Gallbladder polyps are frequently encountered on cross-sectional imaging, often in asymptomatic patients. Most are benign and of little clinical importance. However, some polyps do have a malignant potential. This article discusses the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and natural history of gallbladder polyps and risk factors for malignant polyps and indications for cholecystectomy.

The increasing use and constantly improving resolution of abdominal imaging modalities in clinical practice often lead to “abnormal” findings that are of unclear significance. Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder are a prime example of this, as they are frequently diagnosed on routine transabdominal ultrasounds. Any projection of mucosa into the lumen of the gallbladder is defined as a polypoid lesion of the gallbladder, regardless of the neoplastic potential. Many gallbladder polyps are often diagnosed incidentally following cholecystectomy for gallstones or biliary colic. The estimated prevalence of gallbladder polyps varies by the demographics of the studied population, but it is generally considered to be around 5%. The vast majority of gallbladder polyps are benign, and gallbladder cancer is a very rare disease. The estimated new cases of gallbladder and other biliary cancers only represented 0.66% of the estimated new cancer cases in the United States in 2009, accounting for only 0.60% of estimated new cancer deaths. This article discusses the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and natural history of gallbladder polyps, as well as risk factors for malignant polyps and indications for cholecystectomy.

Classification

A classification of benign tumors and pseudotumors of the gallbladder was first proposed in 1970. Benign tumors include adenomas, lipomas, hemangiomas, and leiomyomas. Benign pseuodotumors include adenomyomas, cholesterol polyps, inflammatory polyps, and heterotopic mucosa from the stomach, pancreas, or liver. The current accepted classification divides these polyps into neoplastic (adenomas, carcinoma in situ) and non-neoplastic, with the non-neoplastic polyps accounting for about 95% of these lesions.

The most common of the non-neoplastic polyps is the cholesterol polyp. These result when the lamina propria is infiltrated with lipid-laden foamy macrophages. Cholesterol polyps account for about 60% of all gallbladder polyps and are generally less than10 mm. Often, multiple cholesterol polyps are present. Adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder is a benign, hyperplastic lesion caused by excessive proliferation of surface epithelium, which can then invaginate into the muscularis. Adenomyomatosis accounts for about 25% of gallbladder polyps and usually localizes to the gallbladder fundus appearing as a solitary polyp ranging in size from 10 to 20 mm. Adenomyomatosis is not considered neoplastic. Inflammatory polyps account for about 10% of gallbladder polyps and result from granulation and fibrous tissue secondary to chronic inflammation. They are typically less than 10 mm in size and are not neoplastic.

Adenomas account for about 4% of gallbladder polyps and are considered neoplastic. They range in size from 5 to 20 mm, are generally solitary, and are often associated with gallstones. Whether or not gallbladder adenomas progress to adenocarcinomas is not clear. Several studies do support this potential progression. Kozuka and colleagues analyzed 1605 cholecystectomy specimens and found histological, traceable transitions from the 11 benign adenomas, 7 adenomas with malignancy changes, and 79 invasive carcinomas. Other case reports support this adenoma-to-cancer progression. However, this progression is not felt to be the predominant pathway of carcinogenesis in the gallbladder, and K-ras mutations have not been detected in gallbladder carcinomas associated with an adenoma.

Finally, rare miscellaneous neoplastic polyps of varying sizes account for the remaining 1% of gallbladder polyps and include leiomyomas, lipomas, neurofibromas, and carcinoids.

Clinical presentation

Gallbladder polyps are generally thought not to cause any symptoms, though most of the prevalence studies did not assess symptoms. Polyps are sometimes identified on transabdominal ultrasounds done for right upper quadrant pain. In the absence of other findings, the gallbladder polyp may be considered a source of biliary colic. Terzi and colleagues reported that, in a series of 74 patients undergoing cholecystectomy for gallbladder polyps, 91% had symptoms, most commonly right upper quadrant pain, nausea, dyspepsia, and jaundice. However, about 60% of the patients also had gallstones, so it is unclear whether the polyps were primarily driving the symptoms. There was no difference in presenting symptoms between patients with benign versus malignant polyps. In another large retrospective analysis of 417 patients found to have gallbladder polyps on abdominal ultrasound, 64% of these polyps were diagnosed during a work-up of unrelated illness. Twenty-three percent had abdominal symptoms, and 13% had elevated liver function tests.

Cholesterol polyps may detach and behave clinically as a gallstone, causing biliary colic, obstruction, or even pancreatitis. There are also reports of gallbladder polyps causing acalculous cholecystitis and, even, massive hemobilia.

Risk Factors

In contrast to the well-known risk factors for gallstones, attempts to identify risk factors for developing gallbladder polyps have not shown any consistent relationship between formation of polyps and age, gender, obesity, or medical conditions such as diabetes. There is some literature to suggest an inverse relationship between gallbladder polyps and stones. Jorgensen and Jensen studied 3608 asymptomatic patients and found gallbladders with both polyps and stones in only 3 patients. The investigators hypothesized that polyps either mechanically disrupt the formation of stones or that polyps are harder to diagnose radiographically when stones are present. Patients with congenital polyposis syndromes such as Peutz-Jeghers and Gardner syndrome can also develop gallbladder polyps. A recent large retrospective analysis of risk factors for gallbladder polyps in the Chinese population identified chronic hepatitis B as a risk factor. Proposed patient risk factors for malignant gallbladder polyps include age greater than 60, presence of gallstones, and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Polyp risk characteristics include a size greater than 6 mm, solitary, and sessile.

Clinical presentation

Gallbladder polyps are generally thought not to cause any symptoms, though most of the prevalence studies did not assess symptoms. Polyps are sometimes identified on transabdominal ultrasounds done for right upper quadrant pain. In the absence of other findings, the gallbladder polyp may be considered a source of biliary colic. Terzi and colleagues reported that, in a series of 74 patients undergoing cholecystectomy for gallbladder polyps, 91% had symptoms, most commonly right upper quadrant pain, nausea, dyspepsia, and jaundice. However, about 60% of the patients also had gallstones, so it is unclear whether the polyps were primarily driving the symptoms. There was no difference in presenting symptoms between patients with benign versus malignant polyps. In another large retrospective analysis of 417 patients found to have gallbladder polyps on abdominal ultrasound, 64% of these polyps were diagnosed during a work-up of unrelated illness. Twenty-three percent had abdominal symptoms, and 13% had elevated liver function tests.

Cholesterol polyps may detach and behave clinically as a gallstone, causing biliary colic, obstruction, or even pancreatitis. There are also reports of gallbladder polyps causing acalculous cholecystitis and, even, massive hemobilia.

Risk Factors

In contrast to the well-known risk factors for gallstones, attempts to identify risk factors for developing gallbladder polyps have not shown any consistent relationship between formation of polyps and age, gender, obesity, or medical conditions such as diabetes. There is some literature to suggest an inverse relationship between gallbladder polyps and stones. Jorgensen and Jensen studied 3608 asymptomatic patients and found gallbladders with both polyps and stones in only 3 patients. The investigators hypothesized that polyps either mechanically disrupt the formation of stones or that polyps are harder to diagnose radiographically when stones are present. Patients with congenital polyposis syndromes such as Peutz-Jeghers and Gardner syndrome can also develop gallbladder polyps. A recent large retrospective analysis of risk factors for gallbladder polyps in the Chinese population identified chronic hepatitis B as a risk factor. Proposed patient risk factors for malignant gallbladder polyps include age greater than 60, presence of gallstones, and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Polyp risk characteristics include a size greater than 6 mm, solitary, and sessile.

Diagnosis

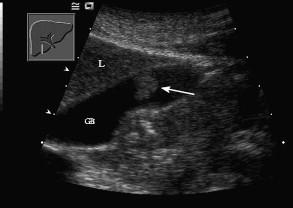

Most gallbladder polyps are diagnosed during a routine abdominal ultrasound. They appear as fixed, hyperechoic material protruding in to the lumen of the gallbladder, with or without an acoustic shadow ( Fig. 1 ). However, the accuracy of abdominal ultrasound for diagnosing these lesions has been questioned. Abdominal ultrasound is often limited by the body habitus of the patient, and technical limitations can lead to intraobserver variability in interpretation. Yang and colleagues found that abdominal ultrasound was quite sensitive (90%) and specific (94%) in diagnosing gallbladder polyps, particularly when there are no gallstones present. However, Akyurek and colleagues found that abdominal ultrasound was only 20% sensitive in diagnosing polyps less than 1 cm and 80% sensitive in diagnosing polyps greater than 1 cm. The investigators concluded that abdominal ultrasound was inaccurate in 82% of cases of these polyps. Also, in another large retrospective study of 417 patients with gallbladder polyps found on abdominal ultrasound, one-third of those patients did not have polyps found at cholecystectomy. Chattopadhyay and colleagues analyzed a retrospective case series of 23 patients who were diagnosed preoperatively with a gallbladder polyp by abdominal ultrasound. When using 10 mm size as the cut-off criteria, the investigators noted 100% sensitivity, 87% specificity, and positive predictive value of 50% in the diagnosis of malignancy in gallbladder polyps. Abdominal ultrasound is generally considered the first of line study for making this diagnosis, it is by no means a definitive indicator of the presence of a gallbladder polyp or its malignant potential.

Role of Endoscopic Ultrasound

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has gained widespread use for the diagnosis of gastrointestinal malignancies, submucosal lesions of the gastrointestinal tract, and abnormalities seen on cross-sectional imaging. Its role in evaluating the biliary tree has been well defined, and this includes a possible role in the management of gallbladder polyps. Because the gallbladder lies directly on the gastric antrum and duodenal bulb, the EUS probe can be placed immediately adjacent to the gallbladder. This small distance between the probe and the gallbladder allows for scanning at high frequencies, thereby creating very high-resolution images. Sugiyama and colleagues examined a case series of 194 patients who underwent both abdominal ultrasound and EUS for evaluation of gallbladder polyps less than or equal to 20 mm. Fifty-eight of these patients went to surgery, and the EUS preoperative diagnosis was cholesterol polyp in 34 patients, adenomyomatosis in 7 patients, and neoplastic lesions in 17 patients. The accuracy of EUS in correctly distinguishing the polyp was 97%, superior to the 76% accuracy of abdominal ultrasound. Another study attempted to define EUS criteria that could help determine the risk of underlying neoplasia in gallbladder polyps between 5 and 15 mm in diameter. Polyps were more likely to be neoplastic if there was loss of definition of the muscularis propria; if they were solitary, sessile, and lobulated; and if their echo pattern was isoechoic to the liver with heterogeneous echotexture. These criteria were used to create an EUS score ranging from 0 to 20 points. When a cut-off score of 6 or greater was used, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of diagnosing a neoplastic polyp was 81%, 86%, and 83.7%, respectively.

Whether EUS alone can be used to determine a treatment strategy for gallbladder polyps is not clear. Cheon and colleagues reviewed a case series of 365 patients who underwent EUS for evaluation of gallbladder polyps less than 20 mm in diameter. Of these, 94 patients underwent cholecystectomy. Neoplastic lesions were found in 19 patients (17 adenomas and 2 adenocarcinomas), and, of these patients, 10 had polyps 5 to 10 mm in diameter. EUS was 88.9% sensitive in diagnosing neoplastic disease in polyps greater than 1.0 cm. However, EUS was only 44.4% sensitive in diagnosing malignant disease in polyps less than 1.0 cm, leaving the investigators to conclude that EUS alone is not sufficient in determining the course of treatment in polyps less than 1.0 cm. On the other hand, Cho and colleagues found that the finding of hypoechoic areas in the core of gallbladder polyps less than 20 mm in size was 90% sensitive and 89% specific in predicting neoplastic polyps. Akatsu and colleagues, in cases series of 29 patients with gallbladder polyps 10 to 20 mm, determined that aggregation of hyperechoic spots and multiple microcysts are predictors of cholesterol polyps and adenomyomatosis, respectively, which are non-neoplastic polyps. EUS may be more accurate than transabdominal ultrasound in determining whether gallbladder polyps are neoplastic, though there is not enough evidence to suggest that EUS is the one definitive diagnostic modality for making this determination.

Other Imaging Modalities

Other imaging modalities have also been studied. Koh and colleagues presented a case series of three patients with gallbladder polyps that were correctly diagnosed preoperatively as benign or malignant with the use of positron emission tomography scanning with 18F-labelled deoxyglucose. Jang and colleagues prospectively followed 144 patients found to have 1 cm gallbladder polyps who eventually underwent cholecystectomy. Preoperatively, each patient underwent evaluation with high-resolution transabdominal ultrasound, EUS, and CT scan. High-resolution ultrasound is a new technology using a broad bandwidth MHz linear array probe. The diagnostic sensitivity for malignancy of the high-resolution ultrasound was comparable to that of EUS (90% vs 86%, respectively), and both were better than CT scan (72%). The investigators concluded that high-resolution transabdominal ultrasound may therefore be another important imaging modality for gallbladder polyps.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree