Fig. 18.1

Urogenital septum. Sagittal view demonstrating the urogenital septum (white arrow)

Pelvic Nerve Plexuses

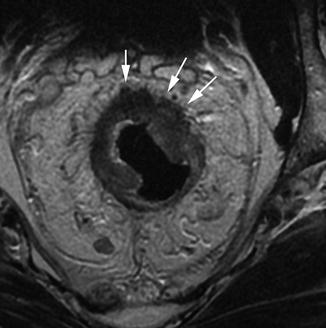

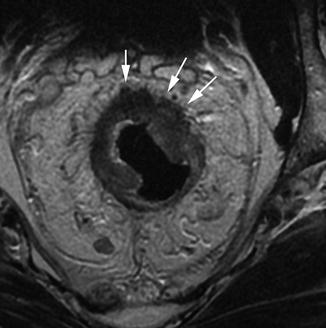

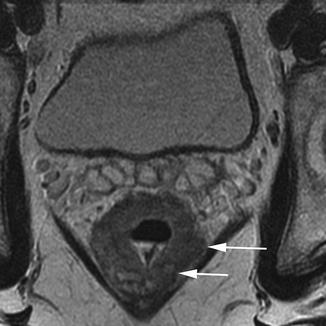

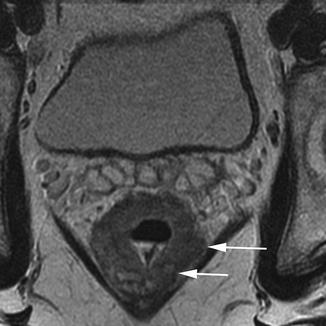

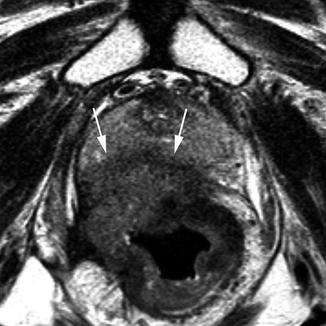

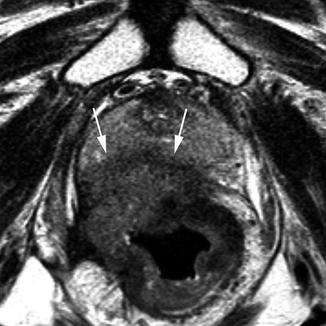

The autonomic nerve supply in the pelvis is important for sexual and urological function and is potentially at risk during rectal cancer surgery. The nerve plexuses can be readily identified on MRI, which allows the relationship to the tumour to be appreciated preoperatively to aid in surgical or neoadjuvant treatment planning. The inferior hypogastric plexus lies sagittally; in the male, the tip of the seminal vesicle marks the midpoint of the plexus, whereas in the female the anterior half of the plexus lies against the upper third of the vagina. The hypogastric plexus lies in a plane just medial to the vessels of the pelvic sidewall and forms a meshwork of interconnecting nerves which can be identified on the coronal (Fig. 18.2) and sagittal (Fig. 18.3) views on MRI.

