Management of Foreign Bodies

Marvin L. Corman

Homo sum; humani nil a me alienum puto.

[I am a man, and nothing human is foreign to me.]

—TERENCE (185-159 BC): Heauton Timorumenos, Act I

In ancient times, it was customary to open the stomach to remove knives that had been accidentally swallowed, but it was not until 1807 that White excised a silver spoon from the intestines.7,22 The ingestion of foreign materials may occur accidentally (e.g., swallowed dental bridge, nail, screw, paper clip, toothpick, chicken bone [Figures 18-1 and 18-2 ]) or it may be intentional (e.g., in psychiatric or prison populations).16 Occasionally, a physician may be responsible for the introduction of a foreign body that requires special efforts to remove (Figure 18-3). Once an item passes beyond the pylorus, it usually can be eliminated without difficulty. One area of relative hindrance to passage, however, is the terminal ileum. Erosion can occur, which may lead to perforation, abscess, and fistula formation. For example, a case of aortocolic fistula caused by an ingested chicken bone has been reported.6 Risk factors that increase the probability of foreign body perforation include inflammatory bowel disease, adhesions, diverticular disease, Meckel’s diverticulum, tumors, and hernias.14 Shillingstad and colleagues categorize four groups of patients who are at risk for foreign body ingestion19:

Children up to 5 years of age with accidental ingestion (e.g., buttons, coins)

Adults who present with food impaction, often related to being edentulous

Individuals who have accidentally or deliberately ingested a foreign body

Individuals attempting to profit from drug smuggling (i.e., “mules”—also known as “body packers” or “body baggers”). Rupture or impaction can lead to fatal drug toxicity.

▶ EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT OF INGESTED FOREIGN BODIES

Stable patients who have swallowed small, smooth objects; who have no evidence of esophageal entrapment and otherwise negative imaging studies; and with no evidence of peritoneal irritation can often be managed conservatively with follow-up the next day. Passage of objects in the stool may take several days to weeks, especially with children, and in these circumstances, parents should observe for their presence. Generally, if the object passes into the stomach, it will negotiate its way through the entire gastrointestinal tract. However, objects greater than 2 cm in diameter or greater than 6 cm in length or those that are sharp should undergo serial x-rays and be observed closely for peritoneal signs.

Narcotic “body packers’drug mules” should be followed up and monitored as inpatients due to the risk of drug toxicity. They may need bowel irrigation and/or surgical intervention if there is evidence of systemic effects of leaking narcotics (endoscopy is not recommended as it tends to release drugs from the packages).20

Adult patients with esophageal entrapment of food bolus or other food-related objects should be considered for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, especially to rule out a malignant stricture. Handheld metal detectors can be used to trace the passage of metallic objects through the gastrointestinal tract

and reduce exposure to ionizing radiation. Obviously, any individual with peritoneal signs needs radiologic investigation and/or exploratory laparotomy.

and reduce exposure to ionizing radiation. Obviously, any individual with peritoneal signs needs radiologic investigation and/or exploratory laparotomy.

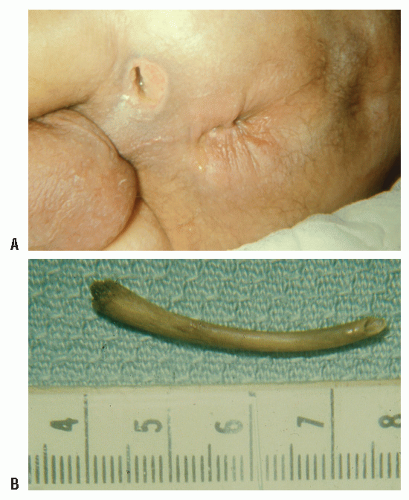

FIGURE 18-1. A: Perforation of the rectum from an ingested foreign body that produced an ischiorectal abscess. B: A chicken bone was the cause of the perforation. (Courtesy of Daniel Rosenthal, MD.) |

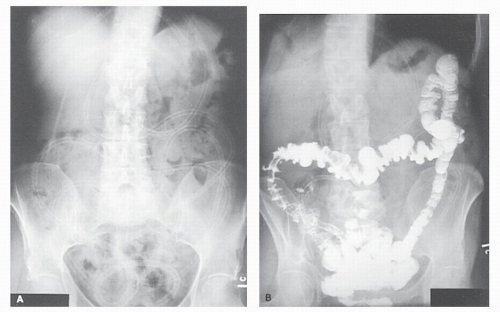

FIGURE 18-2. An accidentally swallowed wood screw is lodged in the cecum. Because of peritoneal signs, a laparotomy was undertaken. (Courtesy of Albert Medwid, MD.) |

▶ FOREIGN BODIES OF THE RECTUM

The list of objects that have been removed from the rectum is virtually endless (e.g., lightbulbs, catheters, pens and pencils, glass tubes, candles, vibrators, dildos, bottles and jars; Figures 18-4,18-5,18-6,18-7,18-8,18-9 and 18-10). The story of the discovery of a deceased gerbil in the rectum is probably of questionable authenticity. Busch and Starling identified 182 cases from the world’s literature and noted the recovery of objects from A (i.e., apple) to Z (i.e., zucchini).5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree