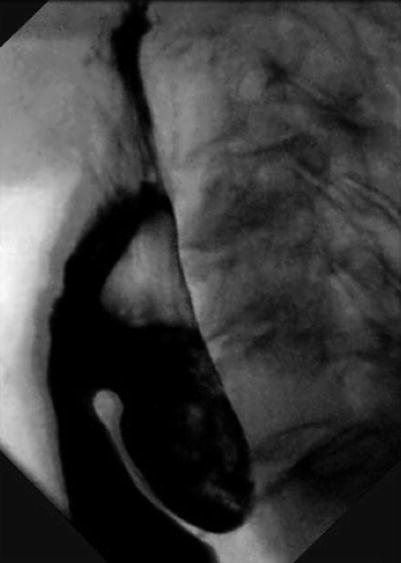

Fig. 11.1

Zenker’s diverticulum, at the junction between the oblique fibers of the cricopharyngeus muscle and the transverse fibers of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor

11.1 Clinical Scenario #1

A 55-year-old woman presented with progressive dysphagia for solids, with a gradual onset 2 years ago. She stated that sometimes she felt as if food got stuck in her neck. She had no odynophagia and no dysphonia, but had nocturnal coughing spells from aspiration of liquid in her trachea. Her husband said that she always has bad breath. A barium swallow showed a 5-cm Zenker’s diverticulum. The patient is otherwise healthy.

11.2 Clinical Scenario #2

A 92-year-old man presented with progressive dysphagia for solids, with a gradual onset 2 years ago. He stated that sometimes he felt as if food got stuck in his neck. He had no odynophagia and no dysphonia, but he has been hospitalized numerous times for chronic aspiration. He has terrible breath odor. A barium swallow showed a 5-cm Zenker’s diverticulum. The patient has had four-vessel coronary artery bypass grafting. He maintains an ejection fraction of 13 % and is on 3 L of oxygen at rest and 6 L when he walks around his house.

11.3 Workup and Choice of Approach

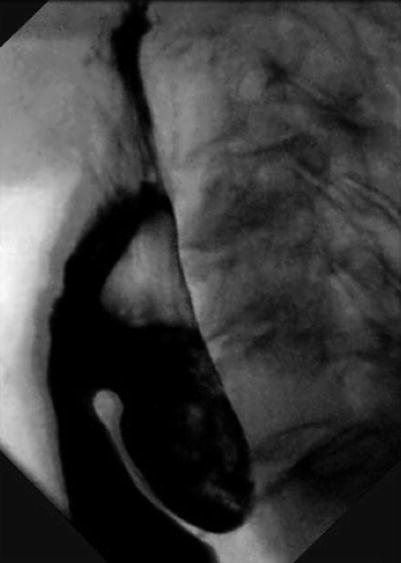

Barium swallow is the diagnostic study of choice. The barium swallow not only can identify the Zenker’s diverticulum (Fig. 11.2), but also can provide more accurate measurements of the distance between the top of the septum and the bottom of the diverticulum than flexible esophagoscopy. Therefore, a barium swallow should be performed in all patients to guide the most appropriate surgical approach.

In patients who also complain of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux, such as regurgitation and heartburn, we perform esophageal function tests to detect reflux objectively. (During these tests, the catheters are inserted under fluoroscopy to avoid perforation of the diverticulum.) In these patients, we perform a laparoscopic fundoplication prior to addressing the Zenker’s diverticulum, in order to stop the reflux and prevent serious episodes of aspiration, which may occur after the transection of the upper esophageal sphincter—the last protective barrier to the gastroesophageal reflux—during the cricopharyngeal myotomy.

The decision to undertake an endoscopic or a transcervical repair depends on the patient’s anatomic characteristics, surgical risk, and the size of the diverticulum. Anatomic characteristics can limit the surgical exposure during the endoscopic repair of Zenker’s diverticulum. A short neck, a short hyomental distance, and a high body mass index correlate significantly with failure of exposure during an endoscopic repair. Furthermore, maxillary dentition, trismus, and preexisting limited motion range of the cervical spine may adversely influence the surgical exposure of the esophagodiverticular septum (common party wall) with the use of the bulky Weerda diverticuloscope. Most patients with Zenker’s diverticulum are in their seventh and eight decades of life and typically have multiple medical comorbidities and a varied degree of surgical risk. Endoscopic repair may be a valid alternative for high-risk patients if there is concern about a longer surgical time during an open surgical approach. Finally, the size of the diverticulum can influence the type of repair. Specifically, a Zenker’s diverticulum with a distance between the top of the septum and the bottom of the diverticulum of less than 3 cm may not be amenable to stapled endoscopic repair because the distal end of the endoscopic stapler is 1.5 cm and is nonfunctional. Endoscopic stapling in these cases may result in an incomplete division of the party wall and an incomplete myotomy, but endoscopic laser myotomy is still feasible.

Fig. 11.2

Barium swallow identifying a Zenker’s diverticulum

11.4 Operation

11.4.1 Operative Planning

In the operating room, the patient is positioned supine on the table and is placed in a 20° reverse Trendelenburg position. The neck is hyperextended by placing a shoulder roll. This maneuver facilitates the insertion of a rigid esophagoscope when an endoscopic approach is planned. If a transcervical approach is planned, the patient’s head is also rotated opposite to the location of the diverticulum to facilitate the surgical exposure of the patient’s neck. Preoperative antibiotics are given before instrumentation of the esophagus. Then, with protection of the maxillary alveolus with a dental guard or moist gauze, we perform a rigid or flexible esophagoscopy to confirm the location of the pouch (usually the left side) and to place a wire guide within the esophageal lumen. (We use the guide wire that is supplied with Savary esophageal dilators.) The wire guide facilitates the placement of the diverticuloscope during the endoscopic approach and can be useful to identify the esophagus in the transcervical approach.

When a transcervical approach is planned, we prefer to pass a 36 Fr Savary dilator over the wire to help identify the esophagus during the operation and to ensure that we do not narrow the lumen when resecting the diverticulum. Additionally, we pack the diverticulum with 1/4-inch ribbon gauze, using a laryngeal forceps inserted through the endoscope, to assist in identification of the diverticulum during the operation. The ribbon gauze is kept long, is taped to the patient’s cheek, and is removed before the stapling of the diverticulum. If the diverticulum is large enough (>4 cm on the preoperative barium swallow), we use the inflated balloon of a 16 Fr Foley catheter (with its tip cut) to aid in the identification of the diverticulum in the operative field.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree