Neoplastic Lesions of the Anus

General Comments

Anal tumors are predominantly squamous in nature, and while they are rare, they have shown an increase in recent years due to the high prevalence of human papilloma virus (HPV) and HIV infections. Tumors arise in both the anal canal and the perianal areas. These include condylomata, intraepithelial neoplasias, invasive carcinomas, neuroendocrine tumors (see Chapter 17), malignant melanomas, mesenchymal tumors (see Chapter 19), hematologic malignancies (see Chapter 18), and secondary tumors.

Condylomata

Condylomata are benign squamous papillomas caused by HPV infections that exhibit characteristic viral features. They are also commonly referred to as anogenital warts. Of note, while they develop in the anal canal, these tumors are not included in the latest World Health Organization (WHO) classification of anal canal tumors (Table 16.1) (1). Anorectal and perianal condylomata frequently develop in individuals who engage in anal intercourse (2). Their incidence has increased by 50% in recent decades (3), a fact attributed to changes in sexual practices. HIV-infected persons have a high prevalence of anal HPV infections and the neoplasms that develop as a result of the infection. Most patients are male, many of whom admit to having sex with other men. Patients with anal condylomata frequently have coexisting penile, perineal, perianal, anorectal junction, or vulvar lesions. Many patients have recurrent lesions.

Anogenital warts also affect children as the result of increased early sexual activity; sexual abuse; and acquisition of the virus from the tissues of the birth canal at the time of delivery. The anatomic distribution of anal condylomata in children differs from that seen in adults. Seventy-seven percent of boys have perianal disease compared with 8% of adults. Affected children range in age from birth to 17 years, with an average of 5.5 years (4).

Condylomata result from infection by HPV types 1, 2, 6, 7, 10, 11, 16, and 18. HPV 6 and 11 represent the most common HPV types found in genital warts (Fig 16.1) (5). Marked atypia or the presence of carcinoma suggests a coexisting HPV 16 or 18 infection.

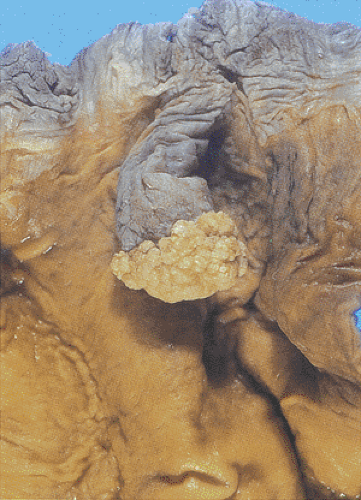

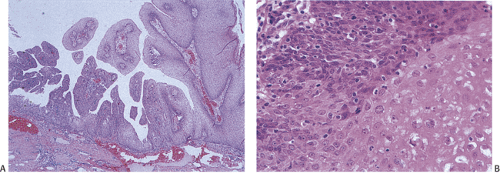

Condylomata develop in the anal transitional zone or on the perianal skin (Figs. 16.2 and 16.3). The gross features vary widely, with the spectrum of lesions ranging from single to multiple growths and from small benign “bumps” to extensive papillary, warty, cauliflowerlike superficial tumors covering large mucosal areas. Tumors that develop in the anal canal tend to have an acuminate or flat gross appearance. Those arising in the perianal areas tend to be more papillary in nature. Fifty percent of patients with perianal warts have condylomata in the anal canal (6). Nonkeratinized condylomata have a characteristic soft pinkish purple appearance, whereas keratinized lesions appear gray-white. Occasional tumors are pigmented. Smaller lesions are smooth, translucent, and almost vesiclelike. Smaller lesions may coalesce into larger ones, especially in immunosuppressed individuals and diabetics.

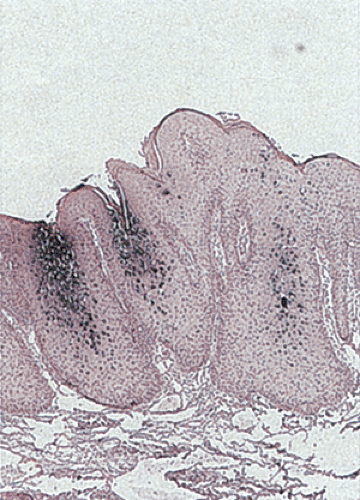

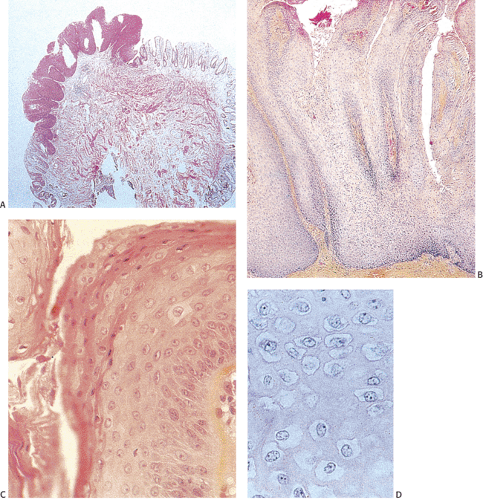

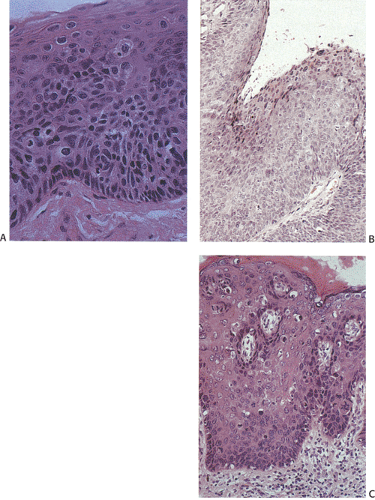

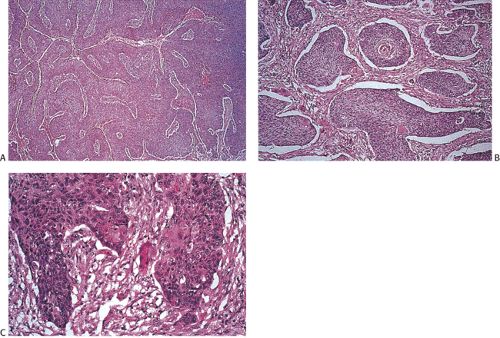

Condylomata consist of benign, acanthotic, papillomatous, squamous growths with variable thickening of the stratum corneum, superficial parakeratosis, and dyskeratosis (Fig. 16.4). The rete ridges appear elongated, broadened, and blunted, mimicking the pattern of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. A normally oriented basal cell layer measuring one to three cells in thickness lies at the base of the neoplastic proliferation. The cells above the basal layer show an orderly progression of squamous cell maturation, a pattern contrasting with the disorderly cellular maturation seen in Bowen disease or squamous cell carcinoma. A well-defined border separates the proliferating squamous epithelium from its underlying supporting stroma. The superficial cells appear large and contain clear cytoplasm with a central hyperchromatic nucleus and perinuclear halo, features known as koilocytosis (Fig. 16.5). Koilocytosis along with anisokaryosis, nuclear hyperchromasia, and the presence of binucleate cells correlate with the presence of HPV. Sometimes koilocytes are absent, perhaps secondary to resolution of the viral infection. Scattered mitotic figures, some of which may appear bizarre, may be present in the acanthotic epithelium. The stroma contains chronic inflammation, and the tissue may appear edematous with vascular dilation.

Some condylomata grow in a flat pattern (Fig. 16.2) similar to that seen in the cervix. Such lesions, sometimes referred to as condyloma planum, show koilocytosis (Fig. 16.5) and

other cytologic features of condylomata but lack the prominent acanthotic growth pattern typical of the more common condyloma acuminatum.

other cytologic features of condylomata but lack the prominent acanthotic growth pattern typical of the more common condyloma acuminatum.

TABLE 16.1 World Health Organization Classification of Anal Carcinomas | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Condylomata may contain areas of intraepithelial neoplasia or invasive carcinomas (Fig. 16.6). The gross appearance cannot be used to distinguish between condylomata with and without areas of high-grade dysplasia or early invasive carcinoma. These diagnoses can only be made following histologic examination of biopsies or resected lesions. Subtle and/or abrupt transitions occur from benign condylomatous areas to the more malignant areas. Areas of typical condyloma, carcinoma in situ, and invasive carcinoma often coexist. With the development of dysplasia, the cells become disorganized, mitoses appear above the basal layer, and the number of dyskeratotic cells increases. Invasive cancers usually develop in the centers of the lesions. The diagnosis of invasive carcinoma is made once the neoplastic cells pass through the basement membrane. Malignant foci are characterized by marked loss of cellular maturation, severe nuclear pleomorphism, an increased nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio, and stromal desmoplasia surrounding invasive cell nests. The histology of the malignant cell populations is discussed further below. There does not appear to be any difference in the biology of condylomata with and without areas of dysplasia in terms of the likelihood of recurrence.

Because of their location, condylomata often become secondarily inflamed, and reactive changes can be mistaken for areas of dysplasia. Inflamed condylomata are characterized by the presence of interstitial inflammation and edema, superficial vacuolization independent of koilocytosis, and variable degrees of basal cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy. In contrast to dysplasia, the basal nuclei do not appear irregular, and they exhibit a more or less orderly pattern of maturation. The nuclei are nonoverlapping, contrasting with areas of intraepithelial neoplasias.

Anal and perianal warts may be treated with podophyllotoxin and/or imiquimod at home or by various surgical or

cryotherapy procedures in the office (7). Venereal warts treated with podophyllin may appear histologically alarming and mimic dysplasia.

cryotherapy procedures in the office (7). Venereal warts treated with podophyllin may appear histologically alarming and mimic dysplasia.

Lesions of the Anal Canal

Intraepithelial Neoplasia

The terminology of anal canal intraepithelial neoplasia has changed over the last few decades. These lesions were originally referred to as squamous dysplasia and carcinoma in situ. In the last edition of this book we termed these lesions anal canal intraepithelial neoplasias. Currently the terminology is evolving to a designation of anal squamous intraepithelial lesions (ASILs) in a manner analogous to the terminology used in the classification of cervical neoplasias. Like cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions (SILs), ASILs are divided into low-grade (LSILs) and high-grade (HSILs) lesions. Indeed, as will be seen, cervical SILs and ASILs share common histologies and etiologies. In all of these lesions the neoplastic cells are confined to the area above the basement membrane.

ASILs originate in both the transitional and squamous zones of the anal canal, often at the squamocolumnar junction, a feature shared with cervical neoplasia. Furthermore, the transitional zone often contains immature squamous epithelium, a cell type that may be particularly vulnerable to infection by high-risk HPV types. HPV infections play a critical role in the development of ASILs and anal carcinoma (8), and an HSIL is considered to be the immediate precursor lesion for invasive squamous cell carcinoma. SILs have been noted in the mucosa adjacent to invasive tumors in 70% to 84% of patients (9,10).

Risk factors for anal HPV infection include HIV positivity (in both men and women), high-risk lifestyles, a history of smoking (11), and organ transplantation. The frequency of HPV in HSILs and LSILs is high among men who have sex with men, especially in those with HIV infections. Approximately 95% of HIV-infected gay men and 65% of HIV-negative gay men develop HPV infections of the anal canal or the perianal skin (12). The prevalence is also high among HIV-positive drug users, and in these patients there may not be a history of anal intercourse (13). The high risk for HPV infections in HIV-infected persons relates in part to the low CD4 cell counts present in these patients. Patients with CD4+ cell counts <500 × 106 cells/L are especially at risk. The benefits of high activity antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in restoring immune function and reducing opportunistic infections means that many patients are living longer than prior to HAART (14). As a result, the incidence of HPV infections and ASILs has increased in HAART-treated patients (15). HPV genotypes 6 and 11 associate with LSILs,

whereas HPV genotypes 16 and 18 associate with HSILs (16). The progression of LSILs to HSILs occurs over a short period of time (2 to 4 years) in HIV-infected homosexual men (12,17). The average age of patients with SILs is younger than that of patients with invasive carcinomas. The relationship of HPV to anal neoplasia is discussed further in the next section.

whereas HPV genotypes 16 and 18 associate with HSILs (16). The progression of LSILs to HSILs occurs over a short period of time (2 to 4 years) in HIV-infected homosexual men (12,17). The average age of patients with SILs is younger than that of patients with invasive carcinomas. The relationship of HPV to anal neoplasia is discussed further in the next section.

The prevalence of ASILs is significantly higher in men with evidence of anal HPV infections, including the presence of anal warts or the presence of flat, white epithelium. In such patients, dysplasia is present in up to 36% of cases by cytologic evaluation and in 92% of patients by biopsy. As many as a third of the patients have HSILs (18). Of women with anal HPV infections, 35.7% have cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN); some also have ASILs. Additionally, vaginal or vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia may extend to the anus. ASILs are also demonstrable in 0.2% to 2.3% of minor surgical specimens, such as hemorrhoids. ASILs are seen with increased frequency in incidental surgical specimens from homosexual men (19).

Patients may present with bleeding or pruritus, or they may remain completely asymptomatic. ASILs may present as eczematoid or papillomatous areas, papules, or macules. Anoscopy facilitates the detection of ASILs and the delineation of their extent. Indigo carmine dye spraying of the mucosa may help define the limits of the lesions (20). Examination of biopsies and cytologic preparations is required to detect or confirm the presence of LSILs and HSILs. Unfortunately, the agreement among pathologists or cytologists for the diagnosis of ASIL is only moderate (21,22).

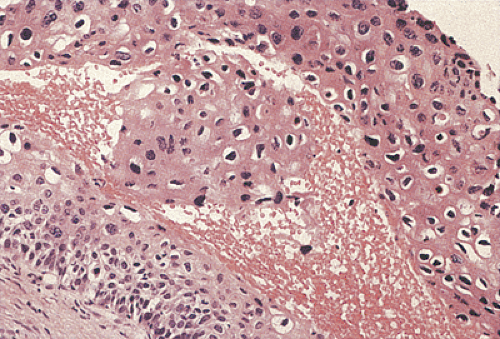

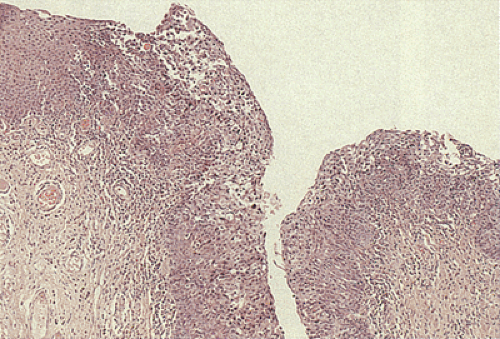

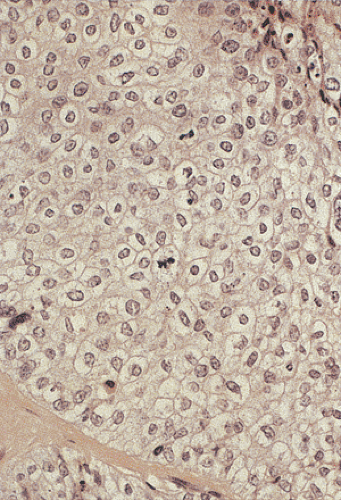

The histologic features of ASILs resemble those of CIN. ASILs consist of a thickened proliferating epithelium (Fig. 16.7) containing undifferentiated cells with a high

nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio extending from the basal layer toward the mucosal surface (5). There is often an abrupt transition between the normal and the dysplastic epithelium. Varying degrees of nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic activity are present. The lesions may or may not show superficial hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis, contrasting with perianal lesions. The cytologically malignant cells lose their normal polarity, overlapping with one another throughout the neoplastic disorderly epithelium. The basal cells appear hyperplastic. The lesions grow in a flat fashion or they form neoplastic acanthotic fingers. Variable thicknesses of the mucosa may be replaced by the neoplastic cells. When the neoplastic proliferation occupies two thirds or more of the mucosal thickness, the lesion is classified as an HSIL. Neoplastic proliferations occupying less than two thirds of the mucosa are classified as an LSIL. Pigmented dendritic cells often lie among the neoplastic cells. A prominent lymphocytic infiltrate may underlie the neoplastic proliferation (Fig. 16.8).

nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio extending from the basal layer toward the mucosal surface (5). There is often an abrupt transition between the normal and the dysplastic epithelium. Varying degrees of nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic activity are present. The lesions may or may not show superficial hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis, contrasting with perianal lesions. The cytologically malignant cells lose their normal polarity, overlapping with one another throughout the neoplastic disorderly epithelium. The basal cells appear hyperplastic. The lesions grow in a flat fashion or they form neoplastic acanthotic fingers. Variable thicknesses of the mucosa may be replaced by the neoplastic cells. When the neoplastic proliferation occupies two thirds or more of the mucosal thickness, the lesion is classified as an HSIL. Neoplastic proliferations occupying less than two thirds of the mucosa are classified as an LSIL. Pigmented dendritic cells often lie among the neoplastic cells. A prominent lymphocytic infiltrate may underlie the neoplastic proliferation (Fig. 16.8).

FIG. 16.8. Sometimes anal intraepithelial neoplasias become markedly infiltrated with lymphocytes as shown in this illustration. |

The neoplastic cells may extend into underlying anal glands. Alternatively, one may see entrapped, normal-appearing anal transitional zone epithelium, not yet replaced by the neoplastic process. The neoplastic cells may also extend into skin appendages. These extensions may reach a median depth of 1.14 mm for involved hair follicles and 1.44 mm for the involved sweat glands with a range up to 2.2 mm. This means that to completely eradicate the disease, tissue destruction or removal must reach a depth of at least 2.2 mm below the adjacent basement membrane (23).

Because of the effectiveness of cervical screening programs in reducing the incidence of cervical neoplasia, the use of anal-rectal cytology (ARC) is increasing in evaluating anal HPV-related diseases in high-risk individuals (men who have sex with men and HIV-infected persons). ARC is an accurate, noninvasive, and cost-effective screening method for ASILs (24). Its sensitivity for detecting biopsy-proven ASILs was 69% in HIV-positive men and 47% in HIV-negative men at the first visit in one study. Repeat cytology increased the sensitivity to 81% and 50%, respectively, in these two groups of men (25). ARC is also used to examine HIV-infected adolescents or those with high-risk sexual behavior (26).

ARC does not require anoscopy or special patient preparation before the examination other than refraining from receptive anal intercourse before the examination. The areas to be sampled should include the anal canal and the area of the anorectal junction, but not the perianal skin. They are collected using a tap water-moistened swab. If the sample is to be examined in a liquid-based cytology preparation, the swab is placed in the preservative vial and agitated to release the harvested cells. Alternatively, the swab can be smeared on a glass slide in a manner analogous to the conventional cervical Pap smear. The cytologic specimens can also be used for oncogenic HPV testing.

ARCs are interpreted according to the Bethesda 2001 guidelines modified for this site. Thus, the cytologic features are divided into atypical squamous cell lesions, LSILs, and HSILs (27). The second edition of the Bethesda System Atlas provides guidelines for specimen interpretation and evaluation of the adequacy of ARC (27). If the specimen contains metaplastic cells and rectal cells, one can be certain that the transitional zone has been sampled. LSILs are characterized by the presence of koilocytes and superficial and high intermediate cells with an increased nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio. Binucleate cells are common. The nuclear membrane is often irregular and angular. Chromatin clumping and hyperchromasia may also be present. Atypical parakeratotic cells may be present, especially in men with increasing degrees of immunodeficiency (28). HSILs consist of intermediate cells or immature squamous metaplastic cells. They have high nuclear:cytoplasmic ratios with nuclear enlargement. Coarse chromatin is present in the nuclei along with irregular wrinkled nuclear membranes. Nucleoli are inconspicuous. These cells may be dispersed singly or arranged in clusters. Parakeratosis is common. Of note, the features of HSILs and invasive carcinoma overlap somewhat since the typical tumor diathesis background picture of invasive cancer is often absent from the invasive anal canal lesions.

HSILs are treated to prevent the development of invasive carcinomas using excisional or ablative techniques (29); some clinicians require complete excision of the lesion with histologically negative margins. However, the lesions may be difficult to remove completely so that recurrences are common. LSILs tend to be followed and some cases spontaneously regress over time.

Anal Canal Carcinomas: General Comments

The terminology for anal carcinomas has been confusing for decades due to the fact that the histology of the anal canal is relatively complex, as discussed in Chapter 15, and the histologies of the tumors can be quite variable. Thus, terms such as cloacogenic, keratinizing or nonkeratinizing squamous, basaloid, transitional, mucoepidermoid, and adenoid cystic carcinomas

have been applied to tumors arising in this site. The reproducibility of these diagnoses was also problematic in part because some of the terms were used interchangeably. A recent study showed that the subdivision of the squamous cell variants that arise in this site has a low level of intra- and interpathologist reproducibility (30). Others have shown that there is little or no prognostic significance in separating these tumors into their variant histologic patterns (31,32,33,34). Furthermore, all of these patterns show an etiologic association with HPV infections. Because of these concerns, the current WHO classification eliminated many of these terms. The current simplified WHO classification of anal tumors is more practical and reproducible (Table 16.1) (1).

have been applied to tumors arising in this site. The reproducibility of these diagnoses was also problematic in part because some of the terms were used interchangeably. A recent study showed that the subdivision of the squamous cell variants that arise in this site has a low level of intra- and interpathologist reproducibility (30). Others have shown that there is little or no prognostic significance in separating these tumors into their variant histologic patterns (31,32,33,34). Furthermore, all of these patterns show an etiologic association with HPV infections. Because of these concerns, the current WHO classification eliminated many of these terms. The current simplified WHO classification of anal tumors is more practical and reproducible (Table 16.1) (1).

Squamous Cell Carcinomas

The vast majority of anal canal carcinomas are squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). These are far more common in the anal canal than in the anal margin (35), and in some ways they are more similar to genital malignancies than they are to other gastrointestinal cancers.

Epidemiology and Patient Demographics

Anal carcinomas are rare tumors, accounting for only 1.5% of gastrointestinal tumors. Studies based on data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program show that anal canal cancer incidence has increased in the United States, especially in cities such as San Francisco, where the incidence has doubled. The incidence of anal cancer in the United States is 0.5 per 100,000 population for men and 0.8 per 100,000 for women (36). The recent increase among men having sex with men suggests that homosexual men belong to an increased–risk group. HPV can be found in 88% to 98% of men having sex with men (37,38,39). The incidence rate for anal cancer for single males is 6.1 times that of married males. This excess is limited to squamous variants (40). There is also an increased incidence among HIV-positive men, despite the introduction of HAART (41). HAART-treated HIV-infected persons are living longer so that it is likely that the natural history of anal HPV infections and anal cancer will change and likely increase. Further, there is evidence that because of the availability of better therapies, individuals are practicing much less safe sex.

