Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) account for less than 5% of all pancreatic cancers and have an estimated overall incidence of 5 cases per 1 million population annually. In recent years the diagnosed incidence of neuroendocrine tumors has been increasing, probably due at least in part to improved detection and diagnosis. PNETs are best known for their association with characteristic syndromes of hormone hypersecretion. Such symptoms can often be effectively controlled with medical therapy, and when tumors are localized they can be successfully resected. However, the majority of PNETs are clinically silent, presenting at a more advanced clinical stage. Treatment options for patients with advanced PNET have previously been limited. Recently, new biologically targeted therapies have been approved for these tumors and offer improved treatment opportunities for patients with this disease.

Causes and Genetics

PNETs, also termed islet cell tumors , were originally thought to arise from the hormone-producing islet cells of the pancreas. Recent studies have suggested that PNETs may, in fact, arise from ductal progenitor cells, which are putative embryonic and adult pancreatic stem cells. A minority of PNETs are associated with inherited genetic syndromes, including multiple endocrine neoplasia type I (MEN1), von Hippel-Lindau disease, von Recklinghausen disease/neurofibromatosis, and the tuberous sclerosis complex. PNETs are present in the majority of MEN1 patients but are less commonly associated with the other inherited genetic syndromes.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Approximately 70% of PNETs are not associated with symptoms of hormone hypersecretion and instead present with vague abdominal complaints related to mass effect. Much attention has been focused on the potential use of secreted biomarkers for the detection and diagnosis of such tumors. Chromogranin A is a ubiquitous component of dense-core granules in all neuroendocrine cells and is cosecreted with neurohumoral products. Although chromogranin A may be a useful adjunct to other diagnostic modalities, most studies suggest it is not sufficiently sensitive or specific to serve as an independent biomarker. In one study, elevated chromogranin A had a sensitivity of 67.9% and specificity of 85.7% in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. In those patients who do present with symptoms of hormone hypersecretion, symptoms depend in large part on the specific hormone secreted. Characteristic syndromes are summarized in Table 1 and are described further in the following sections.

| Tumor | Symptoms or Signs | Medical Management |

|---|---|---|

| Insulinoma | Hypoglycemia resulting in intermittent confusion, sweating, weakness, nausea. Loss of consciousness may occur in severe cases. | Frequent small meals, diazoxide, dextrose infusions, everolimus |

| Glucagonoma | Rash (necrotizing migratory erythema), cachexia, diabetes, deep venous thrombosis. | Somatostatin analogs |

| VIPoma, Verner-Morrison Syndrome, WDHA Syndrome | Profound secretory diarrhea, electrolyte disturbances. | Somatostatin analogs |

| Gastrinoma, Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome | Acid hypersecretion resulting in refractory peptic ulcer disease, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. | Proton pump inhibitors, somatostatin analogs |

| Nonfunctioning | May be first diagnosed because of mass effect. | Therapy for tumor control in patients with unresectable disease |

Insulinoma

Insulinomas were first described by Whipple and Frantz in 1935 as causing a syndrome of hypoglycemia and neuroglycopenic or sympathetic symptoms that resolve with feeding. When this triad is identified, serum assessment of insulin, proinsulin, C peptide, and glucose are generally used to confirm an endogenous hyperinsulinemic state. Absence of ketosis or sulfonylurea metabolites in the blood or urine is another criterion used for diagnosis of insulinoma. For many patients, frequent small meals can normalize the blood glucose sufficiently to relieve symptoms. For others, continuous infusions of dextrose can be used. Diazoxide, a nondiuretic antihypertensive seldom used for that indication, has also been used to normalize blood glucose levels. More recent reports have suggested that treatment with the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus is highly effective in normalizing glucose levels in patients with symptomatic insulinoma. However, over 90% of these tumors are small, solitary, and successfully treated with surgical resection.

Gastrinoma

Gastrinomas result in a syndrome of hypergastrinemia and refractory peptic ulcer disease originally described by Zollinger and Ellison. Patients typically present with gastroesophageal reflux, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and multiple duodenal ulcers ( Fig. 1 ). The diagnosis can be confirmed with elevated fasting gastrin levels, which can be stimulated to supraphysiologic levels in a secretin stimulation test. Importantly, hypercalcemia due to primary hyperparathyroidism in MEN1 patients may independently increase gastrin secretion and stomach acidification in the absence of true gastrinoma. Symptoms of gastrinoma can be controlled with proton pump inhibitors, which block the effect of the gastrin without reducing its serum concentration or altering the tumor biology. Treatment with somatostatin analogs is also commonly used to suppress gastrin secretion and in some cases to control tumor growth.

Gastrinomas may present not only in the pancreas but also in extrapancreatic locations within the “gastrinoma triangle.” Localizing gastrinomas can be challenging and not uncommonly requires careful imaging with magnetic resonance imaging, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, or endoscopic ultrasound. Although advances in somatostatin receptor scintigraphy have improved preoperative localization of PNETs, 30% of tumors are still undetected, including over 60% of tumors smaller than 1 cm. Empiric surgery with duodenotomy has therefore been considered in selected hypergastrinemic patients suspected of having gastrinoma.

Glucagonoma

Glucagonomas are associated with the development of migratory necrolytic erythema (dermatitis), diabetes, and an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis. Demonstration of elevated plasma glucagon levels confirms the presence of glucagonoma syndrome. Glucagonomas frequently present as large tumors and at a more advanced stage than other secretory neuroendocrine tumors. Surgical resection is performed when feasible; otherwise, treatment with somatostatin analogs is used to control symptoms.

Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide Tumors (VIPomas)

Patients with tumors that secrete vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIPomas) present with a syndrome of massive (frequently greater than 3 liters daily) secretory diarrhea associated with hypokalemia in the absence of gastric ulceration. This syndrome, caused by excess secretion of vasoactive intestinal peptide, was originally described by Verner and Morrison and has also been described as pancreatic cholera. Elevated levels of vasoactive intestinal peptide in the setting of a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor are diagnostic of this syndrome. The secretory symptoms associated with VIPoma are highly responsive to somatostatin analogs.

Other PNETs

PNETs have also been reported to secrete somatostatin, adrenocorticotrophic hormone producing Cushing syndrome, growth hormone-releasing factor producing acromegaly, and various other hormones including erythropoietin and luteinizing hormone.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Approximately 70% of PNETs are not associated with symptoms of hormone hypersecretion and instead present with vague abdominal complaints related to mass effect. Much attention has been focused on the potential use of secreted biomarkers for the detection and diagnosis of such tumors. Chromogranin A is a ubiquitous component of dense-core granules in all neuroendocrine cells and is cosecreted with neurohumoral products. Although chromogranin A may be a useful adjunct to other diagnostic modalities, most studies suggest it is not sufficiently sensitive or specific to serve as an independent biomarker. In one study, elevated chromogranin A had a sensitivity of 67.9% and specificity of 85.7% in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. In those patients who do present with symptoms of hormone hypersecretion, symptoms depend in large part on the specific hormone secreted. Characteristic syndromes are summarized in Table 1 and are described further in the following sections.

| Tumor | Symptoms or Signs | Medical Management |

|---|---|---|

| Insulinoma | Hypoglycemia resulting in intermittent confusion, sweating, weakness, nausea. Loss of consciousness may occur in severe cases. | Frequent small meals, diazoxide, dextrose infusions, everolimus |

| Glucagonoma | Rash (necrotizing migratory erythema), cachexia, diabetes, deep venous thrombosis. | Somatostatin analogs |

| VIPoma, Verner-Morrison Syndrome, WDHA Syndrome | Profound secretory diarrhea, electrolyte disturbances. | Somatostatin analogs |

| Gastrinoma, Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome | Acid hypersecretion resulting in refractory peptic ulcer disease, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. | Proton pump inhibitors, somatostatin analogs |

| Nonfunctioning | May be first diagnosed because of mass effect. | Therapy for tumor control in patients with unresectable disease |

Insulinoma

Insulinomas were first described by Whipple and Frantz in 1935 as causing a syndrome of hypoglycemia and neuroglycopenic or sympathetic symptoms that resolve with feeding. When this triad is identified, serum assessment of insulin, proinsulin, C peptide, and glucose are generally used to confirm an endogenous hyperinsulinemic state. Absence of ketosis or sulfonylurea metabolites in the blood or urine is another criterion used for diagnosis of insulinoma. For many patients, frequent small meals can normalize the blood glucose sufficiently to relieve symptoms. For others, continuous infusions of dextrose can be used. Diazoxide, a nondiuretic antihypertensive seldom used for that indication, has also been used to normalize blood glucose levels. More recent reports have suggested that treatment with the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus is highly effective in normalizing glucose levels in patients with symptomatic insulinoma. However, over 90% of these tumors are small, solitary, and successfully treated with surgical resection.

Gastrinoma

Gastrinomas result in a syndrome of hypergastrinemia and refractory peptic ulcer disease originally described by Zollinger and Ellison. Patients typically present with gastroesophageal reflux, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and multiple duodenal ulcers ( Fig. 1 ). The diagnosis can be confirmed with elevated fasting gastrin levels, which can be stimulated to supraphysiologic levels in a secretin stimulation test. Importantly, hypercalcemia due to primary hyperparathyroidism in MEN1 patients may independently increase gastrin secretion and stomach acidification in the absence of true gastrinoma. Symptoms of gastrinoma can be controlled with proton pump inhibitors, which block the effect of the gastrin without reducing its serum concentration or altering the tumor biology. Treatment with somatostatin analogs is also commonly used to suppress gastrin secretion and in some cases to control tumor growth.

Gastrinomas may present not only in the pancreas but also in extrapancreatic locations within the “gastrinoma triangle.” Localizing gastrinomas can be challenging and not uncommonly requires careful imaging with magnetic resonance imaging, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, or endoscopic ultrasound. Although advances in somatostatin receptor scintigraphy have improved preoperative localization of PNETs, 30% of tumors are still undetected, including over 60% of tumors smaller than 1 cm. Empiric surgery with duodenotomy has therefore been considered in selected hypergastrinemic patients suspected of having gastrinoma.

Glucagonoma

Glucagonomas are associated with the development of migratory necrolytic erythema (dermatitis), diabetes, and an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis. Demonstration of elevated plasma glucagon levels confirms the presence of glucagonoma syndrome. Glucagonomas frequently present as large tumors and at a more advanced stage than other secretory neuroendocrine tumors. Surgical resection is performed when feasible; otherwise, treatment with somatostatin analogs is used to control symptoms.

Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide Tumors (VIPomas)

Patients with tumors that secrete vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIPomas) present with a syndrome of massive (frequently greater than 3 liters daily) secretory diarrhea associated with hypokalemia in the absence of gastric ulceration. This syndrome, caused by excess secretion of vasoactive intestinal peptide, was originally described by Verner and Morrison and has also been described as pancreatic cholera. Elevated levels of vasoactive intestinal peptide in the setting of a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor are diagnostic of this syndrome. The secretory symptoms associated with VIPoma are highly responsive to somatostatin analogs.

Other PNETs

PNETs have also been reported to secrete somatostatin, adrenocorticotrophic hormone producing Cushing syndrome, growth hormone-releasing factor producing acromegaly, and various other hormones including erythropoietin and luteinizing hormone.

Imaging Modalities

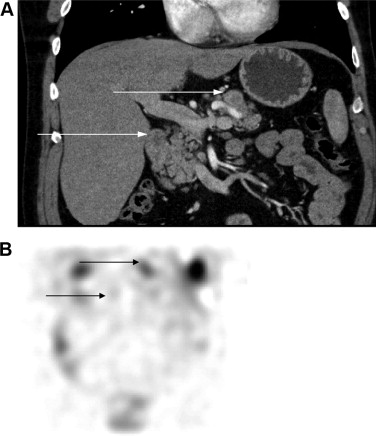

Detection of both primary lesions and metastases has been significantly improved with the development of increasingly sensitive imaging techniques. Because of its speed and availability, computed tomography (CT) is typically the initial imaging technique used to localize the primary tumor when a hormonal syndrome is identified. Nonfunctioning tumors are most commonly identified incidentally on CT while evaluating mass-related symptoms. Given the vascularity of these lesions, intravenous contrast and multiphasic imaging (including arterial and portal venous phases) is usually recommended. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium is an alternative imaging modality with a modest increase in sensitivity compared with CT. Use of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy with an indium-111–labeled somatostatin analog ([ 111 In-DTPA 0 ]octreotide) provides a further imaging modality with relatively high sensitivity and specificity for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors ( Fig. 2 ).

Traditional imaging techniques are nevertheless often insufficient for localization of all PNETs, especially those smaller than 1 cm in diameter. Endoscopic ultrasound may be more sensitive for detection, particularly for these smaller lesions, and it also provides the potential opportunity to perform a diagnostic biopsy. Recent studies have reported that the use of echogenic contrast can improve sensitivity and specificity for both exocrine carcinoma and neuroendocrine tumors in lesions smaller than 2 cm. When used in conjunction with fine-needle aspiration, this technique’s sensitivity for malignancy is 100%, improved from 92% when contrast was not used.

Staging, Grade, and Prognosis

Several organizations, including the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) have proposed staging systems for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors using the commonly accepted TNM (tumor status-nodal status-metastatic status) notation. These two systems differ slightly; for example, the ENETS system incorporates tumor diameter in its assessment of T stage, whereas the AJCC system incorporates factors determining tumor resectability. Both systems have been clinically validated and are nearly identical in their definitions of stage IV disease.

Stage has a major impact on prognosis. Patients with early-stage, surgically resectable disease generally have high cure rates. The modified ENETS-TNM system predicts a 5-year survival of 100% for stage I disease (tumors <4 cm, restricted to the pancreas), 93% for stage II disease (tumors >4 cm but still restricted to the pancreas), 65% for stage III disease (tumors invading adjacent structures or with positive lymph nodes), and 35% for stage IV (metastatic) disease. Survival estimates for patients with advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors vary. In the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, for example, the median survival duration for patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors was only 24 months. Survival estimates in institutional series are more encouraging, with some estimates for median survival approaching 6 years.

A number of histologic classification systems have been proposed to subclassify neuroendocrine tumors. Despite some differences, all commonly used classification systems reflect the basic observation that neuroendocrine tumors have a spectrum of malignancy ranging from more indolent, well-differentiated tumors to far more aggressive poorly differentiated ones ( Table 2 ). As a general rule, tumors with a high grade (grade 3), a mitotic count greater than 20/10 high-powered fields, or a Ki-67 proliferation index of more than 20% represent highly aggressive malignancies with a clinical behavior that differs markedly from more well-differentiated tumors.