Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) refers to the idiopathic inflammatory bowel disorders, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and microscopic or lymphocytic and collagenous colitis. Clearly, a number of other conditions also are associated with inflammation, including bacterial and parasitic infections, ischemic bowel disease, and radiation colitis. Nevertheless, until the causes of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are identified, the term inflammatory bowel disease serves a useful purpose in distinguishing these conditions from other bowel disorders.

IBD has a prevalence of 0.3% to 0.5% in the adult U.S. population with a slight female preponderance. It is most commonly seen in young patients between the ages of 15 and 25; however, there is second peak in the incidence of IBD at 40 to 60 years. Approximately 15% of patients with IBD have close relatives who also have IBD.

I. DISTINGUISHING FEATURES OF ULCERATIVE COLITIS (UC) VERSUS CROHN’S DISEASE

(Table 37-1).

Ulcerative colitis is an inflammatory disorder of the mucosa of the rectum and colon. The rectum is virtually always involved, and if any portion of the remaining colon is involved, it is in a contiguous manner extending proximally from the rectum. On the other hand, Crohn’s disease typically affects all layers of the bowel wall and may do so usually in a patchy distribution throughout the entire gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Crohn’s disease may involve any part of the GI tract from the mouth to the anus, most frequently involves the terminal ileum. Approximately one third of cases involve the small bowel only, one third involve the colon only, and one third involve both the colon and the small bowel. The rectum may be spared. Crohn’s disease in the elderly usually involves only the colon. Crohn’s disease of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum is rare, but may present alone or in combination with involvement of the other segments of the GI tract.

Patients with Crohn’s disease may have predominantly inflammatory, obstructive, or perianal disease. Chronic inflammation leads to fibrosis and strictures. Fistulas may connect the diseased bowel with another bowel loop (enteroenteric), the bladder (enterovesical), vagina, or skin (enterocutaneous). The presentation of Crohn’s disease varies with the site and degree of involvement. It may be gradual in onset or may present with recurrent episodes of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and/or low-grade fever. Physical examination may reveal a right lower quadrant mass or tenderness, anal fissures, perianal abscess, or fistulas. Some 10% to 15% of patients with either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease have extraintestinal manifestations of the disease (

Table 37-2).

In most patients, the two disorders can be distinguished on clinical, radiologic, and pathologic grounds. However, in about 20% of patients with IBD affecting the colon, it is impossible to make a definitive diagnosis (indeterminate colitis).

II. ETIOLOGY.

Because the causes of IBD are not known, the pathophysiology of the disorders is incompletely understood. An immunologic mechanism in the pathogenesis is assumed, but the inciting causes are incompletely understood. The intestinal flora, various cytokines including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and some of the interleukins, and other factors are thought to play a role in the ongoing inflammatory process.

Hereditary factors appear to play a role; patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease have a 10% to 15% chance of having a first- or second-degree relative who also has one or the other type of IBD.

III. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS.

A variety of conditions can cause intestinal inflammation and present with signs and symptoms similar to those of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. These conditions are summarized in

Table 37-3.

The bacterial and parasitic colitides must be considered in all patients with new-onset bloody diarrhea and rectal or colonic mucosal inflammation; also, some infections are associated with exacerbations of known idiopathic IBD. Thus, stool examinations for ova and parasites, bacterial pathogens, and Clostridium difficile toxin is indicated. Eosinophilic colitis-enteritis is a variation of IBD of unknown etiology. It may represent an allergic reaction of the mucosa to allergen.

Ischemic colitis, which may occur in patients with cardiac arrhythmias or cardiovascular disease, or individuals taking estrogen, birth control pills, or estrogen agonists (SERMs), can be confused with IBD, particularly Crohn’s disease, because of its segmental distribution and tendency to produce strictures.

Radiation bowel injury may involve any portion of the GI tract but typically affects the rectum or sigmoid colon in patients who have received pelvic irradiation. Acute radiation injury occurs during or shortly after the radiation treatment, but chronic radiation colitis, which is a form of ischemic bowel disease, may occur months to years later.

Because lymphoma, Yersinia enterocolitis, and tuberculosis often involve the distal small intestine and the cecum, they may be confused with Crohn’s disease. The diagnosis of lymphoma may be made by biopsy of enlarged lymph glands or other involved organs. Sometimes laparotomy is necessary. Y. enterocolitis can be diagnosed by stool cultures or serologic tests. Enteric tuberculosis is rare in the United States but should be suspected in patients from areas of the world in which the disease is endemic.

IV. CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A. History

1. Signs and symptoms.

Patients with ulcerative colitis typically complain of bloody stool. If the inflammation is confined to the rectum, stools may be formed. Patients may even present with constipation. More extensive involvement of the colon is associated with bloody diarrhea caused by the diminution in absorption of water, electrolytes, and oxidation by the affected mucosa. Crampy lower abdominal pain is temporarily relieved by bowel movements.

Patients with Crohn’s disease usually have a history of additional chronic signs and symptoms, such as fatigue, weight loss, and persistent abdominal pain, often in the right lower quadrant. Blood in the stool occurs if there is colonic involvement. Stools are often formed but may be loose if there is extensive involvement of the colon or if there is disease of the terminal ileum. The latter causes diarrhea because of the malabsorption of bile salts and the consequent inhibition of water and electrolyte absorption in the colon. Bile acid malabsorption also may reduce the bile acid pool, which leads not only to fat malabsorption but also to supersaturation of cholesterol in bile in the gallbladder and risk of development of cholesterol gallstones. The fat malabsorption also predisposes to oxalate renal stones. The inflammatory nature of Crohn’s disease can be responsible for several complications outside the bowel, including hydronephrosis due to ureteral obstruction and pneumaturia secondary to an enterovesical fistula.

2. Onset and course of symptoms.

Both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis typically begin in childhood or early adulthood, although ulcerative colitis may develop in patients of any age; a second peak in incidence of Crohn’s disease occurs in the elderly, in whom the illness can be confused with ischemic bowel

disease. Most patients with ulcerative colitis experience intermittent exacerbations with nearly complete remissions between attacks.

In ulcerative colitis, about 5% to 10% of patients have one attack without subsequent symptoms for decades. A similar number have continuous symptoms, and some have a fulminating course requiring total proctocolectomy. Patients with Crohn’s disease generally have recurrent symptoms of varying frequency.

3. Growth retardation and failure to develop sexual maturity

are common in children and adolescents with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. In fact, these complications may be the primary reason for the patient to consult a physician. Growth failure is rarely caused by endocrine abnormalities but rather is a consequence of reduced caloric and nutritional intake or utilization. Treatment of the ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, with attention to good nutrition, usually results in reestablishment of normal growth and development.

B. Physical examination.

Patients with IBD often are thin and undernourished. Pallor due to anemia of blood loss or chronic disease may be evident. Tachycardia may result from dehydration and diminished blood volume, and a low-grade fever may be present. Mild-to-moderate abdominal tenderness is characteristic of ulcerative colitis. A tender mass in the right lower quadrant is typical of Crohn’s disease. The rectal examination in patients with ulcerative colitis reveals bloody stool or frank blood, whereas in Crohn’s disease, perianal scarring or fistulas may be identified. Abdominal distention, rebound tenderness, absence of bowel sounds, and high fever suggest toxic megacolon or abscess (see

section VII.A). Extraintestinal manifestations of IBD may be evident (

Table 37-2).

V. DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES.

IBD is diagnosed based on integration of clinical, endoscopic, histopathologic, radiologic, and other imaging data.

A. Laboratory studies.

A complete blood count (CBC), urinalysis, and serum chemistry tests are appropriate during the initial evaluation of a patient with suspected IBD.

Serologic examination of blood for specific antibodies, such as ANCA, is recommended. Several different serologic markers for IBD have been identified, including perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCA), antibodies to Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ASCA), pancreatic antibodies (PAB), antibodies to the outer membrane Porin C of Escherichia coli (anti-Omp C), antibodies to a DNA sequence from Pseudomonas Fluorescens (anti-12) and anti-C B 1 flagellin.

These antibodies are not sufficiently sensitive to be used to screen for IBD in the general population. However, they may be helpful for predicting the phenotype of IBD. The finding of ASCA+/pANCA− predicted Crohn’s disease in 80% to 95%, the finding of pANCA+/ASCA− predicted ulcerative colitis in about 90% of patients tested. Several studies suggest that Crohn’s disease patients with more positive serologies and higher titers are more likely to have complications such as strictures, fistulae, perforations, and requirement for surgery.

Several commercial laboratories offer “panels” of the serologic markers using computerized recognition patterns to distinguish subtypes of IBD (CD vs. UC).

B. Examination of the stool.

Stool from patients suspected of having ulcerative colitis should be examined for leukocytes and ova and parasites, cultured for bacterial pathogens including Escherichia coli O157:47, Campylobacter jejuni, and Yersinia enterocolitica and tested for C. difficile toxin titer.

1. Fecal leukocytes

are common to most inflammatory conditions of the colon but are not common in irritable bowel syndrome or noncolonic diarrhea.

2.

Examination for ova and parasites may establish the diagnosis of amebiasis, although the sensitivity of stool examination for amebae is lower than 40%. The serum indirect hemagglutination and gel diffusion precipitant tests are more than 90% sensitive for amebic infection. It is particularly important to obtain several fresh stool samples for examination of ova and parasites before barium-contrast studies are performed because the presence of barium in the GI tract can obscure ova and parasites for a week or more.

3. Bacterial pathogens

may be identified by stool culture. Of particular interest is

Campylobacter jejuni ileocolitis, which may present with acute, colicky lower

abdominal pain, fever, bloody diarrhea with mucus, and many of the endoscopic, radiologic, and histologic features of ulcerative colitis. The disease typically subsides within several days but may run a protracted course, in which case treatment with erythromycin or ciprofluxin may provide relief of symptoms.

Another pathogen that may complicate the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis is C. difficile, the bacterial agent that has been implicated in antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. C. difficile may be relevant to ulcerative colitis in two ways. First, antibiotic-associated colitis may be confused with ulcerative colitis. Second, C. difficile may be responsible for exacerbations of preexisting ulcerative colitis. When chronic ulcerative colitis is in remission, the demonstration of C. difficile toxin in the stool is probably related to recent treatment with sulfasalazine or antibiotics. Colonic infection with enteroinvasive E. coli, especially E. coli O157:H7, may resemble ulcerative colitis and present with similar findings.

C. Flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy

is indicated in the evaluation of rectal bleeding of any cause. The normal rectal and colonic mucosa appears pink and glistening. When the bowel is distended by insufflated air, the submucosal vessels can be seen. Normally, there is no bleeding when the mucosa is stroked with a cotton swab or touched gently with the tip of the sigmoidoscope.

In ulcerative colitis, the mucosal surface becomes irregular and granular. The mucosa is friable, meaning that it bleeds easily when touched. With more severe inflammation, bleeding may be spontaneous. These findings are nonspecific and may be seen in most of the conditions listed in

Table 37-3. In some patients with chronic ulcerative colitis, pseudopolyps develop. The rectal mucosa is normal in patients who have Crohn’s disease without rectal involvement. If the disease does affect the rectum, the appearance may be similar to that of ulcerative colitis or may include aphthous, deep or linear ulcerations and fissures.

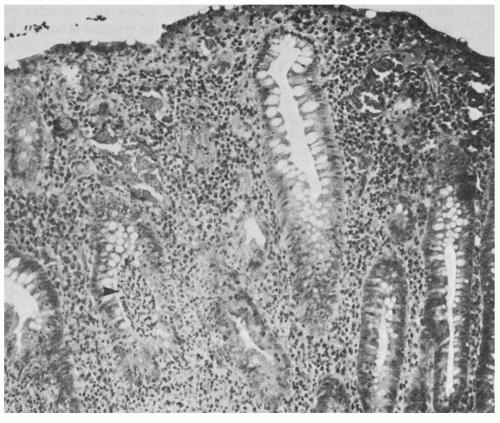

D. Mucosal biopsy.

Sigmoidoscopic or colonoscopic mucosal biopsies in patients with IBD generally are safe; however, they should not be performed if toxic megacolon is suspected. In ulcerative colitis, the histopathology of the rectal mucosa may show a range of abnormal findings. These include infiltration of the mucosa with inflammatory cells, flattening of the surface epithelial cells, a decrease in goblet cells, thinning of the mucosa, branching of crypts, and crypt abscesses (

Fig. 37-1). All of these findings, including crypt abscesses, are nonspecific and may be seen in other colitides, including Crohn’s disease, bacterial colitis, and amebiasis. Because endoscopic biopsies include mucosa and a variable proportion of submucosa, the transmural nature of Crohn’s disease cannot be appreciated. However, substantial submucosal inflammation or fissuring of the mucosa may suggest Crohn’s disease. The finding of noncaseating granulomas also strongly favors a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease (

Fig. 37-2), but granulomas are identified infrequently in mucosal biopsies from patients with established Crohn’s disease and may accompany other conditions, such as tuberculosis and lymphogranuloma venereum. The identification of amebic trophozoites by biopsy confirms that diagnosis. Large numbers of mucosal eosinophils are typical of eosinophilic colitis.

E. Radiography

1.

The plain film of the abdomen usually is normal in patients with mild-to-moderate IBD. Air in the colon may provide sufficient contrast to indicate loss of haustral markings and shortening of the bowel in ulcerative colitis or narrowing of the bowel lumen in Crohn’s disease.

In severe colitis of any cause, the transverse colon may become dilated (

Fig. 37-3). When this finding is accompanied by fever, elevated white cell count, and abdominal tenderness, toxic megacolon is likely (see

section VII.A). The plain film of the abdomen should be repeated once or twice a day in patients with toxic megacolon to follow the course of colonic dilatation.