Anal canal tumors develop in all adult age groups, but women tend to present in their 5th and 7th decades (31,36). Men between the ages of 20 and 49 have a higher incidence of squamous cell carcinomas than women (36). The age of patients with HPV-related anal tumors is significantly less than that of patients with HPV-negative tumors (42).

Etiology and Predisposing Factors

The etiology of anal SCCs is multifactorial and represents an interaction between both genetic and environmental factors. Decades ago, anal cancer was thought to develop in areas that were chronically inflamed as the result of benign conditions such as fissures, fistulae, hemorrhoids, or Crohn disease (43,44,45,46). Today these factors are not believed to play a major role in the pathogenesis of anal cancer. Numerous epidemiologic studies have shown that the strongest risk factors for anal carcinoma include HPV infection (11,16,47,48), lifetime number of sexual partners (39,49), cigarette smoking (particularly in women) (48), genital warts (a manifestation of HPV infection) (49,50), receptive anal intercourse (11,39,49), and HIV infection (11,51,52,53). The risk of invasive carcinoma in HPV-infected individuals increases in the setting of HIV, perhaps related to the decrease in anal mucosal Langerhans cells (54). Females who engage in anal intercourse show a strong association with the disease (55), as do those with HIV infections (48), previous infection with herpesvirus or Chlamydia trachomatis, or a positive or questionable cervical Pap smear. Squamous cell carcinoma involving the anal canal is more often positive for high-risk HPV (92%) than perianal SCC (64%) (56).

HPV DNA is present in 81% of anal SCCs in both males and females. HPV types 16, 18, and 33 play important etiologic roles in the genesis of the tumors (5). HPV 31, 35, and 51 are also present in some tumors. It is not uncommon to find a mixture of the “benign” HPV 6 or 11 coexisting with the “malignant” HPV 16 and 18 in the same lesion. HPV 16 or 18 infections predispose individuals to increased cancer risk through the accumulation of mutational events that eventually lead to chromosomal instability and the conversion of premalignant to invasive growths. High-risk HPVs encode three oncogenes: E5, E6, and E7. The E6 and E7 viral proteins bind and inactivate the tumor suppressor proteins p53 and Rb, respectively, leading to subsequent uncontrolled cell proliferation (57). E5 is thought to transform cells by modulating growth factor receptors, and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is required for the hyperplastic properties of E5 (58). HPV is more likely to be present in tumors with the following features: Basaloid histology, adjacent SIL, poor or absent keratinization, and a predominance of small or medium-sized tumor cells (51).

Host immune defenses also play an important role in the genesis of anal cancer because anal cancers occur more commonly in immunosuppressed individuals such as HIV-infected and transplant patients. These patients show a strong association with HPV infections, which occur at a younger age; are multifocal, persistent, and recurrent; and progress rapidly (59).

Clinical Features

The signs and symptoms of anal SCCs are often nonspecific, so that 76% of cancers are initially diagnosed as benign lesions. The clinical manifestations relate to tumor size and the extent of mural invasion. Patients with anal cancer present with rectal bleeding, pruritus, pain, discharge, swelling, and perianal ulceration. As the tumors grow, patients develop worsening pain, changes in bowel habits, incontinence, the

sensation of a rectal mass, tenesmus, weight loss, diarrhea, ulceration, incontinence, and fistulae (60). Symptom duration may range up to 4 years, with most patients being symptomatic for more than 6 months (61). Many patients have enlarged inguinal lymph nodes at the time of presentation. Squamous cell carcinomas appear to behave more virulently in men than in women (62).

sensation of a rectal mass, tenesmus, weight loss, diarrhea, ulceration, incontinence, and fistulae (60). Symptom duration may range up to 4 years, with most patients being symptomatic for more than 6 months (61). Many patients have enlarged inguinal lymph nodes at the time of presentation. Squamous cell carcinomas appear to behave more virulently in men than in women (62).

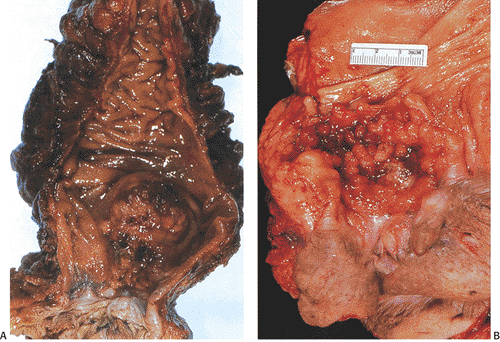

Pathologic Features

Most anal canal SCCs arise at or above the dentate line in the area of the transitional epithelial zone (Fig. 16.9). Larger tumors in the middle or lower canal may grow into the anal orifice, but most anal canal tumors are not visible at this site. Tumors arising in condylomata may appear as indurated polypoid masses or as mucosal or submucosal plaques. They may also appear as an ulcer or fissure with slightly raised indurated margins. The color of the tumor may differ from that of the surrounding mucosa. The tumors range in size from 0.5 cm to up to 15 cm in diameter (63). Larger tumors appear as areas of ulceration or as fungating masses that may become fixed to the underlying structures.

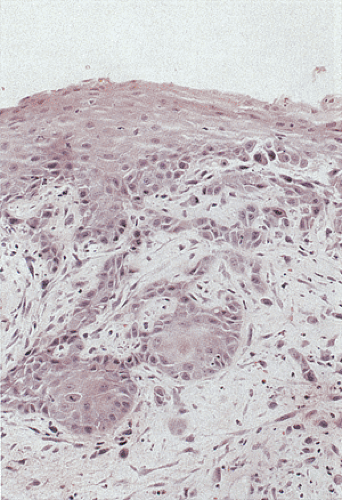

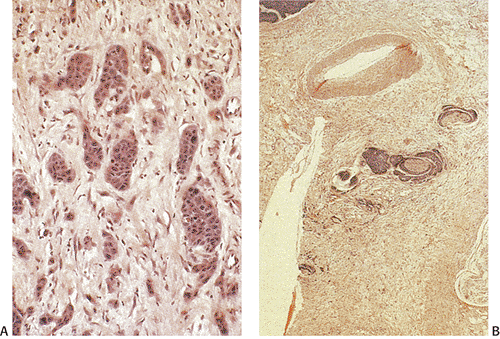

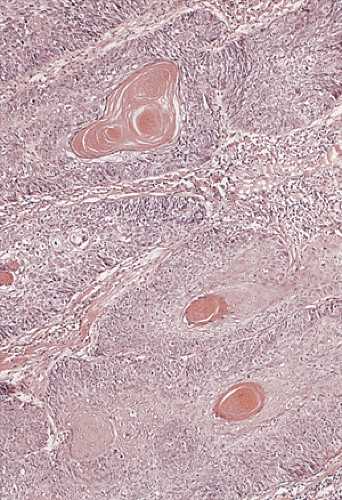

The tumors consist of invasive elongated and angulated tumor nests that contain large pale eosinophilic squamous cells (Fig. 16.10) with or without areas of keratinization. The tumor cells have prominent cytoplasmic borders, but intercellular

junctions are often absent. The cells may contain a clear or granular cytoplasm. Better differentiated tumors may demonstrate peripheral palisading, a pattern that disappears as the tumors become less differentiated. Central necrosis may be present. The hyperchromatic nuclei appear round, ovoid, and vesicular, containing numerous mitotic figures. Rarely, keratinizing large cell SCC components are present (Fig. 16.11). Basaloid areas may be present. These consist of small to intermediate-sized basaloid cells with minimal keratinization, peripheral palisading, comedolike necrosis in the center of the lobular tumor islands (Fig 16.12), and the possible deposition of basement membrane–like material (which imparts an adenoid cystic–like pattern) (64). Tumor areas resembling adenoid cystic carcinoma may show prominent perineural invasion (Fig. 16.13). The basaloid areas are compared to perianal basal cell carcinomas in Table 16.2. The cells of what was previously termed transitional cell carcinoma consist of larger elongated cells containing plentiful clear (Fig. 16.14) or slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm arranged in anastomosing cords and islands that are sharply demarcated from the surrounding stroma. The cells at the epithelial stromal junction may show an attempt at palisading. Tumors that contain foci of mucin secretion or small mucin lakes were previously termed mucoepidermoid carcinomas (Fig. 16.15); they are currently termed squamous cell carcinomas with mucinous microcysts (1).

Sarcomatoid carcinomas (65) and anal clear cell variants also occur (66).

junctions are often absent. The cells may contain a clear or granular cytoplasm. Better differentiated tumors may demonstrate peripheral palisading, a pattern that disappears as the tumors become less differentiated. Central necrosis may be present. The hyperchromatic nuclei appear round, ovoid, and vesicular, containing numerous mitotic figures. Rarely, keratinizing large cell SCC components are present (Fig. 16.11). Basaloid areas may be present. These consist of small to intermediate-sized basaloid cells with minimal keratinization, peripheral palisading, comedolike necrosis in the center of the lobular tumor islands (Fig 16.12), and the possible deposition of basement membrane–like material (which imparts an adenoid cystic–like pattern) (64). Tumor areas resembling adenoid cystic carcinoma may show prominent perineural invasion (Fig. 16.13). The basaloid areas are compared to perianal basal cell carcinomas in Table 16.2. The cells of what was previously termed transitional cell carcinoma consist of larger elongated cells containing plentiful clear (Fig. 16.14) or slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm arranged in anastomosing cords and islands that are sharply demarcated from the surrounding stroma. The cells at the epithelial stromal junction may show an attempt at palisading. Tumors that contain foci of mucin secretion or small mucin lakes were previously termed mucoepidermoid carcinomas (Fig. 16.15); they are currently termed squamous cell carcinomas with mucinous microcysts (1).

Sarcomatoid carcinomas (65) and anal clear cell variants also occur (66).

FIG. 16.11. Squamous cell anal canal carcinoma. Note the prominent central keratinization. The surrounding stroma is desmoplastic. |

SCCs often show a progression of squamous cell lesions that may include condylomata, SILs, and invasive carcinoma. In other instances, the tumor appears to “drop off” an overlying more or less normal-appearing squamous epithelium (Fig. 16.16). The tumors are often positive for EGFR (Fig 16.17) and p53 protein.

In earlier classifications of anal canal tumors, a grading system was proposed based on two criteria: The presence or absence of squamous cell elements and the degree of differentiation of the transitional cell component (67). However, the current classification advises against grading these tumors since generally the only tissue that is available is a small biopsy, which may not be representative of the entire tumor (1).

Spread of Anal Canal Cancer

Anal canal SCCs spread locally to the lower rectum, to the anal sphincter, and into the ischiorectal fossa. The submucosal layer is very narrow in the anal canal and hence, the mucosa lies very close to the anal sphincter, explaining why anal canal carcinomas often infiltrate this structure. Local perineal invasion with involvement of the posterior vaginal septum, prostate, or bladder affects 15% to 20% of patients. Lateral growth into the ischiorectal fossa may present as an abscess, a fistula, or eventual annular stenosis.

TABLE 16.2 Comparison of the Basaloid Variant of Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Basal Cell Carcinoma | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lesions of the middle and proximal anal canal spread to the mesorectal, superior hemorrhoidal, and inferior mesenteric lymph nodes. Mesorectal node involvement occurs in up to 56% of tumors measuring >4 cm. Metastasis to inguinal lymph nodes occurs in 10% to 25% of tumors and approximately 25% have bilateral lymph node involvement (68). Lower rectal lesions preferentially spread toward the hemorrhoidal lymph nodes and, later, to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes. Up to 44% of lymph node metastases affect lymph nodes measuring <5 mm in diameter, with most positive lymph nodes lying above the peritoneal reflection. Because of the small size of the perianal and perirectal

lymph nodes, many anal canal SCCs are understaged due to failure to find the lymph nodes (69).

lymph nodes, many anal canal SCCs are understaged due to failure to find the lymph nodes (69).

FIG. 16.14. Squamous cell carcinoma with the so-called transitional cell pattern and prominent clear cell features. |

Vascular invasion develops less frequently than lymphatic spread, affecting 10% of patients. Hematogenous spread causes distant metastases in the liver, lung, skin, brain, perineum, or spinal cord. Distant metastases affect up to 10% of patients at the time of diagnosis (62); another 10% to 15% of patients develop metastases during the course of their disease. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging scheme for anal canal carcinomas is presented in Table 16.3.

Prognosis

The prognosis of anal carcinomas depends on the site of origin, tumor size, depth of invasion, extent of local spread, and nodal status (31,62,70,71). Tumor size inversely correlates with prognosis and strongly associates with tumor stage. Lesions that only invade into the submucosa have an excellent prognosis (31). Tumor size is one of the most important prognostic factors, with most tumors measuring <2 cm in diameter being amenable to cure (71). Tumors measuring >8 cm demonstrate a 5-year survival rate of 31% to 47.3%, contrasting with those measuring <8 cm, which have a 75% 5-year survival rate (62). Tumor stage is also important and in part relates to tumor size. Five-year survival rates for early-stage disease are 65% to 71.3% for stage I compared with 23.1% to 33% for stage IV disease (72,73). Patients with distant metastases have a 5-year survival rate of 11%. Patients whose tumors show a squamous histology have a 5-year survival rate of 57.5% compared with 41.3% for adenocarcinoma (73). Patients with inguinal lymph node metastases have a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of <20% (74).

Tumor location is also important. Squamous cell carcinomas arising at the anal margin have a better prognosis than those arising in the anal canal, likely due to the fact that those at the anal margin present as smaller tumors that are more easily cured by local excision (see below). DNA ploidy analysis does not consistently reach independent prognostic significance relative to histologic grade or tumor stage when examined in multivariate analysis (75). However, p53 overexpression may associate with an inferior outcome for patients with anal canal tumors treated with chemoradiation (76).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree