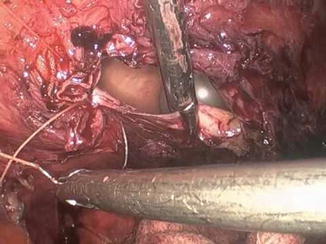

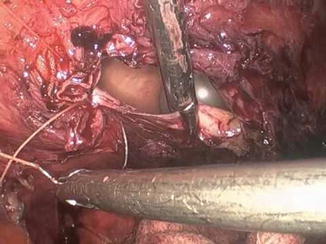

Fig. 22.1

Hasson or open entry technique

22.3 Vascular Complications

Vascular injuries are one of the most serious and potentially catastrophic complications of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. Fortunately, the incidence of major vascular injuries is uncommon, occurring in 0.01–1 % of cases [1, 2, 4–6]. However, mortality can be as high as 9–23 % [2, 6].

22.3.1 Major Vascular Injuries

Major vessel injuries are almost five times as common during Veress needle insertion or placement of the primary trocar than during the laparoscopic operation itself [2]. The majority of major vascular injuries are arterial, with aortic and right common iliac artery injuries being the most frequent (Table 22.1). The most commonly injured venous structure is the vena cava [6, 7]. When gaining access to the peritoneal cavity using closed entry via the umbilicus, one must keep in mind the anatomic relationship of the umbilicus to the underlying retroperitoneal vessels. In non-obese patients (BMI <30 mg/m2), the aortic bifurcation lies at or slightly caudal to the level of the umbilicus. At a 45-degree angle, the average abdominal wall thickness measures 2–3 cm, and at a 90-degree angle, the vessels are usually 6–10 cm from the skin but may be as close as 2 cm to the skin. Thus, inserting instruments through the base of the umbilicus at a 45-degree angle minimizes the risk of injury while still maintaining a high probability of successful entry. In obese women (BMI ≥30 kg/m2), the aortic bifurcation is almost always cephalad to the level of the umbilicus. At a 45-degree angle, the average abdominal wall thickness in these patients is 11 cm, and at a 90-degree angle, the distance between the skin and the retroperitoneal vessels is greater than 13 cm. In obese patients, it is recommended that instruments be inserted through the base of the umbilicus at a 90-degree angle in order to maximize successful entry; injury to the aorta and vena cava are less likely to occur because they are further away. The angle of the surgical table must also be taken into account, since patients are often in the Trendelenburg position during laparoscopy. If the patient’s feet are elevated 30° prior to instrument insertion, placing a trocar or Veress needle at a 45-degree angle to the horizontal will result in inserting the instrument at a 75-degree angle, which could result in serious consequences [7].

Many surgeons prefer open laparoscopy for placement of the primary port. Although a recent systematic review of randomized controlled trials looking at laparoscopic entry techniques reported that these studies were underpowered to detect differences in the incidence of vascular injury between various modalities [5], past literature reviews have reported vascular injuries to be a very rare complication of open entry [1, 2, 7]. All trocar types have been reported as associated with major vascular injuries; therefore technique seems to be a factor.

Major injury to the retroperitoneal vessels can also occur during secondary port placement. Lateral trocars are routinely placed 8 cm lateral to the midline and 5 cm superior to the mid-pubic symphysis to avoid injury to the vessels of the anterior abdominal wall. However, the external iliac vessels often lie directly deep to this specific location. Lateral trocars should thus be placed under direct visualization in a slow, controlled manner, along an axis perpendicular to the anterior abdominal wall. Using excessive force should be avoided, as an unexpected loss of resistance may drive the trocar directly into viscera or a major vessel.

Vascular injuries tend to be relatively easy to diagnose intraoperatively, and because of the potentially high risk of mortality, rapid recognition is imperative. Injuries involving the Veress needle or trocar can be recognized by the return of frank blood through the needle or trocar sheath. Lacerations to major retroperitoneal vessels will almost always result in brisk bleeding or an expanding hematoma. Major vascular injury should be considered if the patient becomes hemodynamically unstable during surgery. Sometimes vascular injuries can be hidden temporarily behind the omentum or retroperitoneally.

When a major vessel injury is discovered, the site should be immediately tamponaded with a blunt laparoscopic instrument. If the injury occurred as a result of a Veress needle or trocar puncture and it is still directly in the vessel, it should not be removed. Communication is key to patient outcome and survival. Anesthesia must be promptly notified, as well as vascular surgery, if available. Blood products and appropriate instruments should be called for. If the injury was from a secondary trocar or occurred during the procedure and the bleeding is controlled with pressure, the intraperitoneal cavity may remain insufflated while emergency resources are being established. Some vascular injuries can be repaired laparoscopically in the hands of experienced vascular or gynecologic oncology surgeons, but in most cases, a laparotomy will be required.

Uncontrolled bleeding warrants emergency laparotomy via midline vertical incision (from the xyphoid to the suprapubic region). Upon entry into the abdominal cavity, aortic compression should be performed immediately. Proximal and distal control of the bleeding vessel can be obtained once the site of injury is identified. Small arterial lacerations may be successfully sutured, while large arterial injuries and injuries to the great veins often require graft repair. With continued uncontrolled hemorrhage, the abdomen can be packed with laparotomy sponges while the situation is reassessed.

Small vascular injuries may not always be apparent during surgery. If a patient’s blood count is inexplicably low, serial laboratory results should be obtained. Continued decrease in hematocrit level or signs of hemodynamic instability should be considered as secondary to ongoing hemorrhage until proven otherwise.

Table 22.1

Site and number of vascular injuries

Site | Number of vascular injuries |

|---|---|

Right iliac artery | 14 |

Right iliac vein | 12 |

Left iliac artery | 3 |

Left iliac vein | 9 |

Aorta | 4 |

Vena cava | 2 |

Mesenteric | 2 |

Interior epigastrica | 2 |

Other | 1 |

Total injuries | 49 |

22.3.2 Vascular Injuries to the Anterior Abdominal Wall

Major vascular injury to the anterior abdominal wall usually occurs during lateral trocar placement. The incidence of abdominal wall bleeding is 0.5 %, and in one study is less frequent with the use of blunt versus sharp-cutting trocars [2]. The inferior epigastric artery is the most commonly injured vessel. It branches off of the external iliac artery laterally, pierces the transversalis fascia, and courses medially and then superiorly in the rectus abdominis muscle, where it eventually anastomoses with the superior epigastric artery. Secondary trocars should be placed lateral to the rectus sheath.

The peritoneum covering the inferior epigastric vessels, also known as the lateral umbilical ligaments, can usually be identified as smooth ridges along the inner surface of the anterior abdominal wall, traveling superiorly and medially from the left lower quadrant and right lower quadrant toward the umbilicus. Thus, inserting the trocars under direct visualization after proper identification of these peritoneal folds can help reduce the risk of injury.

An injury to the inferior epigastric vessel can be diagnosed by bleeding from the trocar site into the abdomen or local hematoma formation. Although there is a potential for significant bleeding, these injuries can be managed in several ways. If the trocar is removed and the vessel has not retracted into the abdominal wall, bipolar coagulation may be used to achieve hemostasis. A Foley catheter can also be inserted through the trocar site and the balloon inflated to tamponade the bleeding vessel. Alternatively, if the surgeon desires to continue the surgery, the trocar can be left in place and the vessels ligated with suture cephalad and caudad to the injury. This can be performed with a large curved needle or, if the patient is obese, laparoscopically using a Keith needle that is passed through the entire thickness of the anterior abdominal wall.

In some instances, an injury to an anterior abdominal wall vessel may not be identified immediately. Severe pain around the trocar site, ecchymosis, and a palpable mass are signs of a rectus sheath hematoma. If the hematoma stays stable in size, expectant management is appropriate. However, if it continues to expand, or if there is a significant drop in the patient’s hematocrit, exploration of the wound and ligation of the bleeding vessel are necessary [5].

22.4 Urinary Tract Injuries

Urinary tract injuries complicate 0.03–1.7 % of laparoscopic gynecologic surgeries [1, 2, 8]. Bladder injuries, which are more common than ureteral injuries, are up to 15 times more likely to be diagnosed intraoperatively compared with ureteral lesions [1, 8, 9]. Given the potential for significantly increased morbidity with delayed diagnosis, such as peritonitis, compromised renal function, or fistula formation, it is important for the gynecologic surgeon to be familiar with the risks of urinary tract injuries, strategies for prevention, diagnostic methods, and principles of treatment.

22.4.1 Urinary Bladder Injuries

The most common type of bladder injury is perforation [1, 2, 8, 9]. Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomies have the highest incidence of bladder injuries [8, 9]. Bladder injuries may occur in several ways. Puncture from a Veress needle generally causes a small perforation, whereas trocar injuries may result in larger lacerations. Placement of a midline suprapubic trocar can cause significant damage, especially when the bladder has not been decompressed. In addition, thermal injuries may occur when using electrocautery to dissect the bladder off of the lower uterine segment during a hysterectomy. Thus, it is important to insert a Foley catheter prior to making an abdominal incision. Secondary trocar placement should be performed under direct visualization, and consideration should be given to lateral trocar placement if a suprapubic port is not absolutely necessary. If tissue planes are unclear when dissecting the bladder from the lower uterine segment, especially in cases of endometriosis or severe adhesive disease, it is important to use sharp dissection. Blunt dissection can cause indiscriminate tearing at the site of least resistance, which may result in injury [9]. Retrograde filling of the bladder with saline or water can also help delineate its boundaries when anatomy is significantly distorted.

Signs of bladder compromise can be obvious, such as seeing or palpating the bulb of the Foley catheter in the surgical field or witnessing frank extravasation of urine. Pneumaturia or air in the Foley bag is also indicative of a bladder injury. While transient hematuria may result from manipulation or irritation of the bladder mucosa, persistent bloody urine should prompt a thorough investigation. If an injury is suspected but not apparent, it is helpful to backfill the bladder with dilute indigo carmine or methylene blue and watch for leakage of dye. This can also help identify areas that may have been weakened from dissection, where only the mucosa is left intact. Thermal injuries are often difficult to detect and may not be apparent until several days later. Signs or symptoms of concern for delayed diagnosis of bladder injury include abdominal pain, distention, ileus, ascites, and peritonitis, with or without leukocytosis.

Injuries diagnosed intraoperatively should be repaired prior to the completion of surgery. Expectant management is appropriate for minimal defects in the bladder dome, such as those created by a Veress needle. Defects less than 1 cm in diameter may be closed surgically or managed by prolonged decompression with a Foley catheter. Cystotomies 1 cm or larger are usually repaired with a simple two-layer closure using delayed absorbable suture, bringing together the mucosa and muscularis first and then the serosa for reinforcement (Fig. 22.2). The suture line should be tested for a watertight seal by instilling 300 mL of dye into the bladder and looking for leakage. A Foley catheter should be left in place for 4–14 days, depending on the size and location of the defect. Larger injuries and those located at the trigone may require more time to heal. Prior to removal of the catheter, a cystogram is should be obtained to ensure that appropriate epithelialization has occurred.

If a bladder injury is suspected after surgery, a cystogram can be performed for focused evaluation. Symptoms can be varied and can include nausea, vomiting, malaise, abdominal pain and/or distention, ileus, oliguria, or anuria. Blood tests may show an increase in creatinine levels. The diagnosis is confirmed with a cystogram. Similar to injuries that are diagnosed intraoperatively, small defects can be managed with bladder decompression using a Foley catheter, while larger defects may require surgical repair. In these cases, an urologist should be consulted for further guidance.

Fig. 22.2

Repair of cystotomy

22.4.2 Ureteral Injuries

The most common locations of ureteral injury in gynecologic surgery are at the cardinal ligament and at the level of the infundibulopelvic ligament [2, 9, 10]. In the cardinal ligament, the ureter passes beneath the uterine artery. It is usually less than 1 cm away from the uterine artery and 1.5 cm lateral to the cervix, although radiologic studies have shown that in cases involving cervical pathology, the ureter may be as close as 5 mm to the cervix [10]. At the level of the infundibulopelvic ligament, the ureter crosses over the pelvic brim and common iliac vessels and courses into the pelvis along the medial leaf of the broad ligament. Other sites where the ureter is particularly vulnerable to injury include the lateral border of the uterosacral ligament, the ovarian fossa, and the ureteric canal [2, 10].

Ureteral injuries can result from transection, crush, devascularization, or electrothermal damage. Because of the potential morbidity of these injuries, immediate recognition is important, although these are not commonly identified intraoperatively.

There are several measures that can be taken to avoid or reduce the risk of ureteral injury. Meticulous surgical technique and a thorough understanding of female pelvic anatomy are essential. Prior surgery, severe adhesive disease, endometriosis, enlarged uterus, fibroids, adnexal masses, and congenital anomalies all lead to distorted anatomy and tissue planes. Ideally, the ureter should be visualized before clamping any tissue pedicles. This can be done by retroperitoneal dissection, in which the round ligament is taken laterally and the peritoneum is dissected parallel to the infundibulopelvic ligament. After developing the pararectal and paravesical spaces, blunt dissection can be used to locate the ureter, which sits along or on the medial leaf of the broad ligament. Observation of vermiculation can help confirm that the correct structure has been identified.

In addition, when performing a hysterectomy, skeletonizing the uterine arteries, mobilizing the bladder down past the cervix, and deviating the uterus cranially with the use of a uterine manipulator will lateralize the ureters so that ligation of the uterine vessels and colpotomy can be performed safely [10]. Use of a cautery near the ureters should be minimized and, if necessary, hemostasis can be controlled with surgical clips. The degree of ureterolysis depends on the amount of visualization and mobilization necessary. In cases of extremely distorted pelvic anatomy, preoperative imaging or placement of ureteral stents may help to better delineate the course of the urinary tract.

If a ureteral injury is suspected, intravenous indigo carmine is administered. If there is no peritoneal extravasation, a cystoscopy is performed. The cystoscopy is used to assess for brisk efflux of dye from the bilateral ureteral orifices; sluggish efflux may be indicative of injury. Stents can also be fed through the ureters to evaluate for obstruction. If cystoscopy is not possible, stents can be fed through the ureters via cystotomy by making a small defect in the dome of the bladder. Retrograde filling of the bladder with dye and looking for leaks in the field may be useful in a limited number of cases; however, most injuries fail to demonstrate intra-operative intraperitoneal leaks [2]. Thermal injuries and partial transections are especially difficult to recognize, as they may not be identifiable by any of the above methods.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree