Interpretation of Colonic Biopsies

The ability to endoscopically visualize the entire mucosal surface of the large bowel and to biopsy or cytologically sample normal- and abnormal-appearing areas allows clinicians to diagnose and manage colorectal diseases. Biopsies yield information concerning disease patterns, distribution, extent and/or severity, acuity versus chronicity, clinical state of remission or relapse, and complications. In one study, interpretation of mucosal biopsies yielded a positive diagnosis in 31% of patients with chronic diarrhea who did not have a definitive diagnosis prior to the biopsy (85). The most common diagnoses were IBD and microscopic colitis, although cases of ischemia and infection were also first diagnosed on the biopsy (85).

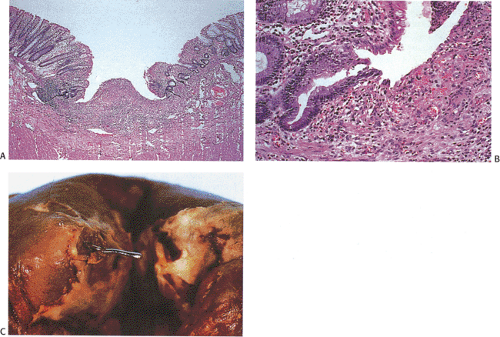

Optimal biopsy evaluation can only occur when careful consideration is given to the clinical, historical, endoscopic, radiographic, microbiologic, and other available patient data. Once tissue has been removed, it may be cultured, examined histologically or ultrastructurally, or submitted for biochemical analysis. Not only can it be examined in routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) sections, but it may also be submitted to a battery of histochemical and immunocytochemical stains as well as molecular biologic techniques, many of which can be performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded materials. One may also re-embed colonic biopsies in which there is a discrepancy between the clinical impression and the histologic findings. In so doing new diagnoses can be made in up to 31% of biopsies (86). In our opinion, this is not likely to be cost effective, especially since in most cases the new diagnosis was that of a small hyperplastic polyp (86), a lesion of little clinical consequence.

One of the most common uses of the colorectal biopsy is to determine the etiology of a colitis or proctitis, which may share overlapping clinical, radiologic, or pathologic features with other disorders (Table 13.2). In the best of circumstances, analysis of the biopsy specimen, in conjunction with an interpretation of the clinical data (Table 13.3), will yield a definitive diagnosis. More often, however, the biopsy does not provide a specific diagnosis, but rather narrows down the differential diagnosis. The histologic features may suggest an inflammatory condition and provide knowledge concerning the severity of the underlying lesion or the extent of disease, allowing one to correlate the clinical impression with the histologic findings. One may also be able to diagnose the presence of specific neoplasms or the presence of a treatable organism.

Mucosal biopsy interpretation can be difficult due to normal architectural variants, effects of the biopsy procedure, and lack of knowledge of the dynamic mucosal events accompanying mucosal repair. Some of the mucosa features that are often unappreciated are the following:

Crypt branching is normal in the area of the innominate groves.

There is normally a mononuclear cell infiltrate in the upper mucosa that is sometimes referred to as a physiologic infiltrate. It is densest in the cecum (a site of bacterial stasis) and least in the rectum. The crypts are normal (87).

In general, the lamina propria cellularity is greatest in the cecum and ascending colon and it decreases distally.

Mild crypt irregularity in the rectum is not considered to be clinically significant.

While there are normally five intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 colonocytes, the number is increased in the cecum (perhaps secondary to the stasis that occurs there) and there are abundant intraepithelial lymphocytes in the epithelium overlying lymphoid follicles.

A previously inflamed bowel may return to a histologically normal appearance. This is especially important in evaluating biopsies from patients with ulcerative colitis.

It is important to examine mucosal biopsies in a standardized way in order to determine that they are abnormal and to establish a probable diagnosis. A systemic analysis should include evaluation of the features listed in Table 13.4. The most common pattern one sees when evaluating a biopsy for colitis are diffuse and focal active colitis or proctitis without other specific features. The pathology report should indicate whether features are acute, chronic, or chronic active and whether the changes are focal or diffuse. Specific features such as the presence of microorganisms, granulomas, or abnormal infiltrates should be noted. An attempt should be made to establish the etiology of the changes since “diagnoses” such as nonspecific colitis are of little help to the

clinicians who already know that the patient has some form of colitis.

clinicians who already know that the patient has some form of colitis.

TABLE 13.2 Differential Diagnosis of Colitis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 13.3 Information That Aids Pathologists Interpreting Colorectal Biopsies | |

|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree