Resection is a means of improving survival in patients with gallbladder cancer. A more aggressive surgical approach, including resection of the gallbladder, liver, and regional lymph nodes, is advisable for patients with T1b to T4 tumors. Aggressive resection is necessary because a patient’s gallbladder cancer stage determines the outcome, not the surgery itself. Therefore, major resections should be offered to appropriately selected patients. Patients with advanced tumors or metastatic disease are not candidates for radical resection and thus should be directed to more suitable palliation.

Epidemiology and risk factors

Gallbladder cancer (GBCA) is the fifth most common gastrointestinal cancer and the most common biliary tract malignancy in the United States, with an incidence of 1.2 per 100,000 persons per year. Because of its tendency to present at an advanced stage, it has historically been considered an incurable disease with a dismal prognosis. In appropriately selected cases, radical surgery is possible and offers some patients a chance at long-term survival. Despite this, in the majority of cases, the outcomes of patients with advanced GBCA remain poor.

There are many known risk factors for GBCA, including cholelithiasis, obesity, multiparity, and typhoid fever. In addition, there are geographic variations in the prevalence of the disease, with rates highest in Chile, India, Israel, Poland, and Japan. In the United States, the disease prevails in Native American women from New Mexico. Gallstones are present in the majority of patients; however, the relationship between causation and association is unclear. In some cases of GBCA, a focus of cancer may be found in a gallbladder adenomatous polyp; however, in the majority of cases, small polyps of the gallbladder do not harbor malignancy and are non-neoplastic and may be simply observed. Polyps greater than 1 cm, those arising in the setting of primary sclerosing cholangitis, or those discovered in patients older than 50 years of age are more likely to harbor cancers and, therefore, should be treated with cholecystectomy if a patient is an appropriate candidate for surgery.

Clinical presentation

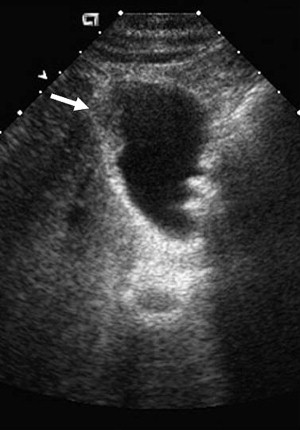

In general, the symptoms associated with GBCA are nonspecific. As a result, most patients present at an advanced, inoperable stage. If patients do have symptoms, they are most commonly abdominal pain or biliary colic. It may be seen in the initial assessment as an asymmetric mass detected on a routine ultrasound (US) in the work-up of biliary symptoms ( Fig. 1 ). In advanced cases of invasion or compression of the porta hepatis, jaundice may ensue and the patients may have systemic signs, such as malaise and weight loss. Jaundice is an ominous finding. In a series from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center from 1995 through 2005, one-third of patients presented with jaundice and only 7% had resectable disease.

Clinical presentation

In general, the symptoms associated with GBCA are nonspecific. As a result, most patients present at an advanced, inoperable stage. If patients do have symptoms, they are most commonly abdominal pain or biliary colic. It may be seen in the initial assessment as an asymmetric mass detected on a routine ultrasound (US) in the work-up of biliary symptoms ( Fig. 1 ). In advanced cases of invasion or compression of the porta hepatis, jaundice may ensue and the patients may have systemic signs, such as malaise and weight loss. Jaundice is an ominous finding. In a series from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center from 1995 through 2005, one-third of patients presented with jaundice and only 7% had resectable disease.

Pathology and staging

According to the most recent American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging algorithm ( Table 1 ), GBCAs are staged according to tumor depth of invasion (T), presence of lymph node metastasis (N), and presence of distant metastasis (M). Most GBCA is adenocarcinoma; however, less commonly, other histopathologic variants are seen, such as papillary, mucinous, squamous, and adenosquamous subtypes.

| Category | T | N | M | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS | Carcinoma in situ | — | — | |

| 1 | a | Tumor invades lamina propria | Metastatic lymph nodes in hepatoduodenal ligament | Distant metastasis |

| b | Tumor invades muscle layer | |||

| 2 | Tumor invades perimuscular connective tissue with no extension beyond serosa or into liver | — | — | |

| 3 | Tumor perforates the serosa or directly invades 1 adjacent organ or both or ≤2 cm extension into liver | — | — | |

| 4 | Tumor extends >2 cm into liver or into 2 or more adjacent organs | — | — | |

T stage describes how deeply the primary tumor invades through the layers of the gallbladder wall and into adjacent structures. This component is the most important factor in determining appropriate surgical therapy in patients with potentially resectable tumors. The wall of the gallbladder consists of a mucosa, lamina propria, a thin muscular layer, perimuscular connective tissue, and a serosa. The gallbladder wall adjacent to the liver does not have a serosal covering, making the gallbladder and liver more contiguous than the peritoneal viscera. In general, tumors confined to the gallbladder wall are classified as T1 or T2 whereas T3 and T4 tumors have extended beyond the gallbladder ( Fig. 2 ).

N staging refers to the presence or absence of metastasis to regional lymph nodes, which are generally confined to the hepatoduodenal ligament, such as hilar, celiac, periduodenal, peripancreatic, and superior mesenteric nodes as well as nodes along the pancreatic head. If patients have positive nodes outside these areas, they are considered as having distant metastatic disease. Beyond regional lymph nodes, the most common sites of distant metastasis in GBCA are the peritoneum and the liver. Occasionally, spread to the lung and pleura is seen at presentation, but these sites are uncommon in the absence of apparent metastatic disease in the abdomen.

There is a direct correlation between the incidence of disseminated metastasis or nodal disease and T stage. In other words, tumors that have invaded more deeply into the gallbladder wall are more likely to have spread to regional nodes or distant sites. A study from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center demonstrated that distant and nodal metastases increased progressively from 16% to 79% and from 33% to 69%, respectively, in going from T2 to T4 tumors. The current AJCC stage groupings for GBCA reflect the clinical treatment status of the disease, in most cases. GBCA categorized as stages I or II are potentially resectable with curative intent; stage III generally indicates locally unresectable disease as a consequence of vascular invasion or involvement of multiple adjacent organs; and stage IV represents unresectability as a consequence of distant metastases ( Table 2 ).

| Stage | TNM Grouping |

|---|---|

| 0 | TisN0M0 |

| IA | T1N0M0 |

| IB | T2N0M0 |

| IIA | T3N0M0 |

| IIB | T1-3N0M0 |

| III | T4NxM0 |

| IV | TxNxM1 |

In considering preoperative staging of GBCA, the approach is dependent on a variety of clinical factors related to how a patient presents. Patients generally present in 1 of 3 different ways: GBCA suspected preoperatively; GBCA found intraoperatively at the time of cholecystectomy for presumed benign disease; and, finally, the most common situation, GBCA is diagnosed incidentally on pathologic examination after cholecystectomy. It should be routine to inspect the gallbladder lumen after simple cholecystectomy to ensure there are no suspicious mucosal lesions. This is a safe and fast screening technique while a patient is in the operating room and permits the immediate assessment of suspicious lesions with frozen section.

Staging is primarily achieved through imaging. US is usually the initial radiographic study obtained in the context of the work-up of presumed benign gallbladder diseases. Typically, GBCA has characteristic features on US: a mass replacing or filling the gallbladder or invading the gallbladder bed, an intraluminal growth or polyp, or asymmetric gallbladder wall thickening. In cases of locally advanced disease, US has a sensitivity of 85% and an overall accuracy of 80% in diagnosing GBCA. US can fail to detect GBCA if the cancer is subtle or flat and if there is substantial cholelithiasis. Higher flow on color Doppler US can be indicative of a focus of malignancy and may assist in diagnosis. US also has the ability to determine involvement of the biliary tree and porta hepatis. Similarly, it can accurately assess liver parenchymal invasion.

All patients who have suspected GBCA should undergo staging in the form of cross-sectional imaging with CT or MRI to look for lymph node or distant metastatic disease. These modalities can also help assess depth of invasion into the liver to facilitate operative planning for the extent of potential resection. Ohtani and colleagues reported the positive predictive value of conventional CT scan for detecting involvement in various lymph node stations as 75% to 100% despite lower sensitivity as 17% to 78%. The same group has reported the sensitivity of CT scan to detect of tumor invasion into liver, bile duct, or other adjacent organs, such as pancreas and transverse colon as 50% to 65% and the positive predictive value as 77% to 100%. CT is similarly sensitive at detecting invasion into liver or other adjacent organ was with sensitivities ranging from 80% to 100%. MRI is less frequently used for staging of GBCA, but sometimes the use of magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRCP) or magnetic resonance angiography provides more information than US or CT. Schwartz and colleagues demonstrated, in a retrospective analysis of 34 patients with GBCA, that combination of conventional MRI and MRCP achieved a sensitivity of 100% for liver invasion and 92% for lymph node involvement.

As in many other intra-abdominal malignancies, fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scanning is increasingly used. PET scans may have a role in detecting residual disease in the gallbladder fossa post cholecystectomy or in detecting occult metastatic disease. It has been shown that additional information from PET alters management in 23% of selected patients with GBCA who were preoperatively staged using US/CT/MRI. Currently, the role of FDG-PET scanning in the work-up of patients with suspected GBCA is not routine. In cases where there is suspicion of metastatic disease that is not completely appreciated on conventional cross-sectional studies, it may be helpful in delineating suspicious masses as malignant or benign.

Surgical management based on T stage

A patient’s histologic T stage is the most important determinant of the necessary extent of resection. In the case of patients with incidental GBCAs, it is especially important in aiding in the selection of patients for reoperation and definitive resection. T stage in GBCA is positively correlated with nodal and distant metastasis and the potential for residual liver disease. In general, it is preferable for the first operation for GBCA to be definitive; however, it has been demonstrated that a prior noncurative cholecystectomy may not have an adverse impact on survival after reoperation and definitive R0 resection. Published series on this topic, however, likely suffer from publication bias, as such analyses only include patients who are submitted to resection and exclude patients with disseminated disease. The logical question that ensues is how many patients with disseminated disease have metastases because the initial operation violated the tumor plane.

There are other reasons why early preemptive identification of patients with GBCA is technically favorable to a reoperative approach. After cholecystectomy, patients naturally form adhesions in the portal hepatis and gallbladder fossa, which can make it difficult to distinguish benign scar tissue and tumor. This in turn may lead to more extensive resections than would otherwise be necessary and could result in unnecessary biliary or liver resections.

In most cases, before proceeding with laparotomy for GBCA, staging laparoscopy is helpful to assess the abdomen for evidence of peritoneal spread or discontiguous liver disease and may spare up to 48% of patients an unnecessary laparotomy. Although laparoscopy is useful in staging, laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be avoided in cases where there is a high preoperative probability of cancer due to the risk of tumor dissemination. In suspicious cases, open assessment should be planned and frozen section should be done to establish a diagnosis of malignancy. If a frozen section is positive for malignancy, hepatic resection may follow. Due caution should be exercised for tumors abutting the liver and preemptive liver resection may be a safer approach in such patients to prevent tumor spillage.

In cases where the diagnosis of GBCA is made at the time of exploration for what had been presumed benign disease, if the treating surgeon is not prepared to perform a hepatic resection, the patient is best served by transfer to a center with experience in performing the appropriate operation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree