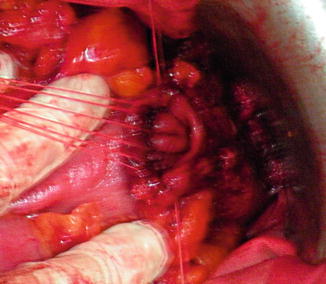

Fig. 8.1

Low tie of the inferior mesenteric artery (intraoperative aspect)

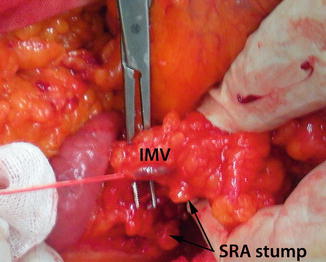

Fig. 8.2

Isolated and ligated inferior mesenteric vein (intraoperative aspect)

Regarding the vascular time of the anterior resection, there are surgeons who prefer the ligation of the inferior mesenteric vessels (vein and artery) before the mobilization of the left colon, in order to prevent mobilization of tumoral cells in portal venous system (no-touch isolation); even though after the surgery malignant cells were discovered in the portal vein blood stream, it was established that this approach (somehow more difficult and risky) does not influence the recurrence or the survival of the patients. The same conclusion is available for tumor’s isolation between ties applied above and below the tumor, in order to prevent cancerous cells distal spillage and local anastomotic recurrences. For the latter reason, a good lavage with antiseptics (povidone-iodine) of pelvis and rectal stump will be more easy and efficient than a rectal untimely mobilization in order to isolate the tumor [7, 13, 14, 18].

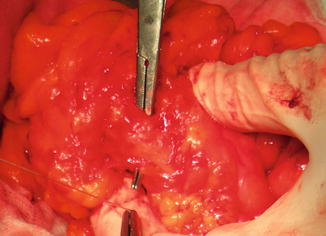

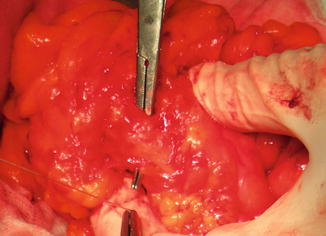

After the main vascular trunks were divided, the left colonic mesentery will be carefully sectioned not to injure the left ureter and, also, not to interrupt the marginal vascular arcade up to the level chosen for sigmoid sectioning: at the descending-sigmoid junction or, if a long, healthy, sigmoid is available, a little more distal, preserving enough length for a low anastomosis (an approximation may be made at this point, descending the remaining colon until it reaches the pubis) (Fig. 8.3). At the chosen level, the vascular marginal arcade will be ligated and divided; also, the bowel wall will be sectioned at this point (in order to avoid a septic time of the surgery from this moment on, the colon may be sectioned after the rectal dissection, but with the sectioning, the next operative movements will be much more easier) [18]. If the colon is sectioned, the upper colon will be wrapped with povidone moistened swabs and put back in the peritoneal cavity, while the resected sigmoid will be used for traction, in order to make mesorectal connections more evident with surrounding fascial and neurovascular structures.

Fig. 8.3

Sigmoid mesentery sectioning (intraoperative aspect)

Obviously, in case of cancer invasion in the anterior structures, an en bloc resection of the invaded portion must be taken into consideration, if a radical resection (R0/R1) seems probable (partial cystectomy, hysterectomy). Nowadays, such cases are usually diagnosed preoperatively, therefore these patient benefit from neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy [10, 21, 30].

From this moment on, the most delicate part of the resection begins: discovering and maintaining a correct mesorectal plane and fashioning a delicate colorectal anastomosis deep in the pelvis. The pelvic dissection commences on the posterior aspect of the resection specimen: maintaining a moderate traction on the inferior mesenteric pedicle (already sectioned) (Fig. 8.4) and the sectioned sigmoid, the dissection will continue downward on the anterior surface of the aorta, looking for the “holly,” avascular plane between the rectal fascia and presacral fascia [13, 14] (Fig. 8.5).

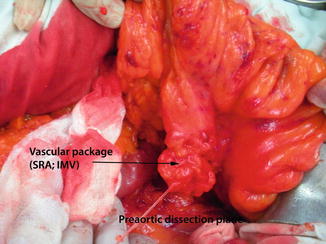

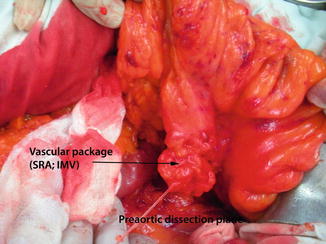

Fig. 8.4

Upper rectal vascular package prepared to enter the posterior mesorectum (intraoperative aspect)

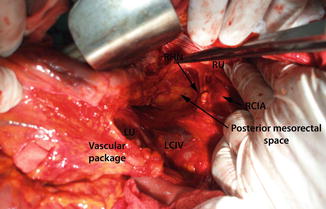

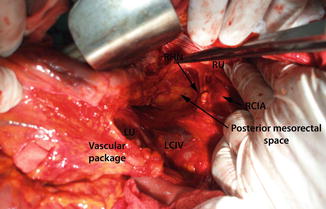

Fig. 8.5

Posterior mesorectal space dissected. The common risk on posterior dissection: LU left ureter, RU right ureter, RCIA right common iliac artery, LCIV left common iliac vein, RHN right hypogastric nerve (intraoperative aspect)

At this point, great care must be taken for two possible major risks: the risk of nervous damage (hypogastric nervous plexus, located just below the bifurcation of the aorta, and hypogastric nerve, which origins at this level and continues to both sides just under the presacral fascia); the other important risk is leaving the holly plane and entering the rectal fascia (conning in) and leaving cancerous cell deposits or even lymph nodes in the pelvis, the source of local recurrence. Leaving the correct dissection plane and entering into the presacral fascia has another risk: lesions of the presacral veins, which tend to retract into the sacral foramen, hemostasis being very difficult to be achieved in such cases.

The posterior dissection is continued as deep as possible (until the tip of coccyx) with the rectum put on tension and careful sharp sectioning (diathermy or blunt scissors), keeping under direct vision the shinny mesorectal fascia and maintaining its integrity using only sharp dissections and avoiding blunt dissection which will tear the mesorectal fascia [13, 14].

When posterior dissection reached the desired level, low rectal resection will continue on the anterior plane, less risky in women, but with much more attention in men, in which leaving the correct plane may results in damage of the seminal vesicle, prostate, bladder, or genitourinary nerves, or penetrating in the rectum, increasing the risk of local recurrence. For these reasons, the anterior dissection will commence with peritoneal folds (already sectioned) put on tension and a good retraction of the bladder, using sharp scissors, until it reaches the seminal vesicle and the prostate; at this level, the Denonvillier’s fascia will be sectioned, not too laterally to avoid damaging the nervi erigentes.

With posterior and anterior plane of dissections finished, the cylindrical mobilization of the rectum may be achieved now, by sectioning the lateral aspect of the mesorectum (lateral rectal ligaments). The lateral sectioning will be made maintaining contact with mesorectal fascia and a good tension on the rectosigmoid upward and to the opposite site of dissection, with care not to damage the ureters, or the pelvic plexus with its genitourinary nerves. On the lateral ligaments, in 15–20 % of cases, the middle rectal artery may be found, requiring careful diathermy or good isolation and ligation, in order to prevent bleeding (in case of bleeding the attempt to achieve the hemostasis increases the risk of autonomic pelvic plexus damage).

Obviously, a tumor extended beyond the mesorectal fascia will impose leaving this plane and removing all the surrounding tissue, regardless of the nerve damage, in order to ensure a good local clearance and prevent recurrence; still, in these advanced cases, a local recurrence is to be expected.

The level of rectal and surrounding mesorectum sectioning depends mainly on the level of the tumor; it is commonly agreed that mid-rectal and distal rectal cancer will impose total mesorectal excision, with sectioning of the rectal wall at least 2 cm below the macroscopic lower edge of the tumor (a much lower level of sectioning is recommended in case of an undifferentiated rectal cancer). For higher rectal cancers, it has been proved that total mesorectal excision is unnecessary, a level of the rectal and mesorectal sectioning located 5 cm below the tumor being sufficient (usually there are not cancerous mesorectal deposits beyond this limit) [15, 18, 21].

The distal limit of resection is, therefore, different, depending on the tumor topography: easier to be achieved in upper rectal cancer, but more difficult in case of a middle or lower rectal cancer. For the latter, there are two modalities of sectioning the mesorectum and rectal wall: in the Heald’s vision, the posterior mesorectum will be removed from the pelvic wall until the anorectal angle, then it is removed back from the rectal muscle tube, leaving a 1–2 cm posterior rectal wall with a possible deficiency in the vascular supply, explaining the higher incidence of anastomotic dehiscence in this approach. The other possibility is to section the mesorectum and rectal wall at the lowest level of the mesorectum (2–3 cm above the dentate line) in all middle and lower rectal cancers [18, 21]. In case of a too lower tumor, the sectioning plane may be lowered to the intersphincteric plane (ultralow rectal resection).

After the distal desired limit of the dissection has been reached, the rectum will be transected (with scissors or transverse stapler) (Figs. 8.6 and 8.7). The resection specimen will be examined carefully to the distal resection limit (Fig. 8.8): a too close distal margin or even invaded distal margin will require a re-resection (usually it means transforming anterior resection into an abdominoperineal resection), but the postoperative results may be compromised due to the risk of local recurrence (intraoperative contamination and inadequate circumferential margin).

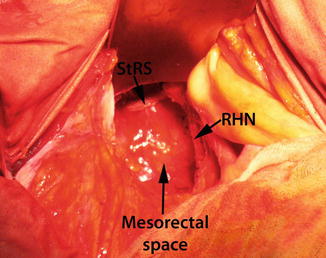

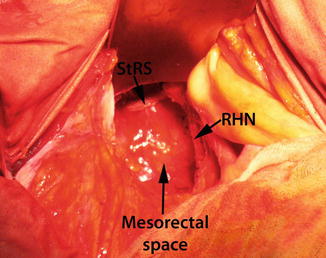

Fig. 8.6

Stapled rectal stump (StRS) and mesorectal postresectional space (RHN right hypogastric nerve) (intraoperative aspect)

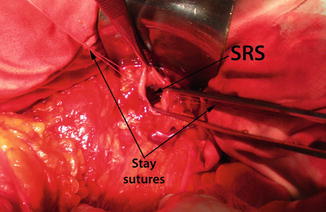

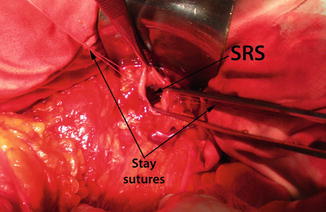

Fig. 8.7

Rectal stump sectioned (SRS) and prepared for hand-sutured anastomosis (intraoperative aspect)

Fig. 8.8

Two centimeters safe distal margin in an anterior rectal resection specimen

Anastomosis

It is now the delicate moment of confectioning a colorectal anastomosis deep in the pelvis; the degree of difficulty is variable with respect to the local conformation: much easier in women (but not always), the difficulty increases in men with a deep and narrow pelvis. Before the anastomosis confectioning starts, a second control on mobilized colon length and, especially, on its quality of vascularization, is mandatory; if the length appears to be insufficient, a large mobilization may be performed, in order to avoid a tensioned anastomosis, by sectioning the gastrocolic ligament, but, in case of compromised vascularization, a re-resection (along with supplementary mobilization) is mandatory to be performed, in order to ensure a very good arterial blood supply and venous drainage of the anastomotic colon (arterial pulsation of the vasa recta in the vicinity of the section level, arterial bleeding from the sectioned colon, normal color of the bowel wall).

The anastomosis itself may be performed manually (hand-sutured anastomosis) or with a circular stapler; although there are several reports over an increase incidence in leakages and even local recurrence rate after stapled-anastomosis, no statistical significance has been reached, and, on the other hand, this conclusion may be affected by the conditions in which the anastomosis was performed: usually, a stapled anastomosis (Figs. 8.9 and 8.10) will be constructed in difficult conditions, hand-suture anastomosis being much more difficult in a narrow pelvis with a low rectal resection [4, 34].

Fig. 8.9

The rectal and colonic stumps prepared for circular stapling (intraoperative aspect)

Fig. 8.10

Stapled anastomosis (final aspect)

Although considered possible, hand-sutured anastomosis (Figs. 8.11 and 8.12) will be much more difficult to be performed in low resections, especially in a narrow pelvis, therefore, in order to increase the number of sphincter-preserving resections, a stapler must be available when starting a presumed anterior resection; also, the initial positioning of the patient must allow a good access to the anal canal, regardless the type of anastomosis intended to be done. Of a greater importance is avoiding the rectal stump to retract after sectioning; for this reason, stay sutures or an L-shape clamp must be applied before rectal sectioning. The problem of the rectal stump remains even in case of an anticipated stapled anastomosis: in a narrow pelvis it will be difficult to insert a TA-stapler in order to transect the distal rectum, and also a purse-string suture may be very difficult to be performed. The modified double-stapling technique may be useful [27], but in a very low resection and great difficulty in performing the purse-string suture (even transanally in some cases!), a hand-sutured coloanal anastomosis may be preferable to a high risk colorectal anastomosis. Of course, in such difficult cases, a protective stoma is mandatory to be performed [21].