Sphere

T = PR/2

Cylinder

T = PR

Camey and LeDuc illustrated this concept in comparing their initial orthotopic diversions. Their first neobladder used tubularized bowel and demonstrated high intraluminal pressures [1]. This problem was remedied with use of detubularized bowel in their later diversions [12].

17.3 Patient Selection

The most common indication for orthotopic urinary diversion is radical cystectomy for muscle invasive urothelial carcinoma (UC). The characteristics of the cancer are critical to choosing the correct diversion, and sound oncological judgment should never be compromised to obtain a better functional outcome. In men, the highest risk for urethral recurrence of UC is in patients who have involvement of the prostatic urethra [13]. While some have advocated pre-cystectomy biopsies of the distal prostatic urethra, it is generally felt that the most accurate information about prostatic involvement comes from intra-operative frozen section. This information is critical to the decision to proceed with neobladder or convert to an ileal conduit. Tumor multifocality, and orthotopic diversion (versus conduit) are also associated with urethral recurrence, but to a much lesser degree than prostatic urethral involvement [13]. Interestingly, carcinoma in situ (CIS) and pathologic stage at radical cystectomy are not predictive of urethral recurrence.

In women, studies have shown that the bladder neck is not necessary to obtain acceptable continence rates after neobladder formation (90 % daytime and 57 % nighttime continence) [14]. Sparing the external urethral sphincter along with creation of a capacious neobladder provides for excellent continence. In terms of cancer control, women with UC or atypia at the bladder neck at the time of cystectomy should be strongly advised against orthotopic diversion [15]. Likewise, UC invasion of the vagina or cervix portends an unacceptably high risk for urethral recurrence and these patients should not receive a neobladder.

Renal and hepatic function are important factors to consider when performing orthotopic neobladder. Use of ileum in the urinary tract carries the risk for hyperchloremic, hypokalemic metabolic acidosis. Urinary solutes, such as urea, potassium, ammonium, and bicarbonate, are absorbed in higher quantities than would be absorbed in an ileal conduit because of the greater surface area. Patients with a creatinine level less than 1.7 mg/dL and an eGFR greater than 35–40 mL/min are considered acceptable candidates for neobladder [16]. Liver function must also be adequate to prevent hyperammonemia with the increased resorption of solute that occurs with a neobladder (See Table 17.2).

Table 17.2

Indications for orthotopic neobladder

Renal funtion: eGFR >35–40 mL/min |

Liver function: low risk of hyperammonemia |

Absence of severe urethral stricture disease |

Absence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) or short-gut syndrome |

Adequate manual dexterity/mental function |

Absence of UC in prostatic urethra (men) or bladder neck (women) |

Impaired rhabdosphincter |

Treatment of other pelvic malignancies, such as prostate and cervical cancer, with pelvic radiation is a common risk factor for bladder cancer [17]. The prevalence of prior radiation in patients undergoing radical cystectomy in large series is approximately 8 % [18]. This predicts a higher long-term incontinence rate and higher perioperative complication rate; however, a neobladder can be safe and effective in a very appropriately selected patient with a history of pelvic radiation [19].

Other factors are also important to the choice of urinary diversion. In general, the overall health status of the patient should be evaluated by the physician to determine if the patient will be able to adequately care for the neobladder. Age is not an absolute contra-indication to neobladder formation but older patients who are debilitated and have multiple medical co-morbidities are often not as dexterous or well suited to maintain a neobladder, especially if SIC is required. An ileal conduit is easier to sustain and eliminates the risk of needing SIC. Urethral stricture disease is not an absolute contraindication for neobladder; however, if the degree of stricture is severe, orthotopic diversion should not be used. Prior prostate or urethral surgery may also add a level of complexity to the urethral dissection and anastomosis, but this does not preclude neobladder formation. Extra care must be taken during the dissection around the urethra in order to maintain the rhabdosphincter. Body mass index (BMI) is another consideration for the type of diversion to be performed. Obese patients may have a fat, short mesentery and when coupled with a thick abdominal wall, an ileal conduit can be difficult to construct. A neobladder in these patients often alleviates these problems and avoids post-operative issues with ischemia to the distal conduit segment. Before neobladder formation in these patients; however, the surgeon must also ensure that part of the bowel segment reaches the pelvis for urethral anastomosis (See Table 17.2).

17.4 Surgical Preparation

Surgical preparation depends on the type of bowel to be used. Use of a bowel prep for ileal diversions has not demonstrated any short or long-term benefit [20]. For neobladders involving colon, a clear liquid diet and full bowel prep the day before surgery are recommended along with an enema 1–2 h before surgery. Colonoscopy is also warranted to rule out malignancy prior to use of this bowel segment.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis is used prior to incision for radical cystectomy and a broad spectrum antibiotic covering skin and enteric flora is also recommended.

17.5 Bowel Segment

Urologists have a variety of options available for orthotopic diversions and each segment has advantages and disadvantages. Surgeon preference is the most important consideration, but this must be adapted to each patient specifically in order to obtain the best outcome possible.

Ileum is the most common segment used in neobladders because it the most compliant and affords the lowest filling pressure [21]. It is easily mobilized into the pelvis and most urologists are familiar with the properties of this bowel. The main disadvantage to use of ileum is the risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency. This is avoided by leaving the distal-most segment of ileum intact. Ileum may also be unacceptable for use because of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). As described earlier, the metabolic abnormality associated with this bowel segment is hyperchloremic hypokalemic metabolic acidosis. Chronically, this can lead to bone demineralization as bone serves as a buffer to chronic acidosis in these patients. Periodic bone mineral density analysis is recommended and bony complications associated with this bowel segment can often be prevented with potassium citrate.

Colon is the second most frequently used bowel segment in orthotopic diversions. Colon is generally less distensible and results in higher pressures than neobladders using ileum alone. Like ileal neobladders, hyperchloremic hypokalemic metabolic acidosis can occur with use of colon and this is also treated with potassium citrate.

Stomach and jejunum are rarely used in orthotopic diversion because of the associated metabolic complications and because of the difficulty mobilizing these segments down into the pelvis for urethral anastomosis. Use of stomach can cause hypochloremic hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis and can result in hematuria dysuria syndrome. Use of jejunum causes hypochloremic hyperkalemic hyponatremic metabolic acidosis and results in severe dehydration.

17.6 Techniques for Orthotopic Diversion

Numerous techniques are used by urologists to fold bowel segments into a reservoir for orthotopic diversion and most of these have acceptable long-term outcomes. The most important consideration for the surgeon is the use of a familiar technique that can be perfected and replicated with each diversion. Generally, the bowel is detubularized to prevent high pressure contractions and non-absorbable suture is avoided to prevent a nidus for stone formation.

Ureteral stents are placed before final closure of the neobladder. The stents are either brought out percutaneously, through the urethra, or left in the bladder and removed cystoscopically later. A suprapubic tube is optional and may be left to maximize drainage during the healing process. An intraperitoneal drain is also left in place to drain any leakage and prevent abscess formation.

We describe some of the most commonly used techniques using ileum for creating a neobladder; however, it should be recognized that there are many other options and variations to the techniques that are described herein.

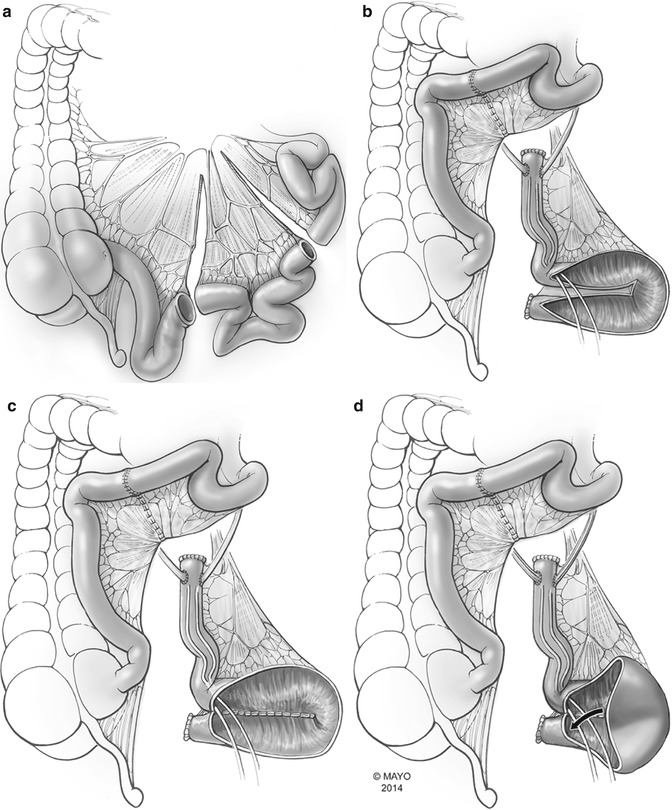

Hautmann “W” Ileal Neobladder

Hautmann first described his technique for neobladder formation in 1988 [2]. Seventy centimeters (cm) of terminal ileum is harvested and folded into a “W” with an equal length for each limb of the W. The bowel is detubularized along the anti-mesenteric border and the inner-most aspect of each limb is sutured together. A buttonhole incision on the distal aspect of one of the limbs is created and the urethral anastomosis completed. The ureters are anastomosed to the neobladder in an end-to-side fashion, and the outside edges of the W are closed to each other in a side-to-side fashion (See Fig. 17.1). The advantages to this technique are the large capacity which decreases nocturnal incontinence, and the ability to leave the ends of the W long if the ureters are short. The main disadvantage also stems from the large size of this diversion. As the neobladder matures and expands with time, patients can experience an increase in absorption of urinary solutes and also have a higher risk of retention.

Fig. 17.1

Hautmann neobladder: a Hautmann neobladder utilizes 70 cm of terminal ileum folded into a W configuration (By permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. All rights reserved)

A variation of this technique, called the serous-lined extra-mural tunnel, was first described by Abol-Enein in dogs and eventually tested in humans [22]. Forty centimeters of terminal ileum are used instead of 70 cm. A trough is made for the ureters between the first and second limbs, as well as the third and fourth limbs of the W. The ureters are then laid into the troughs, spatulated, and anastomosed to the mucosa at the inside corners of the W. The bowel mucosa is then closed over the top of the ureter in each trough, and the neobladder is closed in side-to-side fashion, similarly to Hautmann’s technique. The serous troughs serve as an anti-refluxing mechanism, but also increase the risk of distal ureteral obstruction. A very long ureteral length is necessary for this diversion, so this is not possible unless the distal ureters are free of UC (Fig. 17.1).

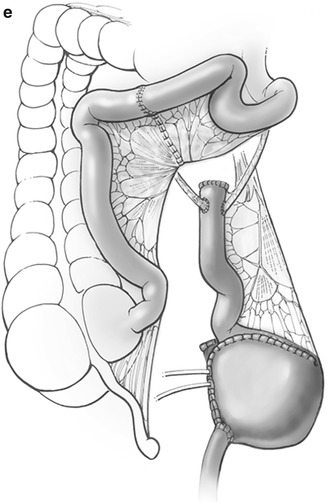

Studer Ileal Neobladder

This neobladder is the most commonly performed orthotopic diversion because it is simple to construct and gives the urologist a great deal of flexibility with the uretero-ileal and urethral anastomoses. A 50–60 cm segment of terminal ileum is isolated, detubularized, and folded into a “U” configuration, leaving the proximal 10–15 cm segment (chimney) tubularized and isoperistaltic for ureteral anastomosis. The bottom half of the U is folded vertically and prior to closure, the urethral anastomosis is performed. The ureters are anastomosed to the chimney with the Bricker or Wallace technique (See Fig. 17.2).