Benign

Acinar cell cystadenoma

Serous cystadenoma, not otherwise specified (NOS)

Premalignant

Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia, grade 3 (PanIN-3)

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) with low- or intermediate-grade dysplasia

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) with high-grade dysplasia

Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm (ITPN)

Mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN) with low- or intermediate-grade dysplasia

Mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN) with high-grade dysplasia

Malignant

Ductal adenocarcinoma

Adenosquamous carcinoma

Mucinous adenocarcinoma

Hepatoid carcinoma

Medullary carcinoma, NOS

Signet-ring cell carcinoma

Undifferentiated carcinoma

Undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like cells

Acinar cell carcinoma

Acinar cell cystadenocarcinoma

Intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma (IPMN) with an associated invasive carcinoma

Mixed acinar-ductal carcinoma

Mixed acinar-neuroendocrine carcinoma

Mixed acinar-neuroendocrine-ductal carcinoma

Mixed ductal-neuroendocrine carcinoma

Mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN) with anassociated invasive carcinoma

Pancreatoblastoma

Serous cystadenocarcinoma, NOS

Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm

Neuroendocrine neoplasms

Pancreatic neuroendocrine microadenoma

Neuroendocrine tumor G1 (NET G1) / Carcinoid

Neuroendocrine tumor G2 (NET G2)

Neuroendocrine carcinoma, NOS

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma

Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma

Enterochromaffin cell (EC), serotonin-producing neuroendocrine tumour (NET)

Gastrinoma, malignant

Glucagonoma, malignant

Insulin-producing carcinoma (insulinoma)

Somatostatinoma, malignant

Lipoma, malignant

Mesenchymal tumors

Lymphangioma, NOS

Lipoma, NOS

Solitary fibrous tumor

Ewing sarcoma

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor

Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm

Lymphomas

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), NOS

Secondary tumors

Metastases

Tumor-like lesions

Acute pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis

Groove pancreatitis

Autoimmune pancreatitis

Cystic lesions

Pancreas divisum

Pancreas annulare

Pancreatic Carcinoma

Most of the various subtypes of pancreatic carcinoma can be differentiated only by histo- and immunopathology.

Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma accounts for 85–95% of all malignant pancreatic tumors (15–20% in gastrointestinal malignancies, 3% in all carcinomas). In general, most of these tumors (60–70%) are located in the pancreatic head, with 15% in the body and 5% in the tail. A multifocal or diffuse tumor spread is uncommon. Prognosis is poor, as most tumors are detected late in an advanced stage of spread. An early metastatic spread along perivascular, ductal, lymphatic, and perineural pathways is promoted by the absence of a true capsule around the organ.

For detection, staging, and follow-up, endoscopic ultrasound (US), contrast-enhanced (CE) CT, MRI, and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDGPET) may be applied [4], whereas [5] endoscopic US presents the highest accuracy in detecting small pancreatichead and periampullary tumors and FDG-PET is superior in detecting distant metastatic spread. Nevertheless, CE-CT and MRI provide a sufficient and comprehensive display of the primary tumor and its sequelae with an accuracy of ~90% and even more [6–8].

The imaging appearance of common pancreatic adenocarcinoma is determined by its typically dense, fibrous, low-vascularized stroma, resulting in low soft-tissue density in CT and low signal on T1- and T2-weighted MRI. No or only minor enhancement (Fig. 1) is what makes the tumors best delineable to the normal glandular parenchyma on CE imaging.

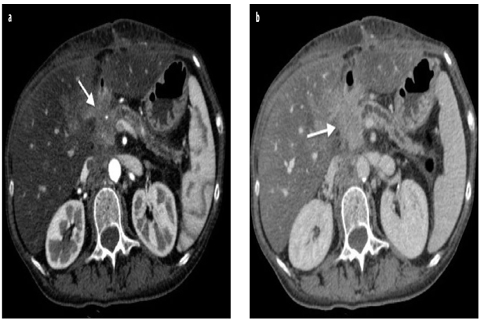

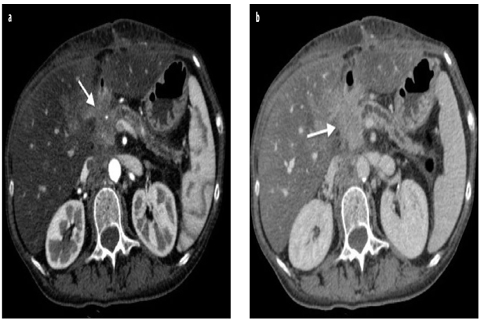

Fig. 1 a, b

Adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas locally invasive. a Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CE-CT) during the pancreatic phase shows a hypovascular focal pancreatic lesion of the head, responsible of infiltration of the main pancreatic duct, with obstructive chronic pancreatitis and infiltration of the peripancreatic fat (arrow). b Axial CE-CT during the portal-venous phase shows infiltration of the posterior peripancreatic fat (arrow)

The pancreatic duct may be involved depending on the primary tumor localization within the pancreas, ranging from no ductal involvement at all in peripheral tumors, to segmental obstruction due to intraductal tumor invasion (duct penetrating sign), to obstruction of both pancreatic and common bile duct (double-duct sign) in pancreatichead tumors. The relation between tumor and ducts is noninvasively seen best on MRCP.

Assessing potential invasive local growth and metastatic spread to local and regional lymph nodes or liver, and vascular invasion completes staging of pancreatic malignancies.

Tumor margins that are blurred and not well defined are still a challenge for every imaging modality, as microscopic local invasive peritumoral spread and an inflammatory desmoplastic reaction often cannot be differentiated, causing over- or underestimation of the T stage [9, 10].

At the time of diagnosis of the primary, about two thirds of patients will present distant metastases (lymph node 40%, hematogenous metastases to the liver 40%, peritoneal metastases 35%), which will be detected with accuracies >90% by CE-MRI and FDG-PET-CT [11, 12]. Moreover, nonresectability in pancreatic cancer is determined by vascular encasement of the superior mesenteric artery, celiac trunk, hepatic or splenic artery, and peripancreatic veins, which is highly likely if a vessel circumference is encased >50% (typical signs: decreased vessel caliber, dilated peripancreatic veins, teardrop shape of superior mesenteric vein).

Other Tumors of Ductal Origin

This heterogeneous group of tumors includes cystic neoplasms, neuroendocrine tumors, and a variety of very rare tumors, such as pancreatoblastoma and solid pseudopapillary neoplasm.

Serous Cystadenoma

Serous cystic neoplasms (SCN) account for ~50% of all cystic tumors, including serous cystadenomas, serous oligocystic adenomas, cystic lesions in von-Hippel-Lindau syndrome, and – rarely – serous cystadenocarcinomas [13]. The most common subtype is the benign serous cystadenoma (microcystic type), typically seen in elderly women (60–80 years of age). In most cases, the lesion is located in the pancreatic head and is composed of multiple tiny cysts separated by thin septae. Spotty calcifications and a central stellate nidus might be present (Fig. 2). About 10% of all serous cystic tumors present as an oligocystic variant, with only a few cysts of 2- to 20-mm diameter and a higher prevalence in men (30–40 years). The rare cystadenocarcinomas are usually large by the time of clinical presentation, with local invasive growth and metastases to lymph nodes and liver. Imaging diagnosis of serous cystic pancreatic lesions is ruled by the proportion of small cysts and septae seen without CE, which may create an almost solid impression on CT, whereas cystic components still can be best appreciated by MRI. Even though the tumors can grow rather large, mismatch of tumor size, missing both ductal involvement and secondary signs of malignancy, will direct to the correct diagnosis. For differentiating oligocystic adenomas from mucinous cystic tumors, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) or walled-off cysts, tumor localization, clean clinical history, and normal ducts on MRCP can be helpful [14, 15].

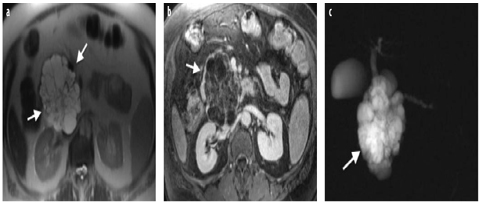

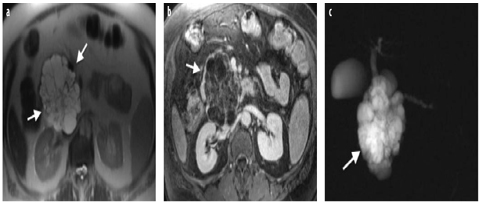

Fig. 2 a–c

Serous cystadenoma. a Axial T2-weighted turbo spin-echo image (TR/TE 4,500/102) shows a multicystic microcystic neoplasm of the head of the pancreas (arrows). b On axial fat-saturated volumetric T1-weighted gradient echo image (TR/TE 4.86/1.87 ms) during the portal-venous phase of the dynamic study following gadolinium-chelate administration, serous cystadenoma shows enhancement of the internal septa and lack of a peripheral wall. c On coronal magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) single-shot rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE) (TR/TE×/110 ms), serous cystadenoma (arrow) is responsible of compression of the main pancreatic duct with upstream dilatation

Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm (MCN)

Mucin-producing cystic tumors, typically in middle-aged women, are characterized by a missing connection to the pancreatic ducts and the histological presence of an ovarianlike stroma. In comparison with SCN, MCN are less frequent (10% of all cystic pancreatic lesions); in general are asymptomatic; detected as solitary, large lesions arising in the body and tail of the pancreas (95%); and composed only of a few cysts with pronounced septae. As the cysts may contain mucinous, hemorrhagic, necrotic, jelly-like material, they may present intermediate and higher densities and signal intensities on CT and MRI, whereas T2- weighted MRI best displays the true cystic structure of the tumor. Nodular enhancement of the septae indicates potential malignancy, which occurs in up to 30% of MCN [16–19].

Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm (IPMN)

Due to increased detection rates by high-resolution imaging, IPMN is considered the most common cystic neoplasm of the pancreas and is seen more often in men than in women [17]. IPMNs may affect the main duct (28%), side branches (46%), or both ductal components (26%) based on a mucin-producing neoplasm arising from the ductal epithelium [20]. The side-branch type can be found as a solitary or multifocal duct dilatation over the entire pancreas and may also form a system of cystic dilated ducts that may mimic a microcystic appearance, as in SCN. Segmental or general dilatation is typical for the main-duct type, creating a chronic pancreatitis-like appearance. In such cases, patient history is the crucial differential diagnostic information. As main-duct-type IPMN has a low malignant potential, at least a thorough follow-up regimen should be recommend in nonsurgical cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree