15 Inflammatory bowel disease

Case

A 28-year-old female presents with a 3-month history of diarrhoea, weight loss, fatigue, and right lower quadrant abdominal pain. She complains of six to eight non-bloody bowel movements daily with at least one at night that awakens her from sleep. She has lost 10 kg since her symptom onset. She has fevers to 38.5°C without chills. She also complains of perianal pain with purulent drainage. She has generalised joint aches with intermittent swelling of the knees and mouth sores. Her past medical history is otherwise unremarkable and she does not take any medications. She denies taking any non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. She is an active smoker of one pack a day for the last 5 years. She has no family history of inflammatory bowel disease.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is traditionally divided into ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). Unlike infectious colitis that is typically self-limited, IBD is a chronic illness that is punctuated by disease exacerbations and remissions. While some similarities exist, UC and CD are very different diseases with regard to their clinical presentation, pattern of bowel involvement, response to therapy and prognosis (Table 15.1 and Box 15.1). With current methods, proper diagnosis of CD or UC can be made, although 10–15% of patients are labelled indeterminate colitis. Incidence and prevalence rates for UC and CD vary throughout the world but are highest in developed countries of northern Europe and North America.

Table 15.1 Pathological features in inflammatory bowel disease

| Ulcerative colitis | Crohn’s disease |

|---|---|

| Distribution | |

| Macroscopic appearance | |

| Microscopic appearance | |

∗ Preservation of crypt architecture suggests acute self-limited colitis.

† Granulomas may occur in tuberculosis, schistosomiasis and syphilis.

Ulcerative Colitis

Clinical presentation

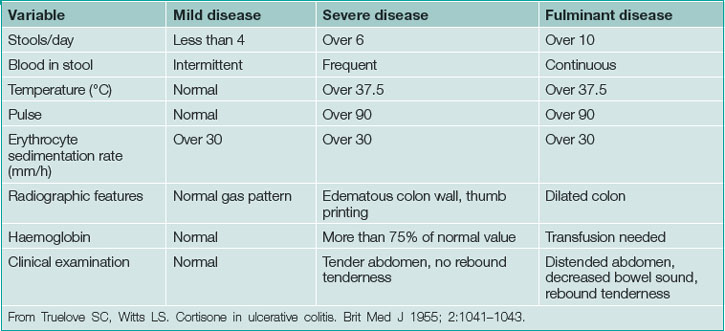

UC typically presents in the third or fourth decade of life. Clinical presentation is based on disease location and severity. Severity is classified as mild, severe or fulminant with moderate disease between mild and severe (Table 15.2). Diarrhoea, usually bloody with cramping typically awakening the patient from sleep, signifies mucosal inflammation. Mild disease may be accompanied by frequent diarrhoea but is not associated with significant life impairment. Moderate disease, between mild and severe, typically leads to significant symptoms including profound diarrhoea (usually bloody), dehydration, fatigue and weight loss. This may progress to severe disease, which may require hospitalisation. Fulminant disease is most severe often requiring intensive care or surgery.

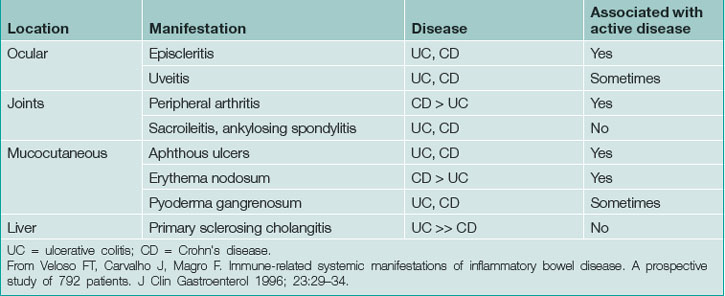

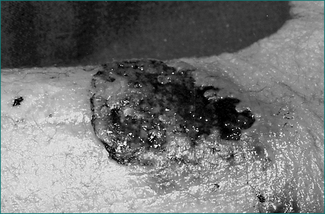

UC may be associated with extraintestinal manifestations in some patients (Table 15.3) which may be associated with disease activity (Fig 15.1). Those not associated with disease activity may run a clinical course independent of the disease and persist after colectomy.

Disease extent and location

Frequent low-volume bowel movements, urgency, rectal bleeding and tenesmus alone suggest proctitis. However, patients with or without these symptoms may also present with prostration, fever, tachycardia, dehydration and complications of blood loss, suggesting more severe disease or more extensive bowel involvement. Advanced cases may present with massive abdominal distention because of megacolon. In fulminant colitis, severe diarrhoea and high C-reactive protein despite intensive treatment predict eventual colectomy. Fortunately, the presentation of fulminant colitis is relatively uncommon.

Diagnosis

Among patients without a prior history of ulcerative colitis, presenting features are non-specific so that additional diagnostic testing is required. Diagnosis is confirmed by clinical features, endoscopic and histological findings as well as stool examination to exclude acute colitis. Infection, ischaemia, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication-induced colitis, diverticular colitis and Crohn’s disease are important considerations.

Radiology

Plain abdominal x-rays should be performed to exclude toxic megacolon and perforation among severely ill patients. Computed tomography (CT) scanning may be considered if there is concern of other aetiologies such as Crohn’s disease. CT of the abdomen may reveal colonic thickening and provide additional information as to the extent of the disease. Barium enema is rarely performed because of the widespread use of sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy (Fig 15.2).

Sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy and biopsy

Endoscopic visualisation with biopsy is essential for all patients with suspected UC and is often necessary to document disease activity for a suspected flare. Disease activity, if present, should be visible in the rectum and may extend more proximally. Rectal sparing or segmental colitis raises the possibility of infection, ischaemia, Crohn’s disease or other aetiology. Biopsies confirm the presence of chronic colitis and exclude acute colitis as seen with infection. Among patients with colitis refractory to therapy, especially if they are receiving corticosteroid or immunosuppressive therapy, cytomegalovirus should be excluded by biopsy with special studies. Severely ill patients may undergo an unprepped flexible sigmoidoscopy whereas patients with mild to moderate disease are often prepped for colonoscopy. There is usually little value in performing a complete colonoscopy on patients with active UC and it may be dangerous. However, prepping for colonoscopy, if possible, will allow for better visualisation above the sigmoid colon, especially if findings are not typical for UC or it is important to determine extent of disease for therapy. Flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsy is often sufficient for those with established disease to confirm disease activity. Among patients with long-standing quiescent disease proximal to the rectum, colonoscopy with biopsies is routinely performed for dysplasia surveillance.

Mild to moderate disease

Oral mesalamine

The best option for patients with mild to moderate UC is mesalamine (5-aminosalicylate), orally or rectally. Response rates vary because of differences in dose, disease activity and definitions of outcomes but about two-thirds will respond. Sulfasalazine, the first of this class, is both an inexpensive and effective medication. It remains essentially unchanged until it reaches the colon where it is cleaved into the active moiety 5-aminosalicylate and sulfapyridine by bacteria. Sulfapyridine (a sulfa antibiotic) is responsible for most of the observed toxicity that includes allergic reaction or renal toxicity (Box 15.2). The remaining mesalamine formulations differ on their mechanism and site of drug delivery. Newer preparations release in the colon, require fewer tablets and can be dosed once or twice daily to improve compliance. These medications are well tolerated. Headache is the most common adverse effect and, rarely, renal toxicity occurs. A baseline serum creatinine should be determined prior to starting therapy. Pancreatitis has also been described with sulfasalazine due to its sulfa moiety but also with mesalamine, although the likelihood with mesalamine is extremely low.

Box 15.2 Side effects of sulfasalazine∗

∗ Start at one 500 mg table, twice daily on the first day after meals, then increase by two tablets every second day until the patient is taking the full amount (typically, 1 g four times a day in acute disease; and 1 g twice a day for prophylaxis). Usually efficacious within 2–4 weeks (in 40–80% of patients) A blood count and urinalysis should be performed before starting therapy and then regularly during the first 3 months of treatment, and thereafter every 6 months. Supplement with folate, 1 mg/day orally. The drug may also be of specific benefit for the arthropathy in ankylosis spondylitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

Mesalamine is not useful in moderate to severe UC and in mild to moderate disease is often administered at too low a dose. In appropriate doses all are probably equally effective. Sulfasalazine is relatively inexpensive and once or twice daily preparations will enhance compliance. Olsalazine should be avoided if possible, because it can cause secretory diarrhoea. Common preparations with the usual doses to induce and maintain remission are outlined in Table 15.4.

Table 15.4 Oral mesalamine preparations for induction and maintenance of remission in mild to moderate ulcerative colitis

| Optimal daily dose for remission (g) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Drug | Induction | Maintenance |

| Oral mesalamine | ||

| Sulfasalazine | 4–6 | 2–4 |

| Eudragit S coated | 3.6–4.8 | 2.4–3.6 |

| Ethylcellulose coated | 3–4 | 2–3 |

| Balsalazide | 6.75 | 3–4.5 |

| Topical mesalamine | ||

| Mesalamine suppository | 0.5–1 twice daily | 1 daily |

| Mesalamine enema | 4 nightly | 4 nightly or every other night |

From Kornbluth A, Sachar DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105:501–523.