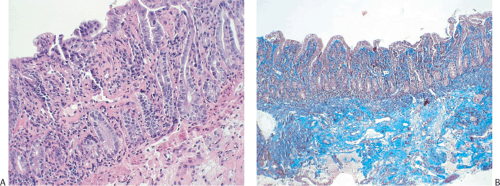

Microvillous Inclusion Disease

Microvillous inclusion disease (MID) occurs worldwide in infants from varying ethnic backgrounds. The disease may have a familial component as it sometimes occurs in multiple siblings (543). A genetic etiology is further supported by the observation that the disease appears to cluster in infants of Navajo descent (544). The mechanism by which microvillous inclusion disease develops is unknown. The underlying defect is thought to represent a genetic alteration that leads to abnormal trafficking of membrane proteins to the apical surface of differentiated epithelial cells (545).

Infants with microvillous inclusion disease present with severe, watery diarrhea. In some cases, the diarrhea can be so watery that it can be mistaken for urine. The volume of stool output in this disease may exceed that seen in association

with cholera (545). As a result, affected infants die of dehydration unless adequate fluid replacement is provided.

with cholera (545). As a result, affected infants die of dehydration unless adequate fluid replacement is provided.

Both congenital and late-onset forms of MID exist. Patients with late-onset disease have a better prognosis than those with congenital disease. Patients with the congenital form of the disease present with protracted diarrhea from birth and develop mildly hyperplastic villous atrophy (546). The disorder is worsened by oral feeding. The prognosis is extremely poor in infants because they depend completely on total parenteral nutrition. They usually die before the age of 18 months from liver failure, sepsis, and dehydration. All patients experience decreased absorption of water, electrolytes, and nutrients. The only effective therapy is small intestinal or multivisceral transplantation (547).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree