CHAPTER 4 Nissen fundoplication

Step 1. Surgical anatomy

The antireflux barrier

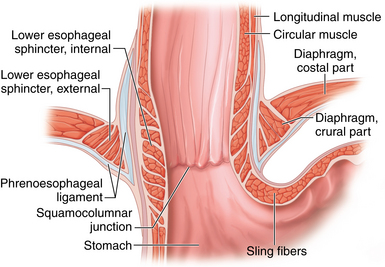

♦ The antireflux barrier of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction depends on proper anatomic alignment of the distal esophagus, proximal stomach, and the diaphragm. The intrinsic muscle fibers of the distal esophagus coordinate with the sling fibers of the cardia and muscle fibers of the diaphragm to prevent reflux of gastric acid into the distal esophagus (Figure 4-1).

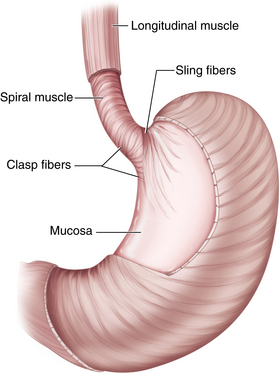

♦ Tonic contraction of the sling and claps fibers of the GE junction works to maintain the acute angle of His. This contributes to the gastroesophageal flap valve mechanism, which further prevents gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) (Figure 4-2).

♦ Restoration of the normal anatomic position of the GE junction and re-creation of the flap valve mechanism through fundoplication are critical elements for a successful antireflux procedure.

Step 2. Preoperative considerations

Patient preparation

♦ In patients with objective evidence of gastroesophageal reflux, the indications for surgery include the following:

Persistent or breakthrough symptoms despite the use of maximal medical therapy (this typically includes patients with volume reflux, or regurgitation)

Persistent or breakthrough symptoms despite the use of maximal medical therapy (this typically includes patients with volume reflux, or regurgitation) Complications of reflux disease, including Barrett’s esophagus, refractory esophagitis, and esophageal strictures

Complications of reflux disease, including Barrett’s esophagus, refractory esophagitis, and esophageal strictures Supralaryngeal symptoms of reflux disease, including chronic cough, aspiration, asthma, or hoarseness

Supralaryngeal symptoms of reflux disease, including chronic cough, aspiration, asthma, or hoarseness Prior to surgical intervention, all patients require upper endoscopy. This provides an opportunity to evaluate the extent of esophagitis and rule out Barrett’s esophagus and gastroesophageal malignancy.

Prior to surgical intervention, all patients require upper endoscopy. This provides an opportunity to evaluate the extent of esophagitis and rule out Barrett’s esophagus and gastroesophageal malignancy. Esophageal manometry is an essential study prior to antireflux surgery to rule out the presence of a severe motility disorder, such as achalasia. This is an important issue, because many of the symptoms of achalasia (regurgitation, heartburn) can mimic those of GERD, whereas the treatment is obviously very different.

Esophageal manometry is an essential study prior to antireflux surgery to rule out the presence of a severe motility disorder, such as achalasia. This is an important issue, because many of the symptoms of achalasia (regurgitation, heartburn) can mimic those of GERD, whereas the treatment is obviously very different. Ambulatory 24-hour esophageal pH studies should be used selectively. Patients with classic reflux symptoms (heartburn and regurgitation) and esophagitis on endoscopy do not require any further evidence of GERD. However, patients with nonerosive disease and those with primarily supralaryngeal symptoms should undergo a 24-hour pH study to document the presence of abnormal reflux.

Ambulatory 24-hour esophageal pH studies should be used selectively. Patients with classic reflux symptoms (heartburn and regurgitation) and esophagitis on endoscopy do not require any further evidence of GERD. However, patients with nonerosive disease and those with primarily supralaryngeal symptoms should undergo a 24-hour pH study to document the presence of abnormal reflux. Upper gastrointestinal fluoroscopic imaging is useful for defining gastroesophageal anatomy in patients who present with dysphagia or who have previously diagnosed large hiatal hernias.

Upper gastrointestinal fluoroscopic imaging is useful for defining gastroesophageal anatomy in patients who present with dysphagia or who have previously diagnosed large hiatal hernias. A gastric emptying study should be considered in patients presenting with significant nausea and vomiting, as these symptoms may suggest of gastroparesis, not GERD.

A gastric emptying study should be considered in patients presenting with significant nausea and vomiting, as these symptoms may suggest of gastroparesis, not GERD.Equipment and instrumentation

♦ We perform the procedure using five ports—three 5-mm ports and two 10-mm ports—as well as a 10-mm, 30-degree angled laparoscope.

♦ A Nathanson retractor is used to elevate the left lateral segment of the liver.

♦ Handheld laparoscopic instruments include atraumatic bowel graspers, scissors, and needle drivers.

♦ We prefer the 5-mm ultrasonic dissector for dissection and hemostasis.

♦ A ¼-inch, 5-cm long Penrose drain is used to facilitate retraction of the esophagus. The ends of the Penrose drain are anchored together anterior to the esophagus using a 0 chromic or Vicryl Endoloop (Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts).

♦ Permanent suture (0 silk or Ethibond, Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) with felt pledgets is used to close the crural defect. The fundoplication is performed with the same suture but without pledgets.

♦ For large crural defects (>4 cm), we use synthetic or biologic mesh to buttress the crural closure.

Anesthesia

♦ Prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism includes the use of sequential lower extremity compression devices and subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin.

♦ Perioperative antibiotics, typically a first-generation cephalosporin, are recommended.

♦ Following induction of general anesthesia, an orogastric tube and Foley catheter are inserted. They can be removed at the conclusion of the procedure.