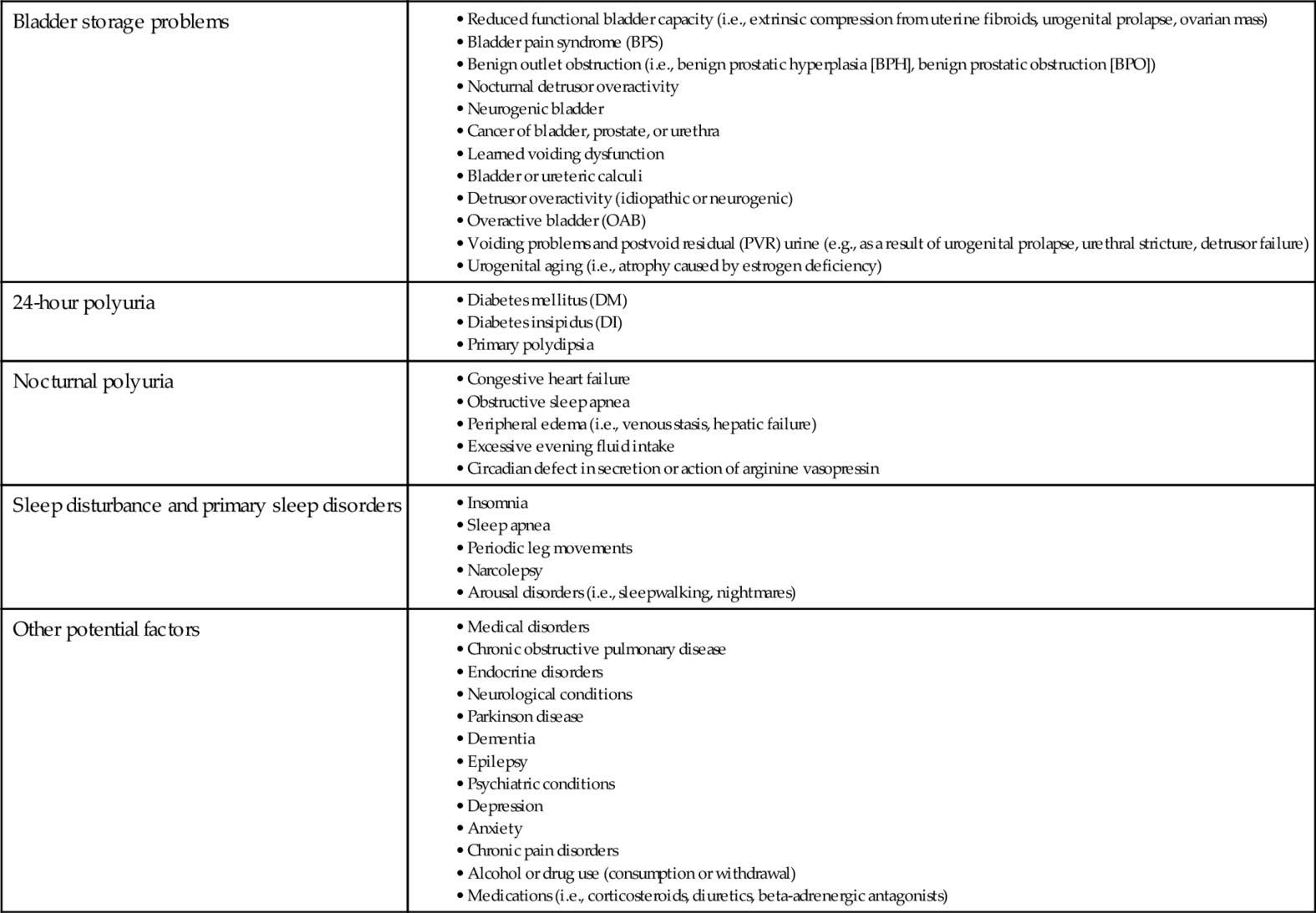

Chapter 13 Nicholas Kavoussi, MD; James M. Weinberger, BS; Jeffrey P. Weiss, MD, FACS This chapter will discuss the epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of nocturia in adults and will act as an aid in the evaluation and treatment of patients with nocturia. The International Continence Society defines nocturia as a urinary storage symptom with the complaint that the individual has to wake one or more times at night to void, with each void being preceded and followed by sleep. Though conceptually easy to use, this definition disregards the clinical relevance of nocturia. By including factors such as bother, impact, or severity of nocturia, the definition might more clearly elaborate the point at which nocturia becomes clinically relevant to evaluate and treat. Regardless of the current definition, a single episode of nocturia should not be disregarded if the patient reports being adversely affected. Population-based studies examining the prevalence of nocturnal voids have shown that 12.5% of men and women from ages 18 to 79 report having at least two voids per night, and up to 40% of the population reports at least one void per night. It is clear that the prevalence of nocturia increases with age and becomes very common in the elderly population. Although the prevalence is greater in young women compared to young men, it increases more strongly with age in men, possibly due to prostatic obstruction in older men or increased sensitivity to arginine vasopressin in women. Several studies suggest an increased prevalence of nocturia in African American men and women compared to other ethnic groups. In an Internet-based survey in the United States, nocturia (at least two voids per night) was reported by 20% of white men, 25% of white women, 25% of Hispanic men, 27% of Hispanic women, 29% of black men, and 37% of black women. Much less is known about ethnicity and nocturia outside of the United States. Little is known about the incidence and natural history of nocturia (particularly in younger men, and women of any age) because few longitudinal studies examine this subject, defining incident nocturia is difficult, and nocturia fluctuates (i.e., it appears and/or resolves). Large population surveys have determined that the need to go to the bathroom is the most common reason for nocturnal awakening. Overall, the degree of bother associated with nocturia is related to both quality and quantity of sleep but is more specifically related to initiating sleep and returning to sleep after awakening. Nocturia has been correlated with daytime fatigue, morbidity, mortality, and decreased quality of life, primarily from sleep disturbance. Although correlation of nocturia with bother and quality of life is clear, causation may not be because insomnia or depression can contribute to interrupted sleep, often followed by a nocturnal void; and snoring, sleep apnea episodes, and leg movements, any of which may disrupt sleep, are associated with nocturia. Determining the number of episodes of nocturnal voids that have an impact on bother and quality of life is essential for evaluating patients. As a generalization, studies suggest that two or more voids per night constitute clinically relevant nocturia, affecting quality of life and perceived health. It has been shown that a single episode of nocturia per night does not have the same detrimental impact on quality of life and perceived health. Although the correlation between nocturia and bother has been defined, there is no definitive distinction regarding how much reduction in nocturia frequency is necessary to relieve said bother. This problem accentuates the difficulty in evaluating effectiveness of nocturia therapies. Nocturia has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality primarily through two mechanisms. First, lack of sleep alters carbohydrate metabolism and endocrine function and is ultimately associated with diabetes. Secondly, nocturia has been associated with higher risk of falls, fractures, and mortality. In elderly populations, falls comprise the greatest risk factor for fractures. The literature suggests that patients with at least two voids per night could have around twice the risk of fractures and mortality. The increased risk of mortality may be an effect of the falls and fractures resulting from middle-of-the-night void attempts, or, alternately, nocturia could simply be an indication of increasing frailty. Increased risk of mortality is not limited to the elderly because some studies show an increase in mortality risk in younger men and women (younger than 65 years). Specifically, the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) found an association between increased mortality risk and two or more voids per night in men and women without comorbid conditions (e.g., heart disease, diabetes). This could imply that nocturia is actually a marker of impending morbidity (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes), which is supported by studies showing a connection between nocturia and chronic illnesses. A few select studies have also examined the impact of nocturia and loss of sleep on productivity in both the workplace and in non–work-related activities. A clear link exists between nocturia and both daytime fatigue and reduced vitality. One particular Swedish study demonstrated that adults with one or more voids per night had impaired work and non-work activity productivity. In normal adults lacking nocturia, the volume of urine excreted by the kidneys at night is less than the functional bladder capacity. Because of this, adults can normally sleep without having to wake up and void. This pattern is established during childhood and is thought in part to be related to the diurnal arginine vasopressin control mechanism. Therefore, for successful urine storage at night, urine needs to be produced and stored in a bladder of adequate capacity to accommodate the volume presented during that defined period. Nocturia has a multifactorial etiology, which often is not urological in origin. The pathophysiology of nocturia can be divided into two broad categories: Primary and secondary nocturia. 2. Primary nocturia can be divided into four broad categories (Table 13-1): b. 24-hour global polyuria characterized by excessive urine production during both day and night. Polyuria is present when 24-hour urine volume exceeds 40 mL/kg. c. Excessive urine production only at night (nocturnal polyuria) in the setting of normal 24-hour urine production is defined as nocturnal urine output exceeding 20% of the total 24-hour urine output (i.e., nocturnal polyuria index, NPi) in the young (age 21 to 35) and exceeding 33% of total 24-hour output in older persons. d. Combinations of the above, otherwise known as mixed etiology, which requires a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and treatment. Table 13-1 Potential Causes or Associated Risk Factors for Nocturia • Bladder pain syndrome (BPS) • Benign outlet obstruction (i.e., benign prostatic hyperplasia [BPH], benign prostatic obstruction [BPO]) • Nocturnal detrusor overactivity • Neurogenic bladder • Cancer of bladder, prostate, or urethra • Learned voiding dysfunction • Bladder or ureteric calculi • Detrusor overactivity (idiopathic or neurogenic) • Overactive bladder (OAB) • Voiding problems and postvoid residual (PVR) urine (e.g., as a result of urogenital prolapse, urethral stricture, detrusor failure) • Urogenital aging (i.e., atrophy caused by estrogen deficiency) • Diabetes insipidus (DI) • Primary polydipsia • Obstructive sleep apnea • Peripheral edema (i.e., venous stasis, hepatic failure) • Excessive evening fluid intake • Circadian defect in secretion or action of arginine vasopressin • Sleep apnea • Periodic leg movements • Narcolepsy • Arousal disorders (i.e., sleepwalking, nightmares) • Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease • Endocrine disorders • Neurological conditions • Dementia • Epilepsy • Psychiatric conditions • Anxiety • Chronic pain disorders • Alcohol or drug use (consumption or withdrawal) • Medications (i.e., corticosteroids, diuretics, beta-adrenergic antagonists) (From Weiss JP, Blaivas JG, Bliwise DL, et al: The evaluation and treatment of nocturia: a consensus statement. BJU Int 108(1):6-21, 2011.) b. Depression: Research suggests that patients with major depression report more nocturia than those without. Furthermore, both major depression and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) therapy are associated with an increased prevalence of nocturia. c.

Nocturia

Introduction

Definitions

Epidemiology

Prevalence

Incidence

Bother and impact on quality of life

Impact of nocturia: falls, fractures, mortality, and productivity

Pathophysiology

Physiology

Etiology

Bladder storage problems

24-hour polyuria

Nocturnal polyuria

Sleep disturbance and primary sleep disorders

Other potential factors

Risk factors

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree