, and thrombocytopenia is common. Acute tubular necrosis, which can lead to renal failure, cardiac arrhythmias, and hemorrhagic pneumonitis, are common. Mortality rates range from 5% to 40%.4. The diagnosis of leptospirosis is made on clinical grounds in conjunction with positive cultures of blood or CSF in the first phase or urine in the second phase. Isolation of the organism is difficult and may require many weeks. Microagglutination testing and serologic testing by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) may confirm the diagnosis in the second phase.

5. Liver histologic examination reveals individual hepatocyte damage and canalicular cholestasis with mild portal inflammation.

Treponema pallidum (syphilis)

1. Congenital syphilis

Newborns have characteristic mucocutaneous lesions and osteochondritis, as well as hepatosplenomegaly and jaundice.

Newborns have characteristic mucocutaneous lesions and osteochondritis, as well as hepatosplenomegaly and jaundice.

Newborns have characteristic mucocutaneous lesions and osteochondritis, as well as hepatosplenomegaly and jaundice.

Newborns have characteristic mucocutaneous lesions and osteochondritis, as well as hepatosplenomegaly and jaundice.2. Secondary syphilis

Liver involvement is characteristic (up to 50% of cases) and usually manifests with nonspecific symptoms. Jaundice, hepatomegaly, and right upper quadrant tenderness are less common. Nearly all patients exhibit generalized lymphadenopathy.

Liver involvement is characteristic (up to 50% of cases) and usually manifests with nonspecific symptoms. Jaundice, hepatomegaly, and right upper quadrant tenderness are less common. Nearly all patients exhibit generalized lymphadenopathy.

Biochemical testing generally reveals low-grade elevations of serum aminotransferase and bilirubin levels, with a disproportionate elevation of the serum alkaline phosphatase level.

Biochemical testing generally reveals low-grade elevations of serum aminotransferase and bilirubin levels, with a disproportionate elevation of the serum alkaline phosphatase level.

Liver histologic examination reveals focal necrosis, especially in the periportal and centrilobular regions, or granulomas and portal vasculitis. Spirochetes may be demonstrated by silver staining in up to half of patients.

Liver histologic examination reveals focal necrosis, especially in the periportal and centrilobular regions, or granulomas and portal vasculitis. Spirochetes may be demonstrated by silver staining in up to half of patients.

Liver involvement is characteristic (up to 50% of cases) and usually manifests with nonspecific symptoms. Jaundice, hepatomegaly, and right upper quadrant tenderness are less common. Nearly all patients exhibit generalized lymphadenopathy.

Liver involvement is characteristic (up to 50% of cases) and usually manifests with nonspecific symptoms. Jaundice, hepatomegaly, and right upper quadrant tenderness are less common. Nearly all patients exhibit generalized lymphadenopathy. Biochemical testing generally reveals low-grade elevations of serum aminotransferase and bilirubin levels, with a disproportionate elevation of the serum alkaline phosphatase level.

Biochemical testing generally reveals low-grade elevations of serum aminotransferase and bilirubin levels, with a disproportionate elevation of the serum alkaline phosphatase level. Liver histologic examination reveals focal necrosis, especially in the periportal and centrilobular regions, or granulomas and portal vasculitis. Spirochetes may be demonstrated by silver staining in up to half of patients.

Liver histologic examination reveals focal necrosis, especially in the periportal and centrilobular regions, or granulomas and portal vasculitis. Spirochetes may be demonstrated by silver staining in up to half of patients.3. Tertiary (late) syphilis

Hepatic lesions are common but typically silent. Occasionally, tender hepatomegaly and nodularity may raise the suspicion of metastatic cancer (hepar lobatum).

Hepatic lesions are common but typically silent. Occasionally, tender hepatomegaly and nodularity may raise the suspicion of metastatic cancer (hepar lobatum).

If hepatic involvement is unrecognized, hepatocellular dysfunction and complications of portal hypertension can ensue.

If hepatic involvement is unrecognized, hepatocellular dysfunction and complications of portal hypertension can ensue.

The characteristic lesions in tertiary syphilis are single or multiple gummas with central necrosis, often surrounded by granulation tissue consisting of a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with endarteritis obliterans. Exuberant deposition of scar tissue can ensue. Treponemes are rarely found.

The characteristic lesions in tertiary syphilis are single or multiple gummas with central necrosis, often surrounded by granulation tissue consisting of a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with endarteritis obliterans. Exuberant deposition of scar tissue can ensue. Treponemes are rarely found.

Hepatic lesions are common but typically silent. Occasionally, tender hepatomegaly and nodularity may raise the suspicion of metastatic cancer (hepar lobatum).

Hepatic lesions are common but typically silent. Occasionally, tender hepatomegaly and nodularity may raise the suspicion of metastatic cancer (hepar lobatum). If hepatic involvement is unrecognized, hepatocellular dysfunction and complications of portal hypertension can ensue.

If hepatic involvement is unrecognized, hepatocellular dysfunction and complications of portal hypertension can ensue. The characteristic lesions in tertiary syphilis are single or multiple gummas with central necrosis, often surrounded by granulation tissue consisting of a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with endarteritis obliterans. Exuberant deposition of scar tissue can ensue. Treponemes are rarely found.

The characteristic lesions in tertiary syphilis are single or multiple gummas with central necrosis, often surrounded by granulation tissue consisting of a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with endarteritis obliterans. Exuberant deposition of scar tissue can ensue. Treponemes are rarely found.Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease)

This multisystem disease is caused by the tick-borne spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Predominant manifestations are dermatologic, cardiac, neurologic, and musculoskeletal. Hepatic involvement occurs in 20% of affected patients and usually manifests as hepatomegaly with increased serum aminotransferase and lactate dehydrogenase levels.

This multisystem disease is caused by the tick-borne spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Predominant manifestations are dermatologic, cardiac, neurologic, and musculoskeletal. Hepatic involvement occurs in 20% of affected patients and usually manifests as hepatomegaly with increased serum aminotransferase and lactate dehydrogenase levels. In early stages, the spirochetes disseminate hematogenously from the skin and multiply in the organs of the reticuloendothelial system, including the liver. The clinical picture is suggestive of acute hepatitis and often accompanies erythema chronicum migrans, the sentinel rash.

In early stages, the spirochetes disseminate hematogenously from the skin and multiply in the organs of the reticuloendothelial system, including the liver. The clinical picture is suggestive of acute hepatitis and often accompanies erythema chronicum migrans, the sentinel rash. Liver histologic examination reveals hepatocyte ballooning, marked mitotic activity, microvesicular fat, hyperplasia of Kupffer cells, a mixed sinusoidal infiltrate, and intraparenchymal and sinusoidal spirochetes on Warthin-Starry stain.

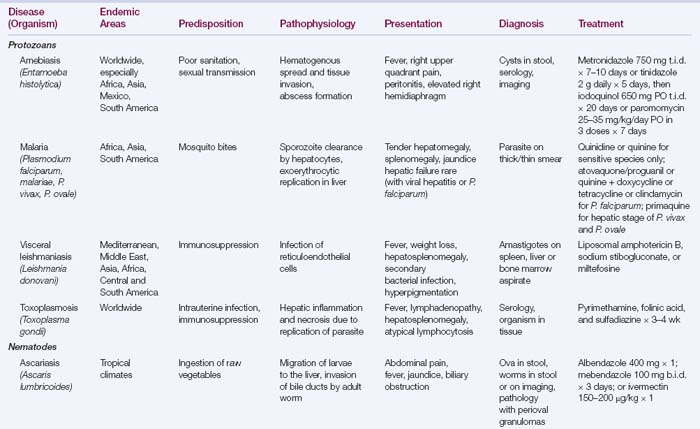

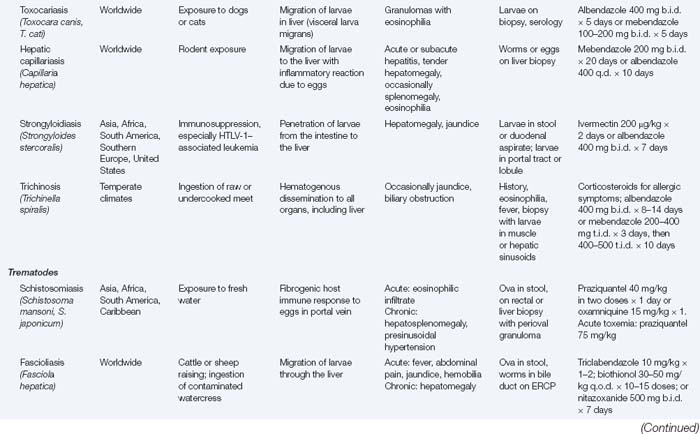

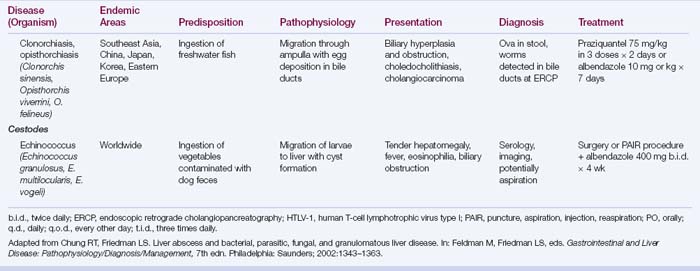

Liver histologic examination reveals hepatocyte ballooning, marked mitotic activity, microvesicular fat, hyperplasia of Kupffer cells, a mixed sinusoidal infiltrate, and intraparenchymal and sinusoidal spirochetes on Warthin-Starry stain.Parasitic Diseases that Involve the Liver (Table 29.1)