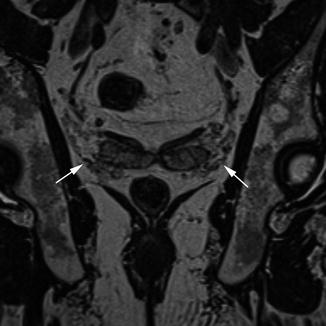

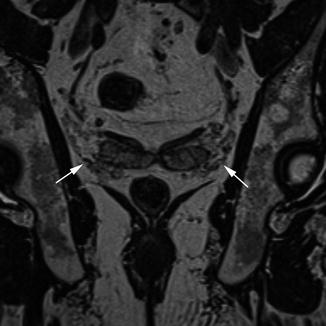

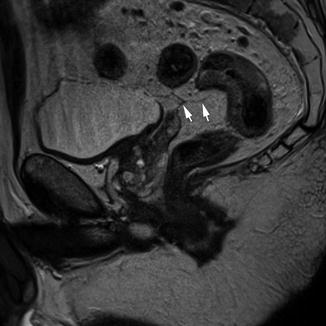

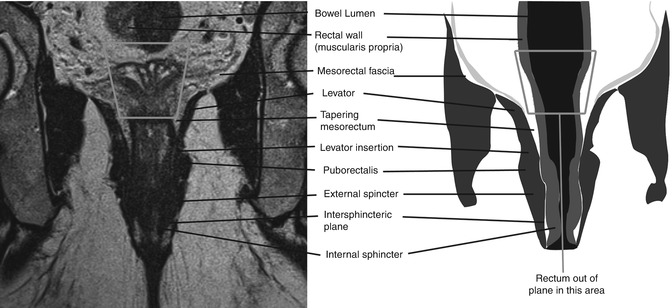

Fig. 18.2

Pelvic nerve plexuses, coronal. Coronal view demonstrating the pelvic nerve plexuses (white arrows)

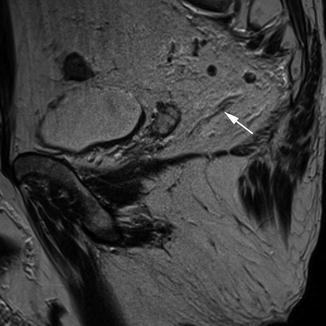

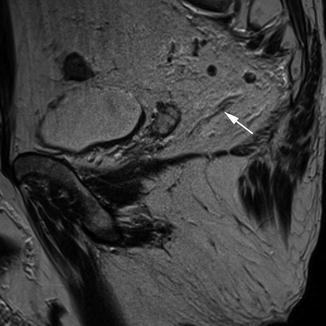

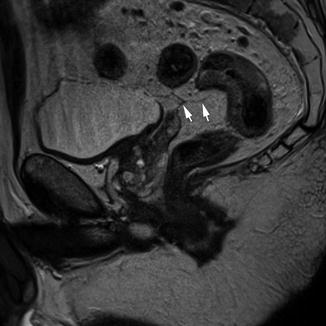

Fig. 18.3

Pelvic nerve plexuses; sagittal. Sagittal view showing the pelvic nerves (white arrow) extending towards the neurovascular bundle of the prostate

Peritoneum

The peritoneum extends from the superior aspect of the bladder posteriorly to the side walls of the pelvis and the anterior surface of the rectum. The peritoneum forms an acute angle in the recess between the bladder in the male and the uterus in female (the rectovesical or rectouterine pouch). This peritoneal reflection is best seen on sagittal MR images, where it can be recognised as a low signal intensity layer extending over the surface of the bladder and continuing to its attachment on the anterior surface of the rectum (Fig. 18.4).

Fig. 18.4

Peritoneal reflection. Sagittal view showing the peritoneal reflection (white arrows)

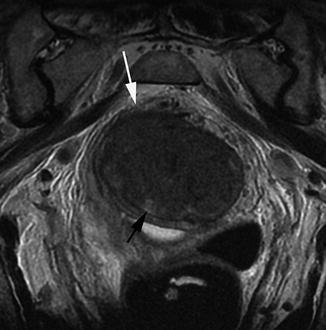

Mesorectum and the Mesorectal Fascia

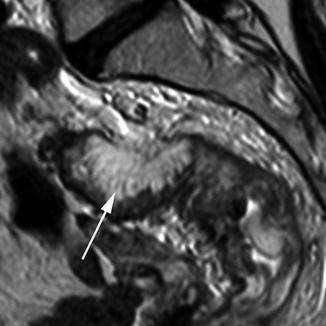

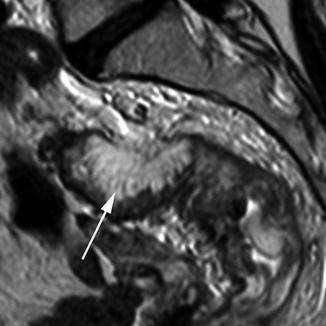

As described previously, the mesorectum is a distinct structure which derives embryologically from the hindgut. This contains the rectum, its associated vessels and draining lymphatics in a package of fatty connective tissue. This package is contained within a fascial layer, the mesorectal fascia, which is derived from the visceral peritoneum. The importance of this fascia in terms of surgical technique and outcome is now well understood [35]. The great strength of MRI compared to other imaging techniques for staging rectal cancer is that this layer can be readily identified on high-resolution T2-weighted images. It is most easily appreciated on axial sequences as a band of low signal intensity surrounding the mesorectum (Fig. 18.5).

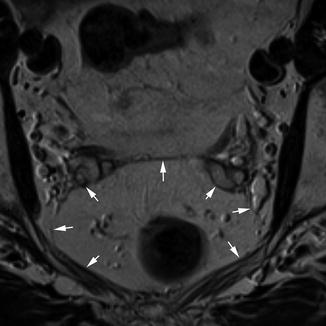

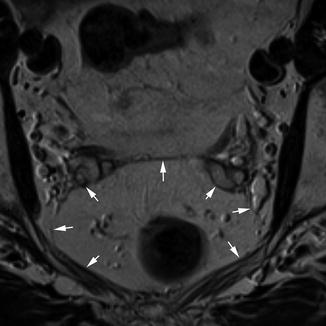

Fig. 18.5

Mesorectal fascia. Transaxial view demonstrating the mesorectal fascia (white arrows)

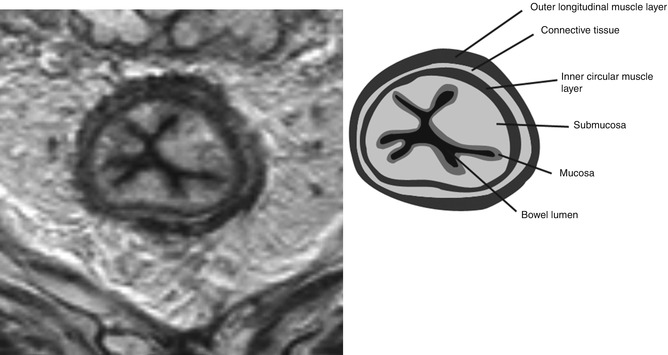

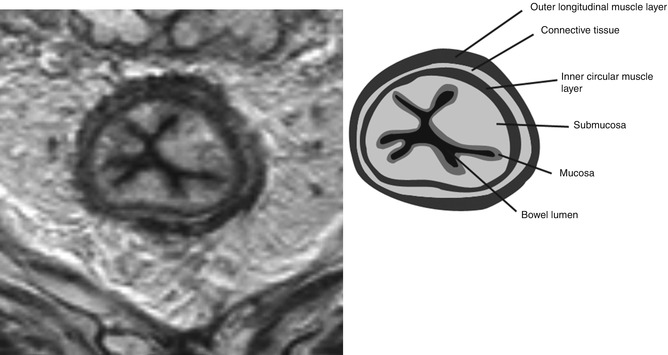

The Bowel Wall

Histologically, the bowel wall can be divided into four layers; the innermost mucosal layer, the muscularis mucosa, the submucosa and the muscularis propria. The muscularis propria can be further subdivided into inner circular and outer longitudinal layers, separated by a thin layer of connective tissue. On MRI, the mucosal layer can be identified as a thin line of low signal intensity overlying the thicker higher signal intensity submucosa. The muscularis mucosa cannot usually be identified as a distinct layer on MRI. The two layers of the muscularis propria can sometimes be identified as two distinct layers (Fig. 18.6); otherwise, it appears as one layer of low signal intensity surrounded by the perirectal tissues which are of high signal intensity due to their high fat content.

Fig. 18.6

Layers of the bowel wall. Transaxial view demonstrating the layers of the bowel wall. This image was acquired following radiotherapy, so the layers of the bowel wall are exaggerated due to tissue oedema

Image Interpretation for MRI Staging of Rectal Cancer

Tumour Morphology

An appreciation of the morphological appearance of rectal cancers, typical patterns of development and spread and common variations is very helpful for understanding the appearances of imaging. Rectal cancers are usually adenocarcinomas, which are thought to arise from adenomas in most cases. These adenomas can be either polypoid or sessile in nature.

Some tumours maintain an exophytic appearance similar to the polypoid adenomas from which they arise. These lesions are often low-grade malignancies even when they form large masses projecting into the bowel lumen [36]. On MRI, these tumours can be seen projecting into the bowel lumen. A preserved layer of high signal intensity representing the submucosal layer is frequently evident, as these are often early-stage tumours. The surface of these tumours often has clefts containing mucous fluid which is high signal on MRI (Fig. 18.7).

Fig. 18.7

Polypoidal tumour. Transaxial view demonstrating a polypoidal tumour entirely filling the rectal lumen. There is invasion through the base of the stalk (white arrow). The surface of the tumour has clefts containing mucin secretion (black arrow)

The most common appearance of adenocarcinomas is annular or semiannular. This appearance can be recognised on MRI as an elevated plaque of intermediate signal intensity projecting into the bowel lumen and extending around the bowel lumen in a U-shape (Fig. 18.8).

Fig. 18.8

Semiannular early T3 tumour. Transaxial view showing a semiannular tumour extending around the anterior three quarters of the bowel wall. There is early invasion into the mesorectal tissues (white arrows), making this an early T3 tumour

As the tumour advances and increases in size, the central portion frequently begins to ulcerate. This area of ulceration overlies the area of deepest invasion through the bowel wall. These features can often be identified on MR imaging.

If the tumour advances further, then it invades through the wall of the bowel into the perirectal tissues. Rectal tumours usually do this with a well-circumscribed border. However, around 25 % of tumours do so with poorly defined borders. In these cases, the malignant cells invade between normal structures, so there is not a distinct leading edge to the tumour. This pattern of spread is associated with a worse prognosis [37]. The former pattern of spread is recognised on MRI as intermediate signal intensity with a broad pushing margin (Fig. 18.8). The latter type is indicated by the presence of fingerlike projections of intermediate signal intensity extending into the perirectal tissues.

Some tumours have preponderance for ulceration at a relatively small size. These tumours may cause diffuse thinning of the bowel wall which can make identification of the layers of the rectum more difficult. This can also make determining the degree of extramural spread more difficult than in other morphological types.

Mucinous tumours are defined as tumours containing more than 75 % mucin [38]. Although this morphological subtype accounts for only 10 % of tumours, they are important because they are associated with a poorer prognosis. This is thought to be due to the fact that they have a poorly defined margin and are often advanced at the time of presentation. They may also spread intramurally which is rare in other morphological subtypes of rectal tumours, unlike upper gastrointestinal tumours. This form of tumour can be recognised on MRI by their very high signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging. As these tumours are often diffusely infiltrating, anatomical layers may be preserved by expanded by high signal intensity (Fig. 18.9).

Fig. 18.9

Mucinous tumour. Sagittal view showing a mucinous tumour (white arrow). The invasive border (posteriorly) is diffusely infiltrating

T Stage

In histological terms, T1 tumours have invaded into, but not through, the submucosa. On MRI, part of the high signal intensity submucosa is sometimes still preserved. In this case, it has a high positive predictive value for a T1 tumour.

Unfortunately, loss of the high signal submucosal layer does not necessarily allow differentiation between T1 and T2 tumours. This is because microscopic infiltration of the tumour into the muscular layer (T2) is indistinguishable on MRI from complete replacement of the submucosa without infiltration into the muscular layer (T1). Similarly, it is difficult to differentiate between a tumour occupying the whole thickness of the bowel wall without invasion through the wall (T2) from a tumour with very early invasion into the perirectal tissues (T3). The distinction between of T2 and early T3 tumours (T3a <1 mm invasion into perirectal fat or T3b 1–5 mm invasion into perirectal fat) is of less prognostic significance than the distinction between early and advanced T3 tumours (T3c 5–15 mm extramural invasion, T3d >15 mm extramural invasion).

T3 tumours show invasion into the perirectal tissues. This can be identified on MRI as a broad-based pushing or nodular margin of intermediate signal intensity moving beyond the bowel wall into the perirectal fat (Figs. 18.8 and 18.10).

Fig. 18.10

Poor prognosis T3 tumour. Transaxial view showing a poor prognosis T3 tumour. The mesorectal fascia is threatened posterolaterally on the left side (white arrows)

T4 tumours are defined as invading into an adjacent organ or having perforated the peritoneum (Fig. 18.11). It is important to look carefully for evidence of these features in advanced tumours. Structures at risk will be dependent on the site of the tumour and the direction of the leading margin of the tumour. In the upper and mid rectum, in the anterior direction the uterus or bladder is at risk, as well as the peritoneal surface. Laterally, the tumour may invade into the pelvic sidewall, and in the posterior direction, the sacrum may be involved by an advanced tumour. Tumours in the lower third of the rectum place will invade the structures of the pelvic floor if they become locally advanced. The prostate, seminal vesicles or vagina may be involved anterior to the rectum, the levator muscles laterally, and the sacrum or coccyx in the posterior direction. The MRI T-staging system for rectal tumours is summarised in Table 18.1.

Fig. 18.11

T4 tumour. Transaxial view showing a T4 tumour with invasion into the prostate anteriorly (white arrows)

Table 18.1

T-staging rectal tumours using MRI

T stage | Definition | MRI appearances |

|---|---|---|

Tx | Primary tumour cannot be assessed | |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumour | |

T1 | Tumour invades submucosa | Tumour signal intensity within submucosal layer or replacement of submucosal layer by tumour signal intensity but not extending into muscularis propria |

T2 | Tumour invades but confined to muscularis propria | Tumour signal intensity within muscularis propria or tumour signal intensity replaces muscularis propria but does not extend into mesorectal fat |

T3 | Tumour invades through muscularis propria into subserosa (mesorectum) | Broad-based bulge or nodular projection (but not fine speculation) of tumour signal intensity beyond outer muscular layer |

T3a | Tumour extends <1 mm beyond muscularis propria | |

T3b | Tumour extends 1–5 mm beyond muscularis propria | |

T3c | Tumour extends 5–15 mm beyond muscularis propria | |

T3d | Tumour extends >15 mm beyond muscularis propria | |

T4 | Tumour invades other organs or penetrates peritoneum | Extension of tumour signal intensity into adjacent organ OR extension of tumour signal intensity through peritoneal reflection |

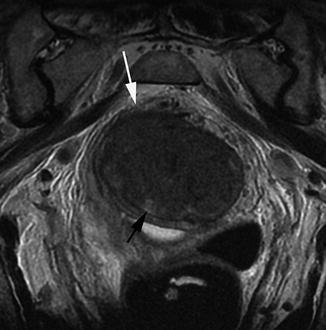

Circumferential Resection Margin

The circumferential resection margin (CRM) involvement is the most important factor in determining local recurrence in rectal cancer [40]. It is therefore important to identify those patients with a potentially positive circumferential resection margin, which is defined as tumour within 1 mm of the mesorectal fascia [41]. The distance from the closest tumour margin to the mesorectal fascia should be measured and recorded (Fig. 18.12). Lymph nodes considered to be metastatic, tumour deposits or extramural vascular invasion (EMVI) lying within 1 mm of the CRM also threaten the margin and should be recorded separately.

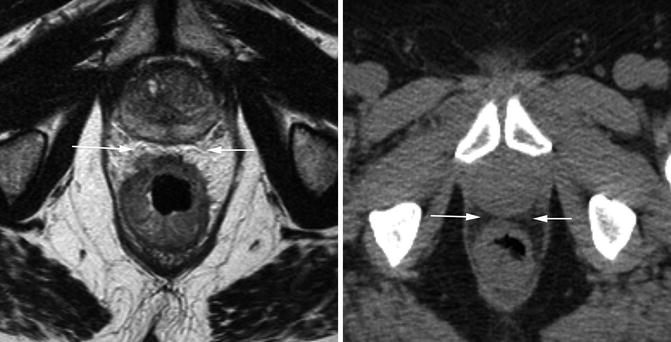

Fig. 18.12

CT and MRI showing tumour distance to mesorectal fascia. Transaxial views through a tumour at the same level on MRI (left) and CT (right). The anterior margin (white arrows) appears involved on CT, but a clear margin can be seen on MRI

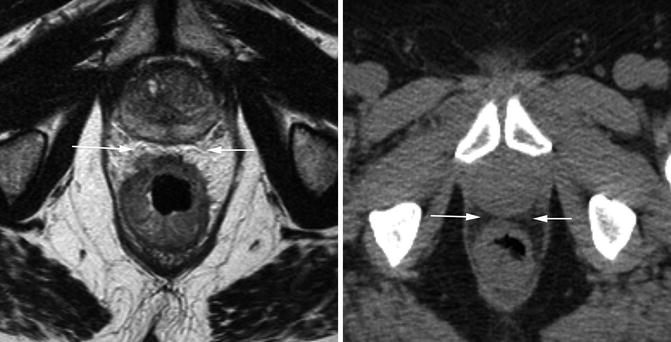

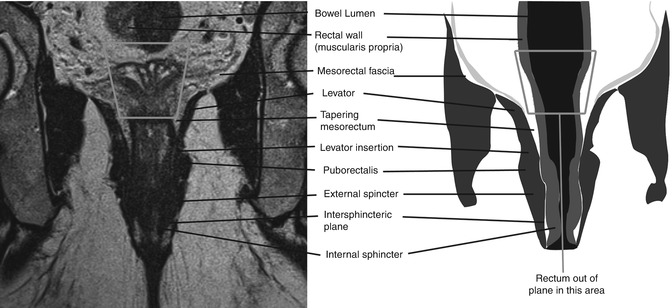

Low rectal tumours require special consideration, as the anatomy in this area is different to the rest of the rectum, and outcomes for patients treated with abdominoperineal excision (APE) are worse in terms of margin involvement and local recurrence than those treated by anterior resection (AR) [42]. The mesorectum at this level tapers in a V shape down to top of the sphincter complex, just deep (or superior) to the levator muscles. The internal anal sphincter is formed from the circular muscle layer of the muscularis propria. At the top of the sphincter, muscle fibres from the puborectalis sling join with the fibres of the outer longitudinal muscle layer of the muscularis propria to form a thin muscular layer between the internal and external sphincters. The external sphincter consists of voluntary muscle fibres which are continuous superiorly with the levator ani muscles (Fig. 18.13).

Fig. 18.13

MRI showing anatomy of the sphincter complex. Coronal image and accompanying diagram demonstrating the anatomy of the sphincter complex as seen on MRI. Note that the rectum goes out of plane and therefore is not seen in the middle portion of the image (grey box)

Tumours 1 mm or more from the mesorectal fascia may be safely treated by low anterior resection. The continuation of this plane is the intersphincteric plane, and tumours 1 mm or more from the outer border of the internal sphincter may be safely excised by a conventional intersphincteric APE [43]. However, if the tumour extends into the levator muscles or the intersphincteric plane, then the patient would require downstaging long-course chemoradiotherapy or an extra-levator APE as described by Holm et al. [44]. Tumours with extensive local invasion into adjacent structures may require pelvic exenteration. Table 18.2 shows a scheme described by Brown et al. for staging low rectal tumours, with appropriate surgical management.

Table 18.2

Staging and operative management of low rectal cancers

Level | Tumour height | Tumour depth | Operative plane |

|---|---|---|---|

1 | Between levator origin and puborectalis sling | Confined to muscularis propria | LAR/intersphincteric APE |

Beyond muscularis propria, >1 mm from mesorectal fascia/levator muscle | LAR/intersphincteric APE | ||

Within 1 mm of mesorectal fascia/levator muscle | Extra-levator APE | ||

Extending into levator muscle | Extra-levator APE | ||

2 | Tumour at or below puborectalis sling | Submucosa/partial thickness of muscularis propria | Intersphincteric APE |

Into the intersphincteric plane

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|