The prevalence of IBS is reported to remain relatively stable over short periods of time [11, 25, 26], with the reso-lution of symptoms in some individuals matched by the onset of new symptoms in others. However, individuals readily change their subgroup, as defined by predominant stool pattern [27]. Over longer time-frames an increase in prevalence of IBS has been reported after 7 and 10 years of follow-up [28, 29]. The incidence of IBS is poorly reported. In a longitudinal study conducted in Sweden the three-month incidence was 0.2% [25]. A medical records review of a random sample of residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, estimated that the incidence of clinically diagnosed IBS was 2 per 1000 adults per year [30]. Since many people with IBS do not seek health care, the true incidence may well be higher. In a more recent study, conducted in almost 4000 individuals from a UK population based sample, the incidence was 1.5% per year during a 10-year period of follow-up [29].

Irritable bowel syndrome and health services

Individuals with IBS are more likely to consume health care resources than those without GI symptoms [31 ]. Up to 80% of sufferers may consult their primary care physician as a result of symptoms [32, 33]. Factors that drive this choice are poorly understood, but symptom frequency and severity, fear of serious underlying illness, poor quality of life, and other coexisting functional GI diseases have all been shown to predict consultation behaviour [13–15, 32–35]. It has been estimated that IBS accounts for at least 3% of all consultations in primary care [35]. Of those who do consult a primary care physician, the majority are diagnosed and managed in primary care [36], but a significant proportion will be referred for a specialist opinion at some point [9,10,15,33,35].

The condition accounts for up to 25% of a gastroenterolo-gist’s time in the outpatient department [37], and medical treatment is considered to be unsatisfactory, with patients with IBS representing a significant financial burden to health services. Despite the recommendations made by various medical organisations for a diagnosis of IBS to be made on clinical grounds alone [38–41], rather than following attempts to exclude all possible organic pathology by exhaustive investigation, many patients with symptoms suggestive of IBS will undergo colonic investigation, performed presumably in an attempt to reassure both the patient and the physician due to the potential uncertainty that may surround the diagnosis [42], or incur other medical costs [31, 35]. The annual cost of drug therapy for IBS has been estimated at $80 million in the USA [43]. In addition, patients with IBS are more likely to undergo unnecessary surgical procedures, with cholecystectomy, appendicectomy and hysterectomy rates two to three-fold higher than those observed in controls without IBS [44].

A recent systematic review of 18 studies from the UK and USA examined direct and indirect costs to the health service arising from IBS [45]. The authors estimated that IBS accounted for direct costs of between $348 and $8750 per patient per year, indirect costs of between $355 and $3344 per patient per year, and between 8.5 and 21.6 days of IBS-related sickness absence per patient per year.

Pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome

There is no known structural, anatomical, or physiological abnormality that accounts for the symptoms that IBS suf-ferers experience, and it seems unlikely that a single unifying mechanism explains them. It is more plausible that a combination of factors contributes to the abdominal pain and disturbance in bowel habit. Several proposed etiologies are discussed below.

Evidence for genetic susceptibility

Irritable bowel syndrome aggregates within families. Relatives of a patient with IBS are almost three times more likely to report symptoms compatible with IBS than relatives of the patient’s spouse [46]. Whether this is due to genetic susceptibility, shared childhood environment, or learned illness-behaviour is unclear. Twin studies demonstrate that there is a greater concordance of IBS in monozy-gotic versus dizygotic twins [47, 48]. However, having a parent with IBS was a stronger predictor than having a twin with IBS [48]. There is also evidence that children with a parent with IBS are more likely to report GI symptoms and have GI symptom-related absence from school [49]. There have been studies of various candidate genes [50, 51], but the results are conflicting, and their clinical significance is debatable.

Evidence for disturbed gastrointestinal motility

Disturbances in GI motility are thought to play a role in IBS. Previous studies have demonstrated evidence of delayed gastric emptying [52], abnormalities in small bowel and colonic transit time [53], and an increase in colonic motility in response to meal ingestion in IBS [54]. However, these abnormalities are not always reproducible, cannot be used to aid diagnosis, and vary from patient to patient. Some of this variability may be related to the predominant stool pattern experienced by the patient, but as this pattern does not exhibit great stability during follow-up [27], it is conceivable that the disturbances themselves change with time.

Evidence for visceral hypersensitivity and abnormalities of central pain processing

Abdominal pain in IBS is proposed to be related to visceral hypersensitivity, due to abnormal sensitisation of the peripheral and central nervous system. The cause of this sensitisation is unknown, but IBS sufferers report lower thresholds of pain during colonic, rectal and foregut stimulation [55, 56], with radiation to extra-abdominal sites. In addition, patients demonstrate enhanced activation of regions in the brain that are required for central pain processing in functional magnetic resonance imaging studies conducted during gut stimulation compared to controls [57,58].

Evidence for a post-infectious etiology and altered gut flora

There are numerous studies reporting an increase in symptoms that meet diagnostic criteria for IBS in individuals who have been exposed to an acute gastroenteritis of either bacterial or viral origin [59–61]. The development of post-infective IBS in one study was more likely to occur with younger age, female gender, and certain features of the initial acute illness, including bloody stools, abdominal pain and prolonged diarrhea [59]. Biopsies from the colon and terminal ileum of patients with post-infectious IBS demonstrate an increased inflammatory cell infiltrate [62], and when intestinal permeability is measured in these subjects it is increased compared to that of healthy individuals [63], which may allow luminal gut bacteria to activate an immune response in the GI mucosa, thereby leading to chronic low-grade inflammation in a subset [64].

The existence of post-infectious IBS has led to an increased interest in possible abnormalities in gut flora as a cause for the condition. Some investigators have reported altered gut flora in subjects with IBS compared to healthy controls [65], and others have reported a higher prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in IBS patients than controls, as demonstrated by lactulose and glucose hydrogen breath testing [66, 67], as well as an improvement in symptoms after therapy with non-absorbable antibiotics [68].

Making a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome

The assessment of a patient with suspected IBS should begin with a structured history to assess whether the individual’s symptoms are compatible with the diagnosis. In a patient presenting with lower GI symptoms it is important to elicit the presence of alarm (red flag) symptoms such as weight loss, diarrhea and rectal bleeding as, if these are present, they are thought to predict colorectal cancer and therefore require urgent lower GI investigation, though their diagnostic utility in this situation is suboptimal [69]. Physical examination, including digital rectal examination, is unlikely to confirm the diagnosis of IBS, but should be conducted in order to exclude other organic causes of lower GI symptoms and, if normal, may reassure both the physician and patient.

Utility of a physician’s diagnosis

As all the current available symptom-based diagnostic criteria for IBS have been developed by gastroenterologists in secondary or tertiary care, their generalisability to patients presenting to a primary care physician is debatable. A con-sensus panel reported that existing criteria were insufficiently broad for use in primary care [70], and a recent survey demonstrated that few physicians in primary care were familiar with these criteria, or used them to make a diagnosis of IBS, yet could still diagnose the condition with confidence using a pragmatic approach [71]. Guidelines for the management of IBS in primary care still advocate the use of diagnostic criteria [40, 72]. Unfortunately, there are no published studies reporting on the utility of a physician’s opinion in making a diagnosis of IBS.

Utility of individual lower gastrointestinal symptoms

The prevalence of symptoms such as lower abdominal pain, mucus per rectum, incomplete evacuation, looser or more frequent stools at the onset of abdominal pain, patient-reported visible distension and pain relieved by defecation has been reported in individuals with IBS compared to individuals without the syndrome [2–3,73–76]. Unfortunately, nocturnal diarrhea, a symptom that is often used by physicians when taking a clinical history, as an indicator of organic disease, was not studied. Since none of the other lower GI symptoms has good sensitivity or specificity for making the diagnosis of IBS [77], combinations of symptoms, in the form of symptom based diagnostic criteria, have been recommended as a means of reaching a clinical diagnosis.

Utility of symptom based diagnostic criteria

Utility of the Manning criteria

The Manning criteria have been validated prospectively in three subsequent studies since their original description in 1978 [75, 76, 78]. Therefore in total they have been validated in over 500 patients. They performed best in the original validation study [2], but also performed well in a study conducted in secondary care in Turkey [78]. However, they performed poorly in the two other studies in India [76] and Korea [75]. A recent systematic review of pooled data from these four studies assessed the utility of the Manning criteria in predicting a diagnosis of IBS [77]. The presence of three or more of the Manning criteria appeared to increase the likelihood of IBS almost three-fold, while if only two or fewer criteria were present the likelihood of the diagnosis was reduced by over 70%.

Utility of the Kruis scoring system

The utility of the Kruis scoring system has also been examined prospectively in three studies published since the original report in 1984 [73, 78, 79]. When data were pooled from all four studies [77], containing almost 1200 patients, a Kruis score of 44 or more increased the likelihood of IBS eight-fold, whilst a score less than 44 reduced the likeli-hood of the diagnosis by 70%. Whilst the Kruis score appears to have good utility in confirming a diagnosis of IBS, it is probably too complex to be used in routine clinical practice. In addition, one of the items it collects, “a history pathognomonic for any diagnosis other than IBS”, and the fact that symptom duration is required to be in excess of two years, probably account for its higher utility than the Manning criteria, which do not require minimum symptom duration.

Utility of the Rome criteria

Only one study has validated the Rome I criteria in a tertiary care setting in the UK [80]. The Rome I criteria had a sensitivity of 71%, a specificity of 85%, and their presence in a patient made a diagnosis of IBS four times more likely [77]. The Rome III criteria were validated in questionnaire form prior to their publication in two studies, using a group of patients with functional GI disorders as well as population controls, and were reported to have sensitivity of 71% and specificity of 88% for the diagnosis of IBS, as well as good test-retest reliability [81]. However, there have been no published studies that have validated either the Rome II or Rome III criteria prospectively, so their utility is relatively unknown. Given that the Rome I criteria were first described almost 20 years ago, and the Rome II criteria 10 years ago, the lack of validation is disappointing, particularly as these have become the gold standard, in research terms, for making a clinical diagnosis of IBS.

Role of investigations in excluding organic disease in patients meeting diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome

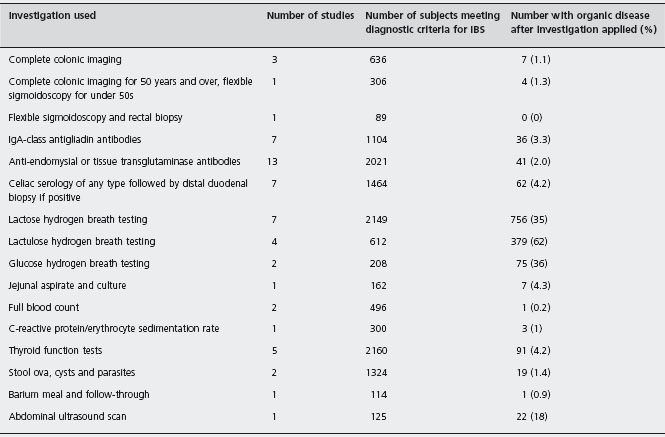

Patients with IBS may have a degree of symptom overlap with individuals with organic diseases. Thyroid disease, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, microscopic colitis, lactose intolerance, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and even colorectal cancer, in the absence of alarm symptoms, may all present with similar symptoms. As we have discussed, current diagnostic criteria are not infallible, so there may be some value to performing a limited number of clinical investigations in individuals with suspected IBS in order to exclude organic diseases that may present in a similar manner. There have been numerous studies conducted in subjects meeting diagnostic criteria for IBS that have examined the role of applying various diagnostic tests, and which report the prevalence of organic disease in these individuals (Table 21.2). The available evidence is summarized below.

Role of lower gastrointestinal investigations in irritable bowel syndrome

Five studies have reported findings following lower GI investigation in patients with IBS defined according to various diagnostic criteria [79, 82–85]. Three of these utilized complete colonic investigation in over 600 patients, two with either full colonoscopy, or barium enema in combination with flexible sigmoidoscopy [83,85], and one with either full colonoscopy or barium enema alone [79]. Only seven patients (1.1%) had an organic explanation for their symptoms, such as inflammatory bowel disease or colorectal cancer, after complete colonic investigation. One study used complete colonic investigation in patients aged over 50, and flexible sigmoidoscopy alone in the under 50s [84]. The study included 306 patients with IBS, according to the Rome I criteria, and only four (1.3%) had organic disease after investigation. Finally, one study used flexible sigmoidoscopy with routine rectal biopsy in 89 IBS patients [82]. None of these patients had organic disease diagnosed following this. This observation is in contrast to a series of patients diagnosed with microscopic colitis between 1985 and 2001 from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 40% to 55% of whom reported symptoms that met the Rome or Manning criteria, and one-third had been previously labeled as having IBS [86]. It appears, therefore, that colonic investigation has a very low yield in patients presenting with symptoms that are highly suggestive of IBS in the absence of alarm features.

Role of celiac antibodies and distal duodenal biopsy in irritable bowel syndrome

Several case-control studies have examined the role of testing for celiac disease in patients meeting diagnostic criteria for IBS, but the results are conflicting. Studies from the UK and Iran have demonstrated an increased prevalence of positive celiac serology and biopsy-proven celiac disease in individuals with IBS [87–89], as defined using the Rome II criteria, compared to controls, but data from studies conducted in the USA and Turkey do not support this association [90–92]. Of the available current guidelines for the management of IBS, only those from the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence in the UK, which are written from a primary care perspective, recommend routinely screening for celiac disease, using serology, in patients with suspected IBS [40].

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis has examined this issue [93]. Pooled prevalence of positive IgA-class anti-gliadin antibodies was 4% in subjects meeting diagnostic criteria for IBS in seven studies. Six were case-control studies, and the odds of a positive test in cases was threefold that of controls. Pooled prevalence of positive anti-endomysial antibodies or tissue transglutaminase was 1.6% in subjects meeting diagnostic criteria for IBS in 13 studies. Seven of these were case-control studies, with an odds ratio of almost 3 for a positive test in those meeting diagnostic criteria for IBS. The pooled prevalence of biopsy-proven celiac disease, following positive serology of any type, was 4% in seven studies. Five of these were case-control studies, and the odds of biopsy-proven celiac disease in cases meeting diagnostic criteria for IBS was over four-fold that of controls. The odds of biopsy-proven celiac disease were not significantly different in those with constipation-predominant, diarrhea-predominant, or mixed bowel pattern, suggesting that screening for celiac disease should not be reserved for individuals with diarrhea-predominant IBS.

Table 21.2 Yield of investigations in subjects meeting diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome.

The pooled prevalence of biopsy-proven celiac disease in individuals meeting diagnostic criteria for IBS was estimated to be between 2% and 7% [93]. The true prevalence may be higher in these studies for several reasons. First, only individuals with positive serology were offered duodenal biopsy. Second, studies did not screen these individuals for IgA deficiency, which can lead to false negative serological tests. Third, a recent report has demonstrated that the sensitivity of serology is substantially lower in individuals who do not have total villous atrophy on duodenal biopsy [94]. Economic modelling studies suggest that if the prevalence of celiac disease in subjects meeting diagnostic criteria for IBS were between 5% and 8% then screen-ing using serology, with duodenal biopsy for those testing positive, could be cost-effective depending on the willingness to pay, with a cost per quality adjusted life year gained of $5000 [95, 96]. These data indicate that testing for celiac disease in patients with suspected IBS may be a worthwhile strategy.

Role of testing for lactose intolerance in irritable bowel syndrome

Seven studies have screened IBS patients for lactose intolerance using lactose hydrogen breath testing [83, 84, 97–101]. Two studies conducted in Italy reported a prevalence of lactose intolerance in excess of 60% among those meeting diagnostic criteria for IBS [ 97, 100], but in the majority of studies the prevalence was around 25%, although in one study it was only 4% [101]. Of these seven studies, three were case-control studies [97, 98, 101], two of which used healthy controls from the general population [97,101], and the third used healthy volunteers from among hospital staff [98]. Again results were conflicting, with one study suggesting a five-fold increase in lactose intolerance in IBS subjects compared to controls, one study showing no difference in prevalence between the two, and the third a more modest increase in prevalence in cases with IBS. The data to support the role of lactose hydrogen breath testing in IBS are therefore conflicting, and at present no recommendation for the routine exclusion of lactose intolerance can be made.

Role of testing for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in irritable bowel syndrome

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth has been proposed as a possible etiological factor in IBS. Lactulose and glucose hydrogen breath tests, and jejunal aspirate and culture, have been utilized in suspected IBS patients. Three studies have demonstrated a positive lactulose hydrogen breath test in 50-80% of patients with IBS defined according to the Rome I or II criteria [67,102,103], whilst the prevalence of a positive glucose hydrogen breath test has been reported to be between 30% and 40% in patients defined by Rome II criteria [66,104]. These studies have caused considerable interest, and as a result of their findings antibiotics, such as rifaximin, have been used for the treatment of IBS [68]. However, a Swedish case-control study has reported that the prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, following jejunal aspirate and culture, is no higher in subjects meeting the Rome II criteria for IBS than in healthy controls from the general population [105]. Only 7 (4%) of 162 IBS patients had a positive culture compared to 1 (4%) of 26 controls. These data are supported by a large case-control study conducted recently in the USA [106], in which the prevalence of a positive lactulose hydrogen breath test was equally high between IBS patients defined by Rome II criteria and healthy controls, suggesting that the high rates of positive breath testing may not be specific to individuals with IBS.

Role of blood tests in irritable bowel syndrome

Several studies have reported on the yield of certain blood tests in suspected IBS patients [83, 84, 87,107,108]. Two of these reported on the utility of a full blood count [83, 87], but only one patient had an organic explanation for their symptoms, biopsy-proven celiac disease, after applying the test. Five studies have utilized thyroid function tests in IBS [83, 84, 87, 107, 108]. When data from these studies are combined, 91 (4.2%) of 1860 IBS patients had abnormal thyroid function. One study performed C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate in 300 IBS patients, only three of whom had organic disease after applying the tests [87]. A panel of blood tests, often performed when patients with IBS are first seen in the outpatient clinic, therefore has a low yield in detecting organic disease in this situation. However, it would appear that the routine checking of thyroid function in subjects meeting diagnostic criteria for IBS is a reasonable strategy.

Role of stool examination

Two studies, which used the Rome I criteria and the International Congress definition of IBS [83, 84], tested stool for ova, cysts and parasites in over 1300 patients with suspected IBS. Of these, only 19 (1.4%) had a positive result. In one study none of the subjects meeting diagnostic criteria for IBS patients had a positive test.

Role of other abdominal investigations

Only one study has reported on the utility of abdominal ultrasound scan in 125 individuals with Rome I IBS [109]. Of these subjects, 22 (18%) had abnormal ultrasound findings, 6 (5%) of whom had gallstones. However, the detection of gallstones did not lead to a revision of the diagnosis of IBS in any of the included patients. One study used barium meal and follow-through in 114 patients meeting Rome I criteria for IBS [107]. Only one patient was found to have Crohn’s disease after investigation. These limited data do not support the routine use of either of these investigations in the diagnostic workup of patients with suspected IBS.

Summary

There remains some uncertainty surrounding the diagnosis of IBS for both the patient and clinician. Despite the fact that many physicians, particularly those in primary care, are either unaware of or do not use current recommended diagnostic criteria for IBS, there is no evidence that IBS can be reliably diagnosed using a physician’s opinion. Individual symptom items from the clinical history are unsatisfactory. Of the current symptom-based diagnostic criteria, the Manning criteria perform only modestly well overall, and less well in the two of the three prospective studies conducted since the original validation was performed. There are few data to support the use of the Rome I criteria, and no studies have validated the Rome II or III criteria, which is disappointing given that the latter are the current gold standard for the diagnosis of IBS. The best evidence appears to exist for the Kruis scoring system, although this system is probably too unwieldy for everyday use. Either further well-designed studies are required to validate current diagnostic criteria, or more accurate ways of diagnosing IBS without the need for investigation need to be developed.

In terms of investigating individuals with symptoms suggestive of IBS, there is limited evidence for a routine panel of blood tests, and more invasive investigations such as colonoscopy, breath testing, or barium studies appear to either have a very low yield, or have limited discriminatory value between IBS patients and normal individuals. In addition, the vast majority of studies have been conducted in secondary care settings, where the yield of organic disease is likely to be higher, and the findings should not be extrapolated to patients presenting to a primary care physician with symptoms suggestive of IBS. Current evidence does suggest, however, that screening all individuals with suspected IBS for thyroid dysfunction and celiac disease, with distal duodenal biopsy in those with positive serology, is a worthwhile strategy.

Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome

As IBS is a prevalent condition, with a chronic, relapsing and remitting course physicians need to have effective therapies available to them in order to drive down the costs of c onsultation and investigation in sufferers. Unfortunately, many of the traditional therapies, when studied in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), have shown variable efficacy in terms of their effect on resolution or cure of symptoms and follow-up in many cases has been limited to two or three months. In addition, newer agents such as the 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptor agonists and antagonists, which showed initial promise, have been withdrawn due to concerns over their safety profile, though some of these are now available on a restricted use basis. Data from individual RCTs of various therapies are conflicting in many cases, and systematic reviews and meta-analyses do not always produce consistent evidence of benefit [110–117]. However, recently a number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been completed as part of the update of the American College of Gastroenterology’s monograph on IBS [118], and have demonstrated some clinically useful results.

Efficacy of fiber in irritable bowel syndrome

Traditionally, patients with IBS were told to increase the amount of fiber in their diet, due to potentially beneficial effects on intestinal transit time [119]. However, evidence for any benefit on global IBS symptoms from individual placebo-controlled trials has been conflicting [120–123], although many of these studies are small and may have lacked sufficient power to detect a significant benefit, should one exist. Previous systematic reviews have also disagreed on whether fiber has any therapeutic effect [110, 114, 117], and current guidelines for the management of IBS make varying recommendations concerning the role of fiber [38–41]. The use of insoluble fiber, such as bran, is generally discouraged due to concerns that it may exacerbate symptoms, particularly pain and bloating.

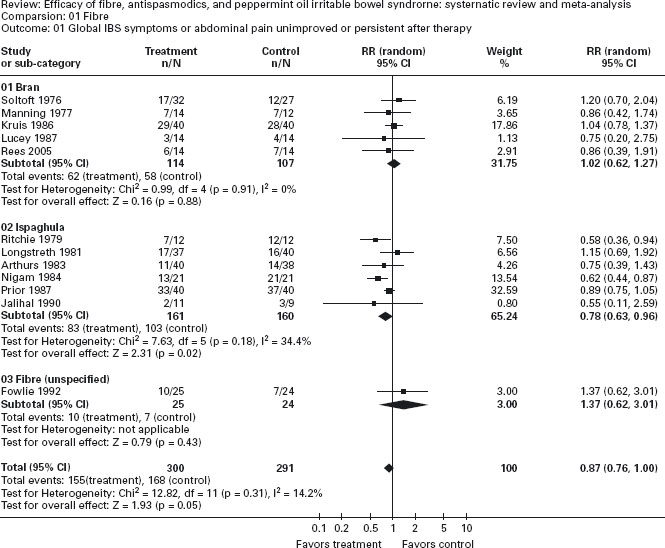

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis identified 12 placebo-controlled trials of fiber in IBS [124]. The main results of the meta analysis are shown in Figure 21.1. Overall, there appeared to be a modest benefit of fiber supplementation in IBS, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 11. However, this effect was limited to ispaghula, a soluble fiber, with a number needed to treat of 6. Insoluble fiber did not lead to any improvement in symptoms of IBS, though there was no convincing evidence that it worsened symptoms when data were pooled. Adverse events were very rare.

Unfortunately, the method of concealment of allocation was not reported in any of the trials, which may have led to an overestimation of the efficacy of fiber in IBS [125]. In addition, none of the trials adhered to the recommendations of the Rome committee for the design of trials of therapies for the functional GI disorders [126], most having been designed and conducted before these were published. Despite the methodological limitations of many of these RCTs, ispaghula is cheap and available over the counter, so it is probably a worthwhile first-line agent in patients with constipation-predominant IBS. A1c

Efficacy of antispasmodics and peppermint oil in irritable bowel syndrome

The pain, discomfort and altered bowel habit that IBS sufferers report may result from a combination of altered GI motility, smooth muscle spasm, visceral hypersensitivity and abnormalities of central pain processing [54, 56, 127]. Smooth muscle relaxants could therefore ameliorate some of the symptoms of IBS. Numerous antispasmodic agents have been studied, but the existing RCTs have produced disparate results [128–131]. Peppermint oil may also have antispasmodic properties [132]. In contrast to antispasmodics, the available RCT evidence for peppermint oil shows definite benefit [133–136].

A systematic review and meta-analysis identified 22 placebo-controlled trials of various antispasmodics in IBS [124], and demonstrated an overall benefit with active therapy, with NNT = 5 (Figure 21.2). There were significantly more adverse events in participants randomized to antispasmodics, though the majority consisted of dry mouth, dizziness, and blurred vision, and none were serious. When subgroup analyses were conducted according to the type of antispasmodic used, it became apparent that many of the antispasmodics that are most commonly used in clinical practice, such as mebeverine, alverine and dicycloverine had little or no evidence of efficacy in IBS. The best evidence, in terms of the number of patients studied, appeared to exist for otilonium (435 patients) and hyoscine (426 patients), with NNT = 5 and 4 respectively. A1a When data were pooled for the four RCTs of peppermint oil in a systematic review, there was evidence of a clear benefit, NNT = 3 (Figure 21.3) [124]. A1a Adverse events with peppermint oil were very rare, and not more frequent than were observed with placebo.

Again, the majority of these studies predated the Rome recommendations for RCTs of therapies for IBS [126], and none reported the method of concealment of allocation, so the number needed to treat may well be higher. The rationale for the efficacy of these drugs in IBS is speculative. Diarrhea-predominant IBS patients have a reduced colon diameter and accelerated small bowel transit on magnetic resonance imaging [137], so it may be that antispasmodics have their beneficial action via a combination of reduced colonic contraction and transit time, which may in turn lead to reduced pain and stool frequency. Peppermint oil has been shown to have antagonistic effects on the calcium channel [132], and may bring about smooth muscle relaxation, and therefore reduced contractility and pain.

Figure 21.1 Forest plot of randomized controlled trials of fiber versus placebo or low fiber diet in irritable bowel syndrome. Ford AC, Talley NJ, Spiegel BMR et al. Effect of fiber, antispasmodics, and peppermint oil in irritable bowel syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br Med J 2008; 337: a2313.

As with ispaghula, antispasmodics and peppermint oil are cheap, and the latter is available over the counter. These therapies should probably be used as first-line interven-tions for diarrhea-predominant IBS, although most of the trials predated the creation of these diagnostic subgroups, eliminating the possibility of analysis according to predominant stool pattern. A1a These agents may also benefit individuals whose predominant symptoms are either pain or bloating. Of the available antispasmodics, the strongest evidence base exists for hyoscine.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree