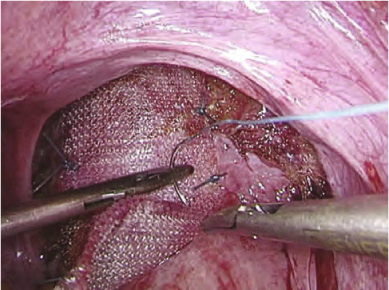

Fig. 21.1

The ventral position of the mesh allows correction of rectorectal intussusception, reinforcement of the rectovaginal septum and performance of a colpopexy. Closure of the peritoneum above the mesh elevates the pouch of Douglas

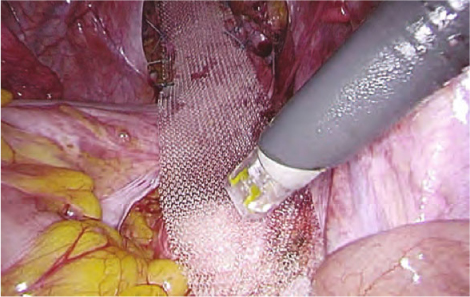

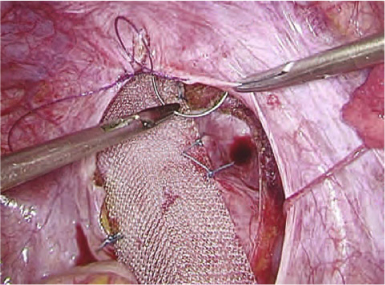

Fig. 21.2

The strip of polypropylene is sutured to the anterior aspect of the rectum

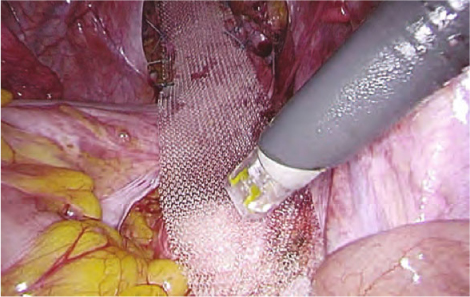

The mesh is then fixed to the sacral promontory using an endoscopic “tacker” device (Endopath EMS; Ethicon Endo-surgery, Norderstedt, Germany) (Fig. 21.3), and secured with one stitch of Ethibond 2.0. No traction is exerted on the rectum, but the prolapse should be reduced at the time of mesh fixation. The rectum remains in the sacrococcygeal hollow. The surgeon should take care not to strangle the rectosigmoid between the sacral promontory and the mesh.

Fig. 21.3

Proximal fixation of the mesh to the sacral promontory using a stapler device

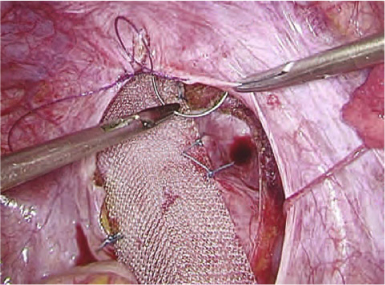

21.2.5 Colpopexy and Peritoneal Closure

The posterior vaginal apex (vaginal vault) is then identified and elevated by a vaginal trainer and sutured to same strip of mesh. Two lateral sutures incorporate the (remainder of the) uterosacral ligament. If an enterocele is present, more sutures must be made. Ideally, the sutures should not perforate the vaginal wall. This maneuver allows closure of the rectovaginal septum and suspension of the middle pelvic compartment. In this way, a vaginal vault prolapse or enterocele is corrected.

The lateral borders are closed over the mesh using the V-Loc 90 absorbable wound closure device (Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts, USA) elevating the pouch of Douglas over the colpopexy (and creating a neo-Douglas) (Fig. 21.4). This maneuver is important to avoid any later small-bowel entrapment and/or erosion.

Fig. 21.4

The lateral borders of the peritoneum are closed over the mesh elevating the neo-Douglas over the colpopexy

No peritoneal drain is left in place. Ports are removed in a routine fashion, and only the fascia at the 12 mm port is closed.

21.2.6 Perineotomy (Facultative)

It can be difficult to complete the rectovaginal septum dissection to the level of the pelvic floor. This maneuver is important in treating a complex, supra-anal rectocele. In this specific situation, the surgeon can decide to complete the laparoscopic dissection with a small perineotomy. The incision is made immediately dorsal to the vaginal orifice to open the perineal body. Dissection should be meticulous to avoid any perforation of the vagina or rectum. After perineotomy, this dissection joins the laparoscopic dissection plane, allowing mesh fixation in the deepest part of the rectovaginal septum and restoring the perineal body. However, a perineotomy can be avoided in most patients with a total rectal prolapse and should only be performed when laparoscopic dissection at the level of the perineal body fails.

21.2.7 Postoperative Treatment

The patient can resume oral intake the day of surgery. A fiber-enriched diet is prescribed. The urinary catheter is removed the following day, and mobilization is started. According to clinical progress, the patient can be discharged from day 1 onwards. Straining efforts and heavy lifting are discouraged for 4–6 weeks after surgery.

21.3 Outcome after LVR

From January 1999 to December 2008, 405 patients underwent LVR for rectal prolapse syndromes. The mean age was 54.6 years [standard deviation (SD) 15.2] and median age was 55 years (range 16–88). Most patients were women (n = 376, 93%). Of the 405 patients, 168 (41.5%) had undergone previous pelvic surgery, the most common of which was hysterectomy in 154 patients (39%) (Table 21.1). In 27 patients (6.8%), LVR was performed for recurrent rectal prolapse.

Table 21.1

Previous pelvic surgery in 168 patients who underwent laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for rectal prolapse syndromes

Procedure | n (%) |

|---|---|

Hysterectomy | 154 (39.1) |

Cystopexy | 36 (9.1) |

Rectopexy | 19 (4.8) |

Delorme/Altemeier | 8 (2.0) |

Cesarian section | 15 (3.8) |

Sphincter repair | 4 (1.0) |

Gynecological procedure | 4 (1.0) |

Colectomy | 3 (0.8) |

Kidney transplantation | 1 (0.3) |

Prostatectomy | 1 (0.3) |

Total | 168 (41.5) |

Most of the patients had an internal rectal prolapse (45.9%, n = 186). Other indications were total rectal prolapse (43%, n = 174) and isolated rectocele and/or enterocele (11.1%, n = 45). In 95 of the patients (23.5%) the laparoscopic dissection of the rectovaginal septum was completed with a small perineotomy to treat a complex supra-anal rectocele, as previously described [13].

Data concerning operative difficulties and conversion, postoperative morbidity, and recurrence were gathered from a prospective database. Postoperative complications were graded according to Clavien-Dindo [14, 15]. The mean follow-up was 25.3 months (SD ±30, range 6–143). An extensive institutional questionnaire that assessed symptoms of anorectal and sexual dysfunction was used.

Data are presented as mean and SD, median and range. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for nonparametric paired data and a t test for paired and unpaired samples. p < 0.050 was considered statistically significant.

21.3.1 Conversions

Conversion to laparotomy was required in eight patients (2%). Five patients underwent conversion because of adhesions as a result of multiple abdominal operations. In three patients, acute bleeding from the left iliac vein occurred, requiring urgent laparotomy to obtain hemostasis. All underwent open ventral rectopexy. There were no other intraoperative complications and no blood transfusion was required.

21.3.2 Morbidity

Perioperative mortality did not occur. Morbidity was noted in 74 patients (18%), but it was minor (grade I and II complications) in the majority of patients: urinary tract infection in 23 patients (5.9%), superficial wound dehiscence in 18 patients (4.6%), prolonged ileus treated conservatively in 12 patients (3.1%), and postoperative hematoma or bleeding in nine patients (2.3%) (Table 21.2). Six patients (1.5%) underwent a re-intervention under general anesthesia within 30 days after surgery (grade III complications, Table 21.3).

Table 21.2

Grade I and II complications

Complication | n (%) |

|---|---|

Urinary tract infection | 23 (5.9) |

Superficial wound dehiscence

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|