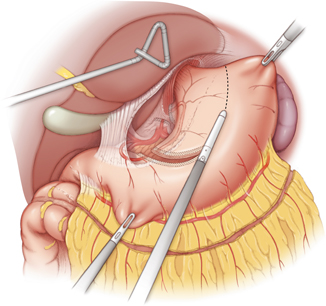

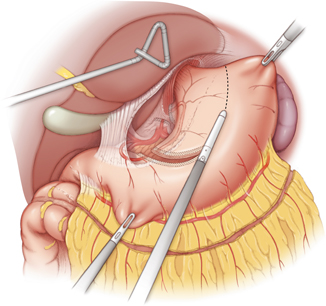

Fig. 10.1

The gastro-colic ligament is divided with a ligasure device along the greater curvature of the stomach. The right gastroepiploic arteriovenous arcade should be preserved during the dissection. Injury to the gastroepiploic arteriovenous arcade would result in immediate gastric conduit ischemia

1.

The right gastroepiploic artery is the main arterial blood supply to the gastric conduit and should be preserved in every case. The gastoepiploic vein is equally important and any direct manipulation of the gastroepiploic vascular arcade should be avoided. The adequacy of arterial blood flow within the artery can be tested with a Doppler probe intraoperatively if there are concerns about an injury to the arcade.

2.

The intraoperative surgical margins on the gastric conduit should be assessed prior to the esophagogastric anastomosis. This can be a particular challenge for large GE (gastrointestinal junction) junction tumors that extend into the gastric fundus. The gastric conduit should not be narrower than 4 cm in diameter.

3.

The gastric fundus should be maintained in order to provide adequate length of the gastric conduit. This principle becomes very important when the esophagogastric anastomosis needs to be performed in the cervical neck, where adequate length of the gastric conduit is essential to avoid tension on the anastomosis.

4.

The shape and diameter of the conduit is an important consideration in terms of gastric emptying. The conduit should ideally be 4–5 cm in diameter. Large and patulous gastric conduits may not empty well, which results in delayed gastric emptying. Large and dilated gastric conduits may result in venous congestion and may possibly contribute to conduit ischemia.

The preservation of the right gastroepiploic ateriovenous arcade is sufficient to sustain the gastric conduit after mobilization [2]. The left and right gastric artery arcades can be routinely divided without increased risk for ischemia because approximately 60 % of the blood supply comes from the right gastroepiploic arteriovenous arcade [3]. The ideal width of the gastric conduit should be 4–5 cm in diameter. The gastric conduit is created by dividing the mobilized stomach along the lesser curvature with a linear endo-mechanical stapler (See Fig. 10.2). Gastric conduits that are too narrow can result in gastric tip necrosis due to the poor collateral circulation in the submucosa of the gastric fundus [4]. The gastric conduit is typically passed through the esophageal hiatus and the intrathoracic anastomosis is performed at the level of the azygous vein. The esophageal hiatus should be widened enough to avoid compression of the esophageal conduit and subsequent venous stasis.

Fig. 10.2

The gastric conduit is created by dividing the stomach along the greater curvature with a linear endo-mechanical stapler. A tubular gastric conduit is created, which should measure 4–5 cm in diameter for maximal conduit perfusion and functional emptying

The incidence of gastric conduit ischemia and necrosis depends largely on the technique that was used to mobilize the stomach. The occurrence of an anastomotic leak and/or stricture is largely related to the incidence of ischemia of the gastric conduit. The incidence of anastomotic complications varies in the reported studies with a range of 0–24 % [5–8]. Kassis et al. recently reported an overall anastomotic leak rate of 12.3 % for cervical anastomoses and 9.3 % for intrathoracic anastomosis in a large series of 7595 esophageal resections from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database [9]. Orringer et al. reported a large series of 1085 transhiatal esphagectomies, which reported an anastomotic leak rate of 13 % and a gastric conduit necrosis rate of 2.6 % [10]. The higher rate of gastric conduit ischemia/necrosis encountered with the cervical esophagogastric anastomosis is thought to be related to the possible compression from the mediastinum and/or the thoracic inlet. The overall incidence of gastric conduit necrosis ranges from 0.5 to 10.4 % [10–15]. The reported series are summarized in Table 10.1.

Table 10.1

Esophagectomy series reporting the incidence of esophageal conduit necrosis

Series | # Patients | Mortality (%) | Anastomosis leak (%) | Conduit ischemia (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Orringer [10] | 1085 | 4 | 13 | 2.6 |

Peracchia [11] | 242 | 0.8 | 5.8 | 1.2 |

Davis [12] | 959 | 10.6 | 3.9 | 0.5 |

Shuchert [13] | 222 | 1.4 | – | 3.2 |

Briel [14] | 230 | 3.5 | 14.3 | 10.4 |

Moorehead [15] | 760 | 3.8 | – | 1.0 |

The predisposing factors for gastric conduit necrosis include direct injury to the gastroepiploic ateriovenous arcade, external compression of the gastric conduit, low perioperative blood pressure, and excessive manipulation of the gastric conduit. The risk of gastric conduit necrosis can be minimized with meticulous operative technique for mobilization of the stomach and creation of the gastric tube. The gastroepiploic arcade should be identified intraoperatively with gentle palpation or by Doppler probing. The localization of the primary blood supply to the gastric conduit should minimize the risk of direct injury. In addition, the author recommends checking for twisting of the gastric conduit prior to the anastomosis and ensuring that the esophageal hiatus is not compressing the gastric conduit.

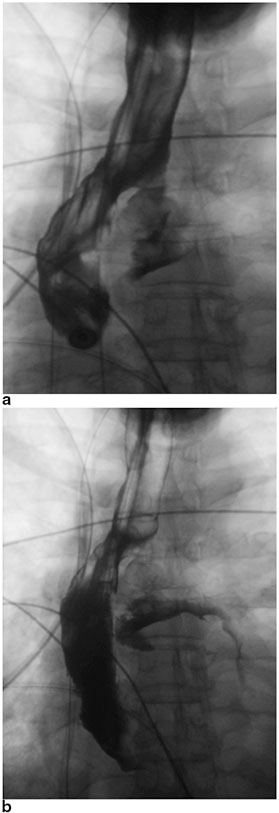

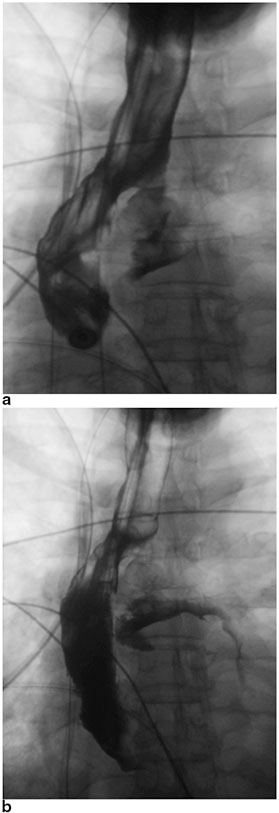

Diagnosis of Gastric Conduit Ischemia

The early recognition and diagnosis of gastric conduit necrosis is critical to minimizing the risk of perioperative mortality. The clinical signs and symptoms of gastric conduit necrosis depend on the degree of ischemia and the extent of the esophagogastric leak. Patients often develop tachycardia, leukocytosis, metabolic acidosis, and altered mental status. The patients can potentially develop florid sepsis and respiratory failure requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission, mechanical ventilation, and vasopressor support. The contrast esophagogram should demonstrate extravasation of the contrast consistent with an anastomotic leak (See Fig. 10.3a, b). An upper endoscopy can be performed with minimal insufflation to assess the esophagogastric anastomosis and the mucosa of the gastric conduit can be evaluated for ischemia or frank necrosis. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax can also be obtained to evaluate for the evidence of an anastomotic leak, such as pneumomediastinum, pleural effusion, or disruption of the esophagogastric anastomosis. For patients with cervical anastomoses, the neck incision can be opened directly to inspect for drainage from the anastomosis and assess the fundus for ischemia or necrosis.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree