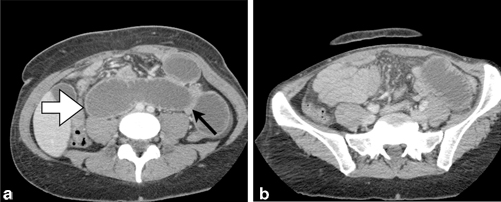

Fig. 11.1

Benign pneumatosis intestinalis around a jejunostomy tube. a and b Abdominal CT scan (soft tissue and lung windows); arrow points to loop of jejunum with pneumatosis (jejunostomy tube in that bowel loop is not visualized on these images). c and d Five days later the degree of pneumatosis has decreased considerably

Bowel Obstruction

While ileus may result from any intraabdominal operation, bowel obstruction is a complication that may require more aggressive intervention or reoperation. The entry site of the feeding tube into the bowel lumen is a potential site of obstruction. A Witzel jejunostomy that gathers up too much seromuscular tunnel will result in decreased cross-sectional area at that site. Tube feeding may be tolerated, as the tip of the tube is distal to the site of bowel narrowing, but the patient may have vomiting, conduit distention, or increased nasogastric tube output as the bowel transit upstream of the Witzel tunnel is impeded. A recent report on 153 patients who underwent a Witzel jejunostomy tube noted a 7 % incidence of bowel obstruction [40]. However, this publication suffers from a lack of definition of obstruction, and no mention was made of whether these patients necessitated intervention beyond bowel rest for this condition. In addition, it is unclear what the duration of follow-up is. Far more prevalent in the literature are reports that detail minimal or no episodes of bowel obstruction in the short-term, which reflects avoidance of technical error during the placement of the feeding tube [9, 41, 42].

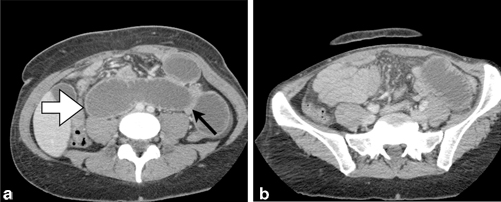

Volvulus around the jejunostomy tube or through an internal hernia has been described as etiologies of bowel obstruction [43, 44] (Fig. 11.2). Despite the single-tacking site of percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy or direct percutaneous jejunostomy tubes placed with fluoroscopic or ultrasound guidance, the reporting of volvulus with those techniques is still quite rare [45–47]. Other obstructive events include obstruction from the catheter balloon, which may be obviated by choice of tube or avoidance of balloon over-inflation [48]. Intussusception at the site of direct percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy tubes has been described by multiple groups [49–51]. Despite the usual technique of multiple tacking sites with a Witzel jejunostomy tube, it has been described with that technique as well [52].

Fig. 11.2

Small bowel obstruction secondary to internal herniation and volvulus around jejunostomy tube site. a Abdominal CT depicting dilated loops of small bowel ( white arrow) as well as a decompressed loop of small bowel tacking along the previous jejunostomy tube site ( black arrow). b Decompressed small bowel in the right lower quadrant; dilated loop of small bowel in the left lower quadrant

In cases of obstruction, an exploratory laparotomy or laparoscopy may be employed. A partial obstruction may be observed at times. Edema at the Witzel tunnel may reduce in time with conservative measures and allow free passage of enteric contents. If there is a balloon catheter responsible for the obstruction, this may be diagnosed with contrast studies or simple examination of the tube and balloon apparatus and remediated by balloon deflation.

Tube Dysfunction

Overall rates of tube dysfunction have been reported as high as 45 % in a mixed series of gastrostomy and jejunostomy tubes. These complications—clogging, knotting of the tube [53], dislodgement, or breakage of the connectors—may be considered minor; however, they may lead to the interruption of nutrition delivery or additional invasive procedures. Clogging of the tube is a very common problem, reported in 0.5–6 % of prospectively collected series of patients undergoing a Witzel jejunostomy tube at the time of esophagectomy or gastric surgery [41, 54]. Needle catheter jejunostomy has been reported to have similar propensity for clogging as Witzel jejunostomy [55]. Best practices for feeding tube maintenance include adherence to a flushing regimen and avoidance of introducing any solid material into the tube (e.g., crushed pills). In addition, checking of residuals via a jejunostomy tube is not recommended, both due to technical limitations and inaccuracy of the measurement and due to concerns that this might hasten clogging. Meat tenderizer, pancreatic enzymes, and soda have all been utilized to help dissolve the inspissated tube feed substance from clogged jejunostomy tubes [56]. Of these agents, pancreatic enzyme appears to have the greatest efficacy in resolving the obstruction, with 96 % restoration of tube patency in one series [57]. Some researchers have suggested that a pancreatic enzyme “lock” similar to a heparin lock for vascular catheters may be utilized as prophylaxis against inspissated tube feeds obstructing the feeding tube [58]. The mechanical remedy for a clogged tube is steady or oscillating pressure via a syringe filled with saline or water. Reconstitution of patency has also been achieved with a vascular embolectomy catheter [59]. Of note, in the series quoted above with a 6 % incidence of tube obstruction, all feeding tubes were able to be recanalized with local measures, without need for replacement of the tube [41].

Similar to any externalized tube or drain, jejunostomy tubes are subject to dislodgement. While this data point may be under-reported in the largely retrospective reviews of jejunostomy tube complication (as simple replacement of the tube may occur without any documentation), a prospective trial of nasoduodenal tubes versus jejunostomy tubes reported a 6 % incidence of tube dislodgement [7]. Dislodgement of jejunostomy tubes that required a reoperation to address the problem occurred in 1.2 % of patients in another series [54]. In one particularly notable case report, a patient with a jejunostomy tube that had been placed for enteral access in the setting of unresectable gastric cancer presented with “disappearance of the tube and abdominal pain” and was found to have the entirety of the tube within the bowel [60]. Peristalsis eventually allowed the tube to pass per rectum without any surgical intervention.

For chronically indwelling surgically placed tubes, the tract may not close completely for 2–3 days, though the optimal timing for direct replacement of a jejunostomy tube is as soon as possible after it falls out. If there is an undue resistance in passing a lubricated tube of the same size as that which was dislodged, the procedure should be aborted. A contrast study via the tube should confirm a correct placement prior to use.

If a surgical tract is no longer directly accessible, ultrasound or fluoroscopy may facilitate tube replacement at the site of the previously tacked jejunum. In one series, successful jejunostomy tube replacement at the site of a previous surgical jejunostomy was achieved in 26 of 28 attempts (92 %) [61]. While the mean time from surgical jejunostomy tube removal to direct percutaneous placement averaged 278 days, the range included sites as early as 3 days from removal. Some surgeons will mark the tube entry site into the bowel with metallic clips to facilitate direct fluoroscopic-assisted percutaneous access if necessary [62]. However, as a caveat, metal clips may not always correspond to the exact site of accessible bowel over time [63].

To help mitigate accidental tube dislodgement, the device or sutures used to secure the tube to the abdominal skin should be inspected routinely and replaced as necessary.

Infectious Complications

In a prospective trial, leakage around a feeding tube was detected in 4 %, though only one patient of 79 ended up needing a re-laparotomy for complication [7]. (Fig. 11.3) Often, a small amount of succus entericus may stain the dressing around the jejunostomy tube. When this occurs in notable amounts, local measures may be employed to keep the skin from becoming excoriated. Vigilance for signs of superficial or deeper infection must be maintained.

Fig. 11.3

Abdominal wall abscess secondary to leaking of succus entericus and tube feeds around jejunostomy tube. Arrow points to jejunostomy tube

Infection at the tube entry site occurred in 0.5 % of patients in a series of over 400 patients undergoing a Witzel jejunostomy tube [54]. In Han-Geurts’s report of a randomized trial of needle catheter jejunostomy versus nasoduodenal tubes, the rate of site infection was 16 % [7]. With direct percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy tubes, a 6 % site infection rate has been reported, with all of these being treated successfully with antibiotics alone [45]. In this same series, a single patient (0.6 % incidence) did suffer an abdominal wall abscess in the setting of peri-tube leakage; this required operative debridement. Occasionally, with minor cellulitis and no significant abscess collection, opening the tract more widely around the tube and passing a wick into the space may help. Occasionally, the leakage associated with the infection is too persistent and re-siting or upsizing of the tube may be necessary. Necrotizing fasciitis is a rare sequela of a tube infection, but has been described in percutaneous and surgical jejunostomy tubes alike [64, 65].

Aspiration

The rate of aspiration events with jejunostomy tube feeding is a controversial subject. Many groups believe that there is a decreased rate of aspiration with jejunostomy tubes as compared with gastrostomy tube feeding [66, 67]. In the early experience with percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy tubes, a very high aspiration rate (67 %) was reported [68]. However, more mature results from the same group were more promising, with the mean number of aspiration pneumonia events per month decreasing from 3.39 to 0.42 after the placement of the percutaneous jejunostomy tube [69].

In a counter-argument, one group reported no difference in the rate of aspiration pneumonia with surgically placed gastrostomy and jejunostomy tubes [70]. Moreover, a prospective randomized trial of nasally placed gastric or jejunal tubes demonstrated no difference in the aspiration rate [71]. Jejunal tube feed infusion itself was detected to induce gastroesophageal reflux, even in the absence of gastric distention [72].

The key point around the issues of aspiration is to individualize the treatment to the patient. For example, some patient populations (e.g., elderly stroke patients) laparoscopic enteral access may not obliterate the risks of aspiration and pneumonia, and their overall mortality rate may be quite high [73]. The same might be taken into account in the elderly aspirating population, where jejunostomy feeding in and of itself does not protect against aspiration pneumonia in patients known to aspirate [74].

Conclusion

Jejunostomy tube feeding remains an important adjunct to major esophageal surgery. While it may not be necessary to perform a jejunostomy tube in every case as nutritional support may be able to proceed uneventfully by mouth, the reasonably low rate of complication and the ease of discontinuation of the tube argue that prophylactic placement is a valid strategy. Complications of jejunostomy tubes may be reduced with careful attention to the technical details of surgical placement. In addition, early signs of complication must be followed closely so that salvage might occur should a highly morbid process begin to unfold.

Key Points

1.

Jejunostomy tubes are often placed at the time of esophagectomy and/or gastrectomy in order to optimize nutritional status. Their utility is debated.

2.

Jejunostomy tubes can be placed surgically with three different techniques: Stamm, Witzel, or needle-catheter. Endoscopic and percutaneous techniques can be utilized on a selective basis as well.

3.

Complications after jejunostomy tube placement include bowel necrosis and perforation, obstruction, volvulus, tube-feeding intolerance, infection, aspiration, and tube dysfunction. Careful attention to the technical details of tube placement and tube choice are needed to minimize these complications.

4.

Technical pearls include avoiding obstruction of the bowel lumen with either too large of a tube size or over-zealous imbrication while performing a Witzel technique. Broad-based fixation of the bowel to the abdominal wall should be employed to avoid obstruction and volvulus.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Ligthart-Melis GC, Weijs PJ, te Boveldt ND, Buskermolen S, Earthman CP, Verheul HM, et al. Dietician-delivered intensive nutritional support is associated with a decrease in severe postoperative complications after surgery in patients with esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26(6):587–93. PubMed PMID: 23237356.CrossRefPubMed

6.

7.

Han-Geurts IJ, Hop WC, Verhoef C Tran KT, Tilanus HW. Randomized clinical trial comparing feeding jejunostomy with nasoduodenal tube placement in patients undergoing oesophagectomy. Br J Surg. 2007;94(1):31–5. PubMed PMID: 17117432.CrossRefPubMed

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree