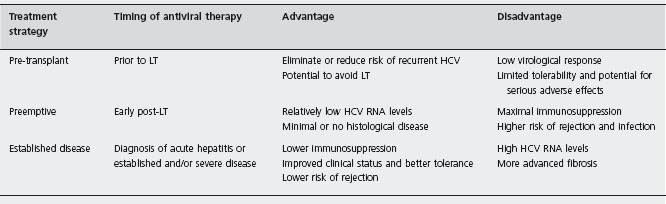

Pre-transplant antiviral therapy

Pre-transplant antiviral therapy is an attractive approach in which those with undetectable HCV RNA going into transplant may eliminate the risk of developing recurrent HCV. In some cases when patients achieve SVR from this regimen, they may completely avoid transplantation altogether. A recent review shows that up to two-thirds of patients who obtain SVR prior to liver transplantation will remain free of HCV in the post-transplant setting. This rate is lower for patients without achievement of SVR [21]. Unfortunately, this is a difficult group to treat given low response rates due to the high prevalence of genotype 1 and underlying cirrhosis and its associated side effects (e.g. leukopenia, thrombocytopenia).

Table 44.3 Contributing factors leading to lower response rates to antiviral therapy in liver transplant patients.

|

One of the largest studies of pre-transplant antiviral therapy by Everson et al. described their experience with a low accelerating dose regimen (LADR) of primarily non-pegylated interferon and ribavirin and its efficacy for HCV clearance prior to transplant [22]. A total of 124 patients (70% genotype 1 and 63% having Child-Pugh class B or C) were treated, with 24% achieving SVR (13% genotype 1 and 50% non-genotype 1). Twelve out of 15 (80%) of patients who were HCV RNA negative going into transplant remained HCV RNA negative at least six months after LT.

Three comparative studies of peginterferon in liver transplant candidates (although included patients were not necessarily already considered or placed on transplant listing) have been reported [23–25]. DiMarco et al. reported results of 102 patients (67% treatment naive) randomized to receive peginterferon α-2b monotherapy or peginterferon plus ribavirin (800 mg) for up to 52 weeks (treatment was stopped if HCV RNA was not undetectable at 24 weeks) [23]. Overall, SVR was 19.6% in the peginterferon and ribavirin group and 9.8% in peginterferon mono-therapy group (p = 0.06). Not surprising, response rates for non-genotype 1 were higher than for genotype 1 (66% vs 11%, p = 0.001). Discontinuation was 27% in the peginterferon and ribavirin group and 41% in the peginterferon group. Helbling et al. randomized 124 naive patients to either peginterferon α-2a plus standard dose ribavirin (1000–1200mg) or peginterferon plus low dose ribavirin (600–800 mg) for 48 weeks [24]. SVR was 50% with the standard dose ribavirin group compared to 38% for the lower dose group (p = 0.153). Both groups had similar rates of treatment discontinuation. Finally, in a nonrandomized controlled trial, the first to specifically assess the effect of antiviral therapy on liver function in patients with decom-pensated HCV cirrhosis, Iacobellis et al. compared 66 patients treated with peginterferon α-2b and ribavirin (800–1000mg) to 63 controls (no treatment). Twenty percent of the treatment group achieved SVR [25]. The study had similar discontinuation rates for the treatment group as observed in prior studies and survival was not different between the two groups, but a post hoc analysis showed a survival benefit in the treated group. An important finding in this study was a decreased incidence of decompensation (ascites, hepatic encephalopathy) in the treated group compared to the controls during follow-up. However it did not translate into increased survival in the treated patients.

In summary, pre-transplant antiviral therapy should be strongly considered in patients with cirrhosis who have Child-Pugh scores ≤ 7 or Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores ≤ 18 [8]. (MELD score = 10 [0.957Ln (serum creatinine) + 0.378Ln (total bilirubin) + 1.12Ln (INR) + 0.643].) B2 A special group that should be strongly considered for antiviral therapy while awaiting transplantation are patients with well compensated liver disease upgraded on the transplant list solely for an indication of hepatocellular carcinoma, especially if they are non-genotype 1. B4 Our program attempts to make these patients HCV RNA negative on treatment for at least two months before proceeding with either cadaveric or living donor transplantation. However, it is important to emphasize that the majority of HCV-infected patients without hepatocellular carcinoma will not be optimal candidates for antiviral therapy by the time they have moved up on the transplant list, due to their disease severity.

Preemptive antiviral treatment

Preemptive treatment refers to early antiviral therapy days to weeks after LT, before the development of histological recurrence. A number of theoretical advantages exist with this approach in that patients have lower HCV RNA levels and lack histological disease. However, from a clinical standpoint, treatment at this time is most challenging due to poor clinical status, cytopenias from maximal immuno-suppression, and higher rates of rejection and infection in the early transplant period. Only about 60% of LT recipients are eligible for preemptive therapy, with the need for dose reduction occurring in up to 50% of treated patients [26]. A recent meta-analysis found no studies of preemptive therapy that satisfied inclusion for analysis [19]. In summary, the efficacy of preemptive anti-viral therapy remains to be defined and should only be considered in patients undergoing retransplantation for rapidly progressive HCV recurrence [8].

Treatment of established disease

Given the lack of efficacy and limitations of preemptive therapy, many transplant centers have opted to delay treatment until significant recurrent disease is verified. By taking this approach, treatment is focused on those likely to achieve benefit with antiviral therapy, avoiding unnecessary toxicity and side effects in those without significant disease recurrence. Two general approaches have been used to treat established disease. One approach initiates antiviral treatment at the diagnosis of acute recurrent hepatitis utilizing liver biopsy to exclude other causes for elevated liver enzymes, such as rejection. The second approach followed by most transplant centers is to initiate antiviral therapy when clinically significant evidence of recurrence exists. This latter approach utilizes protocol and/or clinically indicated liver biopsies reporting both the grade and stage of recurrent disease.

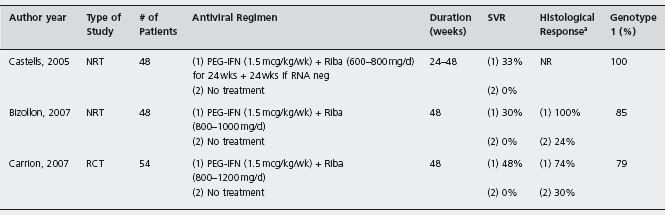

Table 44.4 Published of controlled trials utilizing peginterferon and ribavlrin for treating recurrent HCV vs no treatment.

NRT: nonrandomized trial; RCT: randomized controlled trial; Riba: ribavirin; SVR: sustained virological response; NR: not reported. a Defined as fibrosis stabilization (same fibrosis stage) or fibrosis improvement (reduction of >/= 1 fibrosis stage).

Protocol liver biopsies in patients transplanted for HCV may be useful given the potential for significant fibrosis progression and has largely become standard of care [8]. Since fibrosis progression is not linear over time, possibly progressing more rapidly in the first post-LT year, the 12-month liver biopsy has the ability to stratify fibrosis progression. Those developing severe disease recurrence within the first transplant year are at a high likelihood of progressing to cirrhosis and should be considered for antiviral therapy [14, 27]. Furthermore, the absence of fibrosis 12 months post-LT is associated with excellent cirrhosis-free survival [14]. The measurement of hepatic venous pressure gradients (HVPG; wedged hepatic vein pressure minus free hepatic vein pressure) appears to be a useful tool in assessing disease severity in recurrent HCV [28]. HVPG measurements ≥6mmHg in one study [29], or ≥10mmHg in another study [5], at one year post-LT have been shown to be extremely accurate in predicting clinical decompensation over liver biopsy. The same group has also shown good correlation between HVPG measurements and histological response with antiviral therapy [30]. In summary, patients with fibrosis stage ≥ 2 out of 4, severe inflammation (grade 3 or 4), evidence of significant hepatic dysfunction (elevated bilirubin, prolonged prothrombin time), or HPVG gradients ≥6 should be strongly considered for antiviral therapy [5, 8] B4

Controlled trials of peginterferon and ribavirin

The current standard of care for treating established recurrent HCV is pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy. Multiple studies using various study designs and end-points have been performed to evaluate the efficacy of established disease therapy after transplantation, with end-points consisting of SVR, histological improvement, and allograft and patient survival. It appears that there is no significant correlation between success of antiviral therapy and the interval of time from transplant and start of antiviral therapy. There are only three comparative studies of peginterferon and ribavirin in treatment of established recurrent HCV (see Table 44.4 and Figure 44.1) with only one randomized study [30–32].

Castells et al.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree