ISGPF parameters for postoperative pancreatic fistula grading

Grade

A

B

C

Clinical condition

Well

Often well

Ill-appearing/bad

Specific treatmenta

No

Yes/no

Yes

US/CT (if obtained)

Negative

Negative/positive

Positive

Persistent drainage (after 3 weeks)b

No

Usually yes

Yes

Re-operation

No

No

Yes

Death related to POPF

No

No

Possibly yes

Signs of infection

No

Yes

Yes

Sepsis

No

No

Yes

Re-admission

No

Yes/no

Yes/no

Given the fragile nature of the pancreatic anastomosis and its propensity to leak, many variations have been described with various advantages and disadvantages touted for each. Despite numerous studies comparing the type and style of anastomosis (pancreaticojejunostomy vs. pancreaticogastrostomy, [6–9] duct-to-mucosa vs. invagination technique, [10] pancreatic duct stent vs. no stent [11–13], the choice for management of the distal pancreatic remnant is still largely a matter of surgeon preference and comfort. The authors prefer a modified Blumgart two-layer pancreaticojejunostomy with an outer layer of 2-0 silk horizontal mattress sutures and an inner duct-to-mucosa layer of 5-0 polydioxanone (PDS) performed end-to-side. However, in an experienced pancreaticobiliary surgeon’s hands, several approaches may have similar outcomes.

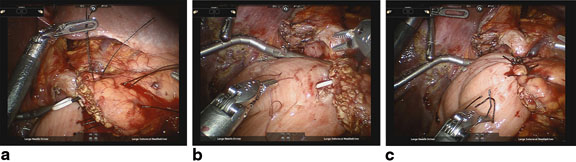

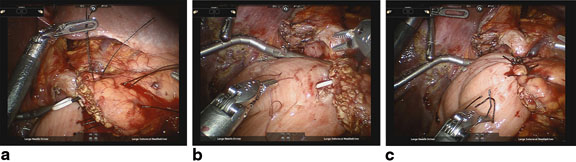

Anastomosis begins by dissecting 2–3 cm of the pancreatic stump from surrounding tissues (Fig. 27.1a–c). The jejunal limb is brought through the duodenal hiatus or another retrocolic window is made in the transverse colon mesentery and positioned to allow creation of a tension-free end-to-side anastomosis. Interrupted horizontal mattress sutures of 2-0 silk are placed using transpancreatic bites of pancreas and seromuscular bites of jejunum (Fig. 27.1a). The needles are left on these sutures and used for the anterior seromuscular buttressing layer later. Care must be taken not to suture the pancreatic duct; thus, a temporary 5F or 7F Hobbs ERCP stent (Hobbs Medical, Stafford Springs, CT) is placed in the duct to help prevent inadvertent occlusion. Three sutures are required for the posterior row: one superior, one straddling the pancreatic duct, and one inferiorly. The middle stitch is placed while moving the stent in the duct to assure the knot is not tied too tight. Next, a 2–3 mm enterotomy is made in the jejunum, and the inner suture line is constructed with interrupted 5-0 PDS. Beginning at the superior aspect of the gland, the suture line incorporates the pancreatic duct and full-thickness jejunum. Depending on the size of the duct, it is usually possible to place three to five sutures in a duct-to-mucosa fashion in the anterior and posterior rows, each. After the posterior suture line is complete, it is tied down and the Hobbs stent is inserted into the pancreatic duct with the curved end inserted into the jejunum (Fig. 27.1b). The anterior suture line is formed. Finally, the anterior row of 3-0 silk mattress sutures are placed using seromuscular bites of jejunum secured to the capsule of the pancreas. In tying the sutures, take extreme care to avoid pulling the sutures through the tissue when attempting to imbricate the jejunum over the anastomosis, particularly when the pancreas is soft (Fig. 27.1c). A #19 round channel drain is placed in the region of the anastomosis to help detect leakage and manage smaller leaks in the postoperative period. Although not classically described in the literature, in the opinion of the authors, attention should also be paid to the placement of the biliary anastomosis with respect to the pancreatic anastomosis. Whenever possible, at least 10–15 cm should be left between the two anastomoses to prevent reflux of biliary fluid into the pancreatic anastomosis. Although little clinical evidence exists to support this practice, it is an important anecdotal observation that may decrease the incidence of massive pancreatic anastomotic disruption.

Fig. 27.1

a Completed posterior row of 3-0 silk stitches. b Posterior row of 5-0 PDS duct-to-mucosa stitches and pancreatic duct stent in place. c Completed pancreaticojejunostomy

There exists some debate on the use of closed suction drains following PD. Drainage of the pancreatic anastomosis may be associated with greater likelihood of pancreatic fistula, and some have advocated abandoning the use of drains routinely following PD [14, 15]. It is the opinion of the authors that drains should be placed following most, if not all PD and clinical trials support this. A recent randomized multicenter trial comparing routine placement of operative drains to no drains following PD provides level-one evidence that routine use of closed suction drains should be standard of care. In this study, all-cause mortality was higher in the no drain group and there was an increased number and mean severity of complications when operative drains were not placed. There was no increase in the incidence of pancreatic fistula between the two groups [16]. It is likely that the excess mortality seen in the no drain group reflects the consequences of undrained pancreatic fluid in the small number of patients who develop significant compromise to the integrity of the pancreaticojejunostomy, resulting in the development of multisystem organ failure (MSOF) and death.

Despite compelling data supporting the routine use of drains, an emerging consensus also suggests that they represent a double-edged sword and can lead to an increased incidence of pancreatic fistula when left in situ for a prolonged period of time. Prospective data indicate that amylase activity of drain effluent less than 5000 U/L predicts a low likelihood of clinically significant pancreatic fistula [17]. In these patients with a low risk of pancreatic fistula, drains may be safely removed early in the postoperative period without relying on standard metrics of drainage character or volume. A prospective randomized study investigating early removal of operative closed suction drains in patients with postoperative day 1 drain that amylase values of less than 5000 U/L found significantly fewer complications, including pancreatic fistulae in the early removal group (postoperative day (POD) 3 vs. ≥ POD 5) [18]. Several caveats should be noted in this study including the fact that the authors did not use closed suction drains and subjects were only randomized if they showed “no adverse clinical metrics.”

It is the author’s opinion that closed suction drains are important in the early postoperative period to assist in management of major disruptions of the pancreatic anastomosis. However, persistent application of negative pressure can clearly lead to persistence of a “nuisance” low-grade fistula. Since 2008, we have adopted a modified “Verona” protocol: One or two #19 channeled closed suction drains are placed near the pancreatic anastomosis and drain amylase activity is measured on POD 3. For patients who are clinically improving and have drain amylase activity of less than two to three times the serum amylase on POD 4, the drain(s) is/are removed. In our experience, this approach has resulted in a very low rate of uncontrolled pancreatic leaks while also minimizing clinically insignificant “nuisance” low-grade fistulae.

Major anastomotic disruptions typically present early in the postoperative course (POD 3–5) though they may occur later, as in the case of an operative drain that has eroded tissues, thus creating an anastomotic dehiscence. Often, the first recognized indications of a major disruption of the pancreatic anastomosis will be deteriorating clinical indices such as tachycardia, hypotension, fever, and oliguria. Delayed return of bowel function and/or delayed gastric emptying is also common, though nonspecific findings. Leukocytosis/leucopenia, electrolyte abnormalities (i.e., acidemia, hypokalemia), thrombocytopenia/thrombocytosis, coagulopathy, and anemia are frequent laboratory findings. In cases of grade C fistula, patients may meet criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)/sepsis and many experience some degree of MSOF involving cardiac, respiratory, renal, hepatic, and other organ systems.

Management of major pancreatic anastomotic disruption should progress in a logical, stepwise fashion (Fig. 27.2). The two primary clinical goals in the early setting of a massive pancreatic anastomotic failure are goal-directed resuscitation to maintain end-organ perfusion and establishment of a controlled pancreatic fistula. Intravenous fluids (either crystalloid or blood, as indicated) to maintain euvolemia and correct acidosis should be administered. Adequate vascular access including central venous catheter(s), arterial catheter, and/or pulmonary artery catheter may be indicated.

Fig. 27.2

Diagnostic/therapeutic algorithm for pancreaticojejunostomy dehiscence. Single asterisk drain output: bilious, “cloudy/dishwater”, bloody; double asterisk clinical indices: tachycardia, fever, leukocytosis, abdominal pain; PD pancreaticoduodenectomy, PF pancreatic fistula, SIRS systemic inflammatory response syndrome, MSOF multisystem organ failure

In attempting to diagnose and characterize pancreatic fistulae, computed tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen have limited ability to assess the integrity of the pancreatic anastomosis and are only used to assess for the presence of undrained pancreatic fluid collections (Fig. 27.3). Patients are often acutely ill, and the decision of whether and when to transport to the radiology department should be carefully considered. Given that most patients with significant SIRS have disruptions in regional blood flow to the kidney and are at significant risk of contrast-induced nephropathy, intravenous (IV) contrast should rarely be used.

Fig. 27.3

Computed tomography scan showing pancreaticojejunostomy leak.  a – pancreatic remnant,

a – pancreatic remnant,  b – peripancreatic fluid collection,

b – peripancreatic fluid collection,  c – pancreatic duct stent

c – pancreatic duct stent

a – pancreatic remnant,

a – pancreatic remnant,  b – peripancreatic fluid collection,

b – peripancreatic fluid collection,  c – pancreatic duct stent

c – pancreatic duct stentAn attempt at nonoperative management is warranted and is successful in a vast majority of instances in the experience of the authors. For situations where a surgical drain was not placed, the patient demonstrates clinical SIRS, and a major pancreatic anastomotic disruption is suspected, an attempt at image-guided percutaneous drainage is worthwhile in all but the most unstable patients. Most patients will demonstrate significant and rapid clinical improvement with successful establishment of a controlled fistula via a percutaneous drain. In patients with existing surgically placed drains, a noncontrast CT scan can be considered to rule out displacement of the drain and/or presence of undrained collections.

Once drainage is accomplished, the character of the drain fluid should be noted: Classically, thin, cloudy, gray “dishwater” fluid is observed in situations of major disruptions. It is important to note that drain fluid from major pancreaticojejunostomy disruptions is often bilious. Bile may leak retrograde from the hepaticojejunostomy through a disruption in the pancreaticojejunostomy if it is not draining antegrade through the efferent jejunal limb. Considering that the hepaticojejunostomy is a more structurally robust anastomosis, bilious drainage can be considered the more likely result of a leaking pancreaticojejunostomy than vice versa. As was noted above in the section on constructing a pancreaticojejunostomy, this bile reflux may be more significant when there is insufficient length between the hepaticojejunostomy and pancreaticojejunostomy and, in the opinion of the authors, contributes to development of severe pancreatic fistulae.

Bloody drainage is a particularly ominous sign as this may indicate hemorrhage from a ruptured pseudoaneurysm of the gastroduodenal artery or other visceral arterial branches exposed during the course of dissection. Most cases of pseudoaneurysm rupture appear later in the course of a significant pancreatic leak, often 2–3 days after recognition of the leak when the patient has recovered from the initial insult. As with pancreatic fistula, an international study group classification of postpancreatectomy bleeding has been established (Table 27.2, 27.3) [19].

Table 27.2

International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery ( ISGPS) definition of postpancreatectomy hemorrhage. (Adapted from [19])

Definition of postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH) |

|---|

Time of onset |

Early hemorrhage (≤ 24 h after the end of the index operation) |

Late hemorrhage (> 24 h after the end of the index operation) |

Location |

Intraluminal (intraenteric, e.g., anastomotic suture line at stomach or duodenum, or pancreatic surface at anastomosis, stress ulcer, pseudoaneurysm) |

Extraluminal (extraenteric, bleeding into the abdominal cavity, e.g., from arterial or venous vessels, diffuse bleeding from resection area, anastomosis suture lines, pseudoaneurysm) |

Severity of hemorrhage |

Mild |

Small or medium volume blood loss (from drains, nasogastric tube, or on ultrasonography, decrease in hemoglobin concentration < 3 g/dL) |

Mild clinical impairment of the patient, no therapeutic consequence, or at most the need for noninvasive treatment with volume resuscitation or blood transfusions (2–3 units packed cells within 24 h of end of operation or 1–3 units if later than 24 h after operation) |

No need for re-operation or interventional angiographic embolization; endoscopic treatment of anastomotic bleeding may occur provided the other conditions apply |

Severe |

Large volume blood loss (drop of hemoglobin level by ≥ 3 g/dL) |

Clinically significant impairment (e.g., tachycardia, hypotension, oliguria, hypovolemic shock), need for blood transfusion (> 3 units of packed cells) |

Need for invasive treatment (interventional angiographic embolization, or relaparotomy) |

Table 27.3

International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery ( ISGPS) classification of postpancreatectomy hemorrhage. (Adapted from [19])

Classification of PPH: clinical condition, diagnostic, and therapeutic consequences | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Grade | Time of onset, location, severity, and clinical impact of bleeding | Clinical condition | Diagnostic consequence | Therapeutic consequence |

A | Early, intra- or extraluminal, mild | Well | Observation, blood count, US and, if necessary CT | None < div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|