According to evidence-based research and guidelines, behavioral interventions are effective and are recommended as first-line office-based treatment for incontinence and other pelvic disorders. These interventions are aimed at improving symptoms through education on healthy voiding habits and lifestyle modifications. Bladder training techniques are included, which involve progressive voiding schedules together with relaxation and distraction for urgency suppression as well as, pelvic floor muscle strengthening to prevent urine leakage, control urgency, and improve bladder emptying. This article presents the model for providing these treatments in urologic practice and details specifics of each intervention, including education guides for patients.

Key points

- •

Behavioral treatment with pelvic floor muscle training is the first-line treatment option for patients with lower urinary tract symptoms.

- •

Urology lends itself to a multidisciplinary model of a Bladder and Pelvic Floor Disorder service that provides comprehensive surgical and medical care.

- •

Before prescribing a behavioral intervention, assessment of the pelvic floor musculature is performed to evaluate strength, tone, and ability to contract.

- •

Certain lifestyle practices can cause lower urinary tract symptoms, and changes in these practices arising from evidence-based research can have a positive effect in decreasing symptoms.

- •

Bladder training is an education program that teaches the patient to restore normal bladder function by gradually increasing the intervals between voiding.

- •

Pelvic floor muscle training has been shown to decrease urgency, stress, and mixed incontinence in women, and should be offered preoperatively to men undergoing radical prostatectomy surgery.

- •

The best outcomes with behavioral treatments are achieved when they are provided by a knowledgable professional in a supervised program, making it an ideal and necessary service in urology.

Introduction

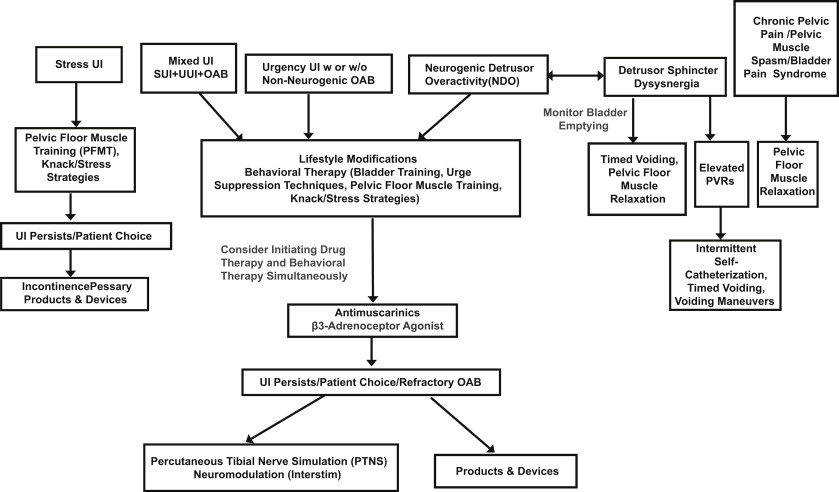

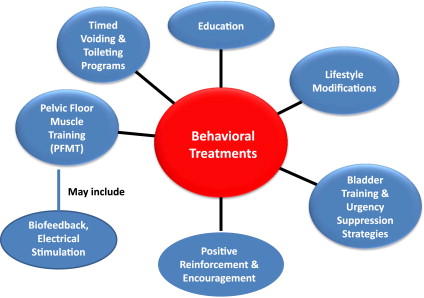

Behavioral treatment with pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is the first-line treatment option for persons with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) including urinary incontinence (UI), overactive bladder (OAB), urgency, frequency, nocturia, incomplete bladder emptying, and pelvic floor muscle (PFM) spasm. These interventions, categorically referred to as conservative management, improve symptoms through pelvic floor muscle strengthening, identification of lifestyle habits, and frequently changing a person’s behavior, environment, or activity that are contributing factors or triggers. Such a program can be initiated after simple non-invasive urologic assessment in most patients, and should be considered the mainstay of urology care of men and women with incontinence and related voiding and pelvic floor disorders. The goals of conservative treatment are to correct voiding patterns, improve the ability to suppress urgency, and thereby to increase bladder capacity and to lessen the frequency and amount of both stress and urgency urinary incontinence. Interventions such as bladder training (BT) and PFM rehabilitation attempt to decrease incontinence and OAB symptoms, and aid bladder emptying through increasing awareness of the function and coordination of the PFMs, so as to gain muscle identification, control, and strength and to decrease bladder overactivity. These interventions involve learning new skills through extensive one-on-one patient instruction on techniques for preventing urine loss, urgency, and other symptomatology. These methods have a large body of evidence-based research, and recommended as treatment for UI which supports this type of program in non-neurogenic OAB by multiple organizations and international guidelines. The behavioral treatments discussed in this article are the ones commonly provided in urology practice for LUTS, and a behavioral treatment pathway is illustrated in Fig. 1 . The different interventions are shown in Fig. 2 , and Box 1 lists the components.

- •

Education on lower urinary tract function, normal voiding, and healthy bladder habits

- •

Behavior modification/coping skills to maximize bladder control

- •

Monitoring symptoms and outcomes through the use of bladder diaries and patient questionnaires

- •

Lifestyle modifications

- •

Bladder training with urgency suppression

- •

Pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation to include biofeedback therapy

- •

Ensure long-term transference of skills learned to the patient’s daily life

- •

Stimulation in refractory patients to include pelvic floor electrical stimulation to increase strength, coordination, and control of bladder and pelvic muscles, and posterior tibial nerve stimulation to decrease urgency and frequency

Introduction

Behavioral treatment with pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is the first-line treatment option for persons with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) including urinary incontinence (UI), overactive bladder (OAB), urgency, frequency, nocturia, incomplete bladder emptying, and pelvic floor muscle (PFM) spasm. These interventions, categorically referred to as conservative management, improve symptoms through pelvic floor muscle strengthening, identification of lifestyle habits, and frequently changing a person’s behavior, environment, or activity that are contributing factors or triggers. Such a program can be initiated after simple non-invasive urologic assessment in most patients, and should be considered the mainstay of urology care of men and women with incontinence and related voiding and pelvic floor disorders. The goals of conservative treatment are to correct voiding patterns, improve the ability to suppress urgency, and thereby to increase bladder capacity and to lessen the frequency and amount of both stress and urgency urinary incontinence. Interventions such as bladder training (BT) and PFM rehabilitation attempt to decrease incontinence and OAB symptoms, and aid bladder emptying through increasing awareness of the function and coordination of the PFMs, so as to gain muscle identification, control, and strength and to decrease bladder overactivity. These interventions involve learning new skills through extensive one-on-one patient instruction on techniques for preventing urine loss, urgency, and other symptomatology. These methods have a large body of evidence-based research, and recommended as treatment for UI which supports this type of program in non-neurogenic OAB by multiple organizations and international guidelines. The behavioral treatments discussed in this article are the ones commonly provided in urology practice for LUTS, and a behavioral treatment pathway is illustrated in Fig. 1 . The different interventions are shown in Fig. 2 , and Box 1 lists the components.

- •

Education on lower urinary tract function, normal voiding, and healthy bladder habits

- •

Behavior modification/coping skills to maximize bladder control

- •

Monitoring symptoms and outcomes through the use of bladder diaries and patient questionnaires

- •

Lifestyle modifications

- •

Bladder training with urgency suppression

- •

Pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation to include biofeedback therapy

- •

Ensure long-term transference of skills learned to the patient’s daily life

- •

Stimulation in refractory patients to include pelvic floor electrical stimulation to increase strength, coordination, and control of bladder and pelvic muscles, and posterior tibial nerve stimulation to decrease urgency and frequency

Behavioral treatment models for LUTS

Urologic diseases encompass a wide scope of illnesses of the genitourinary tract of men and women, including conditions that are congenital and acquired, malignant and benign, medical and surgical. These diseases span all age groups and many conditions (eg, incontinence, voiding dysfunction, benign prostatic hyperplasia) are chronic in nature, and require care for the duration of a patient’s life. With the growing shortage of urologists, the difficulty of recruiting them in some regions of the country, and the aging population, many practices are turning to advanced practice providers (APPs), nurse practitioners, or physician assistants to help fill the need to provide adequate and accessible care. An APP (sometimes referred to as a physician extender), when properly trained and deployed, enables practices to provide an increased number and higher quality of services, and allows the urologist to treat more patients in a timely manner. These highly trained “extenders” can assist the urologist by accepting delegated tasks of greater complexity than had previously been delegated to registered nurses and office assistants with less training.

LUTS (both storage and emptying abnormalities) and pelvic floor dysfunction are areas of urologic practice that have seen tremendous growth in the use of APPs. These conditions have been inadequately treated and poorly addressed by the medical community and industry, despite substantial impact on health, self-esteem, and quality of life. APPs providing behavioral treatments (sometimes referred to as continence nurse practitioners) have emerged in urology practices, specifically to assess and provide nonsurgical treatment of LUTS such as UI, OAB, urgency, frequency, urinary retention, pelvic pain, and interstitial cystitis ( Box 2 ). Urology lends itself to a multidisciplinary model of a Bladder and Pelvic Floor Disorder service that provides comprehensive surgical and medical care. These centers are an attractive addition to a hospital or urology practice because they provide secure revenue-generating services, and there are increasing opportunities for billing of APP services. A Bladder and Pelvic Floor Disorder center usually offers the combined knowledge of a multidisciplinary group of experts in UI, voiding, and pelvic floor dysfunction. Changes in reimbursement for nonsurgical treatments such as biofeedback therapy, pelvic muscle electrical stimulation (E-stim), and posterior tibial nerve stimulation have allowed urologists to consider the expansion of current treatments (pharmacologic and surgical) to include alternative treatments such as PFM rehabilitation.

- •

Comprehensive evaluation of symptoms and associated disorders

- •

Analysis of bladder diaries (pre-, during, and posttreatment) and standardized questionnaires

- •

Instructions on voiding maneuvers (postvoid micturition, improvement in bladder-emptying techniques)

- •

Pelvic floor muscle assessment using a validated scale (pelvic examination, levator ani palpation, anal sphincter muscle assessment)

- •

Bladder training and urge-suppression treatments

- •

Pelvic floor muscle training with the addition of biofeedback and/or pelvic floor muscle electrical stimulation

- •

Pelvic floor muscle “down-training” for pelvic pain and muscle spasm

- •

Medication prescribing

- •

Neuromodulation treatment that includes:

- ○

Programming and management of Interstim

- ○

Delivery of posterior tibial nerve stimulation treatments

- ○

- •

Pessary fitting and maintenance

- •

Catheter management (indwelling catheter [urethral and suprapubic] changes and management, postoperative suprapubic catheter changes, intermittent catheterization teaching and long-term management, urethral stricture catheterization teaching)

- •

Evaluation, fitting, and education on use of external devices (male external catheter, external pouches, toileting-assistive products)

- •

Counseling on absorbent containment products

Assessment before behavioral treatments

Before initiating nonsurgical treatment a focused and detailed history is essential. History is one of the most important steps in evaluating the patient with LUTS, as findings will direct behavioral treatment. Symptoms include urgency, frequency, and nocturia, stress and urgency-related incontinence, postvoid dribbling, nocturnal enuresis, straining to void, hesitancy, weak stream, and incomplete bladder emptying and retention. Understanding the onset, duration, characteristics, and progression of the LUTS is important. Many patients will report situational antecedents or “triggers.”

Appropriate treatment with PFMT should always include an assessment of PFM contraction and relaxation, because the effect of PFMT depends on whether the contractions and relaxations are performed correctly. Digital (eg, vaginal or rectal) PFM assessment is a form of biofeedback performed before starting behavioral therapy. PFM strength can be determined in women by inserting 1 or 2 fingers into the vagina to the level of the first knuckle. Muscular attachments along the pubic arch and the insertion of the levator ani and coccygeus muscles are palpated. The levator ani can be palpated just superior to the hymeneal ring, at the 4- and 8-o’clock positions, to determine strength and whether palpation reproduces any discomfort or tenderness. The patient is asked to contract the PFMs around the examiner’s finger with as much force and for as long as able. The patient is asked to squeeze or pull in and upward with vaginal muscles in short, fast contractions called “flicks.” It is important to realize that when asked to contract the pelvic muscle, women will often use the wrong muscle, strain down, and perform a Valsalva maneuver, or fail to activate all layers of the pelvic musculature. The examiner notes through observation whether accessory muscles (such as gluteal and abdominal muscles) also contract. When assessing PFM strength, 3 criteria should be used and the results noted:

- •

Pressure: the amount of pressure or strength of the muscle contraction, which can range from imperceptible to a firm squeeze

- •

Duration: the number of seconds that the examiner feels the muscle contraction

- •

Alteration in position: in a well-supported PFM, the muscle contraction can lift the base of the examiner’s finger. Note use of accessory muscles (abdominal movement, gluteal lifting). If the patient has a pelvic muscle spasm (inability to relax muscle), note the degree

Assessment of the PFMs in men and women can also be performed by evaluating the contraction and tone of the anal sphincter, and PFM exercises can be taught during the rectal examination. Have the patient relax and bear down. As the sphincter relaxes, gently insert the index finger into the anal canal in a direction pointing toward the umbilicus. Note if the resting sphincter tone is weak, moderate, or strong. Normally, the muscles of the anal sphincter close snugly around the entire circumference of the examiner’s finger. In the rectum, the distal external sphincter is felt just inside the anal canal. The puborectalis portion of the levator ani muscle can be palpated about 2.5 to 4 cm from the anal verge. To assess the strength of the sphincter muscle, ask the patient to tighten the rectum. The examiner should feel a grip, pulling in around entire finger circumference.

Patients are asked to complete a self-monitoring 3-day bladder diary on a daily basis; this is a simple and practical method of obtaining information on voiding behavior. The diary should be constructed in such a way that it provides information regarding sensation of urgency, urine leakage episodes, and the events surrounding these episodes. Before and during treatment, the diary is reviewed to determine voiding patterns: during the day, during the night; frequency of urination; if urine leakage is associated with urgency, or following the ingestion of a bladder irritant such as caffeinated beverages.

Symptoms will direct the interventions. Many providers are interested in the patient noting the type and quantity of absorbent incontinence pads used, and quantifying the amount of urine leakage. An example of a Frequency Volume Bladder Diary is shown in Fig. 3 . Bladder diaries are also the best noninvasive tools available to objectively monitor the effect of treatment. Keeping a diary is thought to empower patients and make them more aware of their drinking and voiding habits, thus helping them to retrain the bladder more effectively.

Behavioral treatments

Education is the initial component of behavioral treatments as patients are taught about the function of the lower urinary tract, the mechanics of bladder storage and emptying, the importance of the urinary sphincter and PFM, and healthy bladder habits. Types of behavior used by women to empty their bladders may be related to the development and worsening of LUTS. These behaviors include:

- 1.

Antecedents: attending to the urge to void, accessing the toilet to empty the bladder, adopting a proper position

- 2.

Micturition: emptying urine into toilet or toilet receptacle, straining

- 3.

Consequences: incomplete bladder emptying, incontinence, bladder control

For example, some women ignore the urge to void and do not urinate while they are at work, delay voiding because of limited work breaks, or have a decreased opportunity to leave their work stations to void. As a result, women may develop a habit of voiding at any time (regardless of the presence of the sensation to void), strain or bear down to void quickly, or void on an infrequent basis. Too frequent voiding makes the bladder more sensitive to a smaller amount of urine within and may, over time, decrease bladder capacity. Overdistension of bladder may occur as a result of infrequent voiding. Behavioral interventions address optimal voiding behavior, posture, and position, to ensure complete bladder emptying ( Patient Guide 1 ).

Maintain Healthy Bladder Habits

Here are some tips on good toileting techniques:

- •

Empty your bladder in a relaxed and private place. Worry and tension can make bladder emptying more difficult.

- •

You should sit on the toilet seat and not “hover” over the toilet, as sitting relaxes your pelvic floor muscles so you can completely empty your bladder.

- •

Sit with your feet flat on the floor. If your feet dangle, place a book under your feet for support.

- •

Breathe gently as you urinate. If possible, minimize bearing down or straining to start your urine stream.

- •

Relax your pelvic floor muscles to start your urine stream.

- •

Do not strain or push down on your bladder with your hands or stomach to help urinate.

- •

Keep your stomach and pelvic floor muscles relaxed while the bladder empties completely.

- •

Make sure your bladder feels completely empty before getting off the toilet.

Moderate your liquid and beverage intake

Many people who have bladder problems will drink less, hoping they will need to urinate less often. Although drinking less liquid does result in less urine in your bladder, a much smaller amount of urine may be more highly concentrated and irritate the lining of your bladder. Concentrated urine (dark yellow, strong smelling) may cause you to go to the bathroom more frequently. Also, drinking too little fluids can cause dehydration. Do not limit your fluids to control your bladder symptoms unless your doctor or nurse tells you to.

Other people may increase the amount they drink because they think more urine in the bladder will cause less bladder pain and discomfort. But drinking too much fluid will cause you to go to the bathroom more often. You should avoid extremes in the amount you drink (neither too much nor too little).

Normal fluid intake is 50 to 70 oz (1 oz = 30 mL) of liquid each day. This means that each day, you should consume the equivalent of 6 to 8 8-oz glasses of liquids (any beverages and soups), much of which can be in the form of solid foods. This should produce a healthy 40 to 50 oz of urine in 24 hours. People who work in hot climates or exercise heavily need more fluids because of loss through perspiration, but their urine output should still be approximately 40 to 50 oz. Do not drink large amounts at one time; instead, sip 2 to 3 oz every 20 to 30 minutes between meals. It is very unlikely that you will need to drink more than 2 quarts (or 8 cups) of total fluids each day.

Monitor your diet and medications

Certain food and beverages can irritate the bladder and make symptoms worse. These include alcoholic beverages, caffeinated foods and/or carbonated beverages (soft drinks, coffee or tea, chocolate, energy drinks), tomato-based products, citrus fruits and juices, spicy foods, and artificial sweeteners (eg, Equal). Also some over-the-counter drugs and prescription medications can worsen bladder problems (eg, Excedrin, Midol, Anacin). Do not stop taking prescription drugs without first talking to your health care provider. Keep a record of what you eat and drink and correlate this with lessening or worsening of your symptoms. Here is the caffeine content of some foods and drugs.

| Size | Caffeine Content (mg) | |

|---|---|---|

| Coffee | 8 oz | 133 (range 102–200) |

| Tea | 8 oz | 53 (range 40–120) |

| Soft drinks | 12 oz | 35–72 |

| Energy drinks | 8–20 oz | 48–300 |

| Chocolate candies | Varies | 9–33 |

| Excedrin (extra-strength) | 2 tablets | 130 |

| Anacin (maximum strength) | 2 tablets | 64 |

| Vivarin, NoDoz | 1 tablet | 200 |

Maintain bowel regularity

Keeping healthy bowel habits may lessen bladder symptoms. Some suggestions include: (1) increase fiber-rich foods in your diet such as beans, pasta, oatmeal, bran cereal, whole wheat bread, fresh fruits and vegetables; (2) exercise to maintain regular bowel movements; (3) drink plenty of nonirritating fluids (water); (4) see your doctor if you have bowel problems.

Maintain a healthy weight

Being overweight can put pressure on your bladder, which may cause leakage of urine when you laugh or cough. If you are overweight, weight loss can reduce pressure on your bladder.

Stop smoking

Cigarette smoking is irritating to the bladder muscle. It can also lead to coughing spasms that can cause urinary leakage.

Lifestyle modifications

In many instances, lifestyle practices can contribute or cause LUTS, bladder and/or pelvic pain. Many lifestyle habits are modifiable and these modifications are part of behavioral treatment. Evidence-based research ( Table 1 ) has shown that lifestyle changes can decrease LUTS. The following are key elements of a lifestyle modification program:

- •

Maintaining adequate fluid intake

- •

Modifying the diet to eliminate possible bladder irritants

- •

Regulating bowel function to avoid constipation and straining during defecation

- •

Smoking cessation

- •

Weight reduction

| Lifestyle Practice | Levels of Evidence | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Fluid | Fluid intake may play a minor role in the pathogenesis of UI | Minor decrease of fluid intake by 25% may be recommended provided baseline consumption is not less than 30 mL/kg a day Grade of Recommendation: B |

| Caffeine | Caffeine consumption may play a role in exacerbating UI. Small clinical trials do suggest that decreasing caffeine intake improves continence Level of Evidence: 2 | Caffeine reduction may help in improving incontinence symptoms Grade of Recommendation: B |

| Bowel function | There is some evidence to suggest that chronic straining may be a risk factor for the development of UI Level of Evidence: 3 | Further research is needed to define the role of straining during defecation in the pathogenesis of UI |

| Obesity | Massive weight loss (15–20 body mass index points) significantly decreases UI in morbidly obese women Level of Evidence: 2 Moderate weight loss may be effective in decreasing UI especially if combined with exercise Level of Evidence: 1 | Weight loss in obese and morbidly should be considered a first-line treatment to reduce UI prevalence Grade of Recommendation: A |

| Smoking | Further prospective studies are needed to determine whether smoking cessation prevents the onset, or promotes the resolution, of UI |

Altering Fluid Intake and Managing Volume

Individuals may practice either restrictive or excessive fluid intake. Working women often report limitations of fluid intake and avoidance of caffeinated beverages as strategies to avoid urinary symptoms. However, adequate fluid intake may be needed to eliminate irritants from the bladder. Underhydration may play a role in the development of urinary tract infections and may decrease the functional capacity of the bladder. Surveys of community-residing elders with LUTS report self-care practices to include the self-imposed fluid restriction, as they fear UI, urinary urgency, and urinary frequency. Excessive fluid intake can also be a problem, as intake of large volumes can trigger incontinence and OAB symptoms of urgency and frequency. Fluid intake averaging greater than 3700 mL/d has been associated with a higher voiding frequency and incidence of UI when compared with an intake of approximately 2400 mL/d. Hashim and Abrams recommend decreasing fluid intake by 25% to reduce frequency, urgency, and nocturia, provided baseline consumption is not less than 1 L a day, and that increasing fluid intake by 25% and 50% can result in a worsening of daytime frequency.

Fluid intake should be regulated to 6- to 8-oz (177–236 mL) glasses or 30 mL/kg body weight per day, with a 1500 mL/d minimum at designated times unless contraindicated by a medical condition.

In older adults, there appears to be a strong relationship between evening fluid intake, nocturia, and nocturnal voided volume. Aging causes an increase in nocturia, defined as the number of voids recorded from the time the individual goes to bed with the intention of going to sleep, to the time the individual wakes with the intention of rising. To decrease nocturia precipitated by drinking fluids primarily in the evening or with dinner, the patient is instructed to reduce fluid intake after 6 pm and shift intake toward the morning and afternoon. Wagg and colleagues recommend that late-afternoon administration of a diuretic may reduce nocturia in persons with lower extremity venous insufficiency or congestive heart failure unresponsive to other interventions.

Influence of Dietary Bladder Irritants

Common dietary staples can cause diuresis or bladder irritability, contributing to LUTS. Up to 90% of patients with IC/BPS report sensitivities to a wide variety of comestibles. Caffeine intake has been associated with LUTS in both men and women. Caffeine is thought to affect urinary symptoms by causing a significant increase in detrusor pressure and an excitatory effect on detrusor contraction. Daily administration of oral caffeine (150 mg/kg) results in detrusor overactivity and increased sensory signaling in the mouse bladder. The consumption of caffeinated beverages, foods, and medications should not be underestimated. In the United States, more than 80% of the adult population consumes caffeine in the form of coffee, tea, soft drinks, and energy drinks on a daily basis. The Boston Area Community Health reported on beverage intake and LUTS in a large cohort (N = 4144). Women who increased coffee intake by at least 2 servings per day had 64% higher odds of progression of urgency ( P = .003). Women who had recently increased soda intake, particularly caffeinated diet soda, had higher symptom scores, urgency, and LUTS progression. Greater coffee or total caffeine intake at baseline increased the odds of LUTS (storage symptoms) progression in men (coffee: >2 cups/d vs none, odds ratio [OR] = 2.09, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.29–3.40, P -trend = .01; caffeine: P -trend<.001). Citrus juice intake was associated with 50% lower odds of LUTS progression in men ( P = .02). Lohsiriwat and colleagues found that caffeine at a dose of 4.5 mg/kg caused diuresis and decreased the threshold of bladder sensation at filling phase, with an increase in flow rate and voided volume. Other findings suggest that high but not stable caffeine intake is associated with a modest increase in the incidence of frequent urgency incontinence. It has been postulated that one-fourth of the cases of urgency and frequency with the highest caffeine consumption would be eliminated if high caffeine intake were eliminated. Confirmation of these findings in other studies is needed before recommendations can be made.

In addition to caffeine, alcohol is also believed to have a diuretic effect that can lead to increased frequency. A survey conducted by the Interstitial Cystitis Network found that 94% of 535 patients who responded reported that their bladder symptoms worsened when drinking various alcoholic beverages. Anecdotal evidence suggests that eliminating dietary factors such as artificial sweeteners (aspartame) and certain foods (eg, highly spiced foods, citrus juices, and tomato-based products) may contribute to LUTS, especially urgency and frequency. Current questionnaire-based data suggest that citrus fruits, tomatoes, vitamin C, artificial sweeteners, coffee, tea, carbonated and alcoholic beverages, and spicy foods tend to exacerbate LUTS, whereas calcium glycerophosphate and sodium bicarbonate tend to improve IC/BPS symptoms.

Assessment of daily caffeine intake on all patients with LUTS and instructions on the correlation between symptoms and caffeine intake are integral to clinical practice. It is recommended that patients with incontinence and OAB avoid excessive caffeine intake (eg, no more than 200 mg/d or 2 cups). The patient is instructed on an elimination diet by identifying possible irritating products on a one-by-one basis to discern whether symptoms decrease or resolve.

Regulating Bowel Function

Chronic constipation (defined as having less than 3 stools per week) and straining during defecation can contribute to LUTS, specifically UI and OAB. Constipation is associated with impaired bladder emptying and worsening of irritative bladder symptoms. The close proximity of the bladder and urethra to the rectum and their similar nerve innervations make it likely that there are reciprocal effects between them. According to Kaplan and colleagues, animal studies and clinical data support bladder-bowel cross-sensitization, or cross-talk between the bowel and bladder. The Epidemiology of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (EpiLUTS) II survey of men and women (N = 2160) aged 40 years or older indicated that OAB is more likely to be reported if either gender had chronic constipation or fecal incontinence, compared with those without OAB. In a case-control study of women with LUTS (n = 820) and matched controls (n = 148), constipation and straining during defecation were significantly more common among the women with LUTS, including detrusor overactivity and urgency, than among the controls. Jelovsek and colleagues reported a 36% overall rate of constipation in women with UI and advanced pelvic organ prolapse.

Lubowski and colleagues reported that denervation of the external anal sphincter and PFMs may occur in association with a history of excessive straining on defecation. Many believe that if these are lifetime habits, they may have a cumulative adverse effect on pelvic floor and bladder function. Patients with LUTS often report self-care practices to cope with LUTS by limiting fluid intake, a strategy that can exacerbate constipation. As combined behavioral and drug therapy is recommended for patients with nonneurogenic OAB, an antimuscarinic can compound the problem. Therefore, as part of the behavioral treatment, an initial approach is to question the patient about bowel habits and, if reported, to manage constipation and normalize defecation. Self-care practices that promote bowel regularity are an integral part of any treatment care plan. Suggestions to reduce constipation include the addition of fiber to the diet, increased fluid intake, regular exercise, external stimulation, and establishment of a routine defecation schedule. High fiber intake must be accompanied by sufficient fluid intake. Improved bowel function can also be achieved by determining a timetable for bowel evacuation so that the patient can take advantage of the urge to defecate.

Smoking and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Conditions exist under which increased intra-abdominal pressure may promote the development of UI and urinary urgency, particularly in women. These conditions include pulmonary diseases such as asthma, emphysema, and chronic coughing, such as seen in persons who smoke and/or have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Coughing causes increased intra-abdominal pressure, which directly increases pressure in the bladder. Usually the sphincter muscle is able to contract tightly to avoid leakage of urine. However, it is thought that persons who cough repetitively cause downward pressure on the pelvic floor resulting in repeated stretch injury to the pudendal and pelvic nerves, and weakening of the ligaments of the PFMs that support the external sphincter, so that incontinence, specifically stress UI (SUI), can occur. Nicotine may contribute to detrusor contractions, and tobacco products may have antiestrogenic hormonal effects that may influence the production of collagen synthesis.

Hrisanfow and Hägglund surveyed 391 women and 337 men (aged 50–75 years) with COPD to determine the prevalence, characteristics, and status of UI. A response rate of 66% was obtained, and most patients had been diagnosed with moderate COPD. The prevalence of UI in this group of men and women with COPD was 49.6% in women and 30.3% in men. Women and men with UI had a significantly higher body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, ie, kg/m 2 ) than those without UI, and the most common type of UI in women was SUI (52.4%) and in men, postmicturition dribbling (66.3%). A United States population-based cohort study of 2109 women aged 40 to 69 years, including racially and ethnically diverse participants, found an adjusted association between a change in continence status and COPD at baseline but not with other comorbidities. There is a significantly increased risk of UI among nonpregnant female heavy smokers, both former and current, compared with women who have never smoked. A cohort study of 523 American women found that smoking before pregnancy in comparison with not smoking gave the highest independent risk for UI postpartum in multivariable analyses (OR = 2.9, 95% CI 1.4–3.9).

No data have been reported that examine whether smoking cessation in women resolves incontinence. However, in a behavioral treatment practice, women who smoke are educated on the relationship between smoking and UI, and strategies designed to discourage women from smoking are often suggested.

Obesity

Obesity is an independent and modifiable risk factor for LUTS in women. There is a large amount of data, including several systematic reviews, demonstrating positive association between a BMI of 25 or greater and SUI as a high risk factor for other urinary tract symptoms including urgency, frequency, OAB, and urge UI (UUI). There is evidence that obesity increases intra-abdominal pressure and places strain and stress on the pelvic floor structures, leading to weakening of the PFM, nerves, and blood vessels, while coexisting metabolic syndrome predisposes to UUI. The resultant impact on vascular perfusion and neural innervation may be a contributing cause of OAB symptoms and incontinence. Moreover, increases in waist circumference are associated with new incidence or progression of current UI. In practice, the authors often see women who have stopped exercising because of LUTS. Weight loss is an acceptable treatment option for morbidly obese women. There is ample evidence-based research to support recommendations of weight loss as part of lifestyle interventions in obese patients with and without diabetes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree